James GallagherHealth and science correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSide effects of different antidepressants have been ranked for the first time, revealing huge differences between drugs.

Academics looked at the impact medications had on patients in the…

James GallagherHealth and science correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSide effects of different antidepressants have been ranked for the first time, revealing huge differences between drugs.

Academics looked at the impact medications had on patients in the…

Mount Fuji and the Shinjuku skyline in Tokyo, Japan, on Friday, Feb. 14, 2025. Photographer: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Asia-Pacific markets fell Wednesday as investors assessed trade data from Japan and its new government.

Japanese exports in September snapped four months of declines, climbing 4.2% year on year, as shipments to Asia saw robust growth, partially offsetting the drop in exports to the U.S.

Exports, however, missed analysts’ expectations of a 4.6% rise, according to median estimates in a Reuters poll of economists.

Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi and her new cabinet were sworn in on Tuesday, with her former rival in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s leadership race, Shinjiro Koizumi, named defense minister and Satsuki Katayama becoming Japan’s first female finance minister.

Japan’s Nikkei 225 was down 1.26%, leading losses in Asia, while the Topix index lost 0.18%. Shares of SoftBank plunged over 10%, building on their 0.26% drop on Tuesday. Shares had gained 8.5% on Monday.

On Tuesday, the Nikkei briefly set a new intraday record of 49,945.95, before retreating after Takaichi won the parliamentary vote to become Prime Minister.

South Korea’s Kospi index was down 0.26%, while the small-cap Kosdaq fell 0.25%. Shares of LG Chem soared as much as 10% after Palliser Capital urged the chemicals company to revamp its board and buy back shares, according to a Reuters report.

Australia’s S&P/ASX 200 started the day down 0.73%, pulling back from earlier gains on Tuesday after rare earth stocks briefly rallied on news of a U.S.-Australia critical minerals agreement.

Hong Kong Hang Seng index futures were at 25,919, lower than the last close of 26,027.55.

Indian markets are closed for a holiday.

Overnight in the U.S., the Dow Jones Industrial Average set a new closing record, boosted by strong earnings reports from companies such as Coca-Cola and 3M, while the S&P 500 was relatively unchanged.

The 30-stock index gained 0.47% to close at 46,924.74, and briefly topped 47,000 during the session.

The broad market S&P 500 closed just above the flatline at 6,735.35, while the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite lagged, falling 0.16% to 22,953.67.

—CNBC’s Sean Conlon and Pia Singh contributed to this report.

Faisal IslamEconomics editor

Faisal IslamEconomics editor BBC

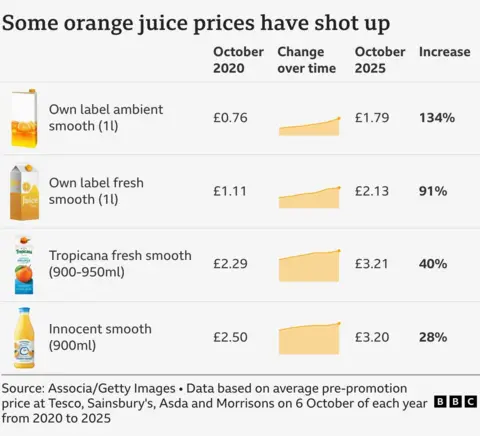

BBCThere has been more than a bitter twang in the glasses at British breakfast tables. Only five years ago, a typical supermarket own-label carton of orange juice could be bought for 76p for 1 litre. It now costs £1.79.

That’s a rise of 134% since 2020, and it’s up 29% just in the past year.

In cafes and restaurants it’s a similar story – with £3.50 to £4 now a standard price point for a glass of basic OJ.

One colleague was outraged to be sent a bill for £9 for a glass of hangover-busting orange juice and lemonade at an unassuming little restaurant in Kent. Asked why so much, she was told that the orange juice – albeit freshly squeezed – accounted for £5.30 of the price.

Yet as costs have surged, the taste is changing too, with certain manufacturers substituting oranges for mandarins to cut costs.

The public is, if you like, being freshly squeezed.

There are all sorts of reasons for this: disease among crops, extreme weather, over-reliance on supply from a single nation, new rules for packaging and complexities around trade wars and Brexit.

All of this is compounded by grocery price inflation which, after hitting 17.5% in 2023, came down (to around 5.7% in August) but is rising once again. New figures for overall inflation will be released later today.

It is a perfect storm.

Yet the problem is not isolated to orange juice – track the prices of all sorts of other groceries in supermarket aisles and you’ll see a similar pattern. And so understanding what has happened to orange juice offers a glimpse into how our overall grocery bills suddenly seem so expensive.

It all prompts the question: is this storm a passing one, or are prices set to remain stubbornly high – and should brace for them staying that way permanently?

Where else to start but in the orange groves of Florida where the industrialisation of OJ began as an initiative of the US Army during World War Two.

The US government was seeking a source of transportable Vitamin C for troops that didn’t taste like turpentine.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesOrange juice is nearly 90% water. So gently evaporating the water off the juice and freezing the concentrate, allowed for transportability of a much better tasting product when water was later re-added.

WW2 ended before the troops got to try it, but it ended up being commercialised by what became the American soft drink giant, Minute Maid.

It was popularised by Bing Crosby, who, as a significant shareholder, would sing in ads and radio show jingles about frozen orange juice being “better for your health”.

Western consumption of orange juice surged.

TV Times/ Getty Images/ Screen Archives

TV Times/ Getty Images/ Screen ArchivesFlash forward to today and an estimated 2.5 billion gallons of orange juice are drunk each year – with about a tenth of that in the UK, where the market is still growing.

At an industrial unit in the Essex town of Basildon, green steel drums of frozen orange concentrate arrive from Brazil, overseen by Maxim McDonald.

His firm Gerald McDonald and Co is named after his grandfather, a pioneer who was importing orange concentrate as far back as the 1940s from what was then British-mandate Palestine.

Today it produces juices and blends them, then sells them to supermarkets and restaurant suppliers.

But prices reached extraordinary heights in global markets, rising from $1(75p) to $1.50 (£1.12) per lb over the last decade, to a record $5.30 per lb by the end of last year.

This followed five years of poor crops, owing to severe drought and a disease called citrus greening (caused by a bacteria spread by insects). Brazil had its worst crop since 1988. In some parts of its citrus belt, two thirds of orange trees are affected.

“Around September of last year the price shot up to crazy levels,” Maxim tells me. “At the worst time I was being offered $7 a kilo.

“For such a major commodity to go from $2 to $7 is insane, but it took a while to filter through to consumers.”

Until 2023 the rise in orange juice prices was disguised among food inflation in general, explains Philip Coverdale, an industry expert at consultancy firm GlobalData.

Producers have tried to look beyond South America but it’s not easy – the supply of oranges has been sown up by Brazil, even more so than, say, the Saudis have cornered the market for crude oil.

Morocco, Egypt and South Africa grow oranges too but their supplies are more limited. Spain also grows them, but Valencia and Seville oranges are mostly exported as fruit, rather than concentrate. (Plus Spain too suffered from weather-related production slumps, including the floods in Valencia last October.)

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesEven within Brazil the market is concentrated in the hands of huge industrialised conglomerates.

In a truly competitive market the price would settle again – but it hasn’t, nor does the industry expect it to. This is a phenomenon that is common to many other ordinary groceries too whose prices have risen.

Florida is the other traditional exporter of oranges, but output from the Sunshine State over the past year has been the lowest since the Great Depression, amid a high number of hurricanes and long-term problems caused by citrus greening.

One problem with greening is that it reduces sugar content, making oranges less sweet.

“Not many are buying Florida oranges any more unless it is a requirement to label the juice ‘Florida Orange’,” says Maxim McDonald.

“It’s very difficult to get oranges out of Florida [because of the shortages] and it’s too expensive.”

VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesOne of the leading suppliers to Tropicana sold off some of its land earlier this year to build homes.

Tropicana itself, the marquee US brand for orange juice, had to restructure its debts this year. Pepsi has also sold most of its stake in it.

One of Tropicana’s recent product innovations in the US has been to launch an “essentials” brand of orange juice “blends” – combining orange, apple and pear juice – at a lower price.

Similar trends can be seen on British shelves. Orange is being mixed with mango, mandarins and clementine juice. Mango purée is especially cheap right now, driven by a good harvest in India. Mandarin concentrate, meanwhile, is cheaper than its orange equivalent because there is less demand for it.

These developments save money, but also maintain the traditional sweetness of the taste.

Then there is the added impact of the recent spike in trade tensions with the US since President Trump introduced new tariffs.

Oranges, it transpires, have been at the centre of it.

US exports of orange juice to Canada have slumped to a 20-year low after Canada put counter-tariffs on US exports. The former PM Justin Trudeau warned that Canadians might have to “forgo Florida orange juice”.

The Trump administration has also settled on a 10% tariff on orange juice coming from Brazil, which will feed into US supermarket prices.

In 2024, the UK eliminated tariffs on some imports produced from fruit grown outside Britain. But tariffs on certain sweeter, cheaper varieties and blends were not part of this.

And while the tariff cuts might have helped, they were vastly outweighed by the increase in the underlying price.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThen there are new regulations around packaging, further adding to the pressures.

The rules, known as Extended Producer Responsibility, are aimed at improving recycling rates, with a weight-based fee. All juice producers will be impacted, especially those still using glass bottles.

In August a Bank of England report said that high food price inflation is driven partly – and among other things – by these regulations.

In Brazil, the orange harvest has recovered somewhat – this is the greatest hope for a return to normal prices. Yet it coincides with sinking demand: global consumption of orange juice is now down 30% from a peak two decades ago.

Though this may be partly down to the high prices, in certain parts of the world there has also been a shift in perception about the sugar content and health benefits or otherwise of fruit juice.

“When young children are not regularly given juice from an early age, they are less likely to be regular juice drinkers in later years,” suggests Philip Coverdale at GlobalData.

Demand is increasing in countries with growing middle classes, such as China, South Africa, and India. But elsewhere other more exotic fruit juices such as mango, pear and pomegranate are growing in popularity.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesUltimately, however, orange juice is a staple that supermarkets have long been used to selling at low prices. And the price spikes to £2 a carton could, with for example better weather, simply reverse.

“The volatility in the harvest appears to have reduced,” says Giles Hurley, UK CEO of Aldi, “Our buying team are doing everything they can to ensure that that saving is passed on to consumers.”

Others in the supply chain are less convinced, given that much of the frozen concentrate was bought at last year’s high prices. Plus, the stranglehold of the small number of giant producers who control the market remains.

As for the citrus greening, some major commercial producers, including Coca-Cola, which owns Minute Maid and Innocent, have contributed to a project to Save the Orange, using artificial intelligence to find a way to combat it.

It’s a long-term project – and even if fruitful, it may be some time before the effect – if at all – filters through to grocery bills.

But the story of orange prices does also show how an upward price shock gets transmitted around the world far more quickly than a downward one.

Oranges are not the only food that has seen a price spike, of course. The price of beef and veal is up almost 25% in a year. Butter is up almost 19%, and chocolate and coffee 15% and milk over 12%, all according to the Office for National Statistics.

This all suggests that, more generally, there may be something else at play. And that for all the food and drink spikes, the consumer was actually protected from the worst of it for a period – and now it is pay back time.

“It might be the retailers didn’t full pass through the cost increase in the first place and therefore it’s a way of recouping some of the margin they would otherwise have got,” says Steve McCorriston, Professor of Agricultural Economics at the University of Exeter.

EPA – EFE/REX/ Shutterstock

EPA – EFE/REX/ ShutterstockUltimately, though, trying to unpick the precise reason for why our food and drink costs what it does is very difficult – other factors that influence price can go undetected.

“What we don’t know much about is how these supply chains tend to work in practice. It’s difficult to uncover relationships between retailers and manufacturers or farmers and the use of contracts.”

There is also a broader question that goes well beyond orange juice: do consumers in the UK need to simply accept the fact that as a densely populated small country with limited agriculture, a changing climate means the UK will be increasingly exposed to food price shocks?

A 2024 government report on food security noted: “The UK continues to be highly dependent on imports to meet consumer demand for fruit, vegetables and seafood…

“Many of the countries the UK imports these foods from are subject to their own climate-related challenges and sustainability risks.”

And so it could be that this is only the start of a wild ride on what we pay for our food and drink.

Top image credits: Daniel Grizelj/ Tetra Images/ Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.

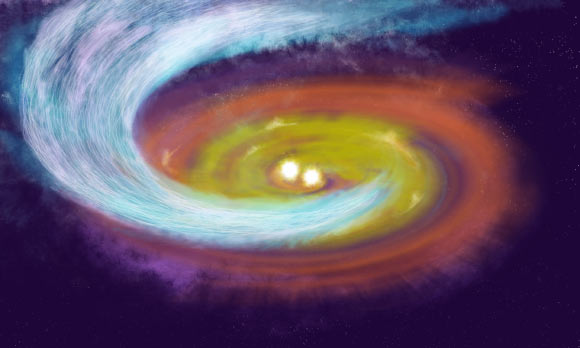

This streamer of gas is channeling matter from the surrounding cloud of a star-forming region in Perseus directly onto a newborn binary star system called SVS 13A.

An artist’s impression of the SVS 13A system. Image credit: NSF / AUI /…

In an age of fierce geopolitical tension, it’s easy to lump all Chinese exports into the same category: state-subsidised oversupply flooding western markets.

However, nothing could be further from the truth when it comes to matcha. As your Big Read shows (“Can Japan satisfy the world’s thirst for matcha?”, October 10), the enormous surge in demand for matcha in the UK and the rest of the world is causing some serious global shortages.

This trend compelled me to turn to China as a source of supply.

As a business owner, I found Chinese matcha to be a great commercial delight. I discovered matcha of comparable grade to Japan’s, for half the price, sometimes even less.

And as a certified tea sommelier, I found Chinese matcha intriguing. Though there was a fair share of pretty rubbish matcha, if one looks there are certainly gems that rival what Japan has to offer. Perhaps not the grand cru of matcha, but premier cru it certainly is.

So perhaps China turning its hand to this rediscovered agricultural export may end up bringing good to the world — or at least to Gen Z and yuppy millennials, who will no longer have to pay £5 for a cup of matcha.

Raphael Chow

Managing Director & Co-founder, Brut Tea, London W1, UK

The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency has issued a warning relating to an actively targeted Microsoft Windows vulnerability that can be found in unpatched versions of Windows 10, Windows 11 and Windows Server.

Tracked as

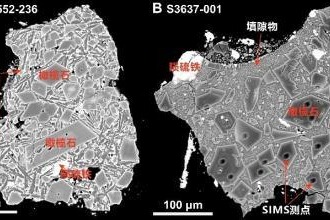

Chinese scientists studying a 2-gram lunar soil sample from the Chang’e 6 mission have identified rare CI chondrite impact residues, providing new insights into mass transfer in the inner solar system and offering new…