Introduction

The global prevalence of myopia is on the rise, with projections suggesting that nearly half of the world’s population will be affected by 2050.1 This trend indicates a surge not only in mild and moderate myopia but also in high…

The global prevalence of myopia is on the rise, with projections suggesting that nearly half of the world’s population will be affected by 2050.1 This trend indicates a surge not only in mild and moderate myopia but also in high…

Bonner Kunstverein is proud to present Durchdringung, the first institutional solo exhibition in Germany by artist, filmmaker, and poet P. Staff, on view October 11, 2025–February 1, 2026. The exhibition presents newly commissioned works…

“Wrong anatomy” and “unlucky” were the explanations Shala Miller received for her recurrent ovarian torsions. At the beginning of this year, the artist underwent her third emergency surgery. Desperate to understand why her insides decide…

Endometrial cancer (EC) is a malignant tumor originating from endometrial epithelial cells and is one of the three major malignant tumors related to the female reproductive system. EC is characterized by irregular vaginal bleeding…

When Mark Constantine, 73, started cosmetics brand Lush, he was still recovering from bankruptcy, despite the triumphant sale of his first venture to The Body Shop for £9mn in 1991.

Yet Lush, launched in 1995, is now a global group, renowned for its bath bombs, operating more than 850 shops worldwide with an annual turnover in 2024 of £703mn, according to the company’s latest accounts.

Constantine, the chief executive, and his wife Mo still own more than 50 per cent of the company, and are estimated to be worth £249mn, according to the latest Sunday Times Beauty Rich List — all the more remarkable for a man who was homeless in his teens.

His obsession with cosmetics was cemented as a young hairdresser. He started mixing shampoos in the 1970s alongside a small team, and pitched them to The Body Shop founder, the late Anita Roddick, who had just opened her second branch. She gave him his big break and their partnership over the coming decade laid the foundations for what would later become Lush.

Having vowed never to retire, Constantine still works from the same building in Poole, Dorset, where he launched Lush 30 years ago alongside his co-founders. “We’ve got more ideas now than we ever know what to do with,” he says. The self-proclaimed “hippy soapmaker” is also a notable philanthropist.

Born: July 21, 1952, Kingston, Surrey

Education: Weymouth Grammar School

Career: 1972: Apprentice hairdresser at Elizabeth Arden, Bond Street

1973: Trainee trichologist at The Ginger Group; later went freelance

1976: Founded Constantine & Weir

1991: Sold rights to the Body Shop

1991-1994: Worked full-time on Cosmetics to Go

1995: Co-founded Lush

Lives: Poole, Dorset, with wife Mo, who is also a Lush co-founder

Where did your business career begin? You didn’t start Lush until you were in your forties

I was still in my early twenties, making products in my bedroom, when The Body Shop started accepting my ideas. It was quite a power trip. It was a hell of an opportunity and I was so fortunate.

I learned a lot from Anita over the 15 years we worked together. She was dynamic and epitomised charisma. But we would argue constantly. If you didn’t argue back, Anita would think you hadn’t made much of an effort. Once she called me “unprofessional”, and I told her I’d prefer she called me a “wanker”. Five minutes later, a bunch of flowers arrived, with a note that just said — “Wanker”. That was the way we did business.

We were partners until 1991, when she bought the rights to our formulas for £9mn.

But I blew it all on my next company, Cosmetics To Go, within a few years. It was a mail order catalogue of beauty products (the non-compete agreement meant we could only sell via mail order). With Cosmetics To Go, we lost £1 every time we sent out an order, which was a problem because we were really popular. The one consolation was that all the products and inventions in that catalogue were ones that Anita had rejected, such as the bath bombs.

How did you recover from bankruptcy in January 1994?

I was quite ashamed of myself. I’d never felt so alone after going bankrupt. When I met the bankruptcy receiver and put my hand out to shake his, he wouldn’t take it. There was definitely shame. I would go through the back door of the shop because I just couldn’t face going through the front. I wanted to stay at home with a bag over my head.

I then had to figure out how I would turn things around. We had three mortgages, including our family home, a factory, and the Poole store/office, and three kids to support. I’d already had to sell another house in Swanage, Dorset, at a 50 per cent loss. That sale left us with £43,000 in cash. That was all we had left by the mid-1990s. So I used that money to start Lush.

Did you or your wife hesitate about putting money into another business after the bankruptcy?

Well, no one was going to employ me. I was unemployable. I hadn’t — and haven’t — been employed full-time by anyone else since 1973.

I do remember I had to persuade Mo and my other business partner, Liz Weir, that perhaps we should put what was left into something new. I don’t know what exactly my wife thought about me betting on another business. But we’d been together a long time, so I think she just knew what I was like. I’m just really into the game. We both are.

Saying that, my seven-year-old son at the time did corner me one day and asked: “Do you think you ought to get a proper job?” I had to explain to him that I thought I could market my skills better than in a “proper job”.

How do you feel about your wealth after your success with Lush?

I’m never very comfortable when the Sunday Times Rich List comes out, mainly because you never actually have the money. Everyone assumes you have all that cash, and you don’t — it’s the asset. I still live in the same house we bought 40 years ago.

Ultimately, wealth gives you a great opportunity to do a whole lot of things for others. That’s what I’m proud of. I was really touched by the kindness I experienced when I was homeless, living in a tent in a forest after being kicked out of the family home at 16. People invited me for dinner and let me stay. That’s always stuck with me.

What are your views on the government’s tax policy?

In general, I think wealthy people obsess too much about tax. They do all sorts of things that mess up their lives because it’ll save them some money. It just complicates your life to get caught up in moving, such as non-doms or sailing around in big yachts to avoid tax days.

Lots of people who read the FT will disagree with me but, personally, I believe in paying tax. I don’t like it — I do think it’s important, though.

Saying that, my opinion on tax policy from a business point of view is that you should concentrate on growth. Businesses can get distracted by worrying about tax instead of growth.

Family businesses are the backbone of this country. They don’t generate news though, so politicians don’t understand them. The government thinks business is just The City, which is basically the betting house.

But we just have to live with the government’s decisions on tax. I’m not going to move to Switzerland or anything because of tax. I’m just hoping to live long enough to see the next government come in.

Will you leave the business to your children?

My children have worked their butts off in this business for 20 years. So yes, I would like to leave it to them. Do I want to leave them a huge tax bill? Not particularly. But the plan is for our three children to inherit our shares.

I love spoiling people, including my kids. And family businesses, by their nature, involve some kind of nepotism. But at the same time, the kids are building skills and going through all the tough stuff you have to go through.

What’s your philosophy on business today?

The reality is that entrepreneurs aren’t balanced people. I’ve had to manage my mental health my whole life, including panic attacks and anxiety.

But I don’t like the image of business that TV portrays, such as The Apprentice or Dragons’ Den. I don’t like programmes where the jeopardy makes people cry. I don’t like the idea of needing to make a pitch in three minutes. Business can be done in beautiful ways — politely and kindly. That’s why I co-wrote The Poetry Business School. Poetry can teach you so much.

I now see a business coach each week. We’ll talk about weak spots, such as how my judgment of men isn’t so good. I’ve turned a blind eye to some people I shouldn’t have. On the flip side, I think working with women is a secret weapon. As soon as you listen to them, that’s when you start getting successful.

Fundamentally, I believe in capitalism, but motivation should be shared around. At Lush, we’re partly family-owned and partly staff-owned [all external investors were later bought out]. That feels better than one or two people, then selling and taking all the money.

We’ve also given away £100mn in charitable giving over the past three decades. Yes, profit is still more important than policy, but not by much.

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

EU ships could face having to travel more slowly and use more fuel than their Asian competitors because of Brussels’ failure to authorise an innovative paint for ship hulls that prevents barnacles becoming stuck by making them hyperactive.

Medetomidine has long been allowed for human and veterinary use as a sedative, but scientists in Sweden discovered it has the opposite effect on barnacles, which become temporarily excited when they come into contact with the substance and so cannot settle on a surface.

While each barnacle is small, a build-up of the crustaceans can vastly increase a ship’s drag in the water, increasing fuel consumption and carbon emissions.

I-tech, the start-up that patented the medetomidine biocide with 40mn krone ($4.3mn) of support from the Swedish government, estimates that if 10 per cent of a hull is covered with barnacles, fuel consumption increases by 40 per cent if the same speed is maintained.

Anti-fouling paints are also an important means of stopping invasive species travelling between continents. But although the EU itself has also funded I-tech, it has not approved its paint for use 16 years after the company first applied.

Magnus Jönsson, chief executive of I-tech, said the paint was “a non-lethal way of stopping the barnacles settling on the surface”.

I-tech applied for authorisation to the European Commission in 2009 for consideration under its biocidal products regulation. While medetomidine itself has received temporary approval, long bureaucratic processes and checks on the safety of the substance have meant it has not been approved for use in any biocide products.

The European Chemicals Agency last year recommended that the temporary approval of medetomidine be ended because it is “persistent, toxic, and identified as an endocrine disrupter”. Its opinion was largely based on a Norwegian study, which I-tech argues is flawed.

Member states are due to vote on its ongoing authorisation in the coming months, allowing the commission to take a decision early next year.

Despite the lack of approval for its products, I-tech has received €670,000 of funding from the EU and €1.3mn in conditional loans from the Swedish Energy Agency to scale up.

More than 90 per cent of its sales are made outside Europe. It has gained market share of about 50 per cent in Japan and South Korea, as well as a foothold in China, where it competes with traditional antifouling paints.

“Anti-fouling remains a serious challenge for international shipping . . . We need more antifouling options available on the European market and we should really welcome new products like this,” said a Norwegian shipping representative, who asked not to be named.

The commissions said it would “consider all elements and information, including from stakeholders, when making its decision” on the substance’s authorisation.

Two major reports on the EU’s waning economic competitiveness issued last year pointed to a failure to scale up domestic start-ups. The European Commission has vowed to improve the regulatory framework for start-ups and small businesses, and to simplify legislation for industry.

I-tech argues its product could help European ships cut emissions in line with the bloc’s ambitious climate goals. It says covering a ship’s hull with its antifouling paint can reduce carbon emissions by 15 per cent.

Didier Leroy, technical and regulatory affairs director at CEPE, the industry body for paint, printing ink and artists’ colours, said the EU had “such severe chemical legislation that they discourage investment and innovation”.

“If there is no more sufficiently efficient antifouling paint on the EU market then ships will not dry-dock any more for repair and maintenance and this will be done outside the EU,” he said, adding that this would harm other parts of the EU economy.

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

European listings are showing signs of a revival as a string of companies launch or prepare initial public offerings, giving hope to the region’s capital markets after a prolonged slowdown.

This week, security services company Verisure raised €3.2bn in the biggest European listing for three years, while prosthetics company Ottobock raised €700mn in Germany’s largest IPO this year.

Swedish digital bank Noba, German automotive company Aumovio, skin laser seller The Beauty Tech Group and classifieds business Swiss Marketplace Group have all listed in Europe in the past few weeks.

Several more flotations are being planned, including an IPO of €10bn German auto marketplace Mobile.de in Frankfurt, and London listings for tinned food company Princes Group and specialist UK lender Shawbrook.

Company executives and their advisers say geopolitical and economic worries — including market jitters sparked by US tariffs — have eased somewhat, creating a more favourable environment for listings after several IPOs were put on hold.

Stock markets are also trading at record highs, giving further encouragement for companies to list.

“We’re breaking the deadlock,” said Richard Cormack, head of Emea equity capital markets at Goldman Sachs, adding that there was a “good-sized cohort of transactions . . . It feels like now we’re at the proper start of a cycle.”

Martin Thorneycroft, global co-head of equity capital markets at Morgan Stanley, said Verisure’s blockbuster listing “will give a big boost to the large-cap, high-quality assets in the pipeline”.

European stock exchanges have been struggling to attract new listings: there have been 76 so far this year, the lowest level since 2009, according to Dealogic data.

Private equity firms have held on to companies for longer, rather than bringing them to the market, in the face of subdued demand, while some businesses, such as Swedish fintech Klarna, have chosen to list in the US, lured by higher valuations and deeper capital markets.

The lack of listings has triggered European policymakers to try to encourage more domestic investment in homegrown businesses and incentivise founders to list businesses in the region.

Companies listing on Sweden’s Nasdaq stock exchange have raised the most so far this year, at $6.7bn, according to Dealogic, while $1.2bn has been raised on the Frankfurt stock exchange, and the same amount on the Swiss SIX venue.

“It’s encouraging that activity is broadening beyond markets with strong domestic bases like Switzerland and Scandinavia”, said Stephane Gruffat, Deutsche Bank’s global head of equity capital markets syndicate. “We’re now seeing renewed demand in the UK, Germany and Spain — including [from] retail investors.”

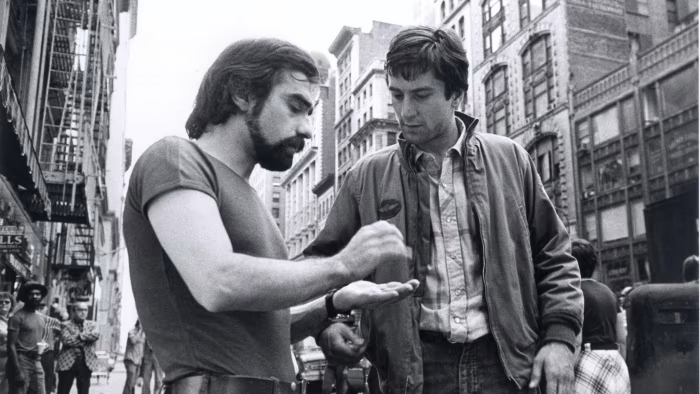

Martin Scorsese is fun. Even if you have never seen his films, you can see this on TikTok, where he now often stars in larky videos made by his youngest daughter, Francesca. A recent Scorsese production finds the pair appear in a skit inspired by…

Ben Meiselas is a very busy man. So busy, he has to break off halfway through our interview to conduct an interview of his own, for his next broadcast. It’s 7am Los Angeles time when we meet via video call, and Meiselas is already well into…

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a structural developmental anomaly with Non-cystic lesion characterized by a defect in the diaphragm that permits herniation of abdominal viscera into the thoracic cavity.1 The estimated…