While Huntington’s disease (HD) primarily affects the brain, the genetic change that causes the disease is present in every cell throughout the body. Because of that, it has influences beyond the brain, including in the gut. Increasing evidence suggests that changes in gut microbes, leaky barriers, inflammation, and nerve signaling may contribute to HD progression. A recent review of published research maps the “gut–brain superhighway” in HD, highlighting where traffic flows smoothly, where it’s blocked, and where detours might offer new treatment options.

How Human Are You, Really?

If someone were to ask you what species you see when you look in the mirror, you would undoubtedly say human. But people are actually made up of more microbes than anything else. Shockingly, there are more microbial cells in your body than human cells. And 99% of the genetic material in your body is from microbes – only 1% of your DNA is of human origin! So it makes sense that when we think about human biology, we should seriously consider the role that microbes play in our health.

Microbes are microscopic organisms, like bacteria, viruses, fungus, or yeast. When we think of such things, we typically think of infections, but most microbes are harmless, and even helpful. The various microbes that live in our gut help us digest various foods, aid with nutrient absorption, and work to develop our immune systems. Increasing evidence also suggests that the gut, and the microbes that live there, can impact brain health.

The gut is so closely tied to the brain that some scientists call it the “second brain”. This is because there is an extensive network of neurons within our gut that directly communicates with the brain through the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve is the main connection that controls the parasympathetic nervous system. Think of your parasympathetic nervous system as controlling “rest and digest” functions. It helps to regulate digestion, heart rate, and our immune system.

From the Brain to the Belly: Why the Gut Matters in HD

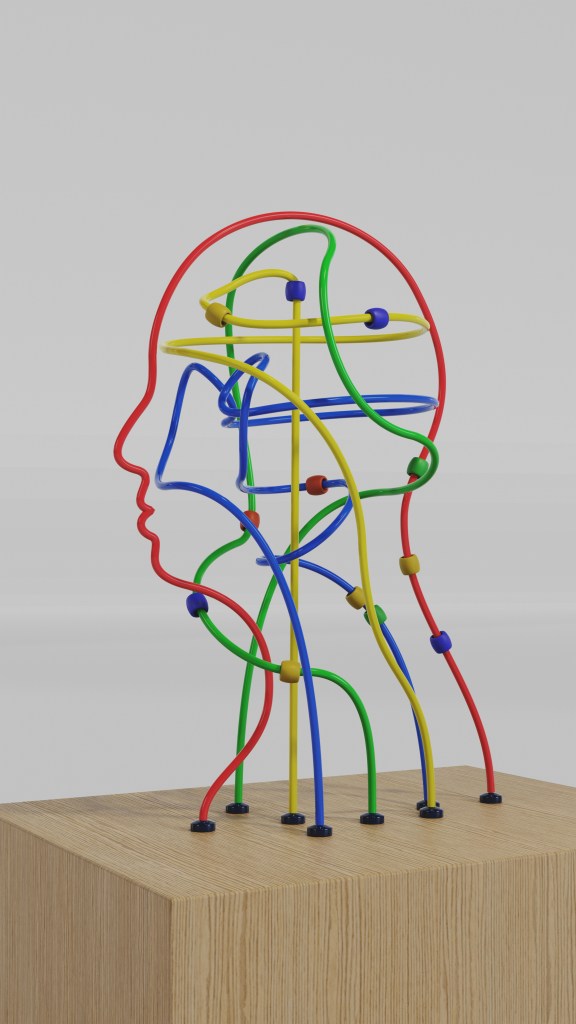

We tend to picture HD as a one-way street, where the gene that causes HD produces a faulty protein that causes a decline in brain health. But it’s more like a two-way superhighway with lots of back and forth between the brain and the rest of the body, especially between the brain and the gut, referred to as the “gut-brain axis”.

This road is busy with traffic lanes like the vagus nerve, immune cells, and the “second brain” of the gut. There are vehicles carrying chemical messengers made by gut microbes and border checkpoints such as the gut lining and the blood–brain barrier, which should only let safe travelers through.

In HD, problems at almost every point on this route can slow traffic, let dangerous cargo through, or disrupt communication entirely.

Roadwork and Weak Bridges: Barriers Breaking Down

HD’s faulty protein, expanded huntingtin (HTT), isn’t just in the brain, it’s everywhere, including the gut. This widespread presence may contribute to why people with HD often have symptoms in parts of their bodies beyond the brain, including gastrointestinal problems like chronic diarrhea, constipation, incontinence, and poor nutrient absorption.

Two major “bridges” on our superhighway are affected – the gut barrier and the blood-brain barrier. The gut barrier can become “leaky,” letting microbes or their components escape into the bloodstream. There is some evidence for this in people with the gene for HD before and after they start to show symptoms, seemingly at levels comparable to those in inflammatory bowel disease.

The blood–brain barrier also shows signs of “loosened bolts” in HD, with fewer tight junction proteins holding it together. When both bridges are compromised, harmful substances from the gut could have a clearer route to the brain. Supporting this possibility, traces of bacterial and fungal DNA have been found in the brains of people with HD after death. While contamination is possible, it suggests that microbes, or at least parts of microbes, might be able to cross compromised barriers of the gut and brain.

Traffic Jams: Inflammation Along the Route

The gut is the body’s largest immune organ. In HD, this immune system seems stuck in overdrive, like a traffic jam of inflammatory signals. Cytokines, which play a role in regulating the immune response and inflammation, seem to be present at increased levels in blood from people with HD, years before symptoms start. Adding to that, higher levels of some cytokines appear to be linked with worse symptoms and lower scores that chart someone’s ability to carry out day-to-day tasks.

But encouragingly, it seems that some beneficial gut bacteria may be able to dampen this inflammation, acting like traffic police to keep things moving. However more work is needed to understand the exact type of bacteria that could provide a benefit and if we could harness this as a future treatment option for people with HD.

Inflammation is also seen inside the gut itself, with high levels of a biomarker that signals stress on the gut lining.

Faulty Signaling: Vagus Nerve Disruptions

The vagus nerve is the main fiber-optic cable of the gut–brain superhighway. It carries both sensory updates from the gut to the brain and calming “anti-inflammatory” signals back down. In HD, low vagal tone, a sign of reduced nerve activity, seems to be present even 20 years before motor symptoms.

Low tone could worsen inflammation and has been linked to depression, a common symptom of HD. Researchers are asking whether stimulating the vagus nerve could one day be a therapeutic on-ramp.

The Microbial Passenger List: Who’s in the Vehicles?

Studies are suggesting that the gut microbiome in HD has a different passenger list than in healthy individuals. Diversity may be lower, meaning fewer types of microbes, and certain species might be missing or reduced. Less diversity in the gut microbiome has been linked to lower immune function, poorer digestion, and fatigue.

While more work is needed, researchers are starting to tease apart the microbial differences in the gut of people with HD. For example, the presence of certain microbes may be linked to better thinking skills but worse motor symptoms. And there appears to be sex-specific differences in both humans and mice, suggesting men and women may have different microbes present.

Possible Road Repairs: Interventions in the Works

If the gut–brain superhighway in HD has traffic jams and potholes, the big question is, can we fix it? Scientists are exploring various ideas to get traffic flowing more smoothly. One option is probiotics (adding “good” bacteria) or prebiotics (feeding the good bacteria already there). These are generally safe, but the first HD trial testing probiotics didn’t show big changes in gut health or thinking skills, so more work is needed in this area to know if this might be beneficial. It might be that we need longer treatment or different combinations of probiotics are needed to see an effect.

Food itself could be a powerful repair tool. In HD mouse models, a high-fiber diet seemed to boost thinking skills, lift mood, and improve gut health. But the most striking findings from this study compared a high-fiber diet to a no-fiber diet in mice, which isn’t realistic for people, who are more likely to consume a low-fiber diet by comparison. So more work would be needed to test this theory.

In people, following a Mediterranean-style diet that is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats has been reported by some to improve quality of life and perhaps allow for fewer movement problems. Other diets, like the ketogenic (very low-carb, high-fat) approach or intermittent fasting, have shown mixed results and come with serious risks. It’s a reminder that there’s probably no one-size-fits-all diet for HD.

It’s not just about food, how we live also shapes the gut–brain connection. In HD mice, physical activity and a stimulating environment seem to delay disease onset and slow progression, while also changing the gut microbiome. Even certain antibiotics, if chosen carefully, have shown reduced inflammation and protected nerve cells in lab models. But broad-spectrum antibiotics, the kind that wipe out a wide range of bacteria, can cause long-term damage to gut diversity, so they’re not a realistic option for intervening with the microbiome.

An Overlooked Exit: Oral Health

After the gut, the mouth has the second largest microbial population within the body. While the effect of HD on the microbes in the mouth hasn’t been studied, we do know that as HD progresses, it can become harder to keep up with oral hygiene. This can lead to gum disease, cavities, and inflammation in the mouth.

That might sound like a small problem compared to the challenges of HD, but oral health affects the whole body. Inflammation from the mouth can spill over into the bloodstream, adding to the overall “traffic jam” of inflammation we already see in HD. Over time, this could make gut and brain problems worse.

The good news is that this is an area where we already have easy tools. Regular dental care, help with brushing and flossing, and even specially designed oral probiotics could all help keep the mouth’s microbial community balanced. These simple steps might not just improve comfort and quality of life, they could also help reduce inflammation that feeds into HD’s wider effects.

It’s a reminder that in a complex condition like HD, the most effective “road repairs” might come from surprising places. From the microbes in our gut to the health of our mouth, every stop along the gut–brain superhighway could hold clues, and opportunities, for improving life with HD.

Summary

- The gut–brain axis is a busy two-way superhighway of nerves, immune cells, and chemical messengers.

- In HD, barriers leak, inflammation surges, and microbial balance shifts, potentially influencing disease progression.

- Early studies suggest diet, probiotics, or exercise could one day help, but more research is needed.

- Oral health may be an underexplored but important off-ramp in managing HD’s systemic inflammation.

Learn More

Original research article, “The microbiota–gut–brain axis in Huntington’s disease: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic targets” (open access).