Connecting Science to Practice

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a type of blood cancer that carries

a high risk for developing venous thromboembolism

(VTE). Although most data support using aspirin, warfarin,

or an injectable blood thinner to lower the risk for VTE in

patients with MM, limited data suggest an oral blood thinner

may also be safe and effective. We reviewed 106 newly

diagnosed patients with MM who were prophylactically prescribed

the oral blood thinners apixaban or rivaroxaban

while undergoing induction treatment, and we found a VTE

rate of 4% and a bleeding rate of 5%. Our study suggests

that oral anticoagulants may be effective and safe at preventing

VTE in patients with MM, but more data are needed to

confirm this finding.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma-cell malignancy associated with a high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) because of disease-, patient-, and treatment-related factors, such as the use of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs).1,2 Trials investigating the use of the IMiDs thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide in patients with MM showed rates of VTE of up to 12%.3,4 Studies also show that the risk for VTE is highest within the first 6 months of induction therapy in patients newly diagnosed with MM.5,6

As a result of the negative short- and long-term consequences of a VTE event and the high incidence of VTE in the MM population,7 thromboprophylaxis with an anticoagulant is strongly recommended for patients who have an intermediate or high VTE risk by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) treatment guidelines.8 High risk is defined via the IMPEDE VTE and SAVED risk assessment models as an IMPEDE VTE score of ≥8 points or a SAVED score of ≥2 points, whereas intermediate risk is defined as an IMPEDE VTE score of 4 to 7 points.9,10 VTE risk and protective factors as well as risk classifications within the IMPEDE VTE and SAVED scores are shown in Table 1.9,10 Similarly, the 2008 International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) guidelines recommend tailoring anticoagulant prophylaxis according to VTE risk factors such as use of lenalidomide with high-dose dexamethasone (doses >480 mg per month).7 IMWG guidelines also suggest that patients with ≥2 risk factors should receive prophylactic anticoagulation with low-molecular–weight heparin or warfarin.7

Most patients newly diagnosed with MM are classified as having an intermediate VTE risk and qualify for thromboprophylaxis via the IMPEDE VTE score if they lack any protective factor.9 Although concordant on the need for thromboprophylaxis for most patients newly diagnosed with MM, the IMWG and the NCCN guidelines lack a preference for which anticoagulant to choose.7,8 The IMWG and NCCN guidelines recommend that intermediate- to high-risk patients receive prophylactic doses of enoxaparin or therapeutic warfarin doses targeting an international normalized ratio of 2 to 3.7,8 However, the NCCN guidelines offer additional anticoagulant options with fondaparinux and the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) apixaban and rivaroxaban.8 Low-dose aspirin is only recommended for patients with a low risk for VTE according to both guidelines.7,8

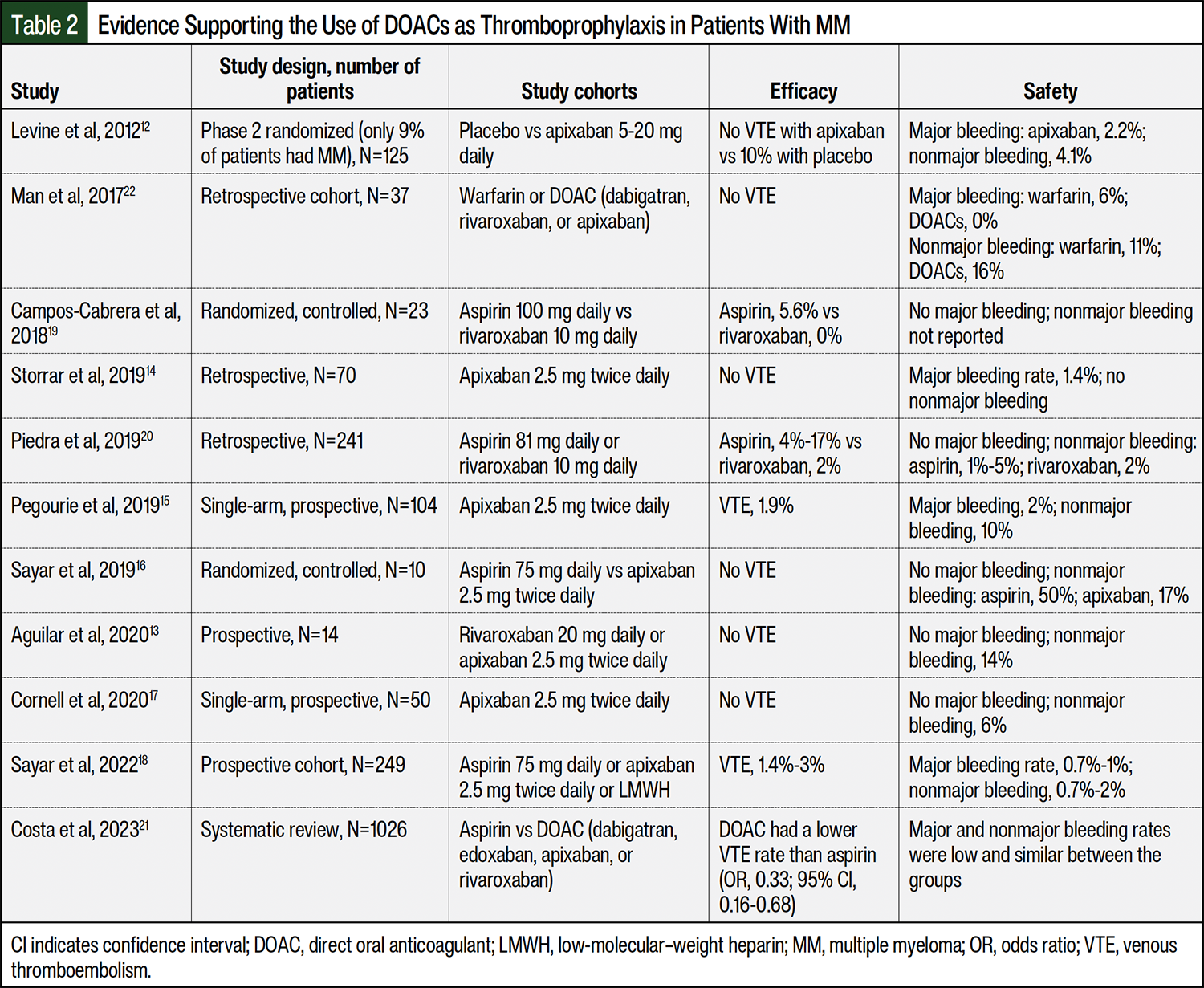

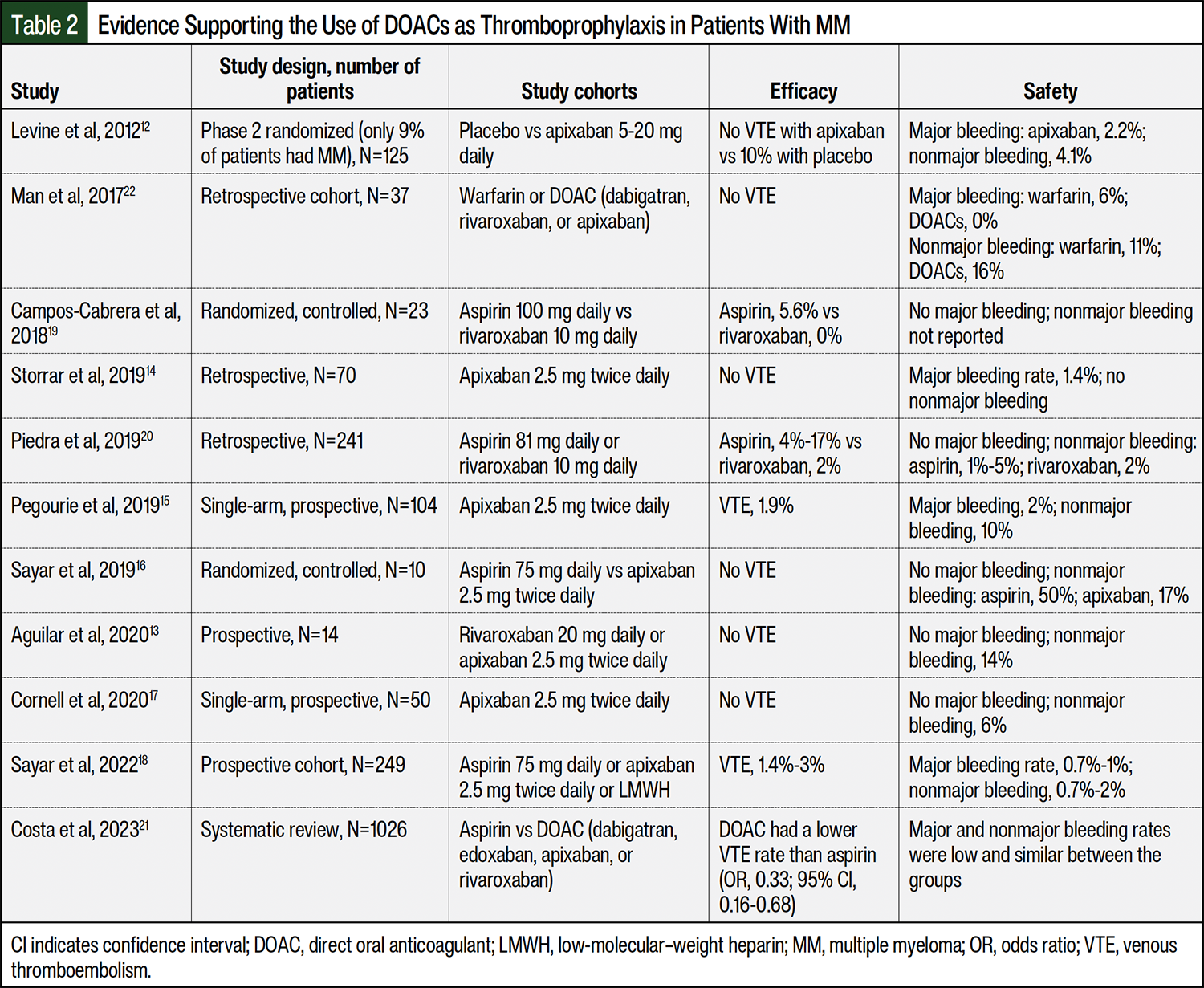

Because of the convenience of oral dosing, a lower rate of drug–drug interactions, a lack of food–drug interactions compared with warfarin, and evidence supporting the use of DOACs as thromboprophylaxis in patients with non-myeloma cancer, DOACs are an attractive option in patients with MM, despite limited data supporting their use as thromboprophylaxis in patients with MM.11 As shown in Table 2, all previous studies of DOACs in patients with MM were limited by small patient populations, retrospective study designs at a high risk for bias, and a lack of control arms.12-22 More evidence is needed to support the routine use of DOACs as thromboprophylaxis in patients with MM who have a high risk for VTE.

Our study’s objective was to investigate the safety and efficacy outcomes of DOACs as thromboprophylaxis and to characterize the incidence of thrombocytopenia and interruptions in thromboprophylaxis during induction therapy for patients newly diagnosed with MM who are receiving lenalidomide.

Methods

In this retrospective, single-center study at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, TX, we evaluated patients newly diagnosed with MM who received a lenalidomide-based induction regimen and a DOAC, either apixaban or rivaroxaban, for thromboprophylaxis. This study’s design was approved by our institutional research review board before data collection.

We identified patients via a query of the electronic medical records and analysis of the prescription fill history for patients with MM receiving a lenalidomide-based induction regimen between January 1, 2019, and June 1, 2022, who were prescribed apixaban or rivaroxaban as thromboprophylaxis. For study inclusion, patients had to be aged ≥18 years and have at least 6 months of follow-up at our center. Patients were excluded if they had an indication for anticoagulation other than primary thromboprophylaxis, documentation that DOAC therapy was not received, or if they received doses other than apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or rivaroxaban 10 mg daily.

The primary outcomes were the rates of VTE and major and minor bleeding within 6 months of starting lenalidomide-based induction therapy. VTE diagnoses were confirmed by imaging studies and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes. The secondary outcomes were the incidence of thrombocytopenia and interruptions in thromboprophylaxis within 6 months of initiating treatment with an induction regimen.

The baseline data collected from the electronic medical record at the time of the initial day of induction therapy included age, sex, race/ethnicity, weight, height, type of MM, Revised International Staging System Stage, ECOG performance status score, creatinine clearance (calculated via the Cockcroft-Gault formula), platelet count, induction treatment regimen, median dexamethasone dose, number of induction therapy cycles, receipt of an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant, IMPEDE VTE score, SAVED score, relevant comorbidities, relevant concomitant medications, and the name, dose, and duration of the DOAC prescribed.

We recorded the incidence of VTE, major and minor bleeding, thrombocytopenia, and interruptions in thromboprophylaxis via manual patient chart review. VTE events were graded in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.23 The rates of arterial thrombosis were not measured. Major bleeding was defined according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) criteria as clinically overt bleeding that is accompanied by a hemoglobin decrease by ≥2 g/dL, requiring a transfusion of ≥2 units of whole or red blood cells, occurring at a critical site, or resulting in death.24 Minor bleeding, as defined by the ISTH clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding criteria, included all events that did not meet the criteria for major bleeding but that required medical intervention, hospitalization, or the prompting of an in-person evaluation by a healthcare provider.24 Thrombocytopenia was graded according to CTCAE version 5.0,23 and the duration of interruption in thromboprophylaxis was rounded to the nearest week.

Results

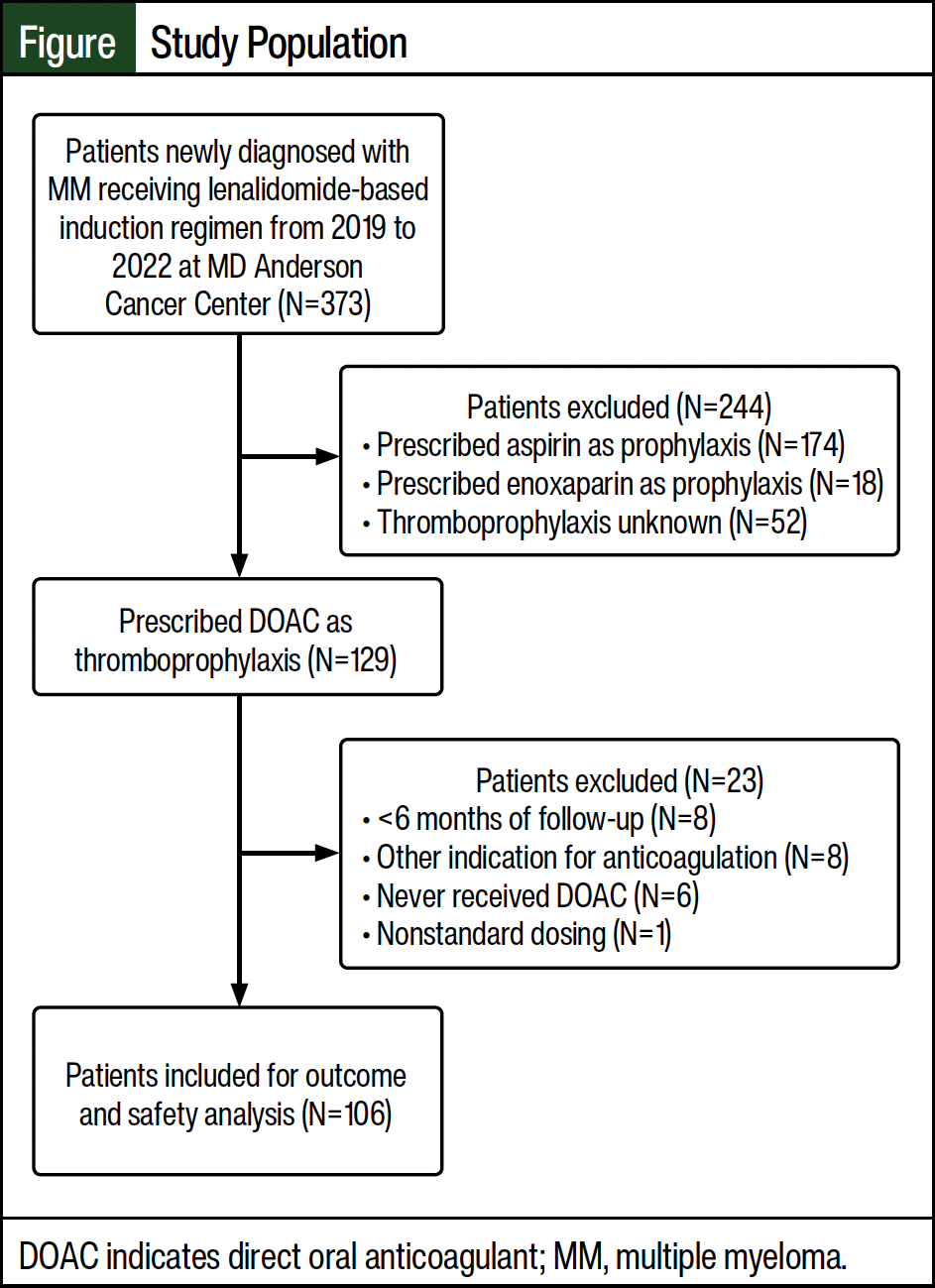

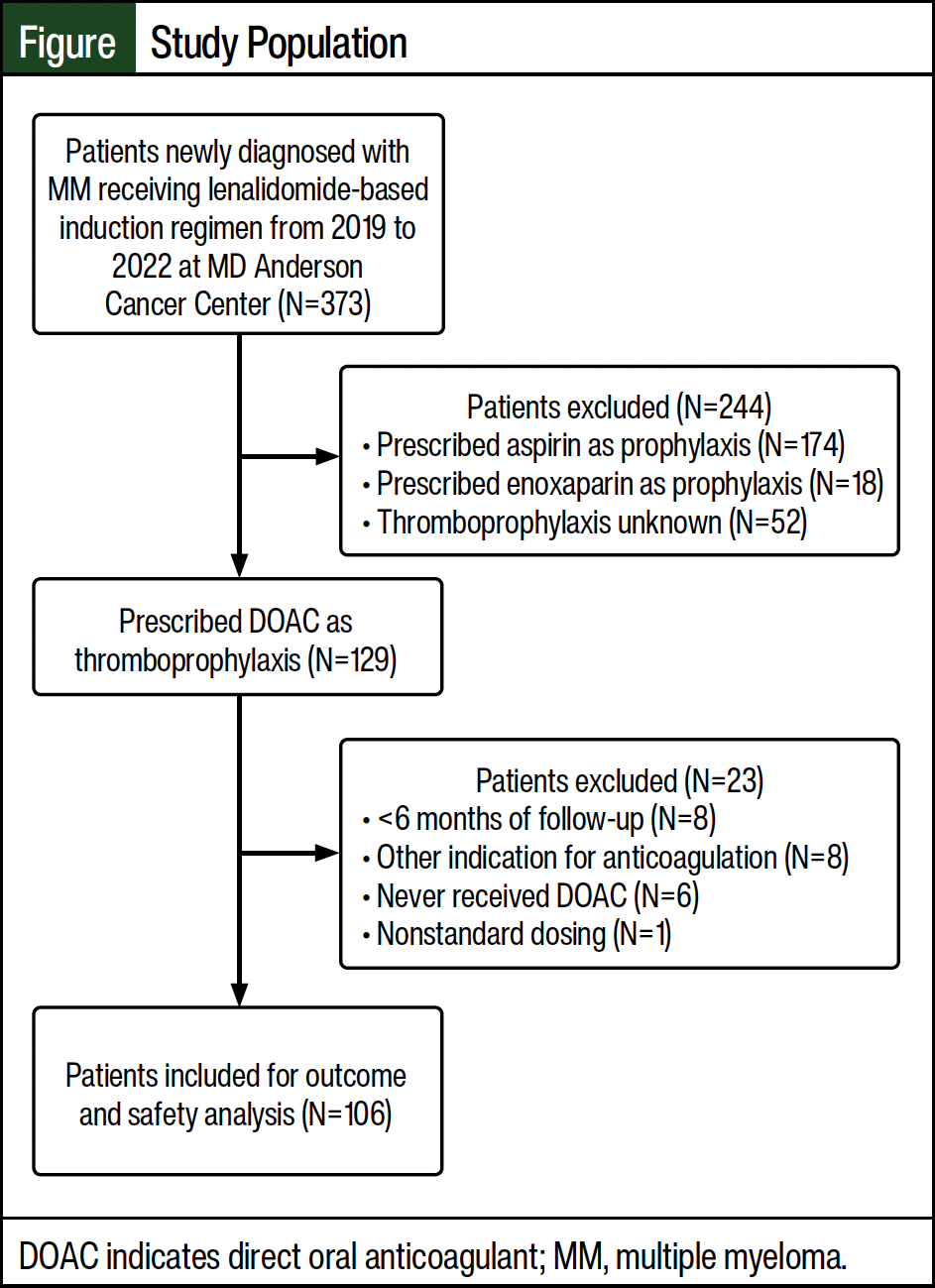

Of the initial 373 patients who were screened, 106 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in our study (Figure). Most patients who were excluded from the study received aspirin as thromboprophylaxis (N=174). Of the 106 patients evaluated for efficacy and safety outcomes, 95 patients were prescribed apixaban and 11 patients were prescribed rivaroxaban.

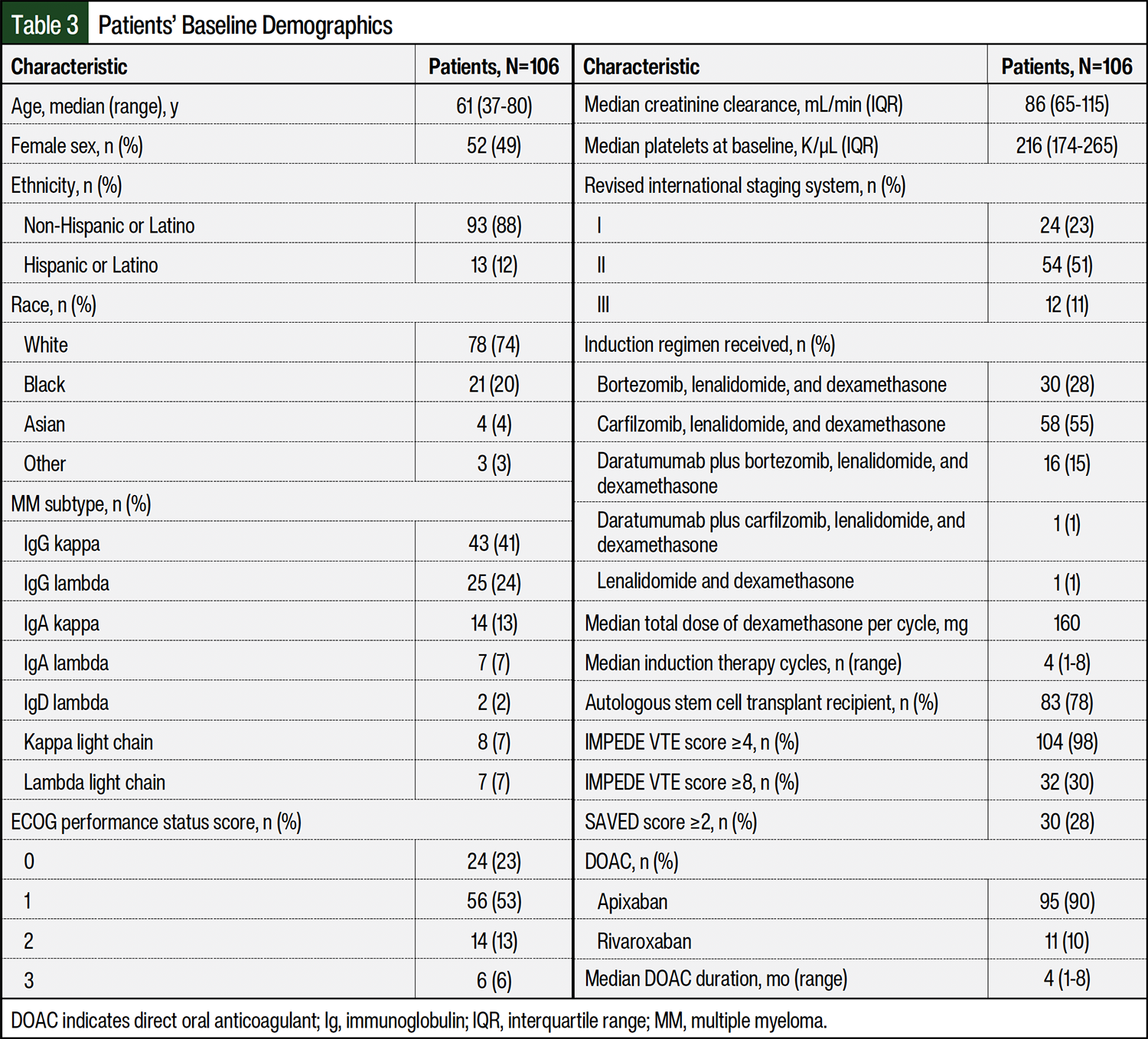

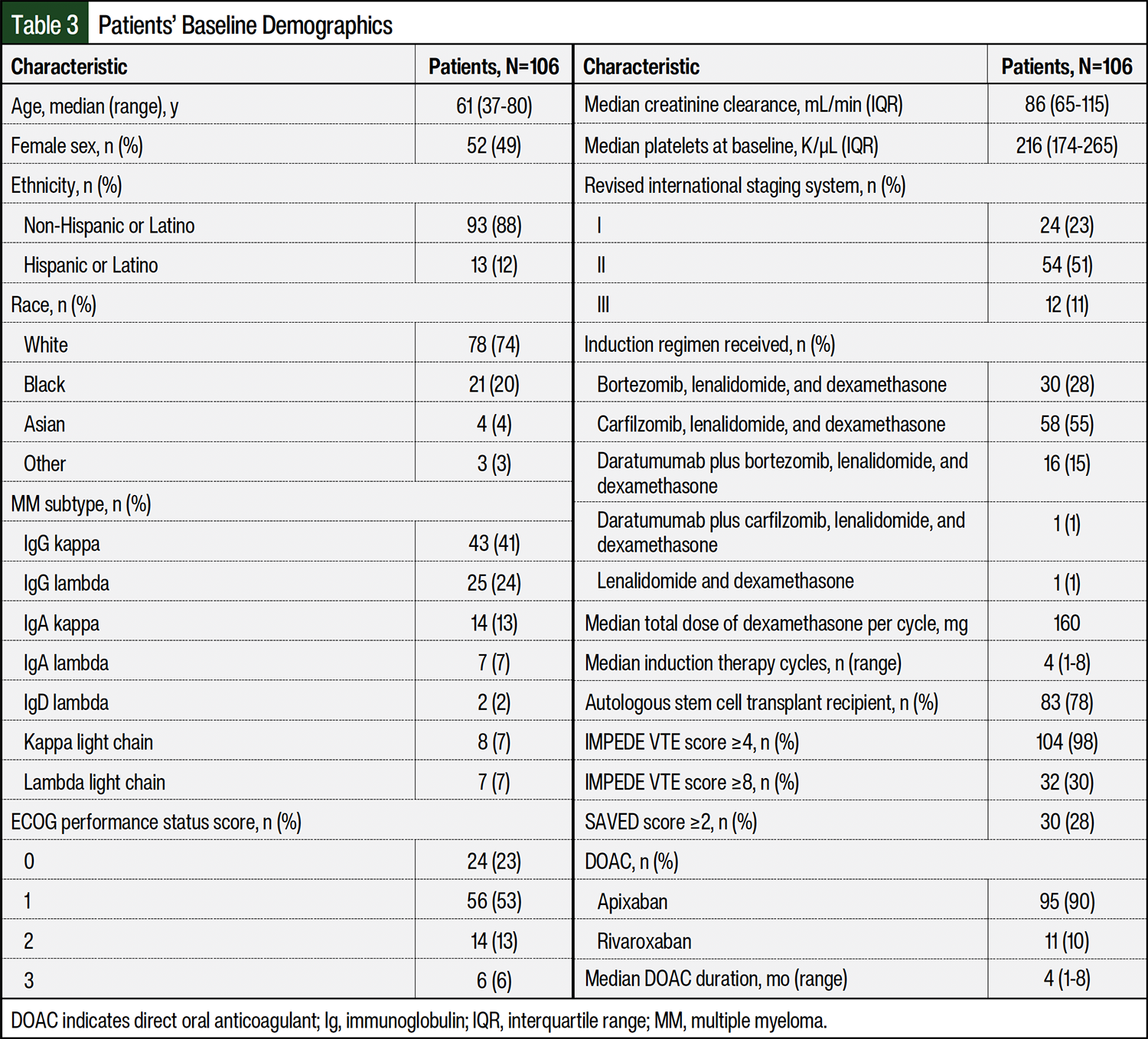

The patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 3. The most common induction regimens received were the triplet of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (55%) followed by bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (28%). The median dose of dexamethasone per cycle was considered a low dose (160 mg), the median number of lenalidomide-based induction cycles was 4, and the duration of thromboprophylaxis was 4 months. Using the IMPEDE VTE risk score threshold of ≥4, 98% of patients were classified as having at least an intermediate risk for VTE. In all, 28% and 30% of patients were classified as having a high risk for VTE based on the SAVED and IMPEDE VTE risk score thresholds of ≥2 and ≥8, respectively.

The most common (82%) VTE risk factor besides IMiD and dexamethasone use was a body mass index (BMI) of ≥25 kg/m2. Few patients at baseline received high-dose dexamethasone (13%), had surgery within the past 90 days (11%), had a pathologic fracture in the pelvis or femur (9%), had a history of VTE (8%), had used a tunneled line or central venous catheter (6%), or were aged ≥80 years (2%). None of the patients had received an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent or doxorubicin. Similarly, few patients had protective factors of Asian race (4%) or receiving prophylactic-dose aspirin (12%). None of the patients were receiving a strong inducer or inhibitor of CYP3A4 when thromboprophylaxis with a DOAC was started.

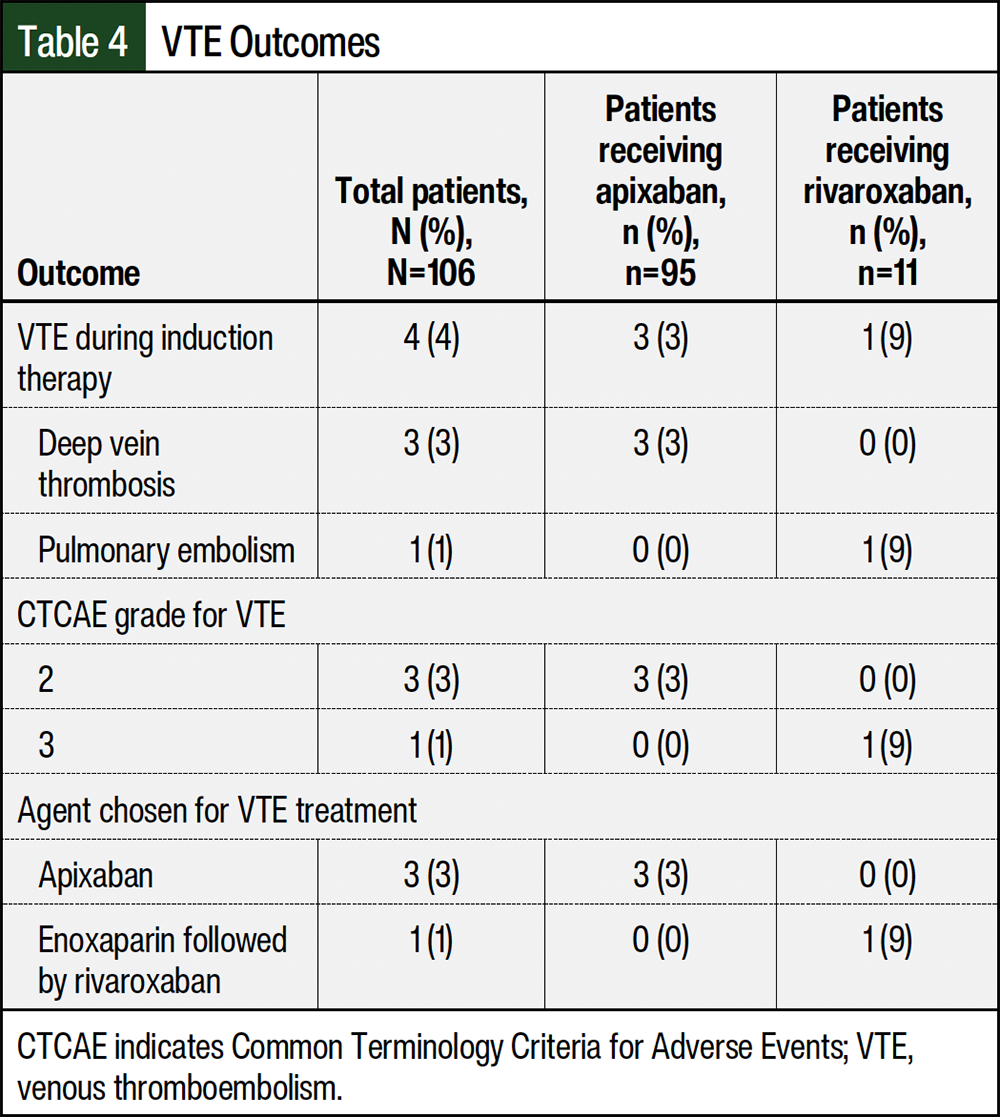

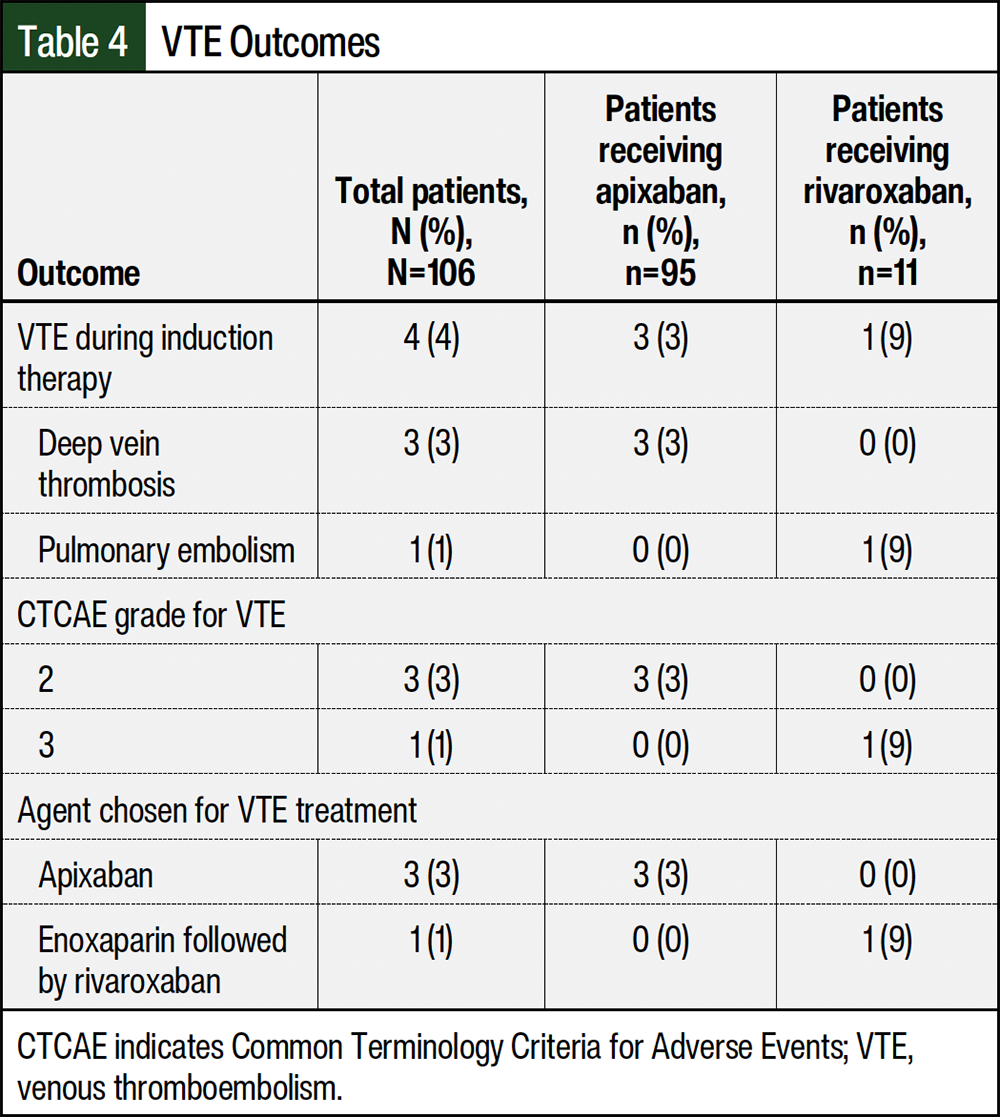

The overall incidence rate of VTE was 4% (Table 4). A total of 3 events were classified as deep vein thrombosis, whereas 1 event was a pulmonary embolism that was classified as low risk. The location of the deep vein thrombosis events included the left popliteal, portal, and internal jugular vein. None of the patients had a central line at the time of VTE diagnosis, and none of the patients were receiving a concomitant moderate or strong CYP3A4 inducer at the time of the VTE event. Surprisingly, all patients with a VTE event had an IMPEDE VTE risk score of 7, indicating moderate VTE risk, with all patients sharing the same risk factors of IMiD use (+4), receiving low-dose dexamethasone (+2), and a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2 (+1). None of the VTE events were considered life-threatening or fatal.

The agents chosen for VTE therapy were treatment-dose apixaban (N=3) and enoxaparin followed by treatment-dose rivaroxaban (N=1; Table 4). All 4 patients who had a VTE event had an IMPEDE VTE score of 7 (high risk) and a range of SAVED scores from 1 (low risk) to 3 (high risk). Two patients received induction therapy with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone, whereas the other 2 patients received bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone. The onset of VTE after starting induction therapy ranged from <1 month to 7 months (median, 3 months), and the duration of treatment ranged from 3 months to 12 months (median, 6 months).

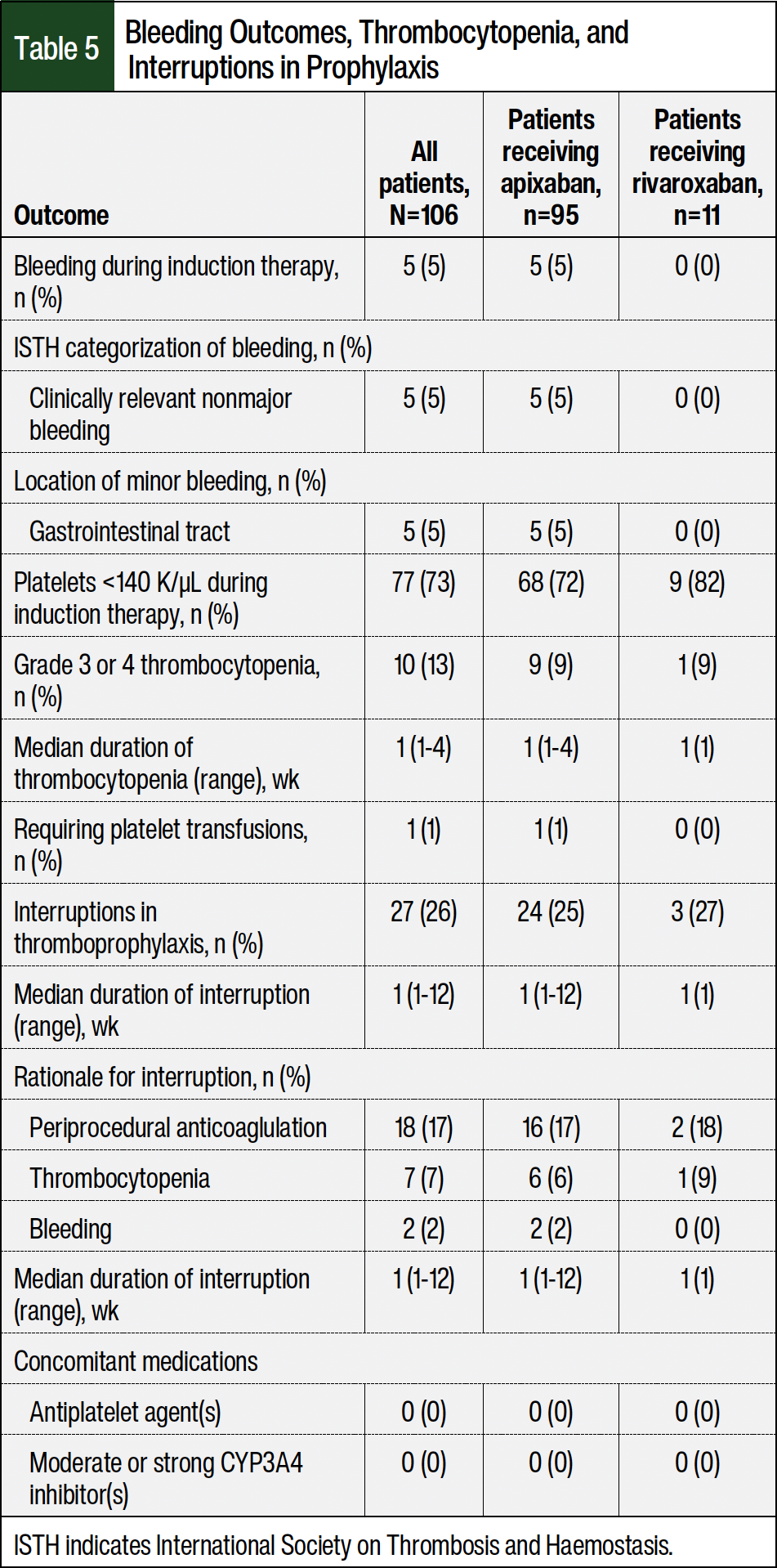

The incidence of bleeding during induction therapy was 5% (Table 5). All bleeding events were classified as clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, and there were no major bleeding events. The location of all minor bleeding events was within the gastrointestinal tract (5%). None of the patients received concomitant antiplatelets or a moderate-to-strong CYP3A4 inhibitor at the time of the bleeding; 1 patient had elevated serum creatinine. A total of 5 patients with a bleeding event had concurrent thrombocytopenia, all of which were grade 1. Similarly, 5 patients required holding thromboprophylaxis for <1 week to resolve the bleeding event, whereas 3 other patients had a bleeding event that resolved without intervention. The ages of the patients who had bleeding ranged from 48 years to 70 years. The onset of the bleeding events ranged from <1 month to 6 months from the induction therapy initiation (median, 4 months).

Discussion

The principal finding of this study was a low rate of VTE and a lack of major bleeding with DOAC thromboprophylaxis in patients newly diagnosed with MM who were receiving lenalidomide-based induction therapy. Using the IMPEDE VTE risk score, almost all patients (98%) were classified as having at least an intermediate risk for VTE and should have received a DOAC or another anticoagulant instead of aspirin based on the current NCCN guidelines. Smaller percentages of patients, 28% and 30%, were classified as having a high risk for VTE based on the SAVED and IMPEDE VTE risk scores, respectively.

The incidence of VTE in our study (4%) was close to the upper range of those in previous literature (<1%-3%).12-20,22 However, our rate of VTE is comparable with the rate of VTE in a pooled analysis of 3 clinical trials with lenalidomide-based combination regimens without thromboprophylaxis (4% vs 13%, respectively).25 One notable characteristic in patients who had VTE in our study was an elevated BMI ranging from 25 to 42 kg/m2. Data that support the use of apixaban in morbidly obese patients with a BMI of >35 to 40 kg/m2 are limited to retrospective or observational studies, with the results of 2 pharmacokinetic studies of apixaban in obese patients who weighed ≥120 kg showing a lower area under the curve than in patients who weighed 65 to 85 kg.26,27 In addition, 2 patients who had a VTE received a carfilzomib-based induction regimen.

The ENDURANCE trial that compared carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone showed a modest increase in VTE rates to 5% with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone from 2% with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone.28 Another retrospective study by Piedra and colleagues showed higher rates of VTE with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone than with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (approximately 16% vs 5%, respectively) when aspirin alone was received as thromboprophylaxis.29 One potential rationale for the higher VTE rates in our study may be the higher use of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone as induction treatment (55% vs 28%, respectively). Of the 4 VTE events, all resolved after 3 to 12 months of anticoagulation with either treatment-dose apixaban or enoxaparin followed by treatment-dose rivaroxaban.

The bleeding rate in our study (5%) was within the range of those in other studies (2%-17%).12-20,22 Furthermore, the lack of major bleeding in our study was concordant with previous studies that also showed no major bleeding events with DOACs.13,16,17,22 The low incidence of minor bleeding and the lack of major bleeding substantially add to the existing literature that demonstrates the safety of using DOACs as thromboprophylaxis in patients with MM.

One concern with providers using an anticoagulant during induction therapy is concurrent thrombocytopenia. The platelet threshold that providers within our study used to hold thromboprophylaxis was 50 K/µL (ie, CTCAE grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia). The rates of grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia within our study were low at 13% with a median duration of 1 week. Reassuringly, only 1% of patients in our study required platelet transfusions during induction therapy. Most thrombocytopenia resolved with treatment interruption and dose decreases of lenalidomide. Although 27% of patients required an interruption of thromboprophylaxis during induction therapy, only 7% of patients held their DOAC treatment for grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia and only 2% for bleeding. The most common rationale for holding thromboprophylaxis was in the periprocedural phase for elective procedures, such as kyphoplasty, a dental procedure, colonoscopy or endoscopy, or a nerve block. In addition, the median duration of holding treatment with DOACs was 1 week.

Our study is reflective of real-world practice, where providers are increasingly using DOACs as thromboprophylaxis in patients with MM because of the ease of administration and the lack of a need for laboratory monitoring.11 A strength of our study was the inclusion of only newly diagnosed patients during the initial induction treatment phase, which provided a level of standardization. Previous studies by Pegourie and colleagues and Cornell and colleagues included newly diagnosed patients, patients receiving maintenance therapy, and patients with relapsed or refractory disease, which may have confounded their results.15,17

Further studies on the ideal thromboprophylaxis agent are needed because the most recent phase 3 trials that investigated thromboprophylaxis in patients with MM who were receiving an IMiD were in 2011 and 2012.6,30 The 2011 trial by Palumbo and colleagues showed no difference in a composite event encompassing serious thromboembolic events, acute cardiovascular events, or sudden deaths between aspirin, warfarin, and enoxaparin (6%, 8%, and 5%, respectively).30 Similarly, the 2012 trial by Larocca and colleagues showed no difference in VTE rates between aspirin and enoxaparin (approximately 2% vs 1%, respectively).6 It is important to note that these trials predominantly enrolled patients with a low risk for VTE and high-risk patients were excluded. A subsequent study by Sanfilippo and colleagues in 2017 suggests that aspirin may not adequately decrease the risk for VTE in high-risk patients.31 One large systematic review and meta-analysis of patients receiving lenalidomide-based regimens with aspirin, enoxaparin, or warfarin prophylaxis showed an elevated VTE rate of 6.2%.32 Therefore, additional studies are needed to determine which patients may benefit from additional thromboprophylaxis options such as DOACs when receiving lenalidomide-based induction regimens.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its retrospective design, small sample size, lack of ability to confirm adherence, inconsistencies in the documentation of VTE and bleeding events, and patients receiving only part of their medical care at our institution. There may be confounding factors leading to a physician choosing a DOAC over aspirin for patients in our study. The small number of patients who received treatment with rivaroxaban limited our ability to compare VTE and bleeding outcomes between different types of DOACs.

In addition, our study did not evaluate whether differences in VTE and bleeding outcomes exist between patients who receive aspirin and those who receive anticoagulation prophylaxis. We also did not investigate the rates of arterial or other cardiovascular events besides VTE. Last, as a result of the retrospective nature of our study, we were unable to assess the adherence rates for patients who had VTE rates to determine whether thrombosis events were nonresponse to thromboprophylaxis or if they occurred because of nonadherence.

Conclusion

This study adds to previous research demonstrating the safety and efficacy of DOACs as thromboprophylaxis in patients with MM who are receiving lenalidomide-based induction regimens in the real-world setting. The incidence of VTE and bleeding rates in this study were low and were similar to rates in previous literature. Given the low sample size, single-center patient population, and retrospective method of data collection, the results of our study are limited in their applicability to a broader MM patient population. Additional randomized trials are needed to conclusively determine the ideal thromboprophylaxis agent and duration in patients with MM receiving induction therapy with a lenalidomide-based regimen.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Wang, Dr Luo, and Dr Primeaux have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Li W, Cornell RF, Lenihan D, et al. Cardiovascular complications of novel multiple myeloma treatments. Circulation. 2016;133:908-912.

- Blom JW, Doggen CJM, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2005;293:715-722.

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Tay J, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism in multiple myeloma patients undergoing immunomodulatory therapy with thalidomide or lenalidomide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:653-663.

- Dimopoulos MA, Leleu X, Palumbo A, et al. Expert panel consensus statement on the optimal use of pomalidomide in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2014;28:1573-1585.

- Wun T, White RH. Epidemiology of cancer-related venous thromboembolism. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2009;22:9-23.

- Larocca A, Cavallo F, Bringhen S, et al. Aspirin or enoxaparin thromboprophylaxis for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide. Blood. 2012;119:933-939.

- Palumbo A, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Prevention of thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thrombosis in myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:414-423.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): multiple myeloma. Version 2.2025. April 11, 2025. Accessed July 15, 2025. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf

- Sanfilippo KM, Luo S, Wang TF, et al. Predicting venous thromboembolism in multiple myeloma: development and validation of the IMPEDE VTE score. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:1176-1184.

- Li A, Wu Q, Luo S, et al. Derivation and validation of a risk assessment model for immunomodulatory drug-associated thrombosis among patients with multiple myeloma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:840-847.

- Swan D, Rocci A, Bradbury C, Thachil J. Venous thromboembolism in multiple myeloma – choice of prophylaxis, role of direct oral anticoagulants and special considerations. Br J Haematol. 2018;183:538-556.

- Levine MN, Gu C, Liebman HA, et al. A randomized phase II trial of apixaban for the prevention of thromboembolism in patients with metastatic cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:807-814.

- Aguilar C, Dueñas AB, Sevil F, Domínguez C. Use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as primary or secondary prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with multiple myeloma on immunomodulatory drugs. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(suppl 1):Abstract PB2098.

- Storrar NPF, Mathur A, Johnson PRE, Roddie PH. Safety and efficacy of apixaban for routine thromboprophylaxis in myeloma patients treated with thalidomide- and lenalidomide-containing regimens. Br J Haematol. 2019;185:142-144.

- Pegourie B, Karlin L, Benboubker L, et al. Apixaban for the prevention of thromboembolism in immunomodulatory-treated myeloma patients: myelaxat, a phase 2 pilot study. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:635-640.

- Sayar Z, Czuprynska J, Patel JP, et al. What are the difficulties in conducting randomised controlled trials of thromboprophylaxis in myeloma patients and how can we address these? Lessons from apixaban versus LMWH or aspirin as thromboprophylaxis in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (TiMM) feasibility clinical trial. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019;48:315-322.

- Cornell RF, Goldhaber SZ, Engelhardt BG, et al. Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism with apixaban for multiple myeloma patients receiving immunomodulatory agents. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:555-561.

- Sayar Z, Gates C, Bristogiannis S, et al. Safety and efficacy of apixaban as thromboprophylaxis in myeloma patients receiving chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study. Thromb Res. 2022;213:27-29.

- Campos-Cabrera G, Mendez-Garcia E, Campos-Cabrera S, et al. Rivaroxaban or aspirin as thromboprophylaxis in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):5068.

- Piedra KM, Hassoun H, Buie LW, et al. VTE rates and safety analysis of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients receiving carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (KRD) with or without rivaroxaban prophylaxis. Blood. 2019;134(suppl 1):1835.

- Costa TA, Felix N, Costa BA, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus aspirin for primary thromboprophylaxis in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing outpatient therapy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Br J Haematol. 2023;203:395-403.

- Man L, Morris A, Brown J, et al. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients on immunomodulatory agents. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;44:298-302.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 5.0. November 27, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2023. National Institutes of Health. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5×11.pdf

- Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692-694.

- Menon SP, Rajkumar SV, Lacy M, et al. Thromboembolic events with lenalidomide-based therapy for multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2008;112:1522-1528.

- Upreti VV, Wang J, Barrett YC, et al. Effect of extremes of body weight on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability of apixaban in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76:908-916.

- Wasan SM, Feland N, Grant R, Aston CE. Validation of apixaban anti-factor Xa assay and impact of body weight. Thromb Res. 2019;182:51-55.

- Kumar SK, Jacobus SJ, Cohen AD, et al. Carfilzomib or bortezomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma without intention for immediate autologous stem-cell transplantation (ENDURANCE): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1317-1330.

- Piedra K, Peterson T, Tan C, et al. Comparison of venous thromboembolism incidence in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients receiving bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone (RVD) or carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone (KRD) with aspirin or rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis. Br J Haematol. 2022;196:105-109.

- Palumbo A, Cavo M, Bringhen S, et al. Aspirin, warfarin, or enoxaparin thromboprophylaxis in patients with multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide: a phase III, open-label, randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:986-993.

- Sanfilippo KM, Luo S, Carson KR, Gage BF. Aspirin may be inadequate thromboprophylaxis in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;130(suppl 1):3419.

- Chakraborty R, Bin Riaz I, Malik SU, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk with contemporary lenalidomide-based regimens despite thromboprophylaxis in multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer. 2020;126:1640-1650.