Authors: Martin Barrett1 and Jeffrey R. Farr2

1Department of Recreation and Parks Management, Frostburg State University, Frostburg, MD, USA

2Department of Hospitality and Sport Management, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, USA

Corresponding Author:

Martin Barrett

101 Braddock Road

Frostburg, MD 21532

[email protected]

301-687-4475

Martin Barrett, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Sport Management at Frostburg State University in Frostburg, MD. His research interests focus on the emergence and development of non-traditional sports.

Jeffrey R. Farr, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Sport Management at The University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, AL. His research interests focus on understanding the relationships between families and youth sport participation.

Exploring varsity sport readiness in college cricket: A content analysis of the stated purpose of existing college cricket clubs

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to explore the readiness of cricket to be elevated from the auspices of student-run structures on university campuses to the varsity level. To do so, a content analysis of college cricket club purpose statements was conducted to establish why such groups facilitate cricket activities. Content from 35 publicly accessible college cricket club constitutions was collected and the textual data analyzed using a process of emergent coding. The results of the content analysis established increasing awareness of and interest in cricket and bringing people together as the two most frequent purpose statements within the sampled college cricket clubs. Furthermore, a purpose typology based on three dimensions – performance, participation, and promotion – was created by aggregating the discreet statements into likeminded themes. Just over two-thirds of the sample disclosed performance as part of their purpose, which points to how most college cricket clubs are organized around competition and performance; thus, demonstrating an assumed readiness for, or at least alignment with the emphasis of, varsity-level athletics. However, campus recreation professionals supporting college crickets should recognize how these groups often have a multi-faceted purpose that extends to participation and promotion, which means college cricket clubs are well-placed to play a central role in popularizing the sport in the United States, as well as contributing to institution-level priorities such as student recruitment and retention.

Key words: college sport, club sport, cricket, purpose statements, sport development

INTRODUCTION

Cricket is a fast-growing sport in the United States. Today, there are more than 200,000 playing cricketers in America, double that in New Zealand (34). There are also now an estimated 10 to 20 million cricket fans across the country (37). Moreover, revenue in the US cricket market is projected to reach $90 million this year (34). Much of this growth is arguably attributable to the establishment of a sustainable professional men’s cricket tournament – Major League Cricket – which started in 2023, as well as the United States co-hosting the 2024 International Cricket Council T20 World Cup alongside the West Indies. Cricket is also set to be featured in the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028. Another salient factor in the growth of cricket stateside is the “transformative influence of South Asians, who, with their unwavering passion and dedication, have brought their love and expertise of cricket to these regions from their home nations” (17). For instance, as of 2022 the United States was home to about 4.8 million Indian Americans (30).

At US colleges and universities, cricket exists at the sub-varsity level in the form of club sports, student organizations, and intramural activities. The exact number of colleges and universities boasting active cricket clubs is unclear. In 2017, American College Cricket – the then governing body of the sport at the collegiate level – claimed to have 70 member colleges across both the United States and Canada (2). Yet, college cricket in the United States has a rich history. Notably, robust cricket competition existed on the campus of Haverford College from the early 1850’s with the college competing in one of the first reported intercollegiate contests against the University of Pennsylvania in 1864 (15). The first intercollegiate cricket governing body was established in 1881 when the University of Pennsylvania, along with four other institutions – including Haverford College, formed the Intercollegiate Cricket Association (25).

More recently, however, a new governing body came to the fore – the Collegiate Cricket League (CCL). In December 2024, the CCL announced a first-of-its-kind 10-over tournament to take place in Spring 2025 culminating with national finals, $50,000 in available prize money for teams, and a coveted trophy (28). Furthermore, the tournament is set to rival the global exposure of the NCAA (28). CCL’s strategy is built on a desire to establish cricket as a varsity sport at US colleges and universities through the investment of media and sponsorship revenues that will enable schools to offer scholarships and invest in state-of-the-art facilities (28).

Elevating college cricket to a varsity sport – albeit outside the purview of the NCAA – raises important questions about the current structures and systems of organized cricket on college campuses and, therefore, the readiness of a critical mass of institutions to make this leap. Varsity-level college sport in the United States is a cultural phenomenon. Intercollegiate athletic departments articulate through their mission statements the intent to achieve both academic and athletic excellence (40). However, intercollegiate athletics also serves a plethora of additional purposes including positive contributions to increased enrollment, increased national exposure, and strengthened ties to alumni and the university community (29). Certain aspects of varsity and club sport programs at the college level are alike. For instance, college sport clubs have performance or competition-based goals (7). Moreover, Warner, Dixon, and Chalip (41) describe how both sport contexts bring together individuals with common interest in sport and provide avenues to develop elite athletes. Also, club sport participants experience growth through their extra-curricular involvement – mostly through gains in leadership skills, time-management, and school pride associated their roles as club sports leaders (11). However, distinct differences exist between the purpose of varsity and club sport programs. As examples, college sport clubs have administrative goals such as increasing participation numbers, as well as social goals such as network building (7). In this way, club sport shares similarities with student organizations, which “create opportunities for leadership development, learning, student engagement, and fostering of shared interests” (43). Student organizations exist in multiple forms including – but not limited to – academic organizations, community service organizations, and multicultural organizations (10). Importantly, sporting activities on college campuses are governed through all three systems: varsity sport, club sport, and student organizations.

While the vision of CCL is ambitious, the increasing popularity and growing demand for cricket means the sport is seemingly well-placed to make further breakthroughs in the evolving landscape of college sports. The purpose of this research is to understand the current state of organized cricket structures on US college and university campuses. Specifically, this research is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. For what purpose(s) are organized cricket activities facilitated on US college campuses?

RQ2. To what extent do the purpose(s) of the groups facilitating organized cricket activities differ based on their classification?

In answering these research questions, inferences are then made on the potential synergy between existing college cricket activities and possible future varsity-level college cricket activities. Thus, the outcome of this research is to provide an assessment of the short-term readiness of college cricket to become elevated as a recognized intercollegiate varsity sport, which has implications for not only those who organize such activities on campus but also those who govern the sport.

METHODS

Research Design

This research adopted a qualitative research design with a goal to elicit a “comprehensive summarization, in everyday terms, of specific events experienced by individuals or groups of individuals” (22). The method used to achieve this goal was a document content analysis. In broad terms, content analysis is the analysis of the content in a message where the message forms the basis for drawing inferences and conclusions about the content (27, 31). The central premise of content analysis is to distil words into fewer content-related categories (9).

Data Collection

As previously mentioned, the exact number of colleges and universities boasting active cricket clubs is unclear. Therefore, the first step within the data collection process was to establish a current baseline of active college cricket clubs (i.e., the total population). To complete this initial step, an extensive multi-pronged search of secondary data sources was conducted. This search for cricket clubs began by searching for evidence of intercollegiate competition, which was conducted by visiting the website of the National College Cricket Association (i.e., hereafter referred to as NCAA; a governing body currently responsible for convening an annual amateur national championship that is preceded by qualifying regional championships). Beyond searching for evidence of competitive cricket activities, further internet search engine and social media key word searches were conducted (e.g., “university cricket club” and “college cricket club”). These key word searches enabled a snowball effect whereby the published activities of college cricket clubs disclosed details of involvement by other college cricket clubs. Finally, targeted searches of specific colleges and universities with large numbers of international students were conducted. This targeting was justified by how cricket participation and fandom in the United States is dominated by the Indian diaspora – both in terms of the growing native-born Indian American population (i.e., second- and third-generation immigrants), but also foreign-born nationals who relocate stateside (see 21, 33). The term “active” was operationalized as evidence of facilitation of at least one cricket-related activity by the club across the 2024-25 academic year inclusive of summer 2024 (i.e., June 1, 2024 to March 1, 2025).

This initial data collection step, which was a precursor to the main data collection, was conducted over the month of February 2025. The outcome yielded a total of 106 active college cricket clubs. As shown in Figure 1, these active college cricket clubs were geographically dispersed but with concentrated hubs in the Boston, New York, DC, Chicago, and Los Angeles metropolitan areas. This total population was further divided into three classification categories. Specifically, 55 college cricket clubs existed within the institution’s club sport program, 42 college cricket clubs existed as registered student organizations, and nine college cricket clubs appeared to be either unaffiliated with their host institution or their status regarding governing authority was not disclosed.

Figure 1

Note. Cluster map of 106 active college cricket clubs identified by the researchers via an extensive multi-pronged search of secondary data sources.

The next data collection step involved accessing the most recent constitutions for the active college cricket clubs. These documents were sourced via the host institution’s website either through their dedicated club sport program pages or their registered student organization databases. Importantly, publicly accessible constitutions were not available for all college cricket clubs in the total population. In fact, 35 constitutions were accessed to form the sample population. Within this sample population, 22 college cricket clubs existed as registered student organizations alongside 13 within the institution’s club sport program.

With 35 constitutions accessed, the next step was extracting consistent content from each document. Organizational purpose is multi-faceted. At a basic level, purpose defines the remit and scope of business activities (18). Purpose also extends the what to the why by articulating an organization’s reason for being (14). Importantly, constitutions often vary according to the needs of each organization (8). While variance was evident within the constitutions sampled for this research, the information provided within Article II relative to organizational purpose provided the most consistent and relevant source from which to interpret the stated purpose of said clubs and student groups. Article II content within the sampled constitutions ranged anywhere from a minimum of 18 words to a maximum of 77 words.

To prepare the data for analysis, the Article II content for each of the college cricket clubs in the sample population was standardized into a series of discreet one-sentence statements. Importantly, this data preparation step did not alter the meaning of the Article II content; rather the focus was a grammatical one through the elimination of run-on sentences that included two or more independent ideas presented together without proper use of punctuation or conjunctions. In sum, data collection yielded 102 statements and 1,752 words of textual data for analysis. This process was akin to how Krippendorff (20) defines sampling versus context units in content analysis. Specifically, the Article II content are considered the sampling units (N=35), whereas the statements formed the context units (N=102).

Data Analysis

Of utmost importance with content analysis is reliability. Ultimately, “different people should code the same text in the same way” (42). The following passage outlines the decisions made by the researchers to ensure reliability.

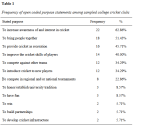

Based on the variation within the Article II content, the researchers agreed to use a multiple classification system whereby each context unit could be assigned to more than one category or recording unit (19). In the absence of an existing content analysis dictionary, the researchers also agreed to develop inferred categories. Specifically, with an emergent coding approach, categories are established following some preliminary examination of the data (35). The researchers then adhered to the steps outlined by Haney and colleagues (13) in conducting emergent coding in content analyses. First, the researchers reviewed the statements and independently formed a checklist. Second, the researchers met (virtually) to reconcile differences in the checklists. Third, the researchers agreed to use a consolidated checklist to independently apply coding. The checklist included 12 specific features of the data that communicated a reason why the clubs facilitated cricket activities on campus (i.e., open codes). Based on relationships among the specific features, the open codes were combined to create three axial codes. Figure 2 provides a summary of the coding categories – both open and axial – that emerged through the data analysis process, along with representative quotes from the textual data.

Figure 2

Note. Coding framework including 12 open and three axial codes derived from a series of consensus meetings held between the researchers.

The fourth step in the emergent coding process was to tally the frequency at which the open codes were evident in the data. This process was completed independently by the researchers using manual coding whereby each of the context units were categorized under one or more of the 12 checklist items. As per Roaché’s (32) method, a 94.83% agreement was calculated (i.e., 110 agreements and 116 total coding decisions). To reconcile these differences, the researchers met one more time and reached consensus on 114 recording units. While a third reviewer or adjudicator was not involved, the researchers resolved disagreements through open discussion whereby the researchers took notice of which codes were used by the other researcher and listened to their rationale for using a code before the disagreement was reconciled (6). The open code tallies were then aggregated using the axial codes to place each of the sample college cricket clubs into one of seven categories based on their purpose (i.e., a sort of purpose typology). The seven typologies included: 1) Performance only, 2) Participation only, 3) Promotion only, 4) Performance and Participation, 5) Performance and Promotion, 6) Participation and Promotion, and 7) Performance, Participation, and Promotion. Each college cricket needed just one open-coded purpose statement in any of the axial coding categories to be labelled as adopting that broader level purpose.

RESULTS

Purpose of Existing College Cricket Clubs

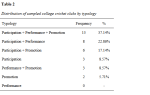

Regarding the open coding of purpose statements and as shown in Table 1, almost two thirds of the sampled college cricket clubs disclosed as their dominant remit and scope to increase awareness and interest in cricket (n=22, 62.86%). There were a further five specific purposes that emerged from the sample that were relatively common (i.e., evidence across one-third to one-half of the sampled college cricket clubs). These purposes included bringing people together (n=18, 51.43%), providing cricket as recreation (n=16, 45.71%), improving the cricket skills of players (n=14, 40.00%), competing against other teams (n=12, 34.29%), and introducing cricket to new players (n=12, 34.29%).

When aggregated to the axial coding level, the analysis (see Table 2) establishes that over one-third of the sample had a purpose that spanned across participation, performance, and promotion (n=13, 37.14%), which represents the most common typology. None of the sampled college cricket clubs had a one-dimensional purpose focusing exclusively on performance. In fact, a majority (n=30, 85.71%) of sampled college crickets had a multi-faceted purpose that extended across at least two of the three purpose categories.

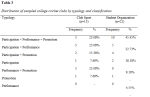

Variation in Purpose by Classification

As can be seen in Table 3, there are two typologies where some variation existed based on classification. First, a greater proportion of college cricket clubs classified as student organizations had a three-pronged purpose (n=10, 45.45%) compared to college cricket clubs classified as club sports (n=3, 23.08%). Second, more college cricket clubs classified as club sports disclosed a dual performance and promotion purpose (n=3, 23.08%) compared to college cricket clubs classified as student organizations (n=0, 0%). Beyond this variation, the distribution of college cricket clubs classified as club sports and student organizations had similar results across the remaining five typologies.

DISCUSSION

In the context of this research, readiness for varsity status would imply that a critical mass of existing college cricket clubs exists with a purpose akin to those of a varsity sport program (i.e., an emphasis on performance). The findings establish that just over two-thirds of the existing college cricket clubs sampled disclose “performance” as part of their purpose, which means their reason for being centers around supporting competitive, extramural opportunities. These findings are consistent with Czekanski and Lower’s (7) study, which identified performance or competition-based goals as one of four distinct themes emerging from collegiate sport club functions. However, when looking at the discreet purpose statements, only two of the sampled college cricket clubs included mention of athletic excellence as part of their purpose (e.g., to win a national championship). Another key omission from the purpose statements sampled, that is also evident within varsity sport, is reference to academic success. This finding is perhaps expected given how club sports and student organizations exist as extracurricular activities (i.e., optional, non-academic activities), whereas varsity sport at least purports a self-perpetuating cocurricular existence (i.e., school-sponsored programs that enhance students’ learning experiences outside the traditional classroom setting). Overall, college cricket clubs appear not to be skewed towards performance as their central purpose. Instead, many college cricket clubs disclose the intent to have a performance arm to their organization, but one that operates in tandem or combination with a multi-faceted purpose.

Promotion was another salient theme within the purpose statements sampled, which refers to how college cricket clubs’ reason for being focuses on promoting and popularizing the sport. Czekanski and Lower (7) refer to such goals as “administrative” in nature as they relate to the function of the club. Nevertheless, Czekanski and Lower (7) also highlighted goals such as increasing the number of participants as another distinct theme within club sport organizations. The results of this research establish how over two-thirds of the sampled college cricket clubs see themselves as cricket-specific community sport development agencies, which are organizations responsible for increasing participation rates in sport and building capacity to facilitate sporting opportunities (26). In fact, the scope of the “community” to which college cricket clubs bear responsibility ranged from city to region to the nation. As an example, one sampled college cricket club disclosed within their purpose the goal to “promote the sport of cricket at the university and the USA.” These are grand purposes for organizations that are traditionally under-resourced or self-financed on a pay-to-play model basis. For context, a national sport governing body like USA Lacrosse invests over $2 million a year in the sport’s development (39).

A lack of research exists that is dedicated to understanding how the classification of student-led groups impacts the purpose of such groups. This research responds to that dearth of research – albeit in the very specific context of cricket. Ultimately, this research found that students organized around a sport activity have a mostly consistent reason for being irrespective of their classification as a club sport or student organization. Perhaps this absence of distinct variation is indicative of how most recreational sport departments – the departments responsible for supervising club sports – are housed within the division of student affairs (11), which also where student organizations report. Using the University of Wisconsin-Madison as an example, both registered student organizations and sport clubs follow student organization resource and policy guides (36). In addition, both registered student organizations and sport clubs must have officers as students and consist of 75% student membership (36). Yet, the results of this research point to some subtle differences between the purpose of college cricket clubs classified as club sport organizations versus student organizations. Interestingly, two of the 13 club sport college cricket clubs sampled included no mention of performance within their purpose statement. This finding is perhaps explained by the variability in Article II language and how some club sport college cricket clubs chose to articulate their reason for being (14); rather than the remit and scope of business activities (18). In this way, competition and performance is implied, if not stated.

CONCLUSION

Irrespective of the readiness of the existing organized college cricket structures, cricket has a difficult path to achieving varsity status. Notably, and given its traditional team sport nature, cricket is unlikely to receive a federal Title IX exemption like esports (see 3). Therefore, any attempts to elevate cricket to varsity status would likely need to be through a strategic elevation of women’s cricket first. And while not within the scope specifically of this research, any cursory glance into college cricket activities will unearth an almost exclusively male dominated space. Furthermore, interest and participation in cricket among women and girls is low in the USA as the sport has “suffered from an inadequate domestic structure and a lack of investment and organizational interest in developing a more inclusive and welcoming environment” (38). So, while little promise exists in elevating college cricket to varsity status in its current form, this research does point towards a readiness for increased emphasis and investment in competitive men’s college cricket. The challenge, as stated, is the viability of an elevation to varsity status or whether the elevation occurs within the parameters of the existing club sport model.

One of the limitations of this research is the inability to secure constitutions for a greater proportion of the total population of existing college cricket clubs. One way the researchers considered accounting for this was to collate mission statements from other sources such as social media profiles and bios. However, to uphold the integrity of the content analysis and ensure the data being analyzed was comparable, a decision was made to stick exclusively to the content found within constitutions. The authors also recognize how there could be a disconnect between what college cricket clubs disclose in their constitutions versus what happens in reality; like how Chelladurai (5) differentiates between the stated and real goals of sport organizations. Future research should explore any possible differences between the actual activities of college cricket clubs versus how college cricket clubs are formalized constitutionally. Also, this research was framed from the perspective of college cricket clubs and their readiness for varsity-level sport. Therefore, future research should also look to understand the perceptions of those working within varsity sport – so intercollegiate athletic administrators – on the path forward for college cricket in the United States.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

Those entities responsible for convening intercollegiate competition – whether that be the CCL or NCCA – should, if not already, look to the purpose of individual college cricket clubs when canvasing for increased participation in intercollegiate competition. This research, if generalizable across the total population of college cricket clubs nationally, suggests few if any of these organized cricket structures consider performance as their only purpose. Ultimately, college cricket clubs are heterogenous in relation to their core activities and reason for being (i.e., many are not operating as pseudo-varsity, non-scholarship athletic programs).

This research also has relevance to USA Cricket in their continued attempts to guide the development of the sport nationally. Notably, USA Cricket recognizes that the sport has not yet found a way to integrate effectively into colleges, but had also committed to develop a plan that promotes the meaningful engagement of cricket by colleges across the nation (37). That plan appears to be the establishment of CCL, which has been developed by the National Cricket League USA but in partnership with USA Cricket (see 28). Importantly, this research suggests USA Cricket and CCL’s plan does tap into multiple priorities of existing college cricket clubs – namely through the provision of additional extramural competition, as well as the increased awareness of cricket that planned media exposure will bring.

This research also suggests that many college cricket clubs adopt a “grow the game” in addition to or instead of a “high performance” philosophy. As a result, universities and colleges may also be well-placed to support other strategic themes within USA Cricket’s Foundational Plan such as to increase participation, which again was a salient reason for being for many college cricket clubs in the sample. This purpose has potential value given how students at institutions of higher education appear more willing and likely to get involved in all kinds of organizations when compared to other settings and life stages (23). Such participation objectives could be achieved collectively through, for example, a refresh and revamp of the NIRSA/ICC Campus Cricket Program, which contributed to 40 colleges and universities offering intramural cricket to nontraditional audiences over a two-year period (16).

This research also has relevance to campus recreation professionals supporting the efforts of college cricket clubs. Given the multi-faceted role of college cricket clubs across performance, participation, and promotion dimensions, these organizations are contributing against multiple strategic priorities of higher education institutions. Given how many colleges and universities are removing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs, perhaps non-varsity college sport is an indirect means through which higher education institutions can continue to promote DEI among their student bodies. Cricket has potential as a unifier – especially for the South Asian population in North America (see 1). But, as mentioned, the results of this research suggest college cricket clubs are organized to proactively grow the game among non-traditional audiences and bring people together from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds in the process. Alternatively, non-varsity college sport is likely to boost student retention rates, as well as a potential increase in international student enrollment moving forward (i.e., a lucrative market in the face of the domestic enrollment cliff). One institution that clearly recognizes this potential is Wichita State University who worked with the local Parks and Recreation agency to construct a cricket field to help the circa 3,100 international students on campus to feel more at home (24). As such, campus recreation professionals should look to highlight the purpose and resulting outcomes of college cricket clubs when advocating for fair allocation of institutional funds to support such activities.

REFERENCES

- Al-Heeti, A. (2015, April 30). Unifying cultures through cricket. The Daily Illini. https://dailyillini.com/uncategorized/2015/04/30/unifying-cultures-through-cricket/

- American College Cricket. (2017, September 17). Welcome to American College Cricket. https://cricclubs.com/americancollegecricket/viewNews.do?newsId=1&clubId=3456

- Bauer-Wolf, J. (2023, March 3). First-of-its-kind court ruling says college esports don’t fall under Title IX. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/college-esports-dont-fall-under-title-ix/643822/

- Bourne, H. & Jenkins, M. (2013). Organizational values: A dynamic perspective. Organization Studies, 34(4), 495-514.

- Chelladurai, P. (2014). Managing organizations for sport and physical activity: A systems perspective (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Chinh, B., Zade, H., Ganji, A., & Aragon, C. (2019, May 4-9). Ways of qualitative coding: A case study of four strategies for resolving disagreements. 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland. https://faculty.washington.edu/aragon/pubs/Chinh-CHI2019.pdf

- Czekanski, W. A. & Lower, L. (2019) Collegiate sport club structure and function. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(2), 231-245.

- Dartmouth College Council on Student Organizations. (n.d.). Sample constitution. https://students.dartmouth.edu/coso/recognition/coso-recognition/writing-constitution/sample-constitution

- Elo, S. & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107-115.

- Florea, M. (2024, August 2). 7 types of US college student organization. QS Top Universities. https://www.topuniversities.com/blog/7-types-us-college-student-organization

- Franklin, D. S. (2007). Student development and learning in campus recreation: Assessing recreational sports directors’ awareness, perceived importance, application of and satisfaction with CAS standards (Doctoral dissertation, Ohio University).

- Haines, D. J. & Fortman, T. (2008). The college recreational sports learning environment. Recreational Sports Journal, 32(1), 52-61.

- Haney, W., Russell, M., Gulek, C., & Fierros, E. (1998). Drawing on education: Using student drawings to promote middle school improvement. Schools in the Middle, 7(3), 38-43.

- Harvard Business Review. (2016, April 20). The business case for purpose. https://hbr.org/resources/pdfs/comm/ey/19392HBRReportEY.pdf

- Haverford Athletics. (n.d.). Cricket history. https://www.haverfordathletics.com/sports/cricket/team_history

- Helbing, E. (2017, December 4). The NIRSA/ICC cricket program continues to make headway. NIRSA. https://nirsa.net/2017/12/04/nirsa-icc-cricket-program-update/

- Hussain, U. (2024, June 19). America’s cricket “miracle”: Integration, defiance, or immigrant’s nostalgia? First and Pen. https://firstandpen.com/americas-cricket-miracle-integration-defiance-or-immigrants-nostalgia/

- Hollensbe, E., Wookey, C., Hickey, L., George, G., & Nichols, C. V. (2014). Organizations with purpose. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1227-1234.

- Insch, G. S., Moore, J. E., & Murphy, L. D. (1997). Content analysis in leadership research: Examples, procedures, and suggestions for future use. The Leadership Quarterly, 8(1), 1-25.

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Validity in content analysis. In Mochmann, E. (Ed.), Computerstrategien für die kommunikationsanalyse (pp. 69-112). Campus.

- Kuttappan, R. (2024, June 12). T20 World Cup: Indian-origin players are dominating the US cricket team and how! The Quint. https://www.thequint.com/opinion/t20-world-cup-indian-origin-players-are-dominating-the-us-cricket-team

- Lambert, V. A. & Lambert, C. E. (2012). Qualitative descriptive research: An acceptable design. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 16(4), 255-256.

- Lifschutz, L. (2012). Club sports: Maximizing positive outcomes and minimizing risks. Recreational Sports Journal, 36(2), 104-112.

- Longi, N. (2024, July 24). WSU builds a cricket field to help international students feel at home. KMUW. https://www.kmuw.org/sports/2024-07-24/wsu-builds-a-cricket-field-to-help-international-students-feel-at-home

- March, L. (2020, October 28). Penn’s oldest sport goes back 168 years, and it’s not one you might think. The Daily Pennsylvanian. https://www.thedp.com/article/2020/10/penn-cricket-team-historical-feature

- Mori, K., Morgan, H., Parker, A., & Lindsey, I. (2024). Placing community at the heart of community sport development: introducing the community sport development framework (CSDF). Sport in Society, 28(3), 433-451.

- Nachmias, D. & Nachmias, C. (1976). Research methods in the social sciences (1st ed.). Edward Arnold.

- National Cricket League USA. (2024, December 4). Collegiate Cricket League (CCL) introduces global cricket to U.S. colleges. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/collegiate-cricket-league-ccl-introduces-global-cricket-to-us-colleges-302322587.html

- Penry, J. (n.d.). Athletics in the higher education philanthropic ecosystem. Athletic Director U. https://athleticdirectoru.com/articles/athletics-in-the-higher-education-philanthropic-ecosystem/

- Pew Research Center. (2024, August 6). Indian Americans: A survey data snapshot. https://www.pewresearch.org/2024/08/06/indian-americans-a-survey-data-snapshot/

- Prasad, B. D. (2008). Content analysis. In D. K. L. Das & V. Bhaskaran (Eds.), Research methods for social work (pp. 173-193), Rawat.

- Roaché, D. (2017). Intercoder reliability techniques: Percent agreement. In M. Allen (Ed.), The sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 752-752). Sage.

- Sinha, H. (2024, June 18). The $125bn reason America is hosting the Cricket World Cup. Business Age. https://www.businessage.com/post/the-125bn-reason-america-is-hosting-the-cricket-world-cup

- Statista. (n.d.). Cricket – United States. https://www.statista.com/outlook/amo/sports/cricket/united-states

- Stemler, S. (2000). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 7(1).

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Recreation and Wellbeing. (2019). Differences between registered student organization and sport club status. https://recwell.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1075/2019/08/RSO-vs-Sport-Club.pdf

- USA Cricket. (2020, October 15). USA Cricket launches foundational plan. https://usacricket.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/USA-Cricket-Foundational-Plan-Final.pdf

- USA Cricket. (2021). Shaping the future for women and girls in American cricket, 2021-2023. https://usacricket.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Women-and-Girls-Action-Plan-2021-2023.pdf

- USA Lacrosse. (n.d.). How you grow the game. https://www.usalacrosse.com/magazine/field-how-you-grow-game

- Ward, R. & Hux, R. (2011). Intercollegiate athletic purposes expressed in mission statements. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 5(2), 177-200.

- Warner, S., Dixon, M. A., & Chalip, L. (2012). The impact of formal versus informal sport: Mapping the differences in sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(8), 983-1003.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis. Sage.

- William & Mary Student Leadership Development (n.d.). Student organization recognition purpose and structure. https://www.wm.edu/offices/studentleadershipdevelopment/clubsandorganizations/student-org-purpose-structure/#:~:text=Recognized%20student%20organizations%20create%20opportunities,and%20fostering%20of%20shared%20interests