Microscopic photorealistic image of thyroid cancer cells – Generated with Google Gemini AI

New data from the IoN trial, a landmark phase 3 randomized study, provides compelling evidence that postoperative radioiodine ablation can be safely omitted for a substantial portion of patients with low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer.1,2 The findings, published in The Lancet, mark a significant step toward deescalating therapy and reducing patient burden for this common malignancy.

Study Rationale and Design

While radioiodine ablation has long been a standard component of postoperative care for many patients with thyroid cancer, its necessity has been increasingly questioned, particularly for those with a low risk of recurrence. The IoN study, a multicenter, noninferiority trial conducted across the United Kingdom, was designed to directly address this clinical uncertainty.

Researchers enrolled 504 patients with low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer, defined as those with pT1 or pT2 tumors and no evidence of nodal involvement (N0 or Nx). Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive ablation or no ablation. The study’s primary objective was to determine if avoiding radioiodine ablation was noninferior to receiving it, as measured by the 5-year recurrence-free rate.

The trial’s noninferiority design is critical for clinical practice, as it sought to prove that a less aggressive approach was no worse than the current standard. This is a powerful statistical framework for evaluating deescalation strategies.

Key Findings and Clinical Implications

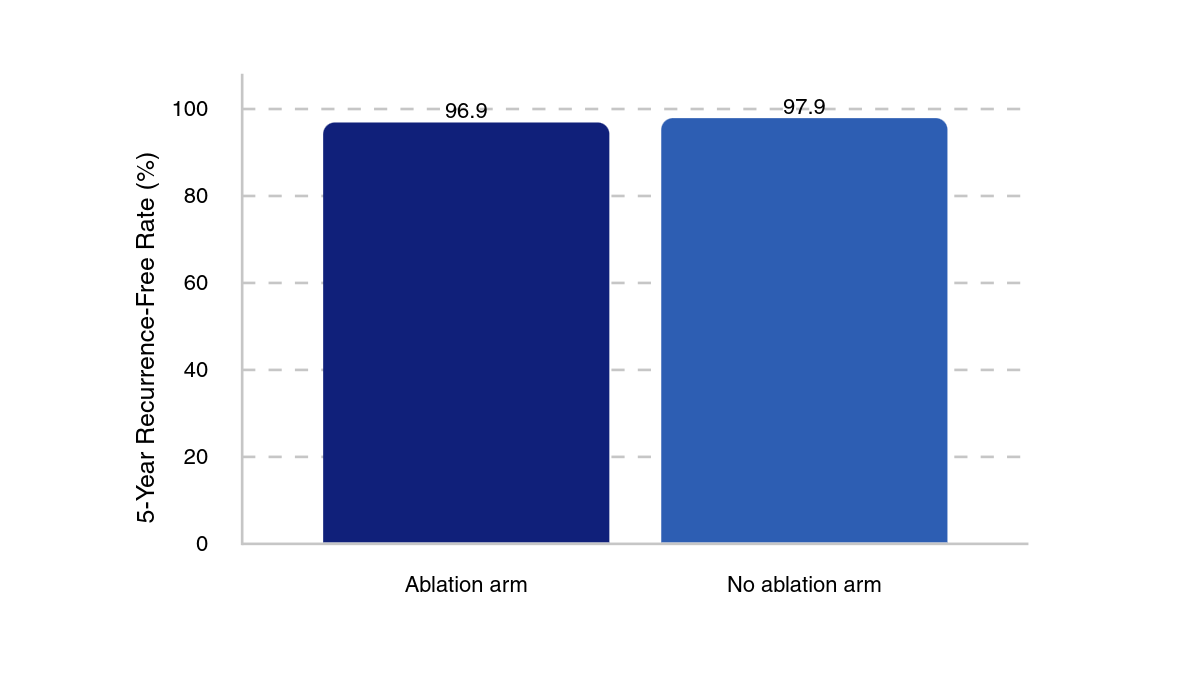

5-year recurrence-free rates

With a median follow-up of 6.8 years (IQR, 5.6–8.6) in the no ablation group and 6.6 years (IQR, 4.8–8.5), there were 8 recurrences in the no ablation group vs 9 in the ablation group. These corresponded to 5-year recurrence-free rates of 97.9% (95% CI, 96.1%–99.7%) and 96.9% (range, 94.7%–99.1%), respectively. Recurrence rates were higher in patients with pT3 or pT3a tumors, with 9% (n = 4/46) of overall patients with pT3 or pT3a tumors experiencing a recurrence vs 3% (n = 13/458) in patients with pT1 or pT2 tumors.

Adverse events (AEs) were similar between arms, with the most common AE being fatigue (25% in the no ablation group vs 28% in the ablation group), lethargy (14% vs 14%), and dry mouth (10% vs 9%). Further, there were no treatment-related deaths.

This is a notable development for the seventh most common cancer type globally, as it means patients can be spared the side effects associated with radioiodine, which can include salivary gland damage, dry mouth, and an increased risk of secondary malignancies. Furthermore, avoiding ablation eliminates the need for hospitalization and the logistical complexities of managing a radioactive substance, which can be a significant psychological and financial burden for patients.

These findings build upon a growing body of evidence. Previous trials like ESTIMABL1 and HiLo demonstrated that a lower dose of radioiodine was noninferior to a higher dose. The ESTIMABL2 trial further suggested that ablation could be avoided in certain patients. The IoN study expands on this by including patients with pT2 tumors, providing a broader evidence base that supports a more conservative, risk-stratified approach to postoperative management.

The trial was not powered for subgroup analysis, and therefore, clinical judgment and established guidelines should still be followed for these higher-risk groups.

“Studies are ongoing to refine the risk of N1 disease, and until they are published, clinicians should continue their current practice for treating pT3, pT3a, and N1a disease,” study authors noted. “Some clinicians will prefer to still offer ablation to these patients, but in some circumstances—for example, if patients with N1a disease have low or undetectable thyroglobulin concentrations and no adverse tumour features—not giving ablation could be considered along with close monitoring.”