- Campbell leads West Indies fightback against Kuldeep-inspired India France 24

- Ind WI 2nd Test – Kuldeep Yadav’s endless bag of tricks ESPNcricinfo

- Spinners keep India in command Cricket Pakistan

- Rampaging Kuldeep reduces West Indies to 217-8

Blog

-

Campbell leads West Indies fightback against Kuldeep-inspired India – France 24

-

Pakistani, Afghan forces exchange deadly border fire: What’s next? | Explainer News

Pakistani and Afghan forces have exchanged deadly fire at multiple locations along their border, and the two sides claim to have captured and destroyed border posts in one of the worst border clashes in recent years.

The Taliban administration’s…

Continue Reading

-

Microsoft Word Has Started Automatically Saving Your Docs to the Cloud

Everybody has been there. You’re banging out the perfect Word doc, and the power cuts out before you can hit save. Last week’s Microsoft Word update makes that worry a thing of the past, as long as you have internet while you’re…

Continue Reading

-

Buffalo Bills at Atlanta Falcons Game Predictions

What we’re hearing on the Bills: Buffalo’s offense has an extra day to prepare after the team’s first loss, which was also the first time it failed to score 30 points this season. One objective is reducing the turnovers (three vs. New…

Continue Reading

-

Sparkle introduces the C741-6U-Dual 16P server that combines 32 Intel GPUs and PCIe 5.0 connectivity

- Sparkle’s dense PCIe 5.0 design offers lower-cost entry into AI and data research

- Up to 32 Intel GPUs deliver 768GB VRAM for scalable AI computing

- 10,800W redundant power system and advanced cooling enable continuous heavy workloads

Taiwanese…

Continue Reading

-

Men’s Golf Hosts the 41st Annual Georgetown Intercollegiate

WASHINGTON – The Georgetown University men’s golf team is set to host the 41st Annual Georgetown Intercollegiate…

Continue Reading

-

How FanDuel and DraftKings Have Helped Fuel Gambling Addiction

F

or Andrew Douglas, bottom was seven cops banging on the door of his apartment. He’d sharpened the knife “good,” filled the bathtub with water, and downed a vial of Coumadin to bleed out faster. Had his dad not sensed something and dialed 911, Andrew, a star baseball player turned gambling addict in college, would have quietly checked out at age 33, leaving his twin infant sons, his guilt-crippled parents, and many thousands of dollars in gambling debts behind.For Jonah, bottom wasn’t failing out of college and mulling suicide. Nor was it the month in a Florida rehab, where, for some fool reason, they let him have his cellphone and he bet money he’d stolen from family on four-legged parlay bets. (More on parlays later.) No, for Jonah, a lacrosse player at a powerhouse program, bottom was crossing the last bridge of honor: trading inside info with players at other schools to cover the over/under on games they bet.

For the seven mostly young men sitting around this table, bottom was a grave of their own digging — a hole so deep that their cries for help went unheard. “My thoughts were too crazy, I thought that no one would get them,” says Marcus, a mid-twentysomething dressed like a gamer: black glasses, high-top Chucks, and a Playskool-colored sweatshirt. At his bottom, he was staring out the window of his apartment, weighing whether a fall from five flights up would kill or merely maim him. “I got to where suicide sounded sane.” (Excepting Andrew, above, the gamblers in this story spoke in exchange for anonymity.)

We’re lunching at a sports bar in a Philadelphia suburb, picking at taste-free wings and waffle fries. It’s a curious place to bring a group of recovering gamblers, but the man at the head of the table has his reasons. Harry Levant has always been a rower against the river: a former criminal-defense attorney who lost his license, and nearly lost his life, to his own gambling jones a decade back; a second-chance crusader and addictions counselor who mainly treats folks gutted by gambling disorders; and a peripatetic opponent of the online gambling behemoths DraftKings and FanDuel, and the other sports-betting operators (hereafter, SBOs). Forty weeks a year, Levant’s somewhere in the air, lecturing state legislators and groups of physicians about the betting apps’ ploys and snares, as well as the harms he says they’ve levied on Gen Z males. That grail of Levant’s reads lonely and self-devouring: the mania of the gambler repurposed for public service. “Every addictive product has regulations,” says Levant. “Why is this the only one without them?”

As his clients tell their stories, a loose narrative hangs together. With an exception here and there, most of these guys started gambling as teens, playing lunchroom hold-em and NFL parlays for a buck or two a throw. Then they got to college, rooming and running with older kids. Here, suddenly, everyone seemed to be in action, be it betting stupid sums on esports soccer or throwing 15 bucks at a five-legged parlay that paid out 20 to one but rarely cashed. (A parlay is a combo bet on two or more outcomes; to collect, you must win each outcome, or “leg.” Should you hit on four legs but miss the fifth, you lose whatever money you put down. Oh, and the odds of winning that five-legged parlay? Less than five percent.)

Hospitalized after a suicide attempt due to gambling debts, Andrew Douglas says nurses turned on the NBA Finals and handed him his phone: “I gambled away my last $100.”

The portals and drivers for much of this action were the giant sports-bet apps. On the party-colored killing floor of online gambling, FanDuel and DraftKings own most of the take, cornering 80 percent of the mobile bet market in this country. Eight years ago, Americans placed around $5 billion in sports bets. Last year, that number zoomed to nearly $150 billion; by 2028, we’ll have bet — and lost — a trillion dollars since 2018. That was the year the Supreme Court reversed a federal ban on legalized gambling, freeing each state to partner with Big Sports Bet and feed their residents, especially the young ones, to the wolves.

FanDuel and DraftKings wasted no time. They’d spent hundreds of millions of dollars, and the better part of a decade, carpet-bombing the airwaves with ads. Now, they paid kings’ ransoms to each of the major sports leagues in exchange for their data and branding, and partnered with, or bought up, AI firms to help target their users’ browsing habits, favorite teams, and sports. “DraftKings, for one, bought SimpleBet, the biggest AI firm in this space, to turn data into in-game microbets,” says Levant. “Then they tracked and used their customers’ data to determine which of them preferred making constant, nonstop bets — and pushed those bets their way.”

Bombarded by promos for FanDuel and DraftKings — “Get a $1,000 deposit bonus!” reads one DraftKings blast — underage boys pressed their parents to open accounts, often linked to dad’s ID and banking info, critics claim. Or they surreptitiously opened accounts without their parents’ knowledge, as teens have done with verboten vices since the dawn of time. “Young guys have always bonded around sports; it’s wired into their pack behavior,” says Levant. “What the apps do is monetize that pack behavior: Guys bond over sports bets, not sports, now.”

Reached for comment on the matter, DraftKings and FanDuel pushed back on the contention that underage gambling is rampant on their apps, pointing to the safeguards they have in place. “DraftKings is committed to providing a legal, regulated, and responsible gaming environment for adults,” wrote a spokesperson for the company. “We employ advanced Know Your Customer (KYC) technology, relied on by the financial industry and law enforcement, to verify the age of our customers. Any use of our platform by minors violates both our Terms of Use and the law, and we actively monitor to detect and report this prohibited activity.”

It bears noting that neither SBO agreed to on-the-record interviews for this piece. Instead, they responded with written statements, like the one from FanDuel, as follows:

“As a legal, licensed and regulated operator, we have focused on the importance of educating college students on the risks associated with gambling. Notably, recovered problem gambler and national TV host Craig Carton brings lived experience and well-documented struggles with gambling to campuses through the FanDuel Responsible Gaming College Tour. Additionally, we have extended our education efforts to reach families by creating the Trusted Voices parent portal which provides tools and resources to talk to young people about gambling, associated risks, how to recognize warning signs and where to go for support.”

To be clear, most adults who gamble on sports do so as a harmless time suck, a way to zest their weekend football viewing. And countless teens put 10 spots on ballgames without getting dragged into addiction. “There are kids with a healthy relationship to money who can gamble casually on sports,” says Jody Bechtold, the CEO and founder of the Better Institute in Pittsburgh and a distinguished lecturer on gambling addiction. “But there are lots of other kids wired differently these days — high anxiety, ADHD, over-immersion in video games — who’re at much higher risk of addiction.” That’s especially so for kids “from affluent families who never learned the value of a dollar. Money’s supposed to hurt when you lose it,” but they were raised on “all things cashless: Venmo, PayPal, you name it.”

Two years ago, the NCAA published a study on the steep surge of gambling on college campuses. It found that 67 percent of students living on campus were betting on sports — though simple math tells us that the large majority of those bettors likely wouldn’t have been of legal age to do so. Worse, many engaged in a particularly rash form of gaming, making high-speed wagers on in-game action — a pernicious new product called microbetting. Last year, a study by the National Council on Problem Gambling found that betting on campus had surged to 75 percent — and that six percent of students were addicted to gambling, or nearly double the national average.

And who on campus is qualified to treat this gusher of gambling addictions? Essentially no one, per the experts I talked to. “Colleges aren’t set up to treat [six percent] of their students,” says Jim Lange, the executive director of the Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Drug Misuse Prevention and Recovery at Ohio State University. “That isn’t our business model, and never will be.” He added that most schools don’t even know they have a problem: Gambling is scarcely mentioned in the National Collegiate Health Assessment, the standard tool used by schools to track drug and alcohol misuse by students.

None of those stats is news to the young men sitting at this table. “When I owed money to every kid I knew and was betting on Chinese ping-pong at 4 a.m., I tried going for counseling on campus,” says Marcus, the gamer kid. “As I’m talking to the counselor, she’s pulling a manual off the shelf, looking up [the definition of] ‘problem gambling.’”

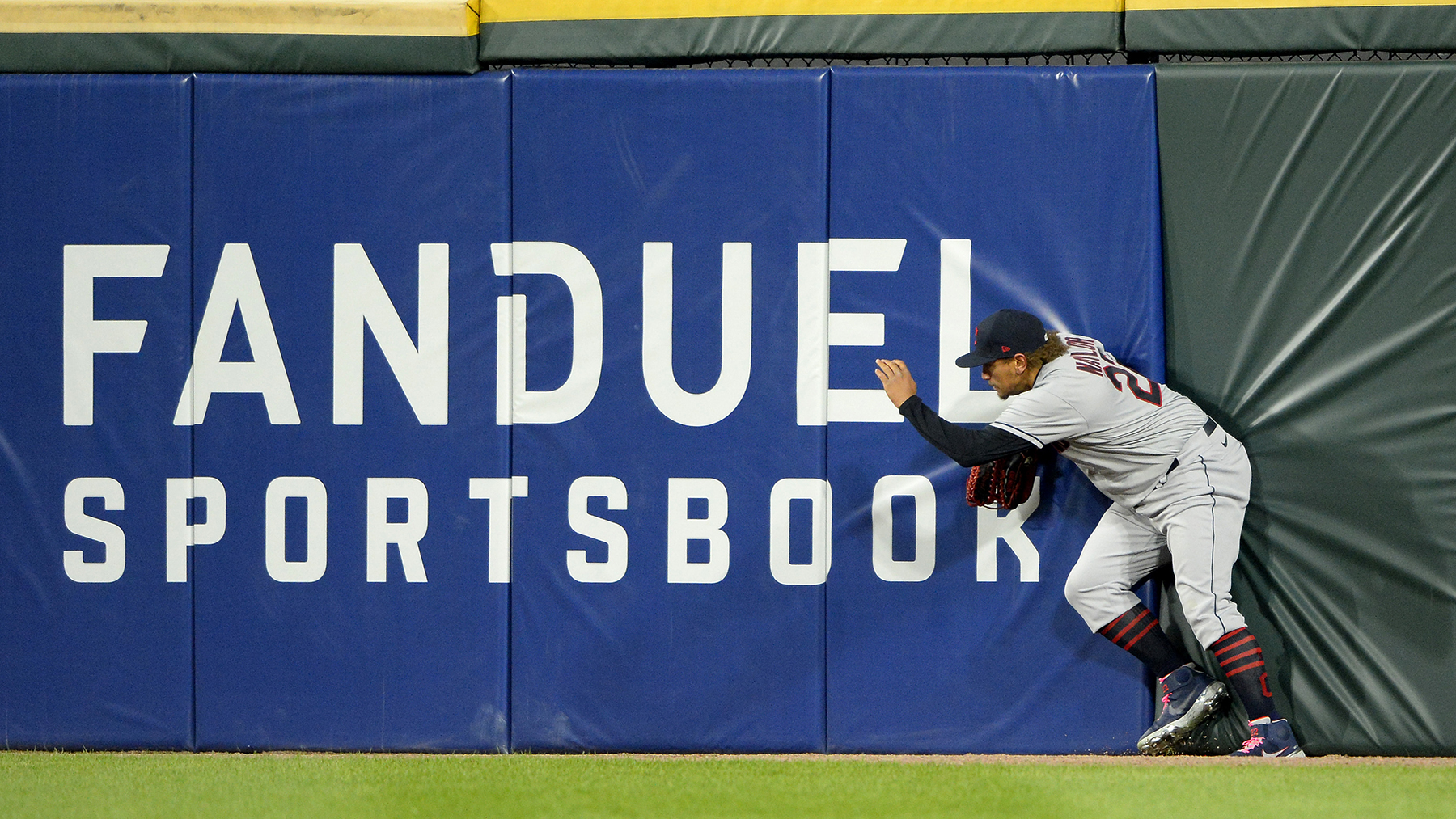

FanDuel and DraftKings have paid king’s ransoms to each of the major sports leagues in exchange for their data and partnered with AI firms to help target users’ habits.

Ron Vesely/Getty Images

“In the hospital, where I was hooked up to a bunch of IVs [after his failed suicide bid], they turned the NBA Finals on and gave me my phone; I gambled away my last $100,” says Andrew, the ex-baseball player. Things were no better during his 30-day stay at an addiction clinic in Florida. “They didn’t touch on gambling at all.” So, too, for Jonah, the former lacrosse player, sent to an out-of-state facility at 21. “This place knew nothing about gambling addiction. They gave us two hours of phone time a day, and I set up a VPN to bet in Philly.”

I hear a collective intake of breath as Jonah wraps his story. For all the suffering at this table, there’s a redemptive kinship as well, and a recognition that feels like rescue. The six percent of college kids who lose $500 or more in a day? “We used to be those kids,” says Marcus, to grunts and knowing head nods. “This is what it looks like, five years later.” Thousands of dollars stolen from a doting grandma. A bride empaupered months after her wedding. Betrayals so base they can’t be spoken to other people — but with this group, there are no secrets or judgments; only gratitude for the chance to come clean.

Eight years ago, Americans placed around $5 billion in sports bets. Last year, that number zoomed to nearly $150 billion

“After all those months and years in the cold, here you’re among friends who know exactly what you’ve gone through,” says Levant. “And all I ask in return from these guys: Don’t make a bet today.”

Andrew cuts in here to show me his phone. “Look at that top email, from Caesars,” he says. It reads, Your mystery bonus is here. “Four years since I shut down that app, they’re still tryna get their hooks in me.”

“And that,” says Levant, “is why I chose this place.” He points to the flat-panels mounted above the tables, 50 or 60 sets tuned to Fox Sports 1 or the umpteenth rerun of “First Take.” Every last one of them posts a ticker at the bottom: Odds brought to you by either FanDuel or DraftKings. “This is what these guys have to live with,” says Levant. “They can’t run from sports or those fucking apps. All they can do is change their response.”

A Caesars Sportsbook logo looms large over the scoreboard at Rate Field in Chicago.

Patrick Gorski/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

MALIK BEASLEY, A SIZZLING SCORER and prime free agent, may never see the floor in another game. After nearly $60 million made in the NBA, he’s awash in debt and unwanted by teams after a federal DA poked through his gambling tabs. (Recently cleared in that probe, he remains unsigned as basketball season approaches.) Emmanuel Clase is one of the best closers in baseball, but he won’t get to throw another pitch until the sport gets done scouring his prop-bet plays. Clase faces a lifetime ban if MLB can prove he engaged in spot-fixing, the practice of shading his own stat lines by intentionally sailing a slider over his catcher’s head. Jontay Porter could be headed to prison shortly: The NBA center copped to conspiracy to commit wire fraud recently for his part in a prop-bet ring. And Ippei Mizuhara is doing fed time already for stealing millions from his famous boss, Shohei Ohtani, to pay off gambling debts. If men who have everything can’t stop betting long enough to save their prized careers, how will we keep a generation of teens from taking a match to their futures?

We find ourselves on the cusp of this disaster thanks in part to a petition brought in 2018 by Gov. Phil Murphy of New Jersey. Murphy and his predecessor, Gov. Chris Christie, filed a brief with the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking to decriminalize wagers on sports in their state. They were suing to unleash a product so destructive that in 2013 the doctors and clinicians of the American Psychiatric Association added “gambling disorder” to the list of substance disorders in their revised standard text, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Volume 5.

It was an extraordinary upgrade, says Levant, the first of its kind: warning readers of a “substance” they couldn’t smoke, shoot, or snort, but which was nonetheless “highly addictive” and “similar in nature to heroin, opioids, tobacco, alcohol, and cocaine.” “We reclassified gambling because it shared the symptomology of classic narcotic addiction, “ says Dr. Petros Levounis, past president of the APA. “We’re greatly concerned now because of the rise in sports betting. There’s a striking likeness to the tobacco and opioid industries — and there’s consensus among us that those industries committed crimes that resulted in suffering and death.”

(Approached for comment, Murphy sent this boilerplate: “The Murphy Administration is concerned by the growing national epidemic of online sports-betting addiction, particularly among young men. What begins as occasional recreational betting too often spirals into financial instability, anxiety and depression, and high-risk habits. Our Administration is committed to mitigating the risks associated with problem gambling, including expanding treatment options and holding bad operators accountable.”)

FanDuel and DraftKings have cornered 80 percent of the mobile sports-bet market in America.

Rob Carr/Getty Images

Harmful substances, such as alcohol and narcotics, are typically regulated and controlled. But when presented with what some experts call “the biggest public health threat since Big Tobacco,” SCOTUS killed the only law shielding Americans from the corporate bet sharks. That law, called PASPA (Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act), did precisely what its title proposed. It protected pro and college sports leagues from point-shave rings; kept the Mob (and enraged bettors) off the backs of the players; and put so much physical distance between gamblers and casinos that they couldn’t lose their shirts on a passing hunch. To be sure, problem gamblers found their way around it, opening accounts with offshore sportsbooks or a local guy-who-knew-a-guy. But the damage was contained to the vulnerable few, which is about the best you can hope for from a law.

What followed, post-PASPA, was so predictable, you couldn’t have gotten odds for it at Vegas. A sanctimonious foe of sportsbooks for decades, the NFL immediately entered talks with FanDuel and DraftKings. For billions in betting revenue, the league leased those firms the rights to its stat packs, metrics, and branding. That proprietary data enabled the apps to launch a brand-new product: live, in-game wagers on practically anything that happened on field.

No longer were kids forced to wait hours on an outcome; now, they could bet on every play and every player through AI-brokered props in real time. That phenomenon, called microbetting, forever changed gambling by turbo-boosting the speed of betting behaviors. The effect of microbetting, if not its intent, is to induce a fugue state that keeps users in action. “You lose track of time and space, and next thing you know, you’re betting Indian cricket at 4 a.m.,” says Marcus. “I don’t even know the rules of cricket. Those fuckin’ matches go on for three days!”

Every major pro sports league followed football’s lead, selling their data for a slice of the sports-bet pie. The effect on problem gamblers was catastrophic. “I went from betting money lines on baseball games to betting the number of runs scored in every inning,” says Frankie, a client of Levant’s in his late twenties with a South Philly brogue and a shiny widow’s peak. “Any money left at the end of the night, I’m flipping to FanDuel’s casino. Then it’s slots and blackjack till I bust, and now I’m betting Chinese ping-pong at 3 a.m.” A year ago May, Frankie married his sweetheart in a grand Italian wedding. The guests sent them off with a pillowcase full of cash. Behind his wife’s back, Frankie lost all the cash, then defaulted on the mortgage for their house. “I didn’t know where to turn,” he says. “Suicide was my only option till I found Harry.”

Two years ago, the NCAA published a study on the steep surge of gambling on college campuses. It found that 67 percent of students living on campus were betting on sports

Those microbets and parlay packs that hooked Levant’s clients are the SBOs’ profit centers. How do we know this? Because the apps themselves say so: They’re the bets featured in their ads. Kevin Hart, Rob Gronkowski, Tom Brady, LeBron James: You can’t shut them up and make them go away when they’re touting props and parlays in every promo. Nor can you squelch their motormouthed peers on the pods and sports-bet shows: the Bill Simmonses and Charles Barkleys and Scott Van Pelts, who’ve merrily boarded the gravy train as “ambassadors” for the SBOs. (Approached for comment, Simmons, Barkley and Van Pelt declined to speak.) “Among the dangers of celebrity endorsements is the normalization of an addictive product,” says Levant. “They’re accepting enormous sums to push [that] addictive product on an increasingly younger audience.”

AFTER THE FALL OF PASPA, states raced one another to the betting window, smelling 10-figure windfalls in new taxes. Thirty-nine states plus D.C. and Puerto Rico passed bills that legalized the sports-bet racket. The ensuing carnage was swift and savage. New callers flooded the toll-free hotlines at 1-800-GAMBLER, and frantically searched the web for help, googling “gambling addiction” online. The state of New Jersey saw a nearly 300 percent spike in hotline calls in the first five years of legal betting. (Around six percent of its residents now suffer from gambling disorders — or three times the national average, per a Rutgers survey.) In Connecticut, the number of hotline calls increased 200 percent in the first two years — and the crisis was most acute among young men.

“Forty percent of those calls are coming from twentysomething males,” says Diana Goode, the executive director of the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, who likens the legalization of gambling to the opioid crisis. “It’s literally the same thing they did with pain pills. These companies hand out free samples [i.e., welcome bonuses] to get [young men] addicted to betting.”

Gambling-addiction expert Jody Bechtold says young men are especially susceptible to the dangers of this culture because they’ve grown up immersed “in a stew of ads” from the Big Two betting apps.

Brett Carlsen/Getty Images

I put the obvious question to clinician after clinician: Why are young people, males in particular, so susceptible to sports-bet apps? Bechtold, the founder and director of the Better Institute in Pittsburgh, began with the mile-high view. “This generation was basically bred for addiction, [having been] raised on cellphones inches from their faces.” The feeds on those devices “disrupted their neural wiring,” leaving them anxious, impulsive, and susceptible to “stims that are quick and constant onscreen.” Their online childhoods also robbed them of life skills best learned by leaving the house. Fiscal savvy gained by working part-time jobs. Risk awareness from running the streets, and an acquired sense of consequences from actions. “When these kids go bust, time after time it’s the parents who bail them out,” says Bechtold. “Every family I deal with, I say, ‘Quit giving the kid money!’ And Mom says, ‘Oh, I’m not ready to do that yet.’”

Bechtold says these things not to shame her clients, but to name the preconditions that make them targets. They’ve grown up immersed “in a stew of ads” from the Big Two betting apps; been chased across the web by their pings and promotions; and been told by the celebrities they trust most to think that betting’s how winners have fun. It normalizes gambling as “something cool to do with your friends,” she says. Now layer on the male-skewing lubricant of sports, and you’ve built “a mass addiction machine,” says Matt Gaskell, the clinical lead for the NHS Northern Gambling Service in England. “These companies engineered a product that exploits the reward pathways” of young brains. “The constant crackle of dopamine keeps them playing” — and then a big bump, equivalent to a “spike of heroin,” is triggered by “a win on their team.” Eventually, though, the wins and losses cease to matter. What keeps these kids in action is “that neurochemical feed that fires the desire centers in the brain.”

Gaskell’s had a decade-plus jump on his peers: Britain legalized mobile sports bets in 2005. The fallout has been tragic. “We have an estimated one to two suicides a day in England, and many of the ones I know of are of young men from middle-class families with university training” he says. Rather than confront the SBOs by slapping limits on their ads and promos — “our kids see 1,600 gambling logos in a 90-minute [soccer] match onscreen,” says Gaskell — the British government lamely lists “gambling disorder” as an official cause of death. “This industry has captured our policymakers with its billions, as I expect it’s done with yours. So the warning from over here is, expect disaster.”

EVER WONDER WHAT LIFE’S LIKE with a serpent on your shoulder, whispering in your ear to bet the Braves? For Andrew, the ex-third baseman in college, that forked-tongue enticer gave him no quarter, hissing Check the bonus! at 6 a.m. “Between the voice in my head and the texts from the sportsbooks, I wasn’t really sleeping a whole lot,” he says in his honey-maple drawl from the Carolinas. “Every night, I’d tell myself, ‘That’s your last bet.’ Then every morning, I’d get up, see the bonus on my phone, and bet double what I did the day before.”

He’s calling from his flat in eastern Pennsylvania, a bachelor pad he’s put through the wringer. There are gashes in the walls he’s just getting around to fixing: holes he made throwing weights and plates after losing thousands of dollars in three hours. “I’ve never hit anyone in my life,” he says. “But I’ve got a hell of an arm.” Between September of 2020, when he moved up from Atlanta to join the mother of his unborn twins in Pennsylvania, and May of 2024, when he placed his last wager, he bet more than a million dollars, he says, on live, long-shot parlays and props. He’s not sure how much of that was lost on the apps, but concedes it was “a lot.”

A study by the National Council on Problem Gambling found that betting on campus had surged to 75 percent — and that six percent of students were addicted to gambling, or nearly double the national average

He says he stole cash from his parents on visits home to Greenville, and guilted them into stopgap loans he knew he’d never repay. On blue-sky weeks when he won more than he lost, he’d go out and buy himself something he cherished — a new titanium driver; a pricey pair of Jordans — then sell them on for half when he went bust. “I’d walk around my place whenever I hit zero, seeing everything I owned as dollar signs.” His beloved baseball glove; the cashmere quarter-zips his grandma bought him for Christmas — anything to raise a hundred bucks and feed the addiction.

Andrew got addicted to betting in college, playing — and hitting — his first-ever backdoor cover. “I had Duke in March Madness, and was just about to lose,” he recalls. But then a ref blew the whistle as the buzzer sounded, giving Duke two meaningless free throws while up by four. With a make on the second, Duke won by five, miraculously beating the spread of 4 1/2, per Andrew’s telling. His brain went kablooey on dopamine. “I can’t even describe it — it was the best feeling ever. I thought it was gonna work like that all the time.”

Gambling experts talk about the “first-win trap” — a neurochemical surge that swamps the pleasure center, sparking delirium only matched by high-test heroin. “The reward’s beyond anything in our day-to-day lives,” says Gaskell. “It’s literally off the scale we see in” brain scans. “There’s a reason we call gambling a substance disorder,” says Levant. “But the substance isn’t the dough — it’s the dopa.”

Andrew gave up baseball, got a degree in health fitness, and earned a good living as a trainer in Atlanta. He was constantly in the hole, though, laying a dozen bets a day with the bookies or the offshore apps. Then he met a girl and moved her into his place. Months later, she was pregnant with their twins. “She’d no idea I gambled; no one did, till finally my parents caught on.” That’s the core difference between gamblers and other addicts. There’s nothing physical that gives them away: no unexplained weight loss; no cocktail-hour slurring. That secrecy, born of shame, can destroy a spouse and family. They don’t find out that their loved one’s stolen from them till the marshals are at the door with eviction papers.

In 2023, the Public Health Advocacy Institute filed a class-action consumer-fraud lawsuit against DraftKings. A judge rejected the company’s motion to dismiss.

Mark Cunningham/MLB Photos/Getty Images

For every person hiding a gambling disorder, six people in their orbit are impacted financially, according to the World Health Organization. The collateral impacts of new gambling addictions are just now being charted by clinicians. Among states that have legalized sports-bet apps, bankruptcies are up by 30,000 a year, per a USC-UCLA study still in progress. A second study, from Northwestern, found that eight percent of the households in legal-gambling states were wagering on SBOs — and that every dollar spent on those apps cost households double in net-worth losses.

And so states that took the bait of new-tax windfalls find themselves in a hole. Who’s going to cover the living expenses of families ruined by problem bettors? And who’s going to pay for those bettors’ treatment when, or if, they seek help? (Less than 10 percent of gambling addicts ever come in for counseling, per the National Council on Problem Gambling.) Of all the grim ephemera linked to legal gambling, this fact might be the starkest: For every dollar paid in taxes by SBOs, the states spend, on average, .0009 cents providing therapy for the addicts they’ve helped create, according to theNCPG.

WHAT’S A YOUNG MAN TO DO when all the outlets he watches — ESPN, Paramount+, Peacock, Fox Sports — either own or have partnered with a sportsbook? When FanDuel and DraftKings push him their bet boosts while he’s scrolling reels? When SportsCenter plates him up a side of “Bad Beats” to pair with its “Top Ten Plays”?

The effect of all that noise is to sell a tautology: that gambling is harmless fun when done in measure. It’s both the message and the method of the SBOs, who affix their buzzwords — “responsible gaming,” or RG — to the toe plate in all their ads. I called their collective trade rep, the American Gaming Association, to get a sense of RG in practice. Joe Maloney, a senior vice president, explained it to me — after expressing shock that kids use the apps. “The prevailing legal age for wagering is 21,” he told me. “We verify identities, we verify ages — and if a parent is opening [an account] for the use of a minor, that’s a violation of our terms of service. And if it’s found to have been done, then those individuals are banned from having accounts at these sites.”

“If there’s college kids jumping out of windows now, we need to see those accounts to figure out why. We have a moral obligation to those kids and their families. Otherwise, we’ll lose a generation.”

I granted the point, and pressed him about RG. Maloney was just getting warm, however. “We have a code of conduct that includes not casting anyone under 21 in our ads, and ensuring that the known audience of paid advertising is believed to be above 73 percent 21 [or older],” he told me. “We ban all university partnerships. We ban all agreements with NIL [Name, Image and Likeness] athletes. There’s no leafletting and pamphlet dropping on college campuses. None of those things are permitted.”

He went on like this for 15 minutes, laying out the Four Pillars of RG. “Stick to a budget. Bet legally [i.e., on their apps, not offshore sites]. Know the odds. And keep it fun. Do it in the company of others,” said Maloney. “This is not a wealth-creation exercise [or] an investment vehicle. This is entertainment.”

Since grade school, we’ve been trained to blame the addict for addiction: a failure of will and want-to in the weak. Even when the truth emerges, we still default to that warhorse, character, as the root of personal ruin. It’s only when the operators are forced to pay out fortunes that we finally fault the poisoner, not the poisoned. Hundreds of billions recovered from the tobacco companies, not counting the giant verdicts they keep losing. More than seven billion from the Sackler family. In America, the facts must defer to the funds. Our justice is a giant cardboard check.

No one knows that lesson better than Dick Daynard, the godfather of tobacco litigation. A Harvard-trained lawyer, he founded a pivotal nonprofit, the Tobacco Products Liability Project, as a young attorney in the Eighties. TPLP became the tip line and database for the lawyers, reporters, and confidential sources who finally beat Big Tobacco in the mid- to late-Nineties.

We’re sitting at a table in his offices in Boston, a quarter or so mile from Fenway Park. Joining us is Mark Gottlieb, Daynard’s voluble chief of staff, and the jet-lagged Harry Levant, just back from two symposia in Colorado. It was Levant who approached Daynard with his next crusade: suing the SBOs for the harms done to their users. Daynard, a laconic sort who wouldn’t order a hot dog without due process, tasked his staff to study the matter closely. “The doom loop of addiction?” says Gottlieb. “The losses that last till the customer drops? It wasn’t a tough decision to go forward.”

Harry Levant is a longtime foe of the SBOs: “Among the dangers of celebrity endorsements is the normalization of an addictive product.”

Thato Dadson/Courtesy of Harry Levant

Through TPLP’s successor, the Public Health Advocacy Institute, Daynard’s team brought the first sports-bet lawsuit in Massachusetts in 2023. They picked DraftKings as their opening-round opponent. The complaint they filed was a strategic one: a tautly focused claim of consumer fraud. “Plaintiffs allege that the offer of the $1,000 bonus … was and is unfair and deceptive because, among other things, a new customer would, in order to get a $1,000 bonus, actually need to deposit five times that amount and then, within 90 days, place $25,000 in bets with only certain odds of return,” the suit reads. “In other words, the ‘$1,000 Bonus’ is structured so that it is inordinately expensive to obtain $1,000, and the new user is, instead, statistically likely to lose money by chasing the bonus.”

“In what world would anyone call that ‘responsible gaming’?” Daynard says.

He filed the case, a class action, in Massachusetts, a state with stringent consumer-protection laws. DraftKings, for its part, filed a motion to dismiss. Its argument? “No reasonable consumer would have understood the Promotion in the terms that Plaintiffs allege.” That pleading was roundly denied by the judge; last summer, the case proceeded to discovery. Barring a settlement, the case heads to trial in two years. Meantime, Daynard’s colleagues are scouring DraftKings’ files, combing through tranches of court-compelled data to see if they can prove that DraftKings’ allegedly fraudulent ads are “deceptive to its target customers,” per the suit. To be clear: Gottlieb et al. aren’t bucking for prohibition. Legal gambling is here to stay, and they’re … OK with that. “Abolishing it at this point is DOA; there’s too much critical mass to take it down,” says Levant, who recently moved to Boston as the gambling-policy director of PHAI. “All we ask for are common-sense changes to the way these outfits do business.”

For a list of those changes, I spoke to John Keenan, a reformer in the Massachusetts Senate. Keenan’s seen this rodeo before: He chaired the Senate’s Joint Committee on Mental Health and Substance Abuse through the last two waves of the opioids crisis. “When you look at Purdue Pharma, what did they have? A new product they hawked relentlessly — and often falsely,” says Keenan. Same difference with Big Sports Bet, except “their marketing’s an onslaught: They’ve rewritten the book on selling addictive products.”

So Keenan’s sponsored a bill called the Bettor Health Act. Besides raising the state-tax rate on SBOs from 20 to 51 percent, it would instantly ban all sports-bet ads during live, in-game broadcasts. Further, it would outlaw player props, i.e., a parlay on Steph Curry to hit more than four threes and exceed eight assists against the Lakers. (Keenan calls those bets “the crack cocaine” of gambling.) The bill would also slap affordability checks on the SBOs: “If [someone] bets more than $1,000 a day, the industry has to check [his] bank account” to be sure he can support that action, says Keenan.

But maybe the best thing Keenan’s bill would do is force the apps to share their data with the state. “If there’s college kids jumping out of windows now, we need to see those accounts to figure out why. We have a moral obligation to those kids and their families. Otherwise, we’ll lose a generation.”

IT’S BEEN MORE THAN A YEAR now since Andrew placed a bet — but he’ll be the first to admit he’s been here before. “I quit cold turkey in 2020,” he says, “when my girlfriend found out she was pregnant.” Months of sobriety later, he rented a U-Haul and trucked their joint possessions to Pennsylvania. But driving across the line into Delaware — the first state, by a nose, to approve the apps — Andrew was beset by FanDuel radio ads and billboards. That night, he opened an account, grabbed the welcome bonus, and promptly lost his mind for four years.

“The guy I became — I don’t know who that was,” he says. Depressed and withdrawn, “always snapping at my girl; all I wanted to do was go and hide.” He holed up in the spare room of the place they’d rented, betting like he’d never bet in Georgia. “Those offshore apps — yeah, I liked my parlays, but they just had the basics,” meaning money line, point spread, over/under. But FanDuel? “FanDuel was fuckin’ Disneyland, man. You could build your own parlay off a thousand different props — and the crazier the props, the bigger the payout.” That, he hastens to add, is how to tell you’re an addict: “We only play the long shots. Longer, the better.”

Seven months after the couple moved north, Andrew’s girlfriend left him and took their three-month-olds with her. Andrew hasn’t seen his kids, now four, since; he relinquished his parental rights during that four-year spiral, failing to appear at visitations. Though he’s stable enough now to send her child support, he hasn’t pushed his ex for visitation. “I have no moral ground to be in their lives,” he says. “I burned every bridge and ruined every trust with everyone I ever knew. At this point, it’s just about living my life and trying to prove I can do better.”

Though we’re speaking by phone, I sense his mood straying, drawn to the shadows of the past. There’s a species of forgetting when you’ve lived apart, a gap that can’t be filled by stepping back into the world. Of all the sunk assets, faith is the dearest: faith that you still matter out there, and still share a language with other people. To reclaim that faith, Andrew’s gone public with his story, telling it to anyone who’ll listen. He’s appeared, under his own name, on CNN and CBS; spent hours on the phone with me to be sure I get it all; and made himself available to the people he hurt, giving a ruthless accounting of his sins. He has no expectation that the truth will set him free, or serve as recompense for the past.

“I’m just putting this out there [in hopes] that someone hears it and does something before a bunch of people die. The way these companies play you, chase and harass you till you’re worse than broke and get to thinking, ‘Maybe it would be better if I was gone.’”

Continue Reading

-

Thanks to AI, Our Faces No Longer Belong to Us – The Wall Street Journal

- Thanks to AI, Our Faces No Longer Belong to Us The Wall Street Journal

- AI-pocalypse Now: The New Identity Thieves The Times of India

- Selling ourselves, pixel by pixel: The real risk of Gemini’s 3D images EastMojo

- AI Just Crossed the Line – How…

Continue Reading

-

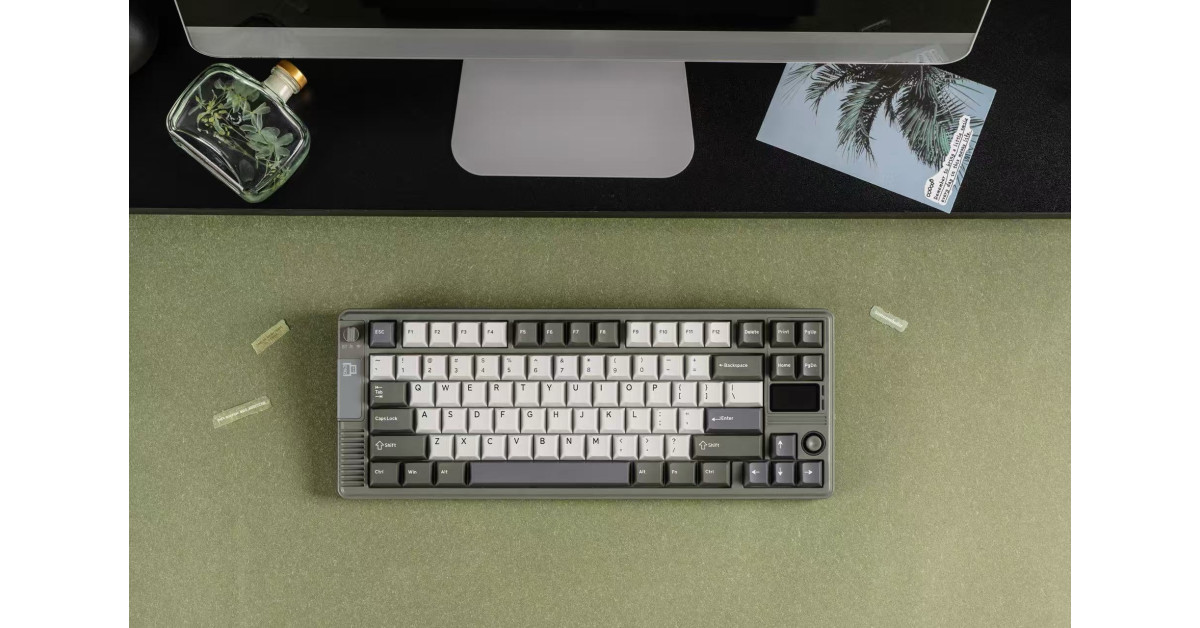

Epomaker Launches the RT85 Keyboard: Where Vintage Aesthetics Meet Modern Innovation

Building on the acclaim of the RT100 and its engaging secondary display, Epomaker is proud to announce the Epomaker RT85, the latest addition to the RT series.

NEW…Continue Reading

-

6 lightweight self-hosted apps you can run on basically any NAS

Being able to self-host your own services is one of the best aspects of owning a home server. Not only do these FOSS tools spare your wallet from regular subscriptions, but they also prevent third-party firms from gaining access to your private…

Continue Reading