The soundtrack of the Age of Dinosaurs remains a mystery. The T-rex’s roars and the screams of velociraptors we see in the movies — such as the fourth installment of Jurassic World, which opened last week — are purely the invention of sound engineers seeking to shock viewers. These supposed dinosaur sounds have permeated the popular imagination, while for years scientists could do little more than speculate. Since the vocal apparatus of animals is composed of soft parts that almost never fossilize, until very recently, the sounds of dinosaurs could only be imagined based on the canals these animals had for perceiving sounds and on certain crests and ornaments on their skulls that could serve as sound chambers. But all that is changing.

The 70 million-year-old Parasaurolophus tubicen might have sounded like a ship’s horn or an Australian didgeridoo thanks to its distinctive cranial ornamentation, as shown in a scientific recreation at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. In 1995, paleontologists at the museum recovered a fossil of the hadrosaur with a massive crest nearly a meter long protruding from the back of its head.

Like a prehistoric wind instrument, inside this unique structure there were three pairs of hollow tubes running from the nose to the top of the crest, which researchers scanned in minute detail using a CT scan. After two years of work, the result was computer simulations of how the organ would resonate if air were blown through it, digitally reconstructed with the help of computer scientists. “I would describe the sound as otherworldly. It sent chills through my spine,” Tom Williamson, one of those paleontologists, recently told the BBC.

No one knows for sure what the enormous diversity of dinosaurs that existed throughout the Mesozoic sounded like. The soundscape would have been different at each of the three stages of the more than 180 million years that spanned it, but science has made some attempts. Based on the shape of the inner ears and other cranial cavities, scientists have developed theories about what this group of extinct reptiles might have sounded like.

If the purpose was to communicate and warn of danger, the dinosaurs’ hearing would have had to be subordinate to that function; their small auditory structures would have perceived low frequencies, just as modern crocodiles do. Animals are supposed to perceive the types of sounds they themselves can produce. No screams or roars. It’s more likely that most large dinosaurs emitted long-wavelength, low sounds capable of traveling long distances and shaking the earth. A low, amplified hiss, something like a beastly ancestor of the Italian opera singer Cesare Siepi, considered one of the best lyric basses of the 20th century.

However, the imagination must stretch in another direction, one that lessens the terror of the sounds of some of these prehistoric beasts. Until recently, it was believed that high-pitched calls and high shortwave frequencies were reserved for birds, but in 2023, a discovery emerged from the sands of the Gobi Desert (Mongolia) that changed everything.

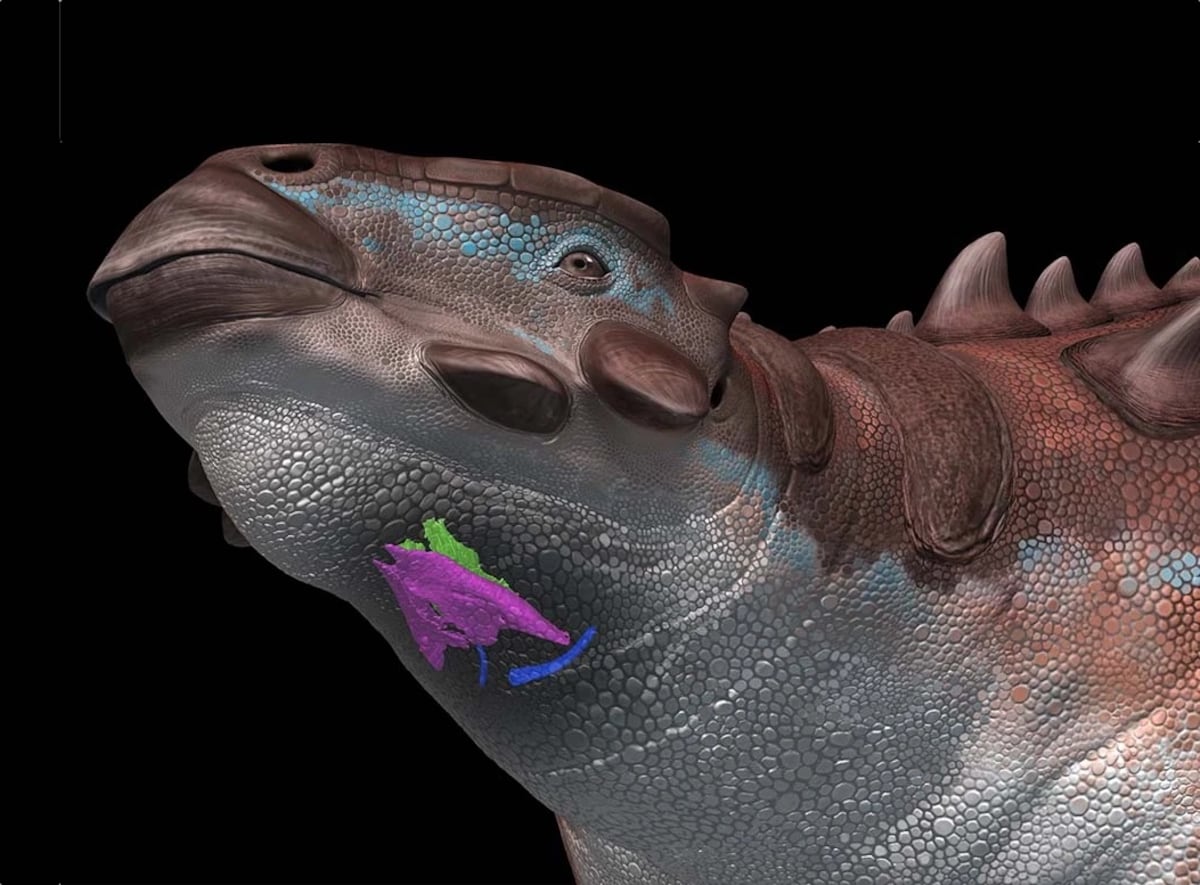

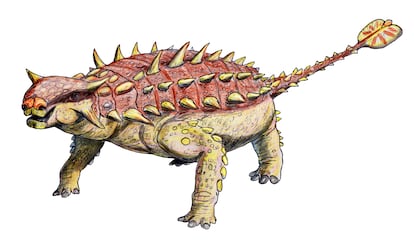

It was a fossilized larynx of the ankylosaur Pinacosaurus grangeri — a three-ton, quadrupedal, herbivorous armored vehicle almost two meters in height and about five meters in length — which suggested that birdsong could have also come from wingless animals. “This is the first discovery of a vocal organ from non-avian dinosaurs in the long history of research on them. Interestingly, the larynx of Pinacosaurus is similar to that of modern birds, so it probably used it to modify the sound like birds, rather than the vocalization typical of reptiles. Therefore, we can say that Pinacosaurus basically sounded similar to birds,” says in an email the Japanese paleontologist Junki Yoshida, first author of the discovery, which was published in the journal Nature.

The larynx is made of cartilage, a type of soft tissue that is easily disintegrated by microorganisms and environmental erosion, so its natural preservation over millions of years is exceptional. Therefore, paleontology has turned to other resources to try to reconstruct something as intangible as sound. “Dinosaur sound communication had been studied only through the inner ear of the fossil skull, but not through the vocal organ itself,” explains Yoshida, openly proud of his work. “Therefore, my discovery of the larynx represents a completely new and more direct approach to studying dinosaur sound communication.”

Dawn with the song of a dinosaur

On the other side of sound — and the world — the Argentine paleontologist Ariana Paulina Carabajal, an expert in sensory biology at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), is working on cranial structures to elucidate how these extinct animals saw, heard, and moved to do what all living beings do: survive each day. “What do animals use sound for? Basically, to communicate with each other and to warn of danger, but very little is known about the emission side.”

The conclusions derived from the larynx of Pinacosaurus coincide with those drawn by Paulina Carabajal in Canada, Mongolia and Turkey, when studying a part of the inner ear of dinosaurs from the same family. “I studied one of the two ankylosaurs in which the lagena — a fundamental structure for hearing — was preserved, and when I reconstructed them, they were among the largest I’d found so far. Very long, much longer than in other dinosaurs.”

She continues: “In general, their lagenas are the same size as those of a modern crocodile; they don’t change much, but ankylosaurs have wider lagenas. So, we think they would have slightly increased their range of sound perception. Always at low frequencies because all dinosaurs tended to hear low frequencies. Now, in conjunction with the Gobi discovery, it makes sense. We understand that for some reason they heard a little differently than other dinosaurs. They had some specialization for vocalization. It’s interesting because it changes the interpretation of the entire group of ankylosaurs and opens the possibility of asking: what other dinosaurs could have had a similar development?”

It’s tempting to get excited about the implications of the discovery. Taking a bit of a risk, the scientist believes that, since they were desirable prey for large carnivores, it’s not unreasonable to think that these animals were capable of producing high-pitched sounds imperceptible to their predators. But she acknowledges that reality isn’t always as linear as that reasoning, and therefore, there are other aspects to consider.

Paleontologist Fedrico Agnolín, a researcher at CONICET and the Azara Foundation, worked 10 years ago on another discovery linked to prehistoric sound: an exceptionally preserved syrinx from a species of duck extinct 70 million years ago was the first direct evidence of the typical vocal apparatus of birds that coexisted with the last dinosaurs. In light of Yoshida’s discovery, he proposes a bold reconstruction. “That dinosaur’s vocal repertoire is somewhere between that of songbirds and parrots. It’s not that we’re thinking it sounded like an eagle, no. Maybe it was like a thrush that got up in the morning and started singing.”

For him, we must give free rein to our imagination. “The problem is that we have a whole wealth of previous research that we can’t get out of our heads. So, we keep imagining a Tyrannosaurus rex as a gigantic reptile, even though its relatives, whose fossils have preserved their skin, show that they were covered in protofeathers, something similar to hair. The whole body is covered in hair, let’s suppose, but we’re still unable to imagine a T. rex like that.”

More cautiously, Paulina Carabajal sets limits on creativity. “What shouldn’t be interpreted directly from Yoshida’s work is that when he emitted sounds like a bird, he had a song. It wouldn’t be like the beautiful songs birds make, but rather a rattling sound related to the way air passed through the larynx.”

This is a different instrument from that of birds, which, on the other hand, have a syrinx, a unique organ that allows them to produce those songs so appreciated by humans. “Reptiles have folds of tissue that protrude — move — into the space where the air comes out, and when they move, they generate sounds, hisses, but most reptiles don’t vocalize. Making a sound is one thing, and vocalization itself is another.” That’s why the case of the Pinacosaurus from the Gobi Desert is so surprising. Its discoverers emphasize that it and its mates could have vocalized.

The larynx of this ankylosaur is composed of two parts like that of any reptile, but with the peculiarity that between these two pieces there was mobility, which would have allowed it to control the air that entered and exited, producing sounds similar to those of some birds.

Re-evaluating many fossils

The tongue of reptiles is not mobile like that of mammals. Since it is attached to the lower part of the jaw, its movement is very limited, and only the tip remains free, preventing it from manipulating food. What is interesting about Pinacosaurus, according to Paulina Carabajal, is that “very large hyoid cartilages that support the tongue — essential for swallowing, breathing, and producing sounds — were also found. Therefore, the authors propose that this tongue was much more mobile than in other dinosaurs, perhaps allowing it to manipulate food a little when grabbing it.”

For Agnolín, surprises could emerge in specific cases. “We have to reevaluate many remains. Dinosaurs are found with some neck pieces whose exact nature is unknown. We have to see if they are syrinxes or similar structures.” Erosive factors, above all, limit certainties. “The syrinx is composed of several ossified cartilages that wrap around each other and form a kind of small drum. When the animal dies, this falls off, falls apart, and rots. So, if you find a small piece of a syrinx drum, which must be 2 millimeters in size, you wouldn’t recognize it,” the Argentine scientist laments.

Studies like his own and that of Pinacosaurus, however, encourage us to review the deposits in search of those fragments that were not identified at the time to assess the possibility that they might be sound tracks. This is something he has already done, and he regrets not having found any matches. Agnolin suspects that in many cases, human bias will also have to be overcome. “Perhaps there are some researchers who deny that this is a syrinx and will talk about other structures. All of this takes time and is part of the scientific debate, which is eternal.”

The consensus among paleontologists is that, with these insights and ongoing technological advances, solving the mystery of the dinosaurs’ sounds is closer than ever. Reconstructing the soundtrack of the Mesozoic is only a matter of time.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition