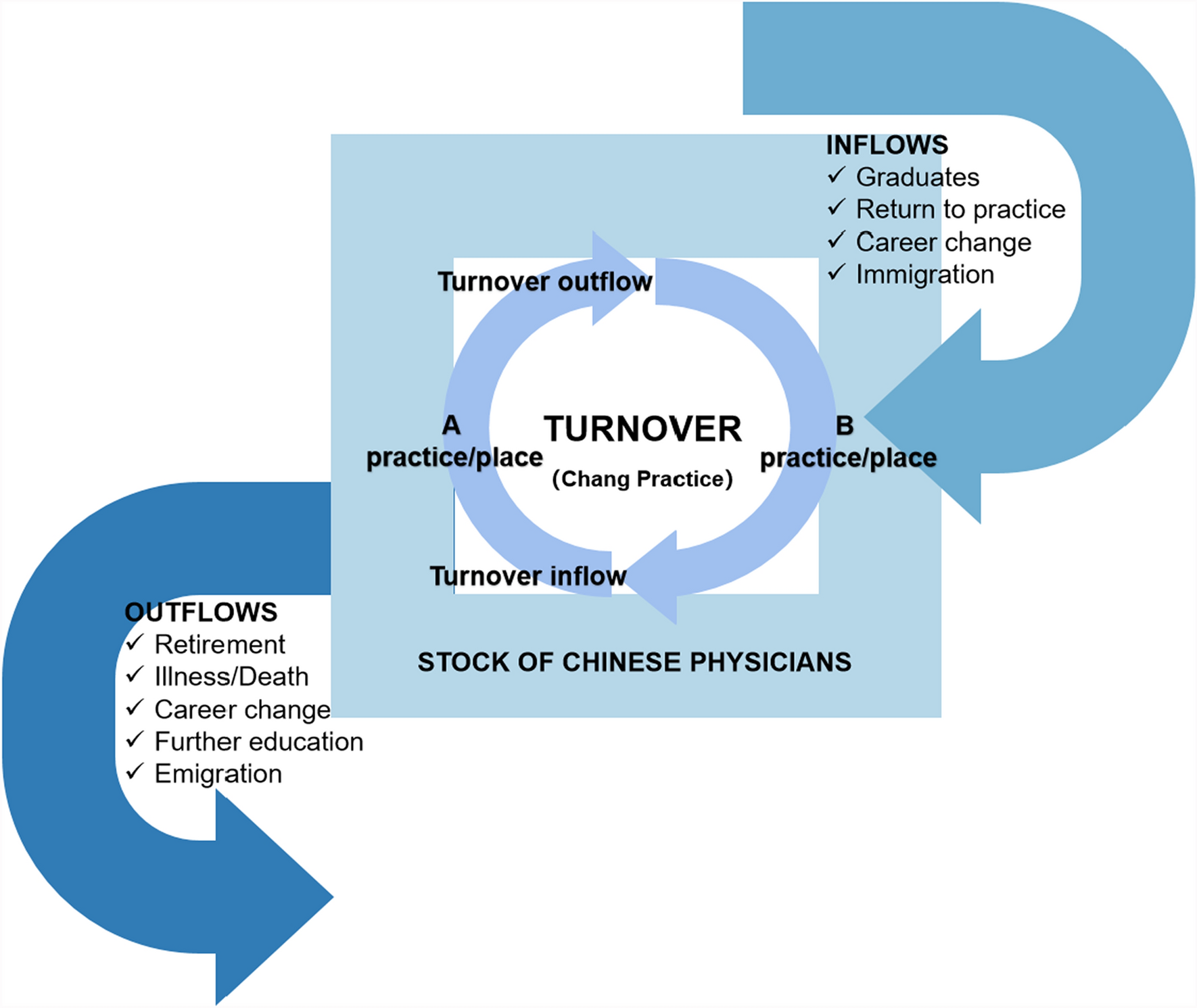

Using data from nearly 3.7 million Chinese physicians spanning 11 years, we found that between 2011 and 2021, 19.4% of physicians changed workplace at least once, and the national annual physician turnover rate increased from 1.6 to 4.4%. Geographically, physician turnover in China tended to favor more economically developed regions, such as the eastern region, urban areas, and provincial capital cities. Institutionally, physician turnover between different types of institutions demonstrated reciprocal exchanges with nearly balanced volumes, but there has been a growing appeal for primary care physicians. Younger physicians, those with higher degrees, and those with senior professional titles were more likely to change their workplaces. Non-permanent employment contracts, lower income, heavy workload, and working in rural areas or for a primary care institution were also risk factors for physician turnover.

Given the limited nationwide research on physician turnover, we identified only one study applied comparable definition of turnover in U.S. reporting national physician turnover rates using Medicare billing data, which increased from 3.7% (2010) to 4.2% (2020). Since 2014, the rate stabilized above 4%, peaking at 4.3% in 2018 [24]. This study reported similar level of national turnover rate but a more significant increase over the past decade. According to a previous survey conducted in 2013 across 11 western Chinese provinces, approximately 29.1% of the 5046 rural health workers indicated intentions to leave [25]. Their results were higher than our finding of 19.4%, which can be attributed to the fact that turnover intentions are generally higher than actual turnover [26]. Furthermore, their study participants came from the western region and rural areas, which were found to have higher turnover risk in this study. Monitoring the long-term dynamics of physician turnover in China is necessary to determine whether the rate will continue to rise or stabilize and whether it will be influenced by relevant policies.

Our analysis identified increased NTR in primary care institutions. In comparison, a survey of Chinese primary care physicians in 2005 reported that over 8% of health workers left primary care institutions annually, with the majority moving to higher level healthcare facilities [27]. Such improvements were most likely attributable to China’s substantial investments in primary care institutions in underserved areas [17]. Our findings indicated that economically developed regions, such as eastern China and urban areas, demonstrated stronger attractiveness to mobile physicians, which is consistent with research findings from other countries. A 2015 study of Australian general practitioners found a net turnover trend toward major cities [28], while another investigation into Australian primary care physician retention also identified remoteness as a critical factor influencing workforce turnover [29]. Similarly, a nationwide study of all general practices in the UK between 2007 and 2019 revealed that practices in the most deprived areas had higher turnover rates [30]. In terms of the direction of turnover, the overall physician mobility is relatively consistent with the population flow. According to the national population census data released by China, from 2010 to 2021, the proportion of urban population increased by 14.2 percentage points. Guangdong province is the largest province in terms of physician turnover inflow and has also experienced a population increase of 21.7 million over the past decade. The northeast region, as a major turnover-outflow area, has seen a population decrease of 11.0 million.

Our findings indicate that 14.4% of physician turnover occurred between provinces during the study period, although this proportion is increasing. Similar patterns have been observed in studies from Australia, with just 10% of physician mobility occurring across states [28]. Besides, between 2011 and 2021, while some provinces experienced net turnover losses, the total number of physicians and physician density in all provinces of China increased significantly [16] due to substantial physician inflows during this period. Therefore, current physician turnover is unlikely to have a significant impact on the geographic distribution. However, future studies should quantify such impacts to mitigate potential adverse effects. In addition, given the declining trend in physician inflows, physician turnover may increasingly influence geographic distribution in China in the future.

This study also discovered several turnover circuits in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration, the Sichuan–Chongqing urban agglomeration, and the Yangtze River Delta region (Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui), which align to China’s regional coordinated development strategies [13]. These areas exhibit geographical proximity but disparities in socioeconomic development levels and medical service capacity. Under the framework of these strategies, standardized professional title evaluation systems and unified social security policies have been implemented across regions, ensuring continuity in benefits for mobile physicians and effectively reducing institutional barriers to talent exchange. Notably, regional collaborations have been significantly enhanced, such as jointly established regional medical centers and delivered telemedicine care, which may encourage the formation of turnover circuits. For instance, elite medical hubs in Beijing and Shanghai that construct regional medical centers usually require physicians to undertake rotational assignments of months in partner regions (e.g., Tianjin, Anhui), exposing them to the professional and living environments of less-developed areas, which has been found to be positive factor to foster the willingness to relocate and practice in underserved regions [31]. Conversely, physicians in less-developed areas gain access to joint training programs and academic exchanges, improving job satisfaction while creating pathways for career advancement to higher tier institutions. However, further research is needed to investigate the turnover patterns within these circuits, as well as the mechanisms for addressing or exacerbating the imbalanced allocation of medical resources.

This study explored the factors that influence physician turnover in China and found that younger physicians, those with higher levels of education, senior professional titles, lower income, and heavier workloads, as well as those working in rural areas or primary care medical institutions, were more likely to leave their current jobs. Previous studies on the factors influencing physician turnover in individual provinces in China or other countries [30, 32, 33], as well as studies on the factors influencing physician turnover intentions [11, 12, 34], have yielded similar results. Over the past decade, physician turnover in China has been characterized by competition for highly educated and senior professional-level talents in developed regions. Non-permanent employment contracts were found to be an important risk factor for physician turnover in this study, which is consistent with the findings of a study conducted in Hubei, China [35]. Physicians with permanent employment contracts are more likely to feel a greater sense of belonging and are more loyal to their workplace.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report turnover among 3.7 million Chinese physicians across the Chinese mainland over an 11-year period. We developed a cohort based on individual-level data, allowing us to not only quantify the level, trajectory, and characteristics of Chinese physician turnover but also to identify individual and institutional factors that influence physician turnover. However, this study has limitations. First, we define turnover rate as the first recorded job change between 2011 and 2021, ignoring job changes that some physicians may have experienced prior to 2011. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that physician turnover prior to 2011 was likely to be low and had little impact on our results. Second, although CHSI requires institutions to update physician information, such as education and professional titles on an annual basis, some institutions may fail to keep up with changes in a timely manner, potentially underestimating the proportion of physicians with higher education levels and senior professional titles in the retention group. However, as more medical institutions use the data collection system for personnel management, and many provinces use it as a qualification check for professional title evaluation, the impact of this issue on our results is being mitigated. Third, the lack of physician turnover causality data prevents differentiation between voluntary (e.g., career transitions) and involuntary turnover (e.g., layoffs), which, however, might require distinct policy interventions. Fourth, the data we used is collected for government management purposes and reported by institutions, with little information on individual physician characteristics, such as marital status and families, which could be potential confounding factors. Fifth, due to limited access to related data, we could not integrate social factors such as population mobility, demographic shifts, and regional healthcare demand patterns into consideration, which would have further enhanced the policy relevance of our findings.

In summary, China is experiencing a rising turnover rate. Future policies should pay more attention to central, northeastern regions, and rural areas while continue strengthening the primary care physician workforce. Effective intervention may prioritize young professionals and senior experts by ensuring competitive salary packages, and controlling work-related burnout—measures proven effective by multiple studies [36]. Although current mobility patterns may not yet significantly impact overall distribution, continuous monitoring is necessary to guide physician turnover. If physicians continue to concentrate in developed regions, it may increase the fiscal load on healthcare systems and reduce operational efficiency [37]. This study also aims to provide an actionable solution for monitoring nationwide physician mobility by longitudinally linking individual-level administrative data, potentially addressing research gaps in other countries. Finally, updated health workforce data are crucial for understanding the dynamic changes in medical human resources. This will support evidence-based policy advocacy, scientific workforce planning, and effective governance at the regional, national, and global levels.