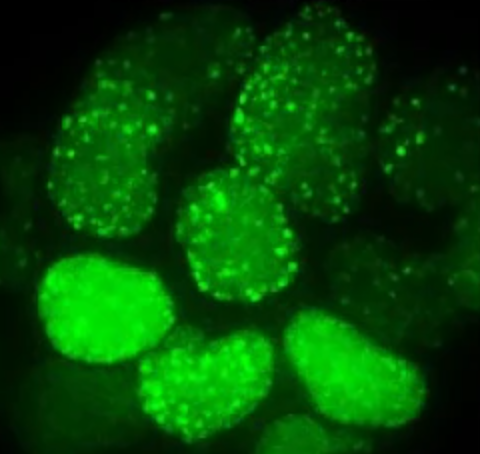

In a quiet lab at Utrecht University, researchers have built a tool that lets you watch one of life’s most serious crises unfold in real time. Inside every cell, DNA breaks, repairs, and sometimes fails to heal. Until now, you could only see…

In a quiet lab at Utrecht University, researchers have built a tool that lets you watch one of life’s most serious crises unfold in real time. Inside every cell, DNA breaks, repairs, and sometimes fails to heal. Until now, you could only see…