Giannis Antetokounmpo: ‘I’ve always wanted to be in Milwaukee, always wanted to represent the city, as long as we have the opportunity to win.’

MILWAUKEE (AP) — Giannis Antetokounmpo reaffirmed that he’s “locked in” with the…

Giannis Antetokounmpo: ‘I’ve always wanted to be in Milwaukee, always wanted to represent the city, as long as we have the opportunity to win.’

MILWAUKEE (AP) — Giannis Antetokounmpo reaffirmed that he’s “locked in” with the…

Sophie CridlandSouth of England

BBC

BBCYoung people have said the social pressure to have a smartphone has made them “almost essential”.

In February 2024, Ofcom reported that nine out of 10…

Christening and Launch Ceremony of HAMANASU

Tokyo, October 9, 2025 – Mitsubishi Shipbuilding Co., Ltd., a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) Group, held a christening and launch ceremony on October 9 for the second of two large car ferries ordered by Shinnihonkai Ferry Co., Ltd. and Japan Railway Construction, Transport and Technology Agency (JRTT). The ceremony took place at the Enoura Plant of MHI’s Shimonoseki Shipyard & Machinery Works in Yamaguchi Prefecture. The new ferry will serve on a shipping route between the cities of Otaru in Hokkaido and Maizuru in Kyoto Prefecture.

At the ceremony, Shinnihonkai Ferry President Yasuo Iritani christened the new ferry “HAMANASU,” the Japanese word for a species of native shrub rose. The ceremonial rope cut was performed by Nozomi Kobayashi, ship travel ambassador for the Japan Passengerboat Association. The ship’s handover is scheduled for June 2026 following completion of outfitting work and sea trials. The HAMANASU is the tenth ferry built by Mitsubishi Shipbuilding for Shinnihonkai Ferry.

The HAMANASU utilizes the latest energy-saving vessel design, including being one of the second ferries in Japan to incorporate a buttock-flow stern hull(Note1) and a ducktail,(Note2) along with a KATANA BOW. Propulsion resistance is suppressed by an energy-saving roll-damping system combining an anti-rolling tank(Note3) and fin stabilizers,(Note4) providing energy savings of 5% compared to conventional ships.

The christening and launch ceremony for the first ship ordered by Shinnihonkai Ferry and JRTT, named KEYAKI, was held in April 2025, with handover scheduled for November.

Japan is currently undergoing a modal shift to sea transport to mitigate environmental impacts by reducing CO2 emissions, and to compensate for truck driver shortages arising from workstyle reforms. This shift has brought utilization of ferry transport into sharp relief. Going forward, Mitsubishi Shipbuilding will continue to contribute to the active use of sea transport and environmental protection, resolving diverse issues together with its business partners through construction of ferries that provide stable sea transport together with outstanding energy and environmental performance.

■ Main Specifications of the HAMANASU

| Ship type | Passenger-carrying car ferry |

|---|---|

| LOA | Approx. 199m |

| Beam | Approx. 25.5m |

| Gross tonnage | Approx. 14,300t |

| Service speed | Approx. 28.3 knots |

| Passenger capacity | 286 |

| Loading capacity | Approx. 150 trucks and 30 passenger cars |

9 October 2025

What benefits would consumers and end users get from the introduction of the digital euro?

The core issue is that the world is changing, and people are increasingly paying digitally. But because cash cannot be used for digital payments, this reduces their freedom of choice. We want to preserve this freedom by complementing physical cash with a digital equivalent – a digital euro. This would ensure that people enjoy the benefits of cash in the digital era.

Cash has key advantages. It is Europeans’ money, issued by their central bank. It is the most widely accepted and inclusive payment solution; and the one that best preserves our privacy. But its role is declining because we cannot use it for digital payments.

In today’s world, if we do not provide people with a digital equivalent to cash, we constrain their freedom. Let me give you an example. You cannot use cash for e-commerce, which already accounts for one-third of our day-to-day transactions in the euro area. Now, imagine that e-commerce continues to expand – without a digital public means of payment, people are left with no choice but to use private payment solutions. This is a fundamental problem for a central bank, because we have a mandate to provide people with a public means of payment for their day-to-day purchases.

This has very concrete implications for Europeans.

Consumers are eager to shop, not to deal with the hassle of paying – they need a payment solution that is simple, fast, secure and easy. Do we have a solution today that provides for this? I don’t think so. In Italy, if I want to go and buy something in a shop, I can use a piece of plastic: a debit card issued by my local bank. But that piece of plastic may not work in all shops, and it may not work when I shop online or when I’m in Germany. And it doesn’t allow me to make peer-to-peer payments. To cater for all of these use cases, I need several different solutions. This is inefficient and inconvenient for users.

We do not currently have one single, simple, digital means of payment that we can use to pay across Europe, be it in shops, online or from person to person. And the question that follows from this is: if we provide such a means of payment, have we improved the lives of people in Europe? It seems to me that the answer is yes.

The main reason for the digital euro is to allow people to make digital payments anywhere in Europe. We want to ensure that we Europeans can use our money, the euro, whenever we need it.

Another key reason is to reduce our over-reliance on non-European solutions, which currently limits competition and results in higher fees for merchants – and ultimately, higher prices for consumers. It also makes us vulnerable: we depend on others for our money and this can be weaponised against us. Ten years ago we weren’t facing this problem, because cash was king. We did depend on foreign companies for digital payments, but it was not critical. Today, two-thirds of euro area countries lack a domestic card payment solution, and all of them rely on international card schemes for payments to other euro area countries. Non-European solutions also dominate online payments, and with e‑commerce rapidly expanding, this dependency is only increasing.

At the same time, in some places, the infrastructure supporting cash payments is shrinking. I’ll give you an example. I was in Amsterdam a couple of weeks ago and I went to the supermarket. There were ten card-only self-service checkouts and just one cashier for cash payments. To pay with cash, there was a long queue. This creates a disincentive to use cash.

Europe’s lack of a unified digital payment solution is working against us, in the sense that the expansion of the e-commerce space is pushing us to be more and more dependent on solutions that we don’t have any control over.

As citizens, we should care that at any moment, our means of payment can be interrupted at the will of somebody outside Europe. And as consumers, we should also care that merchants face higher fees owing to the lack of sufficient alternatives, as we too pay for it in the end in the form of higher prices.

A digital euro would complement cash as its digital counterpart. It would offer a European solution built on European infrastructure, increasing the options available to Europeans and preserving their freedom when it comes to payments.

What are the use cases that the digital euro is supposed to cover that banks and other services are not covering today?

This very much depends from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, Estonia doesn’t have a domestic card payment solution or digital wallet. For most use cases, you have to use a non‑European solution, except when using cash.

So where are we strong? European domestic solutions excel in certain areas, particularly at the point of sale through traditional cards. And this holds true in countries like France or Italy. However, even in those cases, domestic cards cannot be used in other countries, leading to a reliance on international card schemes for cross-border transactions.

There is also very little coverage for e-commerce. Only two euro area countries – Spain and the Netherlands – offer domestic online payment solutions, namely Bizum and iDEAL. By contrast, in Germany, most online transactions are done through PayPal rather than a domestic solution. Wero still needs to enter that space.

The digital euro would cover all key use cases: point of sale, e-commerce, peer-to-peer and even payments to or from the Government. Users would have a universal means of payment that satisfies all legal obligations and is guaranteed to be accepted wherever digital payments are possible. In this sense, the digital euro serves as a digital counterpart to cash.

Can you tell us a little bit more about how it will work, how people will get it and how they can use it?

It will work like any other means of payment. People will access the digital euro through their bank or a payment service provider of their choice. The bank or payment service provider will act as the intermediary, onboarding clients and handling processes such as anti-money laundering checks, and so forth. Users will receive either an electronic wallet or a card that allows them to access and use the digital euro. From there, the system will function much like any other payment method.

However, there’s more to it. Banks could also embed the digital euro app directly in their existing wallets. For you as a consumer, it will be no different if the transaction is going through commercial bank money or the digital euro wallet. What is important is that – with one simple, single app on your phone, in that case your bank app – you can pay everywhere in Europe. That’s the fundamental advantage.

There will be two ways to pay with the digital euro.

First, you can transfer money from your bank account into the wallet and then pay.

Alternatively, you can link your digital euro wallet to your bank account. In that case, you don’t even need to have funds in your digital euro wallet before you pay. Let’s say I’m out shopping and find a pair of shoes that cost €150. Even if I don’t have €150 in my digital euro wallet, I can still make the purchase. The digital euro app will automatically connect with my bank account, transfer the required amount into my digital euro wallet, and complete the payment seemlessly and instantaneously.

The digital euro will also offer an important functionality: offline payments. Imagine I’m going to a pharmacy and I don’t want anybody to know that I’m going to buy something there – I could decide to pay with the offline solution. To do so, I simply need to prefund my offline wallet, go to the pharmacy, buy whatever I want, and nobody will know about this transaction except me and the pharmacy. The offline solution will be very convenient not just in terms of privacy, but also resilience: it will ensure we can still pay even when there is an outage, or simply when there is no network connection.

The promise is that the digital euro will offer a high level of privacy, like you mention. But on the other hand, people are fearing that it’ll be the opposite – that Big Brother will be looking at your transaction data, etc. So, who exactly will have access to the transaction data? Could there be cases where the ECB, the Government or police have access to this data?

The offline solution will be completely anonymous. Only the payer and the payee will know about their payments because there will be no record of the transaction. So this is as private as cash. Money moves from one wallet to another but the details of the transactions will not be known to anyone else. To address anti-money laundering concerns, offline transactions may be subject to a maximum amount. This will be for the legislators to decide.

Let me now explain how privacy will work for online payments. There are three pillars to protecting privacy for online payments.

The first pillar is technology. When you initiate a payment, the bank will send three pieces of information to the ECB: the amount, a code representing the payer and a code representing the payee. The codes for the payer and payee are encrypted. The ECB does not know who they are. Only the payer’s bank can link the code with the the payer’s identity. This is the same for the payee; only the payee’s bank knows the payee’s identity. Checks for possible illicit activities such as money laundering or terrorist financing will take place at the level of the commercial bank, as is currently the case for online transactions.

The second pillar is regulation. We are working on very strict rules on who will be able to access those three pieces of information for the purpose of running the system. And we’ll make sure this can be audited. We will be supervised by independent data protection authorities to ensure that we comply with EU data protection law. We want them to see what we are doing and we want to make sure that everybody knows that we walk the talk. There will be complete transparency.

The third pillar is openness to future privacy-enhancing technologies. Privacy technology is constantly evolving, and we are in touch with innovators around the world, especially the BIS Innovation Hub, to explore these new, more sophisticated technologies and potentially implement them in the future.

So, in summary, we will ensure privacy through technology, regulation and being open to future privacy-enhancing techniques so that we can bring an additional layer of privacy as soon as more advanced technologies are ready to be implemented in a system that has to run a billion transactions every day.

What is the current status of the digital euro project? And are there major obstacles that you are now facing, such as resistance from banks or other market players?

Internally, we are completely on schedule with the technical work. We have a timeline and we are fully respecting it. But as we have previously said, we will not issue the digital euro until we have the legislation in place. So we are waiting for this legislation to be adopted.

The European Commission presented its legislative proposal for the digital euro on 28 June 2023. That was over two years ago. The proposal is now being examined by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU – which brings together national finance ministers – so that they can suggest any amendments they may wish to make. Once both institutions have agreed on their position, they will meet with the European Commission and decide on the final legislation. The discussion in the EU Council is proceeding very well. The current Danish Presidency of the EU Council is committed to reaching an agreement by the end of the year. In September an important agreement was reached on how to set the holding limit. Member States are now discussing the compensation model, i.e. how all parties involved will be compensated for their respective roles. They are paying close attention to the issue of privacy, which is a very important matter. To me, the compensation model is more of a political matter than a technical one, and the EU Council is working on this. The Council Presidency is very confident that the EU Council will finalise its position – what they call the “general approach” – by the end of the year.

At the European Parliament, the rapporteur has publicly said that he will publish his proposal by 24 October. Members of the European Parliament then have five to six weeks to present amendments and almost five months to discuss them. The European Parliament will possibly finalise their position at the beginning of May, which means that they will start discussions with the EU Council afterwards to agree on a common text. It might take three months or six months, but we should have the legislation in place in the second half of 2026.

From what I understand, there are differences of opinion within the European Parliament. But Members of Parliament are no longer discussing if the digital euro should be introduced; they are discussing how. It’s important for the success of the digital euro that they exercise their democratic role in full.

Banks have two concerns. One is cost and the other is the risk of disintermediation. We have explained many times that both are a little overstated and that safeguards have been foreseen that can be further discussed.

What are the incentives for banks to play their part in implementing the digital euro so that people will start using it?

Banks can make money out of this. Simply put, banks will be remunerated for the services that they provide to people.

Who will pay? The ECB?

The compensation model will be similar to the one that currently applies to private digital payment solutions, but both banks and merchants stand to benefit.

Today, there are four parties involved in a card payment: the issuing bank (the bank that issues the card); the acquiring bank (the merchant’s bank); the merchant; and the infrastructure provider. When a payment takes place, the merchant pays what is called a “merchant service charge” to the acquiring bank for processing the payment, and part of this charge is passed on to the issuing bank as an “interchange fee”. Both the acquiring and issuing banks also have to pay “scheme fees” and other charges to the payment scheme and infrastructure providers, which typically are international card schemes.

How will this work with the digital euro? We will not charge scheme fees, nor will we charge for the use of our infrastructure. So money will be saved in the process. The idea is that the money that is saved will be transferred in part to the merchants (who will pay lower fees) and in part to the acquiring and issuing banks on top of their current remuneration.

So Visa and MasterCard will be cut out of the process?

Visa and MasterCard will be remunerated according to their fee structure whenever people chose to use these payment solutions. If people decide to pay with the digital euro, the scheme that I have just described will be applied. We are not forcing people to pay with the digital euro, but they can if they choose to.

Has there been a lot of intensive lobbying from Visa and Mastercard?

Understandably – they are business people. But they can reduce costs and compete. They also offer insurance and other quality services. The bottom line is: people should decide. We are not here to exclude anybody. We are here to make the system more resilient.

And in your opinion, is that a key reason why the digital euro could be widely adopted or is there another reason?

Merchants will encourage clients to pay with the digital euro. Why?

First, merchants will pay less.

Second, they will gain negotiation power as there’ll be an alternative to international card schemes. Merchants will be able to say: “if you don’t want to reduce merchant fees, I’m going to use the digital euro”.

There is one additional reason: standards. If you are a merchant that operates in many markets in Europe, you have to accept many different payment solutions. For example, imagine you are a large supermarket chain operating in Estonia, France, Spain, etc. You must be able to accept all the domestic payment solutions in those countries. And each of these solutions has its own standards. So you have a huge technical complexity to deal with. A digital euro standard that the various solutions could use across Europe would be a huge simplification and would result in lower costs.

To recap, there are three key benefits for merchants: reduced fees, more negotiating power with regard to card schemes and simplification on the back-end side and on the operational side.

You mentioned inclusion. Many people, particularly older people, prefer to use cash. So people are also wondering: is the digital euro the next step towards eliminating cash?

This is completely against our philosophy.

Physical cash is central bank money. We certainly do not want to eliminate a key form of the money that we issue, one that many people remain attached to.

And we are not just saying this. There are facts that prove this.

First, we are investing in a new series of banknotes. We just launched a design contest for this purpose.

Second, a discussion is taking place on a proposed EU legislation to strengthen the legal tender of cash. We are pushing to strengthen it even further: we are the strongest voice in asking to reduce exceptions to the obligation to accept cash. The ECB has been very vocal on this topic.

Our job is to provide people with means of payment – that is in our mandate. People want to use cash and we will continue to provide cash. But they also want to be able to pay digitally. So to fulfill that same mandate, we are working on the digital euro. The digital euro will complement physical cash by offering a digital form of cash.

We are not here to tell people how they should pay. It’s their money and their choice. We are a technical implementing agency, tasked with fulfilling the needs of Europeans. I want to make that clear. We have neither the power nor the mandate to decide how people should pay. But we have a responsibility to continue offering the option of paying with sovereign money.

We do not want to replace cash. We want cash to exist in a physical form and digital form so that cash can continue to thrive in the digital era.

Handout

Handout“I feel very proud,” said Raymond James, as he prepared to walk on to the pitch at Wembley as a footballer’s…

DAKAR, Senegal — An Ebola outbreak that has plagued southern Congo in recent weeks is starting to be contained, the World Health Organization said Wednesday, with no new cases reported since the U.N. health agency’s last update on Oct. 1.

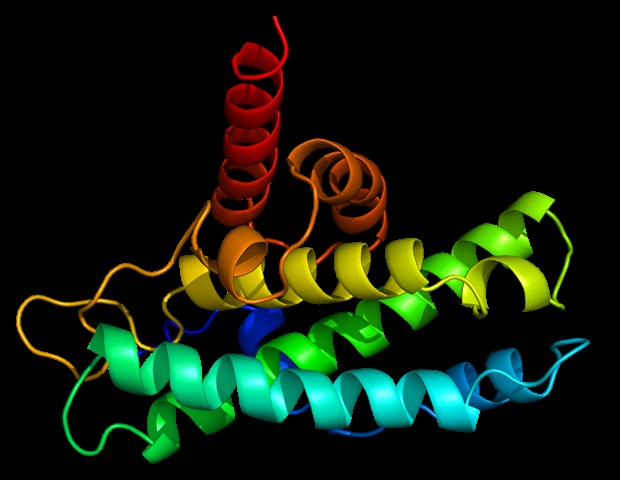

Stress granules are droplet-like protein hubs that temporarily shield fragile RNA from cellular stresses such as toxins. VCP is a protein essential for breaking up stress granules and has been linked to neurodegenerative diseases….

Semantic dementia (SD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by impaired confrontation naming, receptive vocabulary deterioration and impaired single-word comprehension as core clinical manifestations. Individuals…