Suranjana TewariAsia business correspondent, Tokyo and

Peter HoskinsBusiness reporter

Reuters

ReutersOnly four bottles of Asahi Super Dry beer are left on the shelves of Ben Thai, a cosy restaurant in the Tokyo suburb of Sengawacho.

Its owner, Sakaolath Sugizaki, expects to get a few more soon, but she says her supplier is keeping the bulk of its stock for bigger customers.

That’s because Asahi, the maker of Japan’s best-selling beer, was forced to halt production at most of its 30 factories in the country at the end of last month after being hit by a cyber-attack.

While all of its facilities in Japan – including six breweries – have now partially reopened, its computer systems are still down.

That means it has to process orders and shipments manually – using pen, paper and fax machines – resulting in much fewer shipments than before the attack.

Asahi accounts for about 40% of Japan’s beer market, so its problems are having a major impact on bars, restaurants and retailers.

The company has apologised “for any difficulties caused by the recent attack” but has not yet said when it expects its operations to be fully up and running again.

The BBC visited convenience stores and supermarkets in Tokyo and Hokkaido – where workers said they were selling their current stock and hadn’t been able to place new orders for Asahi products, which also include water and food items.

Hisako Arisawa, who runs a liquor store in Tokyo, says she is worried about her customers as she can only get a few bottles of Super Dry at a time and expects the disruption to go on for at least a month.

The problem isn’t just affecting beer, she adds, there are also shortages of Asahi’s soft drinks, such as ginger beer and soda water.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast week, some of the country’s biggest convenience store chains warned their customers to expect shortages.

FamilyMart said its Famimaru range of bottled teas, which are made by Asahi, were expected to be in short supply or out of stock.

7-Eleven halted shipments in Japan of Asahi products, while Lawsons also said it expected shortages.

Mr Nakano, who didn’t want to share his first name, works for an alcohol wholesaler.

While some shipments from Asahi have resumed, he says he is only getting about 10-20% of the normal amount.

His orders are now handwritten and taken by fax. Asahi notifies him by fax when lorries are ready to leave its factory.

Asahi also owns big brands in Europe – such as Peroni, Grolsch, and the British brewer Fuller’s – but the firm has said those operations have not been affected by the cyber-attack.

Ransomware group Qilin – which has previously hacked other major organisations – has claimed responsibility for the attack on Asahi.

It operates a platform that allows users to carry out cyber-attacks in exchange for a percentage of extortion proceeds.

Asahi has not confirmed the nature of the attack on its operations but has said data suspected to have been leaked in the hack had been found on the internet.

It is the latest in a series of cyber-attacks by other hacking groups that have hit major firms around the world, including carmaker Jaguar Land Rover and retail giant Marks and Spencer.

Travellers were delayed at a number of European airports in September after a ransomware attack disrupted check-in and boarding software.

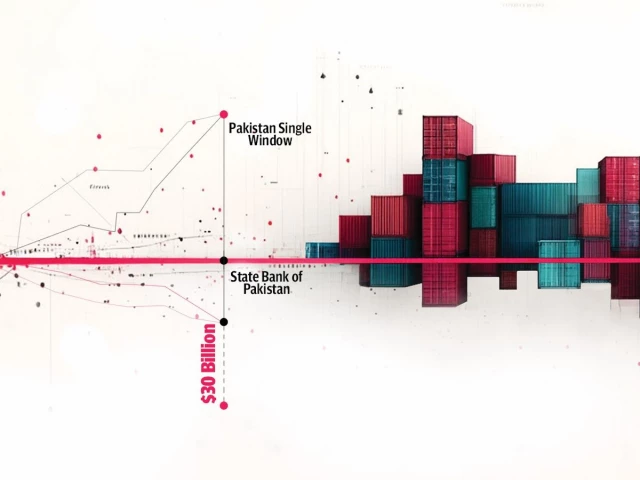

Back in Japan, a cyber-attack paralysed operations at a container terminal in the city of Nagoya for three days in 2024.

Japan Airlines was also hacked last Christmas, causing delays and cancellations to domestic flights.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesWhile Japan’s image around the world may be of a technologically advanced nation, some experts have warned it does not have enough cybersecurity professionals and has low rates of digital literacy when it comes to business software.

This issue was highlighted last year when officials finally stopped asking people to submit documents to the government using floppy disks, even though they fell out of fashion in much of the rest of the world in the 1990s.

Japan is vulnerable to cyber-attacks “given a reliance on legacy systems and a society with a high level of trust,” Cartan McLaughlin from Nihon Cyber Defence Group told the BBC.

Many organisations in the country are not prepared for attacks and are willing to pay ransoms, which makes them attractive to hackers, he added.

Speaking at a news conference this week, Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi said the Asahi cyber-attack was being investigated.

“We will continue to improve our cyber capabilities,” he added.

Earlier this year, the Japanese government passed a landmark law giving it more powers in the event of cyber-attacks.

Experts have praised the Active Cyber Defense Law (ACD), because it allows the government to share more information with companies, and also empowers the police and Japan’s Self-Defense Forces to mount their own attacks to neutralise attackers’ servers.

But that is little consolation to small businesses like Ben Thai restaurant and its customers.

Owner Sakaolath says she’s not sure what will happen the next time she puts in an order for Super Dry, and nor do many others across Japan.

Additional reporting by Chie Kobayashi in Tokyo