- Game Preview: Pacers vs Thunder NBA

- Where To Watch Pacers vs. Thunder? TV Channel, Streaming Options & More For October – 23 NewsBreak: Local News & Alerts

- Oklahoma City faces Indiana after overtime win ABC News – Breaking News, Latest News…

Blog

-

Game Preview: Pacers vs Thunder – NBA

-

MPs ‘pushing hard’ to launch inquiry into Prince Andrew’s Royal Lodge residence | Prince Andrew

MPs on a powerful parliamentary select committee are “pushing hard” to launch an inquiry into Prince Andrew’s residence at Royal Lodge, the Guardian understands.

Keir Starmer has indicated he is open to MPs questioning Andrew in person about…

Continue Reading

-

Evaluating a Mobile App-Based Psychoeducational Program for Dementia C

Introduction

With the ongoing increase in the aging population, dementia has become one of the leading causes of dependence and disability among older adults worldwide.1,2 Current estimates show that over 55 million people are affected by…

Continue Reading

-

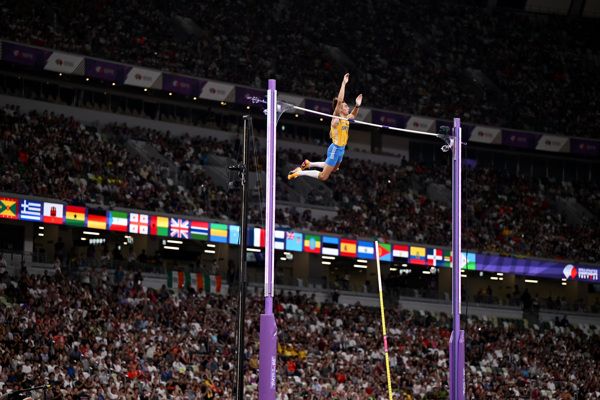

Ratified: world records for Duplantis, Troscianka, Yan and Zhang | PRESS-RELEASES

Men’s pole vault

6.30m Mondo Duplantis (SWE) Tokyo, 15 September 2025Women’s U20 hammer

77.24m Zhang Jiale (CHN) Quzhou, 2 August 2025Women’s U20 javelin

65.89m Yan Ziyi (CHN) Quzhou, 3 August 2025Men’s U20 decathlon

8514 points Hubert…Continue Reading

-

First-generation antihistamines increase delirium risk in older hospitalized patients

An analysis in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society reveals that older inpatients admitted to physicians who prescribe higher amounts of first-generation antihistamines face an elevated risk of delirium while in the…

Continue Reading

-

Novel method measures structure and function of the Achilles tendon in professional ballet dancers

A study in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research uses a noninvasive, nonradioactive imaging-based method to measure the structure and function of the Achilles tendon in professional ballet dancers. The method could potentially be…

Continue Reading

-

High Representative Izumi Nakamitsu Delivers Keynote Remarks at the Singapore International Cyber Week "Shaping the Next Era of Global Cybersecurity" – United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs

- High Representative Izumi Nakamitsu Delivers Keynote Remarks at the Singapore International Cyber Week “Shaping the Next Era of Global Cybersecurity” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs

- Singapore International Cyber Week 2025: Shaping the Future of Cyber Resilience in the Indo-Pacific Australian Cyber Security Magazine

- AISec @ GovWare 2025 to Lead Industry Dialogue and AI Security ANTARA News

- S2W showcases AI security platforms at GovWare 2025 in Singapore – CHOSUNBIZ Chosun Biz

- Criminal IP to Showcase ASM and CTI Innovations at GovWare 2025 in Singapore Yahoo Finance

Continue Reading

-

Just a moment…

Just a moment… This request seems a bit unusual, so we need to confirm that you’re human. Please press and hold the button until it turns completely green. Thank you for your cooperation!

Continue Reading

-

Eagle’s Eye View: Preexisting CVD on the Rise Among Pregnant Women

In this week’s View, Dr. Eagle looks at the social drivers behind the rise in heart disease mortality in California. He then explores the prevalence of preexisting cardiometabolic comorbidities and cardiovascular disease among…

Continue Reading

-

Shared Residual Liability for Frontier AI Firms

As artificial intelligence (AI) systems become more capable, they stand to dramatically improve our lives—facilitating scientific discoveries, medical breakthroughs, and economic productivity. But capability is a double-edged sword. Despite their promise, advanced AI systems also threaten to do great harm, whether by accident or because of malicious human use.

Many of those closest to the technology warn that the risk of an AI-caused catastrophe is nontrivial. In a 2023 survey of over 2,500 AI experts, the median respondent placed the probability that AI causes an extinction-level event at 5 percent, with 10 percent of respondents placing the risk at 25 percent or higher. Dario Amodei, co-founder and CEO of Anthropic—one of the world’s foremost AI companies—believes the risk to be somewhere between 10 percent and 25 percent. Nobel laureate and Turing Award winner Geoffrey Hinton, the “Godfather of AI,” after once venturing a similar estimate, now places the probability at more than 50 percent. Amodei and Hinton are among the many leading scientists and industry players who have publicly urged that “mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority” on par with “pandemics and nuclear war” prevention.

These risks are far-reaching. Malicious human actors could use AI to design and deploy novel biological weapons or attempt massive infrastructural sabotage and disable power grids, financial networks, and other critical systems. Apart from human-initiated misuses, AI systems by themselves pose major risks due to the possibility of loss of control and misalignment—that is, the gap between a system’s behavior and its intended purpose. As these systems become more general purpose and able, their usefulness will drive mounting pressure to integrate them into increasing arenas of human life, including highly sensitive domains like military strategy. If AI systems remain opaque and potentially misaligned, as well as vulnerable to deliberate human misuse, this is a dangerous prospect.

Despite the risks, frontier AI firms continue to underinvest in safety. This underinvestment is driven, in large part, by three major challenges: AI development’s judgment-proof problem, its perverse race dynamic, and AI regulation’s pacing problem. To address these challenges, I propose a shared residual liability regime for frontier AI firms. Modeled after state insurance guaranty associations, the regime would hold frontier AI companies jointly liable for catastrophic damages in excess of individual firms’ ability to pay. This would lead the industry to internalize more risk as a whole and would incentivize firms to monitor each other to reduce their shared financial exposure.

Three Challenges Driving Firms’ Underinvestment in Safety

No single firm is financially capable of covering the full damages of a sufficiently catastrophic event. The cost of the coronavirus pandemic to the U.S., as a reference point, has been estimated at $16 trillion; an AI system might be used to deploy a virus even more contagious and deadly. Hurricane Katrina caused an estimated $125 billion in damages; an AI system could be used to target and compromise infrastructure on an even more devastating scale.

No AI firm by itself is likely to have the financial capacity to fully cover catastrophic damages of this magnitude. This is AI’s judgment-proof problem. (A party is “judgment proof” when it is unable to pay the full amount of damages for which it is liable.) Two principal failures result: underdeterrence and undercompensation. Firms lack financial incentive to continue scaling up the risk they internalize because their liability is effectively capped at their ability to pay. The shortfall between total damages and what firms can actually pay is accordingly externalized, absorbed by the now undercompensated victims of the harm that the firm causes.

This judgment-proof problem is compounded by the perverse race dynamic that characterizes frontier AI development. There are plausibly enormous first-mover advantages to bringing a highly sophisticated, general-purpose AI model to market, including disproportionate market share, preferential access to capital, and potentially even dominant geopolitical leverage. These stakes make frontier AI development an extremely competitive affair in which firms have incentives to underinvest in safety. Unilaterally redirecting compute, capital, and other vital resources away from capabilities development and toward safety management risks ceding ground to faster-moving rivals who don’t do the same. Unable to trust that their precaution will not be exploited by competitors, each firm is incentivized to cut corners and press forward aggressively, even if all would prefer to slow down and prioritize safety.

Recent comments by Elon Musk, the CEO of xAI, illustrate this prisoner’s dilemma in unusually bald terms:

You’ve seen how many humanoid robot startups there are. Part of what I’ve been fighting—and what has slowed me down a little—is that I don’t want to make Terminator real. Until recent years, I’ve been dragging my feet on AI and humanoid robotics. Then I sort of came to the realization that it’s happening whether I do it or not. So you can either be a spectator or a participant. I’d rather be a participant. Now it’s pedal to the metal on humanoid robots and digital superintelligence.

The structure of competition, in other words, can render safety investment a strategic liability.

Traditional command-and-control regulatory approaches struggle, meanwhile, to address these issues because the speed of AI development vastly outpaces that of conventional regulatory response (constrained as the latter is by formal legal and bureaucratic process). Informational and resource asymmetries fuel and compound this mismatch, with leading AI firms generally possessing superior technical expertise and greater resources than lawmakers and regulators, who are on the outside looking in. By the time regulators develop sufficient understanding of a given system or capability and navigate the relevant institutional process to implement an official regulatory response, the technology under review may already have advanced well past what the regulation was originally designed to address. (For example, a rule that subjects models only above a certain fixed parameter threshold to safety audits might quickly become underinclusive as new architectures achieve dangerous capabilities at smaller scales.) A gap persists between frontier AI and the state’s capacity to efficiently oversee it. This is AI regulation’s pacing problem.

Shared Residual Liability for Frontier AI Firms

In a recent paper, I propose a legal intervention to help mitigate these challenges: shared residual liability for frontier AI firms. Under a shared residual liability regime, if a frontier AI firm causes a catastrophe that results in damages exceeding its ability to pay (or some other predetermined threshold), all other firms in the industry would be required to collectively cover the excess damages.

Each firm’s share of this residual liability would be allocated proportionate to its respective riskiness. Riskiness could be approximated with a formula that takes into account inputs like compute, parameter count, and revenue from AI products. This mirrors the approach of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which calculates assessments based on formulas that synthesize various financial and risk metrics. The idea, in part, is to continue to incentivize firms to decrease their own risk profiles; the less risky a firm is, the less it stands to have to pay in the event one of its peers triggers residual liability.

The regime exposes all to a portion of the liability risk created by each. In doing so, it prompts the industry to collectively internalize more of the risk it generates and incentivizes firms to monitor each other.

The Potential Virtues of Shared Residual Liability

Shared residual liability has a number of potential virtues. First, it would help mitigate AI’s judgment-proof problem by increasing the funds available for victims and, therefore, the amount of risk the industry would collectively internalize.

Second, it could help counteract AI’s perverse race dynamic. By tying each firm’s financial fate to that of its peers, shared residual liability incentivizes firms to monitor, discipline, and cooperate with one another in order to reduce what are now shared safety risks.

Thus incentivized, firms might broker inter-firm safety agreements that commit, for instance, to the increased development and sharing of alignment technology to detect and constrain dangerous AI behavior. Currently, firms plausibly face socially suboptimal incentives to unilaterally invest in such technology, despite its potentially massive social value. This is because (a) alignment tools stand to be both non-rival (one actor’s use of a given software tool does not diminish its availability to others) and non-excludable (once released, these tools may be easily copied or reverse-engineered) and so are difficult to profit from, and (b) under the standard tort system, firms are insufficiently exposed to the true downsides of catastrophic failures (the judgment-proof problem). Shared residual liability changes this incentive landscape. Because firms would bear partial financial responsibility for the catastrophic failures of their peers, each firm would have a direct stake in reducing not only its own risk but also that of the industry more generally. Developing and widely sharing alignment tools (which lower every adopter’s risk) would, accordingly, be in every firm’s interest.

Inter-firm safety agreements might also commit to certain negotiated safety practices and third-party audits. Plausibly, collaboration of this sort, undertaken genuinely to promote safety, would withstand antitrust’s rule of reason; but, to remove doubt on this score, the statute implementing the regime could be outfitted with an explicit antitrust exemption.

Firms could also establish mutual self-insurance arrangements to protect themselves from the new financial risks residual liability would expose them to. An instructive analogue here is the mutuals that many of the largest U.S. law firms—despite the competitive nature of Big Law and the commercial availability of professional liability insurance—have formed and participate in. To improve efficiency and curb moral hazard, firms might structure these mutuals in tiers (e.g., basic coverage for firms that meet minimum safety standards, with further layers of coverage tied to additional safety practices) and scale contributions (premiums, as it were) to risk profiles. In seeking to efficiently protect themselves, firms—harnessing the safety-promoting, regulatory power of insurance—would simultaneously benefit the public.

To be sure, firms may well devise other, more efficient means of reducing shared risk. Shared residual liability’s light-touch approach embraces this likelihood. Firms, with their superior knowledge, resources, and ability to act in real time, are plausibly the best positioned to identify and stage effective and cost-efficient safety-management interventions. Shared residual liability gives firms the freedom (and with the stick of financial exposure, provides them with the incentive) to do just this, leveraging their comparative advantages for pro-safety ends. This describes a third virtue of shared residual liability: By shifting some responsibility for safety governance from slow-moving, resource-constrained regulators to the better-positioned firms themselves, it offers a partial solution to the pacing problem.

Finally, a fourth virtue of shared residual liability is its modularity. In principle, it is compatible with many other regulatory instruments; as a basic structural overlay, it is a team player that stands to strengthen the incentives of whichever other regulatory interventions it is paired with. This compatibility makes it particularly attractive in a regulatory landscape that is still evolving.

Shared residual liability might, for instance, be layered atop commercial AI catastrophic risk insurance, should such insurance become available. This coverage would simply raise the threshold at which residual liability would activate. Or it might be layered atop reforms to underlying liability law. Shared residual liability is itself separate from and agnostic as to the doctrine that governs first-order liability determinations; it simply provides a structure for allocating the residuals of that liability once the latter is found and once the firm held originally liable proves judgment proof. (By the same token, as a second-order mechanism, an effective shared residual liability regime requires efficient underlying liability law. If firms are rarely found liable in the first instance, shared residual liability loses its bite, as firms would then have little reason to fear residual liability, and the regime’s intended incentive effects would struggle to get off the ground.)

What About Moral Hazard?

One might worry that shared residual liability, in spreading the costs of catastrophic harms, invites moral hazard. Moral hazard describes the tendency for actors to take greater risks when they do not bear the full consequences of those risks. It theoretically arises whenever actors can externalize part of the costs of their risky conduct. Under a shared residual liability regime, if a firm expects peers to absorb part of the fallout from its own failures, one concern might be that each firm’s incentive to individually take care will weaken.

With the right design specifications, however, moral hazard can be largely contained. Likely the cleanest way of doing so is with an exhaustion threshold: Residual liability would not activate until the firm that causes a catastrophe exhausts its ability to pay. This follows the model of state guaranty funds, which are not triggered until a member insurer goes insolvent. An exhaustion threshold minimizes moral hazard by ensuring that responsible firms bear maximum individual liability before any costs are transferred to peers; solvency functions as a kind of deductible.

An exhaustion threshold, however, may not be optimal in the AI context. Requiring a frontier AI firm to fail before residual liability activates could be counterproductive if that firm is, for example, uniquely well positioned to mitigate future industrywide harm—perhaps because it is on the verge of a major safety breakthrough or some other humanity-benefiting discovery. Its failure not only might disrupt or set back ongoing safety efforts but also could lead to talent and important assets being acquired by even less scrupulous or adversarial actors, including foreign competitors, raising greater safety and national security risks as a net whole. All things considered, it might be better to keep such a firm afloat.

Alternatives to an exhaustion threshold include a fixed monetary trigger (e.g., any judgment above $X), a percentage of the responsible firm’s maximum capacity, or a discretionary determination made by a designated administrative authority. Another approach might be to retain exhaustion as the default, but with exceptions permitted for exceptional cases such as those just gestured at above.

Any moral hazard introduced from lowering the threshold below exhaustion can be addressed via further design decisions. Some moral hazard will be mitigated by a good residual liability allocation formula. When contribution rates are scaled according to a firm’s riskiness (the safer a firm is, the less it stands to owe), firms are incentivized to take care in order to reduce their obligations, countervailing moral hazard temptations notwithstanding. This is akin to how insurance uses scaled, responsive premium pricing to mitigate moral hazard. Additional design tools might include structuring residual payouts from nonresponsible firms as conditional loans that the responsible firm must pay back to the collective fund over time, and restricting access to government grants and regulatory safe harbors for firms that trigger residual liability. Moral hazard is, again, likely most neatly accounted for via an exhaustion threshold, but preexhaustion triggers might also be workable with the right design.

Finally, it is worth noting that moral hazard is not unique to residual liability. It is present under standard tort as well, only it goes by a different name: judgment proofness. Under the status quo, firms may engage in riskier behavior than is socially optimal because they know their liability is effectively capped by their own ability to pay. Any damages above that threshold are externalized onto victims. The cost of moral hazard is borne, in other words, by the public. Under a shared residual liability regime, by contrast, it is shifted to the rest of the AI industry.

Thus shifted, moral hazard—to the extent it persists—can in fact function as a sort of feature, not a bug, of the regime: If firms believe their peers are now emboldened to take greater risks, firms have all the more reason to pressure their peers against doing so. That is, the incentive to peer-monitor grows sharper as concerns about recklessness increase. The threat of moral hazard, thus redirected, can act as a productive force.

***

Shared residual liability is not a panacea. It cannot by itself fully eliminate catastrophic AI risk or resolve all coordination failures. But it does offer a potentially robust framework for internalizing more catastrophic risk (mitigating AI development’s judgment-proof problem), and it would plausibly incentivize firms to coordinate and self-regulate in safety-enhancing directions (counteracting AI development’s perverse race dynamic and helping to get around AI regulation’s pacing problem). By aligning private incentives with public safety, a shared residual liability regime for frontier AI firms could be a valuable component of a broader AI governance architecture.

Continue Reading