TV

If you only watch one, make it …

Riot Women

BBC iPlayer

Summed up in a sentence Sally Wainwright returns, with an energetic drama about a group midlife women who form a punk band.

What our reviewer said “It is, of…

BBC iPlayer

Summed up in a sentence Sally Wainwright returns, with an energetic drama about a group midlife women who form a punk band.

What our reviewer said “It is, of…

The age-old question from the back of the car feels just as pertinent as a new era of autonomy threatens to dawn: are we nearly there yet? For Britons, long-promised fully driverless cars, the answer is as ever – yes, nearly. But not quite.

A landmark moment on the journey to autonomous driving is, again, just around the corner. This week, Waymo, which successfully runs robotaxis in San Francisco and four other US cities, announced it was bringing its cars to London.

The detail remains scant, but the promise eye-catching: the pioneering Silicon Valley company said it was bringing its fully autonomous service “across the pond, where we intend to offer rides – with no human behind the wheel – in 2026 … We can’t wait to serve Londoners and the city’s millions of visitors next year.”

Those millions may want an Oyster card for the London Underground, just in case. The UK government, intent on luring big tech, in the summer set out plans to speed up the introduction of driverless cars, meaning robotaxis could start operating in regulated public trials as early as spring 2026. But the rules are yet to be fully established, and testing may include a safety driver for some time.

British firm Wayve, in partnership with Uber, has issued the slightly more sober “plan to develop and launch public-road trials of level 4 fully autonomous vehicles in London.”

While Americans sit back and enjoy the autonomous ride, Britain’s winding road to driverless cars has been marked by pledges that vanished like pedestrians in the rain. In 2018, Addison Lee – once the future – was promising, along with Oxford University scientists, to be launching robotaxis by 2021.

A year earlier, Nissan almost managed to get one of its Leaf cars to drive itself around Beckton in east London without crashing. Chris Grayling, then transport secretary, said self-driving cars would be on the market in four years, as little pods tootled autonomously around the O2 in Greenwich. A British invention, a union jack-liveried Sinclair C5-Tardis love child, appeared in a Milton Keynes car park in 2015; then business secretary Vince Cable said 100 of them would soon be carrying passengers round town for £2 a pop.

Yet abroad, particularly in America and parts of China, autonomous taxi services are now very much a reality – meaning Waymo’s arrival appears more significant than previous hype or hope.

In San Francisco, Waymo’s home town, its driverless cars have become a routine part of urban life, humming along the hilly grid of streets at a cautious yet purposeful pace.

Since their full launch in June 2024 they have taken their place alongside the city’s electric scooters and municipal buses. Taking a Waymo has become as much of a must-do tourist experience as riding one of the city’s historic trolley cars.

The Democrat mayor, Daniel Lurie, has encouraged expansion to revitalise downtown areas, where the streets remain inhabited by many homeless people – leading to the jarring juxtaposition of cutting-edge AI-controlled robocars rolling past those in extreme poverty.

With fast spinning cameras on each wing and one on the roof like a police siren, the converted white Jaguar iPace vehicles look like surveillance infrastructure. They are hailed like Uber or Lyft rides from smartphone apps – but the absence of a human in the driver’s seat, and the steering wheel turning under the control of an invisible algorithm, are reminders of the economic ructions they are causing.

In 2010 Uber launched in San Francisco, upending the way taxi drivers were employed and ushering in precarious gig work. Now those Uber drivers are facing a second wave of technological disruption.

According to data cited by the Economist, the number of people employed in San Francisco in taxi firms grew by 7% in 2024; and pay rose by 14%. It quoted David Risher, the chief executive of Lyft, predicted that self-driving taxis “will actually expand the market”.

But not all necessarily feel that way on the frontline. In the Mission district of San Francisco, asked about Waymo, one Uber driver from Venezuela replied: “I think I’ve got about a year left in this job.”

For a customer, to ride in a Waymo is to feel abandoned to the control and power of artificial intelligence. Once hailed via the app, the car pulls up gently, showing the customer’s initials on a digital display on the roof hub. A tap on the app unlocks the car doors; a welcoming voice reminds riders to buckle up. A screen offers a wide menu of music to cruise along to behind the tinted rear windows, in a truly private space.

Tap the “start ride” button on the touch screen and the car pulls confidently away into the streaming traffic. The steering wheel, with its “please keep your hands off” sign, spins like a funfair ghost train ride.

It doesn’t take long to feel comfortable, as it swerves hazards, errs on the side of caution. Screens with scrolling street maps track progress and update the arrival time while the “pull over now” button is a welcome reminder that it is possible to override the original destination instruction, although it will only pull over when safe.

Waymos have prompted a multitude of social reactions. When three stalled in an intersection of a busy nightlife zone in the Marina area last month – apparently confused, lights flashing – revellers whooped with delight and one man executed multiple backflips from the roof of one of them.

In July, a prankster organised people to a dead end street to all order Waymos at the same time simply to create the spectacle of a cluster of 50 of the robocars. In early 2024, when Waymos were in use in more limited numbers, one was smashed, daubed with graffiti and torched during lunar new year celebrations in the Chinatown area.

A similar reception could await driverless taxis here – even if not personally at the hands of black cab drivers. General secretary of the Licensed Taxi Drivers Association, Steve McNamara, said: “You see kids hacking Lime bikes – how long before it becomes the latest TikTok craze to surf on the roof of a Waymo?”

McNamara claims to be relaxed: “It’s a solution to a problem we don’t have. These vehicles, that work so well allegedly in San Francisco and LA – London is like nowhere else. I want someone to explain to me how this driverless car is going to go somewhere like Charing Cross Road at 11pmt, where everybody’s just walking across the road. As soon as you see the Lidar dome [sensor] on the top of the Waymo car, you’re just going to step out, or pull out in a car, because you know it’s going to stop.”

Christian Wolmar, the author of Driverless Cars: On a Road to Nowhere, concurs: “We do not have jaywalking rules here – and if Google expects that we’re going to introduce jaywalking rules for the sake of their cars …”

Despite the US experience, he remains resolutely sceptical that fully driverless taxis will appear here next year: “Without a human operator, absolutely zero chance.”

Waymo, which announced its London plans partly to pre-empt sightings of test cars on the streets beginning the long mapping process, is feeling confident after some 100m miles of autonomous journeys in San Francisco – a city far from flat and orderly – and trials in a dozen more.

Operators have long maintained that regulation, rather than technology, is the challenge. Even fast-tracking has its limits: the results of a consultation that closed last month should – although not confirmed – allow the pilots to go ahead.

That may have been the trigger for Waymo, but it still needs to jump through a number of Department for Transport and Transport for London hoops to get the test scheme motoring – and the wider legislation will not be in place for at least two more years. Insurers, in particular, say many questions remain about liability.

Similar pre-legislative pilot schemes have left other novel transport forms in limbo: e-scooter “trials” are now set to last eight years. Tony Travers, the LSE professor of government, believes driverless cars have a better chance: “They have to obey the rules. They could lead to congestion – but not the near-anarchy that the e-scooters have caused.”

But even if driverless taxis appear, the wider question, Wolmar says, is, “so what?”

According to the Waymo co-CEO Tekedra Mawakana, the answer is in the cars “reliability, safety and magic”, with a big emphasis on safety. Waymo cars to date have been involved in a fraction of the incidents of human-driven cars over the same distance.

It also hopes to bring a different form of autonomy to those who may have lacked it: the Royal National Institute of Blind People welcomed Waymo’s news as a dawn of “technology that can safely enable spontaneous autonomous travel”.

Waymo said its entry into the UK market would mean investing in depots, charging infrastructure, and cleaning and support teams, and “human specialists” in the driving seat for now.

Heidi Alexander, the transport secretary, has said the impending autonomous vehicle revolution could create 38,000 UK jobs.

But more evidently at risk are professional drivers: 300,000 or so who are licensed for private hire – and, further down the line, another million in HGVs and delivery. Many of Britain’s 82,000 bus drivers have recently won significant pay rises; and the 27,000 train drivers are famously well heeled.

Little wonder that polling suggests public opinion in the UK is barely positive about driverless cars, in a backdrop of general anxiety over the potential for artificial intelligence to eliminate human jobs, if not yet humans.

The licensing and legislation awaits. McNamara is upbeat: “Who’s going to sign it off? If I was looking for a successful career in politics I wouldn’t be putting my name on that piece of paper.”

SINGAPORE, Oct. 18, 2025 /PRNewswire/ — SCG Cell Therapy Pte Ltd (SCG), a clinical-stage biotechnology company developing next-generation immunotherapies for infectious diseases…

Max Verstappen took his 10th Sprint pole in 22 Sprint weekends with a superb final lap at Austin’s Circuit of The Americas to edge out the McLaren of Lando Norris by the smallest of margins. But have the Dutchman and his Red Bull team got what it…

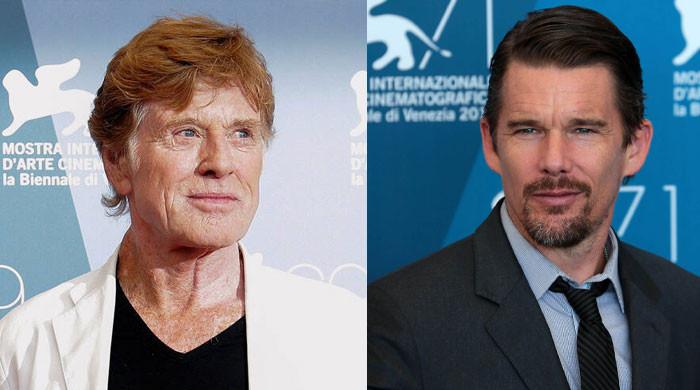

Ethan Hawke fondly remembers a “really funny” piece of style advice from the late Robert Redford.

Hawke, 54, shared the piece of advice while speaking with AARP…

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The problem with a pensions crisis is that you might not know you’re in one until it’s too late to do anything meaningful about it.

Take Gen Z. The average 18 to 28-year-old hopes to retire at 60, according to new research from Standard Life. It’s an ambitious aspiration that’s well ahead of their state pension age of at least 68 (who knows what it will be by the time they come to retire — if it exists at all).

But there’s a bigger problem. Wealth manager Rathbones put out an alarming study recently saying that when they come to retire, Gen Z will need a pension of at least £3.1mn to afford a comfortable retirement. It arrived at that figure by taking the £1.4mn pot it thinks you need today and applying inflation to it for 65 years, spanning working life and 25 years of retirement, at 2 per cent a year.

Whether that figure works out to be accurate — I happen to be sceptical myself — or it’s £2mn, £1.8mn or less, younger workers can’t take it for granted that they’ll be able to afford a long, comfortable retirement.

Many “Zoomers” have portfolio careers, sometimes relying on gig work or holding down multiple part-time jobs — not ideal conditions to start building a nest egg. Add in high student debt and unaffordable housing, and it’s no surprise that Standard Life found this week that only 13 per cent are prioritising pension saving.

The big mistake is believing that minimum contributions via auto-enrolment to a workplace scheme will deliver. Standard Life found that 59 per cent of Gen Z think this.

If a 25-year-old earns £35,000 a year, the minimum level auto-enrolment saving level is £2,300 per year. Government figures show the average additional savings at this salary level amount to only an extra £560 per year — that’s never going to get you anywhere near £3.1mn. Assuming wage growth in line with inflation and a 5 per cent return on your pot every year, wealth manager Rathbones calculates that a 25-year-old needs to put away £1,600 a month.

That may seem like an unrealistic figure, but deferring until a time in the future when your pay is much higher is also not the most sensible tactic. If you want to turbocharge your pension, the time to act is now.

Take it from me, those early days are the most powerful force you can harness in your financial life due to the power of compounding. My pension from six years in my 20s — when I was a low earner — is now, in my 50s, worth easily more than the one in my 40s when I earned significantly more.

The first thing to do, if you’ve had frequent job changes, is consolidate any small deferred pension pots you may have accumulated from working in different jobs. I consolidated the ones from my 30s and 40s (alongside some little stray pots) but left that one from my 20s on its own as it had low fees. Moving them into a self-invested personal pension (Sipp) can stop you losing track and might even lower the cost. Independent website Money to the Masses says the cheapest Sipp is Vanguard’s up to £100,000 and then Interactive Investor for larger portfolios.

Then check what you’re invested in. If your workplace pension is in the default fund, equity exposure is likely to be low — perhaps as low as 50 per cent. Analysis of default funds by PensionBee found that average returns are below the 5 per cent level that many would consider to be “good”.

If you’ve got three decades until retirement, your capacity for risk is as high as it’s ever going to be, so you might want to consider being all in equities.

It’s also the time to put in as much extra money as you can. In your 20s or 30s, maximising your pension funding up to £60,000 a year or your earned income — whichever is the lower — only for a few years can have a massive impact. Wealth manager Tideway Wealth calculates that £180,000 added to your fund in your early 30s, which might cost only £100,000 after tax relief, could add £580,000 in today’s money to your fund by the time you hit your early 60s.

Another tactic — admittedly only open to the luckiest — is to ask for assistance. Wealthy parents and grandparents are increasingly providing a helping hand, financial advisers report, since they will have to pay inheritance tax on any unspent pension passed on from April 2027.

Gifts from spare income will immediately reduce an estate for IHT purposes. Plus, donors will see some money recouped via tax relief on pension contributions — satisfying for those peeved by paying extra income tax in an attempt to run down their pensions faster. Since the child or grandchild won’t be able to access the money until they are at least 57, it at least reduces the fear the money will be squandered on fast living.

“It’s a win-win from a tax perspective on both sides of the generational equation,” says Charlotte Ransom, chief executive of Netwealth, a wealth manager. “It can generate very meaningful, long-term value with efficient compounded returns and avoids the risk of the money being spent unwisely during younger years.”

James Baxter, founder of Tideway Wealth, says: “We have several early 30-year-olds who already have around £100,000 in both an Isa and a Sipp funded entirely by their parents. These were accumulated in their early careers when they were not earning that much and it would have been impossible to save much on their own.”

So, with just under 10 weeks to go until Christmas, Gen Z know what to say when they get asked what present they’d like under the tree: a slug of money in their pension.

Moira O’Neill is a freelance money and investment writer. Email: moira.o’neill@ft.com, X: @MoiraONeill, Instagram @MoiraOnMoney

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

People who buy expensive cars do so because they are keen on roaring engines, buttery-soft interiors and iconic logos. What doesn’t play into their purchasing decisions, apparently, is how environmentally friendly the vehicles are.

Responding to customer preferences, Ferrari said last week that it only expects 20 per cent of its models to be fully electric by 2030, down from 40 per cent previously. Porsche last month delayed a new range of high-end EVs, with chief executive Oliver Blume — who may be on the off ramp at the sports-car maker — citing a drop in demand for exclusive battery-electric cars. Mercedes has also seen weak EV sales, although third-quarter numbers improved.

That’s somewhat of a contrast to the mood in the broader EV market, which — amid ups and downs — sold a record 2.1mn vehicles in September. There are lots of reasons why luxury EVs are failing to get traction. One is that China is the biggest market in the world, accounting for 65 per cent of overall EVs sold last year. And in China, the cars that do a roaring trade tend to be cheap little runarounds. On top of that, consumers who do want the convenience of the high-end electric car have homegrown models to choose from: buffs reckon the Xiaomi SU7 is not entirely dissimilar to the Porsche Taycan, at a fraction of the price.

Price is also a factor in Europe, where luxury and premium EVs carry a relatively high premium compared to the equivalent internal combustion engine (ICE) model. Plus, the rapid pace at which EV technology is developing means that resale values are relatively low.

In the near term, sluggish demand for luxury EVs is only really a problem for western manufacturers who raced down that road. Porsche, for instance, has had to write down some of its investment. For those who have been keeping their options open, the slower than expected decline of the old technology means they can carry on selling the more profitable ICE cars for longer.

Still, it potentially stores up problems later on. For one thing, electrification may shrink the pool of customers that are willing to pay top dollar for a car: electric engines are less differentiated than the traditional kind, so manufacturers will have to figure out how to justify the extra expense via design and gizmos. And, for another, Chinese manufacturers are rapidly moving up the value chain. When the market for luxury EVs does ignite, western carmakers may find that rivals have raced ahead.

camilla.palladino@ft.com

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Europe’s leading wind turbine manufacturer, Vestas, has shelved plans to open its biggest factory in Poland, citing sluggish demand in its core European market.

Vestas announced last year that it would build the plant outside Szczecin, close to the Baltic Sea coast, to make blades used in powerful wind turbines.

However, the Danish group has now decided to suspend its investment in a facility that was initially expected to open in 2026 and employ more than 1,000 people.

The company told the Financial Times that the plans had been “paused due to lower than projected demand for offshore wind in Europe”.

It declined to say whether any of its other operations had been affected by the difficult market conditions in Europe, its key market.

The decision underlines the challenges faced by Europe’s offshore wind sector as it navigates higher costs, supply chain bottlenecks and political opposition in the US.

It is also a setback for Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s government and its efforts to cut Poland’s dependence on polluting coal by expanding in green energy and building domestic manufacturing for renewables.

The EU, UK and Norway have a combined offshore wind target of at least 129GW either operating or under construction by the end of the decade.

However, consultancy TGS 4C has said they are on track for only about 84GW, with Denmark and Germany both failing to find bidders for projects in separate auctions over the past 12 months.

European governments are trying to offer attractive terms and support to developers to help the industry, given its strategic importance as a source of low-carbon and domestically generated power.

But, outside China, the sector has struggled to generate returns, while attracting the ire of US President Donald Trump, who has a personal animosity towards the technology.

Ørsted, the world’s largest wind developer, recently outlined plans to retreat from the US and refocus investment in Europe and parts of Asia.

Turbine makers such as Vestas are generally keen to be certain of demand before investing heavily.

Yet any retreat by European manufacturers from their core market could open the door for Chinese competitors to move in and take market share.

Vestas said it “continues to invest in a local manufacturing footprint where offshore wind market volume and certainty allow”.

Offshore wind is central to Poland’s green efforts, with several projects under way that seek to turn the waters off Poland’s north coast into one of Europe’s largest hubs for wind farms.

Warsaw also hoped these can spur the creation of a domestic manufacturing sector capable of supplying turbines to a range of European markets.

Vestas has already invested in Poland by building an assembly plant for the nacelles that hold a turbine’s critical components and by buying a facility that makes blades for onshore turbines.

The planned Szczecin factory, however, was to be its largest Polish project to date, located on land bought in 2023. It was intended to manufacture blades for Vestas’s flagship offshore turbines, each capable of generating 15MW.

Poland’s first offshore turbines are expected to begin operating next year as part of the €4.7bn Baltic Power joint venture between state-controlled Orlen and Canada’s Northland Power, using Vestas as a supplier.

Warsaw wants Baltic Power and other large-scale projects to deliver 18GW of offshore capacity by 2040, roughly half of Europe’s current total.