To the best of our knowledge, no study has been conducted to assess the degree of student engagement in African medical schools using the AMEE ASPIRE criteria. The criteria define student engagement as participation in policy-making, program evaluation, extracurricular activity, and service delivery in both local and academic communities [23].

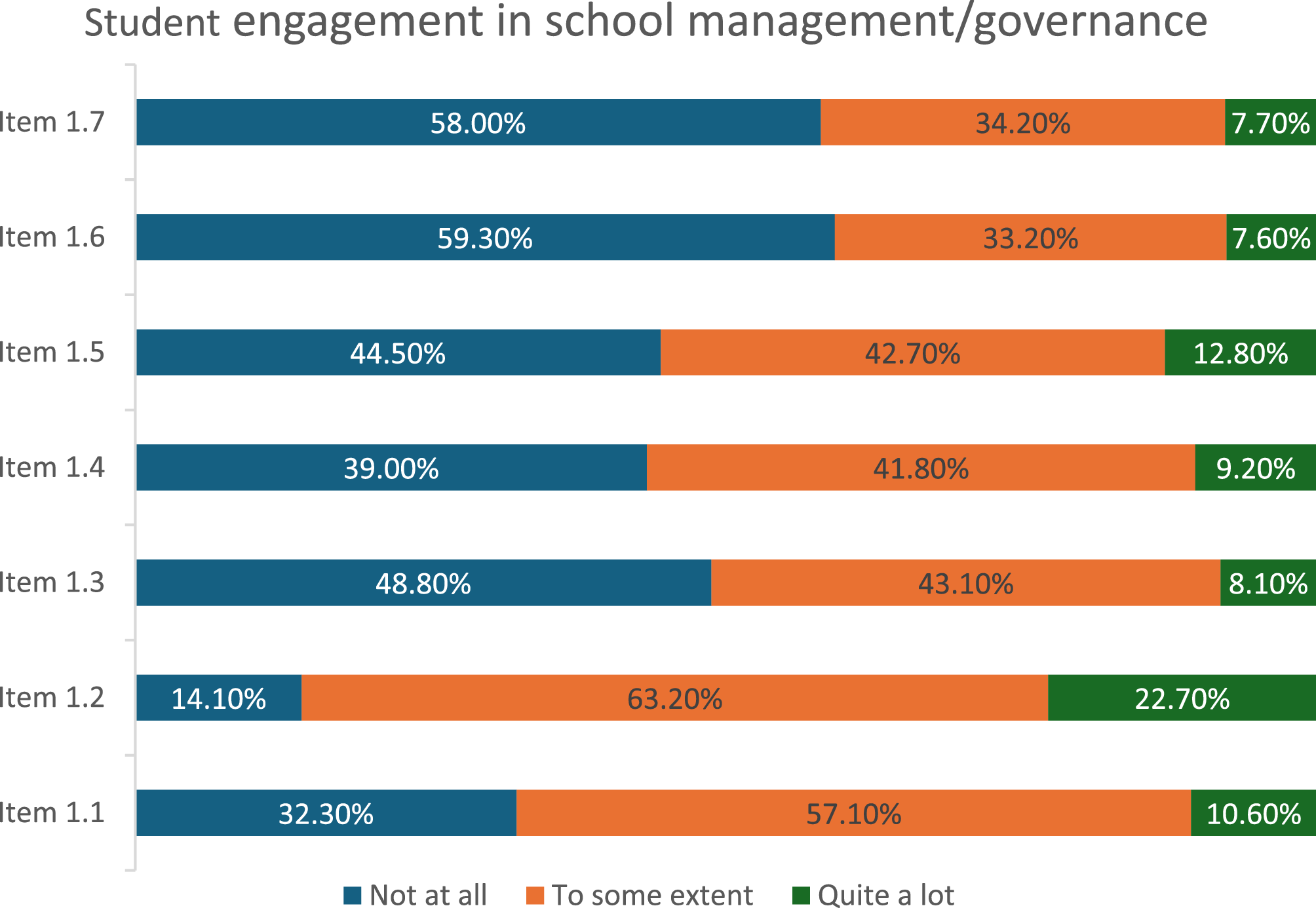

Student engagement in school management and governance

The survey of medical students across the University of Ibadan and the University of Ilorin found high levels of representation on school committees but lower perceived influence in learning processes, vision development, policy statement creation, accreditation, curriculum development, and staff development. This disparity may point to a dissonance between the structural implementation of student engagement and its actual impact in the surveyed schools. Interestingly, the current ASPIRE criterion for student committee representation not only requires proof of student presence on committees but also evidence of achievements made as a result of their active participation [23].

An analysis of the applications of 11 recipient schools of the ASPIRE award for excellence in student engagement showed that students constituted 50% of key committees and were trained for their roles in school governance [24]. While student representation on committees in the surveyed schools is commendable, the apparent lack of influence suggests that the absence of structured support, such as governance and leadership training, may undermine the potential impact of student involvement. This finding implies that without deliberate strategies to empower students beyond representation, institutions may inadvertently perpetuate tokenism, limiting the development of student leadership and hindering the realisation of the full benefits of participatory governance in medical education.

Student engagement in provision of school’s education programme

There is a markedly low level of engagement in curriculum evaluation, fairly compensated for by a higher, yet average level of feedback incorporation during curriculum development, active learning, peer teaching, resource development, mentoring, self-evaluation, and peer assessment. While peer support is highly encouraged by the ASPIRE criteria, it has been found to have a potentially negative underside in low-resource contexts [25]. Recent studies synthesising approaches to peer support in such settings suggest that limited resources may force unwilling students into roles ideally meant for professional intervention [25]. This dynamic raises ethical and sustainability concerns, as institutions may over-rely on students to compensate for faculty shortages, thereby shifting academic responsibilities onto learners rather than creating a structured support system. In contrast, students in ASPIRE awardee schools are financially compensated for peer tutorship, resource development, and mentorship of students requiring complex support [25]. This finding implies that in resource-limited educational environments, student engagement in academic support roles, if not properly structured, can unintentionally institutionalise a workaround for systemic inadequacies. This risk is particularly salient in Nigeria, where the mass emigration of healthcare workers, coupled with the widespread intention among medical students to emigrate, further strains institutional capacity [26]. Such patterns may compromise educational quality, blur role boundaries between faculty and students, and limit the long-term effectiveness of peer-led initiatives in fostering meaningful learning outcomes.

Student engagement in the academic community

Our study revealed a significantly high rate of student engagement in faculty-led research, with a comparatively lower, though still notable, level of participation in medical professional education meetings. This difference may reflect institutional structures that prioritise research involvement while lacking clear pathways or support mechanisms for students to participate in broader academic discourse, such as conferences and symposia.

In contrast, ASPIRE-awarded schools have formal mechanisms to support student participation in scientific meetings, including dedicated funding, opportunities for students to present at conferences, and the establishment of local research dissemination platforms. Pacific Island countries have even implemented innovative remote conference hubs to expand student access to international academic discussions at reduced cost [27]. The implication of this finding is that while research engagement may be well integrated into medical education in Nigeria, limited institutional support for research dissemination could constrain students’ exposure to critical skills in academic communication, networking, and professional development. Over time, this may lead to unequal academic trajectories between students in Nigerian medical schools and their global peers, ultimately affecting their competitiveness for postgraduate opportunities and contributions to the global health research ecosystem.

Student engagement in the local community, in extracurricular activities, and in service delivery

The perception of student involvement in local community projects, extracurricular activities, and healthcare delivery, both locally and during electives, was high across both institutions. However, as in the case of peer academic support, there is a pressing need to regulate the extent of student participation in healthcare service delivery to prevent institutional over-dependence on student labour. Without adequate oversight, medical students could be unintentionally integrated into the workforce as substitutes for healthcare professionals, undermining their educational experience and clinical training. To address this, institutions must strike a balance between clinical immersion and didactic instruction, ensuring that student participation remains a learning experience rather than a workforce necessity [28].

A comparable study applying the AMEE ASPIRE criteria was conducted at the University College of Medical Sciences, Nepal, with findings that contrast with our study. The Nepalese study reported poor perception of student engagement in institutional policy, vision, curriculum development, service delivery, and healthcare service during electives, whereas our study population reported higher engagement in these areas. However, faculty-led research engagement and participation in academic meetings were higher in the Nepalese study than in our findings [1]. This contrast underscores the importance of regional differences in structuring student engagement, as institutional priorities, funding models, and cultural contexts shape how engagement initiatives are implemented and perceived.

Student engagement across school and academic level

Our analysis revealed that preclinical students reported significantly higher engagement across several domains of the AMEE ASPIRE criteria compared to their clinical counterparts. These domains include school governance, self-directed learning, peer-led activities, and community engagement. Clinical students, in contrast, reported greater involvement primarily in faculty-led research. This disparity suggests a shift in the nature and intensity of student engagement as students progress through medical school. One possible explanation is the relative availability of time and institutional encouragement during the preclinical years, which may allow for broader participation in extracurricular and student-led initiatives. Conversely, the clinical years are typically characterised by more rigid schedules, high workload, and increased emphasis on clinical responsibilities, which may limit students’ capacity to engage in governance or community-based activities. Additionally, institutional culture may influence this dynamic, as governance and policy engagement structures may be more accessible or promoted in the earlier years of training. For instance, a study in South Asia found that clinical students were more burdened with service delivery demands, leading to reduced involvement in co-curricular and governance activities, whereas preclinical students had greater exposure to leadership and peer support structures (1). Similar contextual differences emerged when comparing institutions. While students from the University of Ibadan and the University of Ilorin reported broadly similar engagement levels, key differences were observed. Students from the University of Ilorin reported lower involvement in accreditation processes but showed stronger engagement in peer mentorship, local healthcare delivery, and participation in overseas electives. These variations may reflect institutional priorities, differences in mentorship structures, or variations in access to international programmes. The implication of these findings is that without deliberate scaffolding of engagement opportunities across both institutional contexts and stages of training, medical schools may inadvertently hinder students’ holistic development, particularly in the clinical phase.

Implications for medical practice and education

The findings of this study have several important implications for medical education and practice in Nigeria. While student representation in school management and governance structures was found to be relatively high, students reported lower levels of influence in key areas such as policy development, curriculum design, and staff promotion. This suggests that representation alone does not equate to meaningful engagement. For student participation to translate into genuine impact, medical schools must move beyond token inclusion and create mechanisms through which student voices can meaningfully shape institutional decisions. Such exposure can cultivate vital leadership and governance competencies in future medical professionals.

The study highlights strong student engagement in the delivery of the education programme, particularly in areas such as peer teaching, self-assessment, and self-directed learning. However, students were less involved in broader educational decision-making processes. This indicates a need to formally involve students in curriculum development and assessment design, thereby fostering a more collaborative educational environment and supporting the development of reflective, education-literate graduates who are better equipped to contribute to medical education reform in the future.

The high level of student participation in faculty-led research is encouraging, but the relatively lower engagement in academic meetings and dissemination activities points to a missed opportunity for academic growth. Medical schools should invest in systems that support students’ full participation in the academic community, including the provision of funding for research dissemination and conference attendance. By doing so, students can gain valuable experience in scientific communication and build networks that enhance their academic and professional development.

The findings reveal a commendable level of student involvement in community service, extracurricular activities, and healthcare delivery. While this reflects a strong sense of social responsibility among students, there is a risk of institutions becoming overly reliant on student labour in service delivery. Without appropriate oversight, such reliance could compromise students’ educational experiences and blur the boundaries between learning and workforce responsibilities. Institutions must ensure that community-based learning remains appropriately structured and that students are supported to learn rather than to substitute for healthcare professionals.

The variation in engagement between clinical and preclinical students suggests that opportunities for meaningful participation may diminish as students progress through their training. Preclinical students were more likely to report higher engagement across several domains, raising concerns that the intensity of clinical responsibilities may limit opportunities for active involvement in governance, peer learning, and extracurricular activities. Medical schools should consider tailoring engagement strategies to different stages of training, ensuring that clinical students also have structured avenues to participate and lead in ways that complement their clinical learning.

Strengths

This is a novel study; the first to apply the AMEE ASPIRE criteria to African medical education. It assessed a robust, representative sample of medical students in two medical schools, using a globally recognised tool with high internal reliability. The AMEE ASPIRE framework enables assessment of student engagement across multiple domains, ensuring a well-rounded assessment of the different facets of student participation.

Limitations

This study uses only a quantitative approach to gather data. The absence of qualitative data limits insight into the state of student engagement in these institutions. Also, this study was administered at only federal government-owned medical schools. Therefore, the results may not be generalisable to state-owned and private institutions as the administrative contexts may differ.