Blog

-

Study highlights high prevalence of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity lacking clear markers

Around one in ten people worldwide report gastrointestinal and other symptoms such as fatigue and headache after eating foods containing gluten or wheat despite not having a diagnosis of either coeliac disease or wheat allergy,…

Continue Reading

-

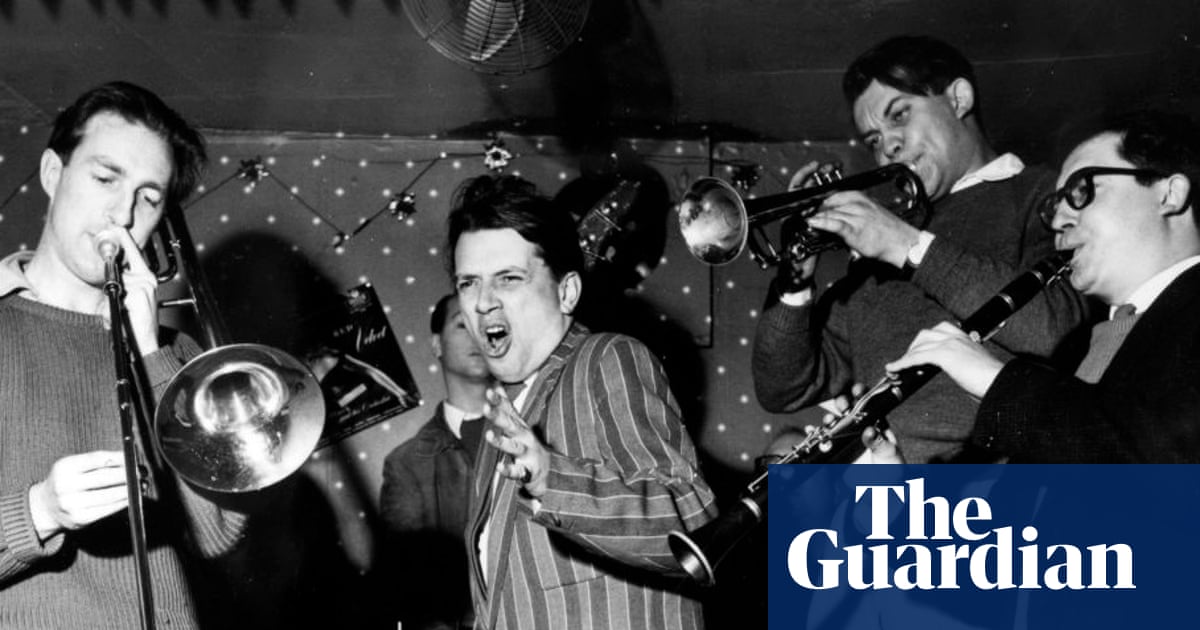

Philip Larkin on George Melly: ‘an adolescent sense of humour’ – archive, 1965 | Jazz

Owning Up, by George Melly (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 30s)

I could never watch (the verb is chosen advisedly) George Melly singing without feeling embarrassed, and the same goes for reading his book. He is so anxious to tell you which birds he had…

Continue Reading

-

Scientist Enhances Century-Old Equation for Air Pollutants

A new method developed at the University of Warwick offers the first simple and predictive way to calculate how irregularly shaped nanoparticles — a dangerous class of airborne pollutant — move through air.

Every day, we breathe in…

Continue Reading

-

$12bn of debt — How First Brands Group collapsed

This is an audio transcript of the Behind the Money podcast episode: ‘$12bn of debt — How First Brands Group collapsed’

Michela Tindera

What does it take to inflict damage on some of the world’s biggest financial institutions? Well, as it turns out, one secret of businessman with a track record of battling creditors in court, and it all starts with a tip.Ortenca Aliaj

I was having breakfast and I got a message from a contact who said they had heard of this interesting company that was potentially having issues.Michela Tindera

That’s the FT’s Ortenca Aliaj. The tip centred around a huge auto parts company, which is a bit out of her field — she’s the FT’s banking editor. But lots of big financial firms had lent this company money, and now it was running into trouble. So, Ortenca mentions it to our colleague Robert Smith. He’s the FT’s corporate finance editor, and he reaches out to some of his contacts. For a while, he doesn’t hear anything back. And then in August, Rob gets a call.Robert Smith

I was sitting there with sort of an incredibly experienced, incredible person telling me that one of the biggest companies in its sector in America was a ticking time bomb.Michela Tindera

The company we’re talking about is called First Brands Group. Not exactly a household name but it’s a business with a collection of factories from Pennsylvania to California — ones that make spark plugs, brake components and windshield wipers. It’s an auto parts supplier basically, and it’s from the Rust Belt of the United States.So not typically the kind of company that would cause the upper echelons of Wall Street to lose sleep over. Yet that’s exactly what happened last month when First Brands collapsed.

And as Rob, Ortenca and our colleagues worked together on the First Brands story, they unveiled something possibly even more troubling: a form of Wall Street lending that’s exposed financial markets to broader risk, risk that’s even got central bank leaders worried.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

I’m Michela Tindera from the Financial Times. Today on Behind the Money, First Brands’ bankruptcy has raised questions about one of Wall Street’s favoured forms of financial innovation: the $2tn private credit market. This form of lending is often opaque, and there’s concern that after years of loosening lending standards, First Brands’ demise could be an omen.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

There are many questions in this story, but let’s start with one of the biggest. It concerns the founder of First Brands, a mysterious businessman called Patrick James. How did this obscure entrepreneur, based in the Midwest state of Ohio, enlist some of the biggest names in finance to lend his firm, not just millions, but billions?

Who is he? Well, the story begins sometime after the 2008 financial crisis when Patrick James goes on a debt-fuelled acquisition spree. Here’s Rob.

Robert Smith

So Patrick James, he borrowed a lot of money to buy existing companies and sort of piece them together. So one of the early deals he did was in 2014, and he bought a windscreen wiper maker or a windshield wiper maker, as you say in the US, called Trico. And then sort of every year he’d announced any deals. So you know, buying a carburettor maker, buying a spark plug manufacturer. And each time he did it, he borrowed more and more money and the group became bigger and bigger. And then it was in 2020, I believe, he rebranded the company First Brands Group.So, you know, he’s kind of saying: We’ve got all the brands. We are the First Brands Group. If you want your Trico windscreen wipers, we’re there. You know, if you want your Michelin-branded tires, we are the guys. And like a lot of schemes that go awry or like a lot of companies that blow up, he had a good pitch.

Michela Tindera

One of the first major Wall Street firms to latch on to the First Brands’ pitch is the investment bank Jefferies.Robert Smith

Jefferies got involved with First Brands very early, so in 2014, before it was even called First Brands, and they basically were there to shepherd it into the market to help it borrow this money from these private investment firms.And Jefferies, it’s tried to model itself from what it would describe as a pure play investment bank. So sort of like the investment banks of your . . . where kind of swaggering bankers went out and won business. And they lived and died by the strength of the service they could offer their clients.

Michela Tindera

Jefferies isn’t the only firm to give them money. In fact, Jefferies has since pointed out that they were aware of nine other banks being involved in acquisitions or loan arrangements for First Brands. And that’s because in part, as Patrick James builds up First Brands in the wake of the financial crisis, a new area of finance is on the rise: private credit. It’s a form of lending that Ortenca as the FT’s banking editor is watching closely.Ortenca Aliaj

After the financial crisis, regulators sought to restrain banks because they’ve been doing all of these risky trades that almost led to the collapse of the global economy. And one of the repercussions of this was that they would effectively make it much more onerous for banks to lend to highly levered borrowers or companies that have a lot of debt on their balance sheet, which tend to be mid-sized businesses.And what happened was that there were, these very, very smart people on Wall Street who thought, well, if banks can no longer enter these businesses, we could set up firms that can. And that was sort of the genesis of the private credit industry. It wasn’t that it hadn’t existed before, but there was this kind of new borrower or new market that they could easily cater to.

And so it was kind of fortunate that as Patrick James was trying to build this business of his, there was a group of lenders ready to lend to him that perhaps are more lenient in terms of scrutiny than maybe a bank would’ve been.

Michela Tindera

So First Brands grows alongside this boom in private credit. Lots of big financial institutions from Zurich to Tokyo become tied up in this business. Along the way, Patrick James amasses the trappings of a billionaire.Robert Smith

I think what’s interesting is before the collapse of First Brands, this was sort of a big immigrant success story. Patrick James, he’s Malaysian. He’s from like a family of Indian descent and then he later moved to America for college with seemingly not a lot of wealth. But he sort of stuck around in Ohio and he very quickly became involved in a lot of different industrial businesses.And then at the sort of peak of First Brands, he amassed this very lavish sort of lifestyle. He had oceanfront properties on both coasts. So he had a big oceanfront property in Malibu, had a big oceanfront property in the Hamptons. He had almost, like, I’d call it almost like a compound in Ohio. So it’s sort of like five houses and a tennis court. So you had a lot of trophy homes all around America.

Michela Tindera

And that brings us up to this past summer and the tips we heard about earlier, the ones Ortenca and Rob received from their contacts. Now, as they’re digging in, they learn something. In early August, First Brands had been working to refinance its debt once again with the investment bank Jefferies. But this time something went wrong.Robert Smith

So this company raised debts constantly. It needed to keep accessing debt markets to survive. So they tried to do a $6bn debt refinancing. So that’s essentially when you raise new debt to pay off the old debt. It’s quite a large deal. And it ran aground because lenders took a look at this and they had concerns about the financial statements.But what we discovered through our sources was that First Brands was also raising sort of a lot of less visible financing, stuff that behaved a lot like debt but perhaps wasn’t disclosed as debt on the balance sheet. And we sort of had people saying that they believed there could be billions of dollars, more of this stuff than perhaps everyone realised.

Michela Tindera

OK. So to sum it up here, this company, you’ve just received a tip about. You have people telling you that it could have billions more dollars of debt than anyone knows about. I mean, what was going through your mind as you uncovered all this?Robert Smith

I think the thing that really shocked us was this was a company neither of us had heard of.Ortenca Aliaj

Yes.Robert Smith

And we write a lot about debt markets. And as soon as we did our research, we found out this thing was a debt monster, and we kind of discovered that some of the biggest names in international finance had exposures that weren’t well understood. So for us it was kind of an “Oh, my God” sort of moment. There’s this sort of debt bomb lurking out there that no one really seems to know anything about.Michela Tindera

So Rob and Ortenca have found a debt bomb hidden away and supposedly it could go off at any moment. So they and two of our colleagues write about this in the FT, and the reaction to their reporting is fairly muted.Robert Smith

No one really freaked out. And then about, I think it was just over a week later, we published a second story.Michela Tindera

This time, people sit up and take note.Robert Smith

And in that second story, we revealed that a very big Wall Street firm called Apollo Global Management had taken a short position against First Brands’ debt. Now, that meant that it would make money if the company entered financial difficulties. So, debt can trade like a stock can trade, and when people have concerns around a company, that debt trade is down and the company’s debt immediately crashed. And from there, in a matter of weeks, it went from this kind of freak out in debt markets to the company filing for bankruptcy.Michela Tindera

September 28th this year. That’s when First Brands files for bankruptcy.Robert Smith

When we first wrote about the company, it had told investors it had $800mn of cash on its balance sheet. When it filed for bankruptcy at the end of September, it had $12mn in the bank. So something went completely wrong with this company. There was almost like a bank run on the company’s cash and it was just a complete fire sale. So some of the biggest institutions on Wall Street were just dumping their debt. I don’t think it’s too hyperbolic to say it was complete carnage.Michela Tindera

A couple weeks later, the US Department of Justice announces its launching an inquiry into the collapse of the firm. Days after that, First Brands CEO Patrick James steps down and all the while Rob, Ortenca and some of our colleagues are parsing through these bankruptcy documents. That’s where they learned that what their sources had told them that First Brands had billions more of this off-balance sheet debt, that it was even more true than they had imagined.Robert Smith

So First Brands had about $6bn of loans. So those are like the normal sort of loans that in the past would’ve been made by banks. A lot of them were made by investment firms. But on top of that, it had a lot of what is called off-balance sheet debt, and what that broadly means is that in the company’s accounts, this wasn’t disclosed as debt.Michela Tindera

Well, how does that work? How does a company accumulate debt but then the debt doesn’t appear on its balance sheet?Robert Smith

So, you know, First Brands was borrowing money; it was borrowing money from lenders. But on top of that, it was raising this other form of financing that was tied to its invoices and tied to the little bits and bobs of metal sitting around in its warehouse. And this is all quite normal stuff in finance.The crucial point there is that while you owe money to a bank, it’s not classed as debt on your balance sheet. It’s sort of mingled in with all the other invoices you pay suppliers. So it’s a bit of a loophole where if companies abuse it, they can rack up hidden debts quite quickly.

So it came out in the bankruptcy that there was a total of nearly $5.5bn of this off balance sheet financing in different forms. So you had people who thought: OK, there’s $6bn of debt out here. And then they wake up one morning and read the disclosure in the bankruptcy and they realise: Oh my God, there’s nearly $12bn of debt here.

Ortenca Aliaj

It’s almost double, basically. And it’s really crucial to make the point that — and maybe it’s a simple point, but should still be made — having a high debt load, not a crime, there’s a lot of highly leveraged companies. That’s fine. Having debt that your creditors don’t know about, can become quite a problem for you and your creditors.[MUSIC PLAYING]

Michela Tindera

Big financial names like UBS’s Chicago-based hedge fund unit O’Connor, US hedge fund giant Millennium and Japan’s Mitsui & Co and Norinchukin Bank, all provided this form of financing: off balance sheet financing to First Brands. And the story of how other lenders missed all that debt, that’s a story that tells us a lot about how private credit markets work and how opaque they can be.[MUSIC PLAYING]

In the course of their reporting, Rob and Ortenca found a number of red flags at First Brands that Wall Street lenders either missed or chose not to be concerned about. One of their first stops was to look into the background of First Brands CEO, that mysterious businessman Patrick James.

Ortenca Aliaj

So usually when we’re dealing with a person that we are not familiar within the business world, what I will try to do is go through various government filings to see if they’ve been mentioned in anything.And I’m looking on the Securities and Exchange Commission website, which houses corporate filings, and I find a reference to Patrick James and the company First Brands Group. It’s in relation to an acquisition that they made a couple of years back. I’m sort of like: Well, great. We’re gonna find some more details about him.

But the profile of James is basically one line, and I think all it says is that he has extensive experience in the automotive after-market industry. So we find ourselves in this position where we really know very little about him. We can find biographies from the high school that he went to, but we don’t know what this person has been doing in the corporate world for the past 30 years.

Michela Tindera

Even First Brands’ lenders were in the dark about who Patrick James is.Robert Smith

When we talk to the lenders who are the people who should know the most about this company, they didn’t know anything or very little about Patrick James either. And this guy was the chief executive, but he was also the 100 per cent owner of the company.Ortenca Aliaj

And again, this is a man who, despite all of that, has accrued $12bn of debt. And we can’t, you know, we can’t find any reference to him really . . . any meaningful reference to him on the internet.Robert Smith

So it was kind of a strange moment and almost the red flag in and of itself.Michela Tindera

One of the things Rob and Ortenca were able to find out quite quickly though was James’s colourful legal past, which included a string of failed companies behind him.Ortenca Aliaj

And very quickly we uncovered that there had been prior accusations of fraud against James, and the accusations were eerily similar to what we were hearing on First Brands Group.Michela Tindera

More than a decade ago, two lenders in separate cases sued Patrick James.Robert Smith

So in one of those lawsuits, the bank that filed the claim against Patrick James, it accused him and his businesses of making “misrepresentations and omissions” relating to their invoices and inventory. So that was really interesting because it seemed to be relating to the same sort of financing that was at the heart of First Brands collapse.And then there was another lawsuit where James was accused of creating a “web of companies” to transfer out funds “in an attempt to defraud” creditors. So he was basically accused of creating this very complicated, shifting group of companies in which the allegation was that money was siphoned out of them.

Michela Tindera

It’s worth noting that Patrick James, through a spokesman has said these allegations are, quote, categorically false. The cases were robustly defended and never tried after settlements were reached. These were civil claims where serious allegations are often made, which turn out to have little substance. Certainly nothing criminal was ever brought against Patrick James.In fact, James’s spokesman also told the FT about our reporting on his back-story that James hasn’t been accused of any wrongdoing and is confident that the board’s independent investigation will vindicate him. But beyond Patrick James’ legal history, there were other issues that Rob and Ortenca learned about related to the First Brands’ business and its debt.

Robert Smith

So a really easy one was that First Brands Group had significantly higher margins than its peers. And the auto sector generally is quite a tight margin business, right? These guys ring out every cost they can, and they found that they just couldn’t really get a good explanation of that. And that was something that made some investors like not lend to the company and other lenders decide to not lend in the future.Michela Tindera

Plus, there was the issue of collateral for First Brands loans. As Rob mentioned, the company was using its inventory, the bits and bobs of metal in its warehouses as collateral, but many lenders didn’t bother to check whether that collateral even existed.Robert Smith

Now the classic thing you do when you lend against inventory is you go to the warehouse. You look at the stock list, you go around, you see if the things are there, you, know, you kick a few boxes. And we discovered that First Brands, so Patrick James’ brother Ed James was sort of the point man, shall we say, for the stuff.And we talked to some lenders who, you know, were approached about doing inventory finance. And they said: OK, great. Well we’ll come down to your warehouse and we’ll check it against the stock list. And then they were sort of cut off there. You know, supposedly Ed James said: No, no, no, no, no. We don’t let lenders into the warehouse. You can’t do that.

So you can imagine for a lot of people that was just a non-starter. They were like: We’re not gonna lend against a bunch of stock in a warehouse if we haven’t even seen it.

Michela Tindera

Now we should be clear that the business First Brands has not been charged formally with fraud. Still, it all begs the question: where was the due diligence? How did First Brands manage to keep securing more and more from lenders with no one lifting up the hood on its business?Robert Smith

What I think this tells you about the structure of modern finance is that it doesn’t pay to do deep due diligence on the companies you’re lending to. People in managed investment funds, the way they make money is by earning fees, and the way they earn fees is by lending. So a lot of these people were relying on the disclosures that were given to them by the company and by the investment bank, which was often Jefferies, and they perhaps didn’t have the time to really dig into the accounts.Michela Tindera

But Ortenca says there’s a big picture to consider too.Ortenca Aliaj

We’ve had 10 or 15 years of what we like to call the easy money era, where there’s been this abundance of cash going into the private capital industry, so they’ve had to find more and more opportunities to use it, and that can lead to slightly looser lending standards. Mark Rowan, the chief executive of Apollo, who as we’ve said, made a bet against First Brands before the company went under, has called these “late-cycle accidents”.Michela Tindera

Add to that a sense that someone else, another lender, was assumed to be doing their homework on First Brands.Ortenca Aliaj

Usually what these companies do when something does happen like this is they’ll pass the buck. They’ll say: Oh, well the company had an auditor. It’s the auditor’s fault. And then some will say: Well, you know, we bought the debt from a bank. The bank should have done the due diligence. Then, you know, an investor in private credit say: Well, well, private credit bought the loan. So why would we do the due diligence?So it’s sort of like everyone relies on the fact that the person before them performed good due diligence on the company and they are almost absolved of responsibility of actually having done it themselves.

Michela Tindera

So Rob, how likely is it that we see more of these situations pop up?Robert Smith

I was lucky enough a couple of weeks ago to talk to Jim Chanos, who’s one of the most famous short sellers on Wall Street. You know, he’s known as the man who spotted the Enron fraud before it unravelled. Right? And he had a really interesting thing to say. He was basically saying what he calls the fraud cycle follows the financial cycle. So what he meant by that is when money rushes into an asset class, that is a fertile ground for fraud.So the way he explained it is like the longer a sort of boom goes on, the more investors’ healthy scepticism starts to erode because everyone else is making massive returns and you know, they might not really be doing the work.

So you start to think: Oh, well, you know. Ah, I dunno about this, but God, if everyone else is doing it, you know, I’ve got my end investors turning around to me and saying, why aren’t you investing in these companies? Why aren’t you doing these loans?

So it just sort of wears you down. And if there’s like years and years without incident on Wall Street, you think, OK, well. Yeah, it’s probably safe. I don’t fully understand it, but I’ll just go with it.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Michela Tindera

So a few weeks ago, our listeners might remember that we covered the collapse of the Texas-based subprime auto lender called Tricolor Holdings. Looking at these two stories, there are a lot of similarities. How should we think about that?Robert Smith

Yeah. I think what’s interesting here is when you have an incident like this, it obviously frightens people. So what you get is you get people taking a closer look at the sort of lending they’ve done.You know, Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan, on an earnings call recently, he said: There’s rarely one cockroach. So you know, the analogy there is you see a cockroach in your kitchen, there’s probably a few more of the guys, right?

So I think that’s what everyone’s trying to work out at the moment. People are looking over the asset-backed lending they’ve done, they’re looking over the corporate loans they’ve done and they’re trying to see: Is there another First Brands?

Michela Tindera

Do we know anything about how regulators are thinking about the news of these recent collapses?Robert Smith

I think it’s really caught the attention of regulators because in the financial crisis a lot of the issues were with banks, and although it was, you know, nearly catastrophic, regulators do have a lot of insight over banks.Partly because of the rules that they introduced to stop this happening again, a lot of that lending is migrated away from banks and into investment funds, and regulators just have much less visibility in what’s going on there. There’s also a phenomenon where often the banks are lending to the private credit funds, so there can still be a knock-on into the banking system.

And this is the area where sort of central bank governors, policymakers, those sort of people are getting worried. So Andrew Bailey, who’s the governor of the Bank of England, he said earlier this month that alarm bells were sort of ringing over what’s going on in private credit. And he mentioned First Brands and Tricolor by name.

You also had the head of the IMF, the International Monetary Fund, she said there’d been a very significant shift in financing away from the banks to what they call non-bank lenders. And again, she mentioned Tricolor and First Brands as sort of worrying signs of what might be going on.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Michela Tindera

Behind the Money is hosted by me, Michela Tindera. This episode was produced by me and Saffeya Ahmed. Our executive producer is Manuel Saragosa. Fact-checking by Simon Greaves. Sound design and mixing by Sam Giovinco. Original music is by Hannis Brown Topher Forhecz is the FT’s acting co-head of audio. Thanks for listening. See you next week.Continue Reading

-

Amazon’s Jeff Bezos spotted wearing rare $2.4 million Richard Mille timepiece; Inside the billionaire’s luxe watch collection – Lifestyle News

Jeff Bezos net worth: Amazon founder, Jeff Bezos, was once the richest man in the world, with a net worth of $241 billion, according to Forbes. He is the fourth-richest billionaire in the world. Recently in the spotlight for his Venetian wedding…

Continue Reading

-

China buys three U.S. soybean cargoes ahead of Trump-Xi meeting, Reuters reports

China’s state-owned COFCO bought three U.S. soybean cargoes this week, two trade sources said.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

China’s state-owned COFCO bought three U.S. soybean cargoes this week, two trade sources said, the country’s first purchases from this year’s U.S. harvest ahead of this week’s summit of leaders Donald Trump and Xi Jinping.

COFCO purchased about 180,000 metric tons of soybeans for December and January shipment through Pacific Northwest port terminals, the sources said.

COFCO did not immediately respond to a Reuters request for comment.

Benchmark Chicago soybean futures prices jumped this week to their highest in 15 months, rebounding from recent five-year lows on hopes for a U.S.-China trade deal.

China, the world’s biggest soy importer, shunned soybeans from the autumn U.S. harvest, switching its demand to South American suppliers amid trade conflict with Washington.

The unusual delay has already cost U.S. farmers billions of dollars in lost sales, after they largely supported Trump in his campaigns for president.

Continue Reading

-

Bessent calls on Japan to let central bank fight inflation – Financial Times

- Bessent calls on Japan to let central bank fight inflation Financial Times

- Bessent says Japan government gives Bank of Japan policy space, avoid excess FX volatility investingLive

- AUD/JPY gathers strength above 100.00 on hot Australian CPI inflation data FXStreet

- Japanese yen strengthens after officials ease policy concerns CNBC

- Bessent from the US Treasury believes Japan’s government supports BoJ, stabilising inflation and currency fluctuations VT Markets

Continue Reading

-

A dynamite film, but a house of cards on nuclear reality

Three years ago, when I was serving at the US National Security Council, we were faced with a nuclear crisis. As Bob Woodward described it in his book War, the Intelligence Community assessed that if Russian forces were facing a collapse in…

Continue Reading