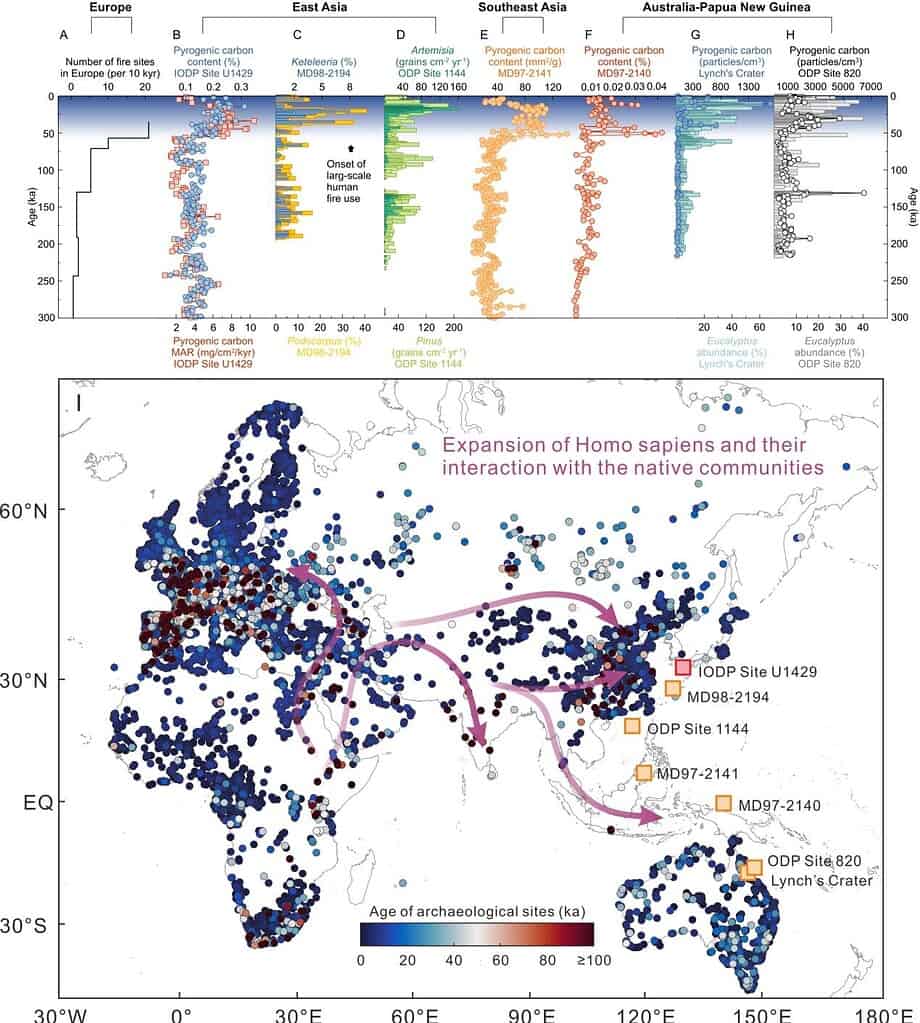

A new study reveals that humans were extensively using fire to modify landscapes as far back as 50,000 years ago. That’s at least 10,000 years earlier than previously believed. Scientists uncovered this clue in a 300,000-year-old sediment core extracted from the East China Sea.

The core contained fossilized charcoal, microscopic remnants of plant matter burned but not fully consumed. Known as pyrogenic carbon, these particles drifted into the sea via rivers over tens of thousands of years. They serve as an enduring record of fire on land.

A Fire Signature That Outpaced Climate

The research team, led by Dr. Debo Zhao from the Institute of Oceanology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, found something unexpected. Around 50,000 years ago, levels of pyrogenic carbon suddenly spiked. The timing didn’t line up with known climate patterns. It suggested something new was at play.

“Our findings challenge the widely held belief that humans only began influencing geological processes in the recent past—during the last Ice Age and the ensuing Holocene,” said Dr. Zhao.

Instead, the evidence points to humans (modern Homo sapiens) as the likely culprits. This timeline aligns with archaeological records showing a rapid expansion of Homo sapiens across Eurasia, Southeast Asia, and into Australia between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago.

In each of these regions, fire activity began to rise dramatically. But this wasn’t wildfire season. These were intentional flames.

A Record of Ice and Fire

As the climate cooled during glacial periods, fire became indispensable. It helped early humans cook food, stay warm, fend off predators, and migrate into colder, more challenging landscapes. But it also transformed those landscapes.

“Humans likely began shaping ecosystems and the global carbon cycle through their use of fire even before the Last Ice Age,” said Dr. Stefanie Kaboth-Bahr, a paleontologist at Freie Universität Berlin and coauthor of the study.

The fire’s effects were lasting. Burning vegetation releases carbon into the atmosphere. Doing this repeatedly over large areas eventually warms the planet, albeit by a very tiny amount compared to present-day industrial activity.

The discovery suggests that humans began influencing the Earth’s carbon cycle tens of thousands of years earlier than scientists had assumed. “Even during the Last Glaciation, the use of fire had probably started to reshape ecosystems and carbon fluxes,” added Professor Wan Shiming, another corresponding author.

The Global Signature of Humanity’s First Flames

The researchers compared the East Asia findings with data from Europe, Southeast Asia, and Papua New Guinea–Australia. The same pattern emerged in each region: a sudden uptick in fire activity starting roughly 50,000 years ago.

Crucially, this fire surge appeared even where natural conditions—like rainfall or lightning—wouldn’t account for such increases. Something else had to be driving it. The clearest candidate: humans.

The study also suggests that this early fire use was systematic enough to leave a lasting mark on Earth’s geological record—what some scientists refer to as the pyroscape, the legacy of fire through time.

This study underscores how early and profoundly humans began altering the planet. It challenges the idea that the Anthropocene (our proposed new geological epoch) begins with agriculture or the Industrial Revolution. Instead, the spark might have been struck much earlier, with the simple but powerful act of lighting a fire.

Kaboth-Bahr’s research is part of a larger initiative called The Burning Question, which investigates the role of fire in shaping ecosystems across Eastern Africa. Supported by the German Research Foundation and partners in Ethiopia, the project seeks to understand fire’s ecological, climatic, and cultural significance over the last 600,000 years.

The findings appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.