Guest Editors

Justin Matthew Losciale, DPT, SCS, PhD, University of British Columbia, Canada

Ramana Piussi, PhD, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

Submission Status: Open | Submission Deadline: 15 July 2026

BMC…

Justin Matthew Losciale, DPT, SCS, PhD, University of British Columbia, Canada

Ramana Piussi, PhD, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

BMC…

Thelma Escobar, an assistant professor of biochemistry at the University of Washington, presented at the Hopkins Department of Biology’s Seminar Series on Thursday, Sept. 25, 2025. She discussed the progress her lab has…

A free agent signee, Kevon Looney was among the Pelicans’ key offseason additions.

METAIRIE, La. (AP) — New Orleans Pelicans center Kevon Looney has been diagnosed with a left knee injury that is expected to sideline him for at least two to…

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate…

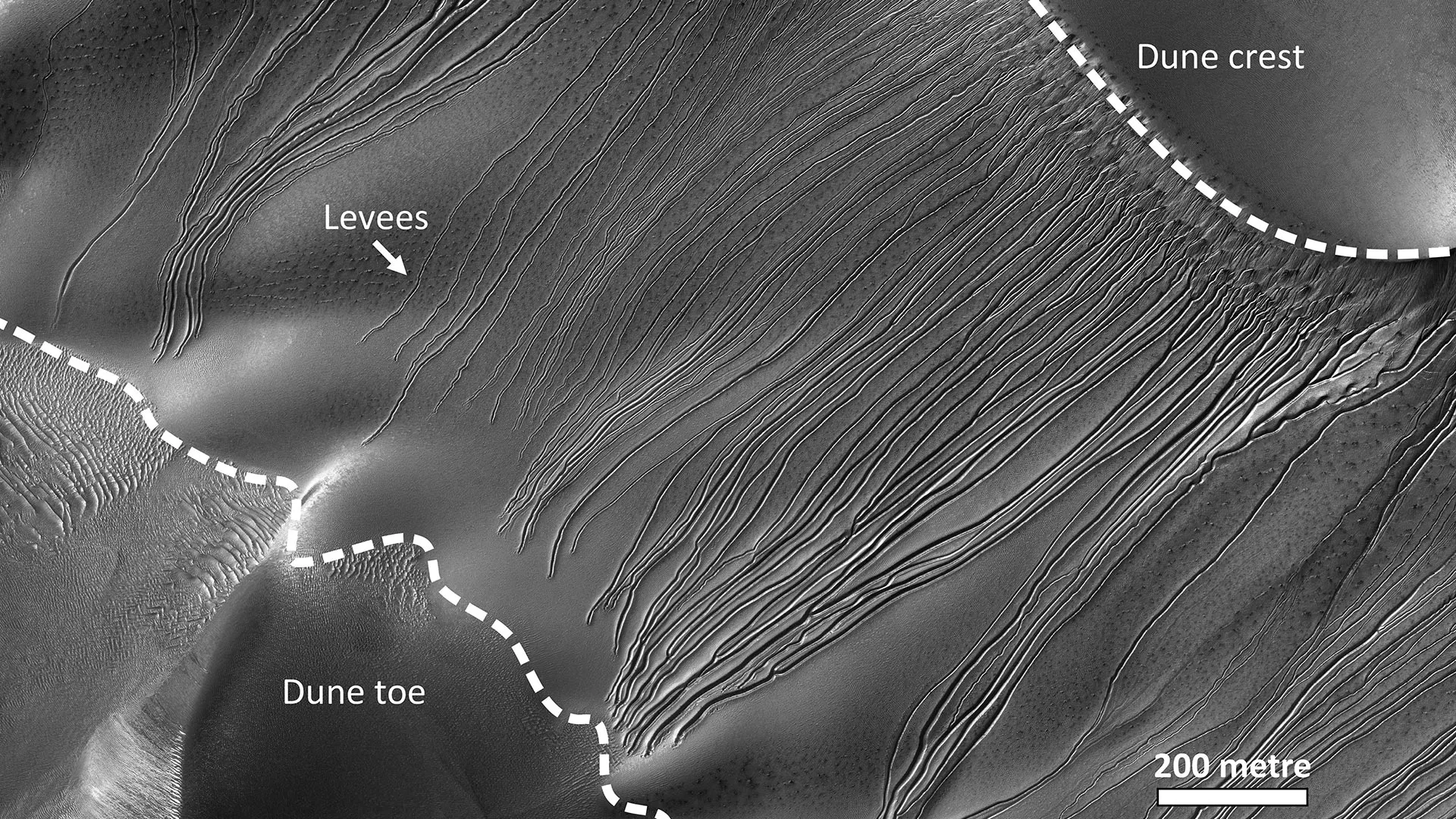

Could Mars have once supported life? Scientists still don’t have proof. Yet some of the planet’s strange surface features might seem to hint at it. Earth scientist Dr. Lonneke Roelofs of Utrecht University set out to study the origin of…

Terms

While we only use edited and approved content for Azthena

answers, it may on occasions provide incorrect responses.

Please confirm any data provided with the related suppliers or

…

Although cannabis research has been outpaced by consumer

behavior and public policy, the research is catching up. A growing

body of medical studies link cannabis exposure to cardiovascular

harms that can include heart attack, stroke, heart…

A state-of-the-art health screening van launched this month is bringing advanced imaging technology and health education directly to New Yorkers who are at the greatest risk of developing lung cancer. The initiative — a…

TOKYO – Nikon Corporation (Nikon) is pleased to announce the release of the NIKKOR Z DX MC 35mm f/1.7, a standard micro lens for APS-C size/DX-format mirrorless cameras.

The NIKKOR Z DX MC 35mm f/1.7 is a fast, lightweight standard micro…

Ian Falconer kept thinking about the heaps of discarded plastic fishing nets he saw at Newlyn harbour near his home in Cornwall. “I thought ‘it’s such a waste’,” he says. “There has to be a better solution than it all going into landfill.”

Falconer, 52, who studied environmental and mining geology at university, came up with a plan: shredding and cleaning the worn out nets, melting the plastic down and converting it into filament to be used in 3D printing. He then built a “micro-factory” so that the filament could be made into useful stuff.

“Every year, up to 1m tonnes of fishing nets are discarded,” he says. “Most of that ends up in landfill or is burned, or worse still finds its way back into the oceans. This showed there was another way for some of that material.”

The first big challenge he encountered when he started in 2016, was getting hold of the nets. But he badgered the Newlyn harbour master into giving him a few to test his theory in his kitchen.

Since its launch the following year, Falconer’s company OrCA (previously Fishy Filaments) has raised more than £1m from small investors in over 40 countries. The investment funded the development of patented new machinery that can convert more than 20 kilos of nylon fishing nets an hour. He claims the recycling process has less than 3% of the carbon impact of producing new nylon.

“When they get to us, this particular type of fishing nets have typically been used by Cornish fishers for around six months,” he says. “They are routinely swapped out because their surfaces become cloudy due to wear and the build up of an algal biofilm. With time and repeated use, eventually the fish can sense them in the water and avoid them.

“Skippers can see their catches fall as their nets age and it makes sense to replace them.”

The nets that go into the shredder come out as small blue-green beads that Falconer sells to 3D printing companies, which convert them into strings of filament used in 3D printing. They also get sold around the world to replace new plastic in more conventional products that are made using injection moulding.

Falconer’s shipping container office is full of items made from the raw material: sunglasses, light shades, bottle openers, razor blade handles. It can be used for just about anything. The items he is most proud of are those made from his nylon mixed with waste carbon fibre – mostly from offcuts of car and aeroplane manufacturing. This stronger and more expensive product is used to make parts for racing bikes and super-light sunglasses, and industrial components such as electronic enclosures.

The carbon and nylon mix sells for up to £35,000 a tonne – more than the £12,000 a tonne pure nylon beads. “Our process turns a liability of about £500 a tonne to pay to get someone to take the nets away, not to mention the environmental cost of that, into something of real value,” Falconer says. “Now, when I pass the piles of fishing nets on the harbourside, I see piles of money.”

Abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear poses one of the most serious threats to marine life, says Rachel Coppock, marine ecologist at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory, adding that innovative ideas to reduce this are welcome.

“Recycling schemes are increasingly seen as viable and beneficial in demonstrating how old gear can be transformed into new products, reducing landfill waste and supporting a circular economy,” she says. “Though challenges remain in scaling these efforts due to material complexity and infrastructure gaps.”

Falconer’s roster of clients, which includes Philips lighting, L’Oréal, Ford and Mercedes-Benz, is increasing as more companies see OrCA’s potential to help them reduce their carbon footprint by increasing the proportion of their products made from recycled materials.

“The European Union wants automakers to use at least 20% recycled plastic by 2035,” he says. “Using ours is one of the easiest ways to do it.”

Falconer could make a nice living continuing to recycle Newlyn fishers’ nets, but he has wider ambitions. “Waste fishing nets are a problem here in Cornwall, but the same type of nets are a much bigger problem in other countries, especially those without established waste systems,” he says. “Around Africa, South and Central America and Asia you see these nets littering beaches.”

Many of those countries don’t have the equipment to recycle the nets, he says, so they are burned or just left as waste. “They even end up back in the water where they can damage coral reefs and harm marine life, including the fisheries that the local communities rely on for food.”

About 150,000 tonnes of nylon monofilament fishing nets are made every year, and, based on external reports, Falconer estimates production will soon rise to 200,000 tonnes. The world’s total traditional nylon recycling capacity is less than 150,000 tonnes a year, so less than half the capacity that European carmakers need to meet their targets, and almost all of that is taken up with recycling carpets and other textiles.

To try to combat the problem, Falconer plans on exporting his recycling solution to any harbour that wants it. A container with all the equipment needed to run a mini recycling plant would cost about $500,000 (£370,000) if built in the UK.

Falconer says he has already received inquiries from 14 countries including Brazil, Colombia, Ghana, South Africa and Vietnam.

“The beauty of it is that it all fits in a shipping container and pretty much anyone can operate it,” he says. “So you could have one of these at every harbour around the world, converting a costly and hazardous waste into a profitable raw material.”