As nearly one in six couples experience fertility issues, in-vitro fertilization (IVF) is an increasingly common form of reproductive technology. However, there are still many unanswered scientific questions about the basic biology of embryos, including the factors determining their viability, that, if resolved, could ultimately improve IVF’s success rate.

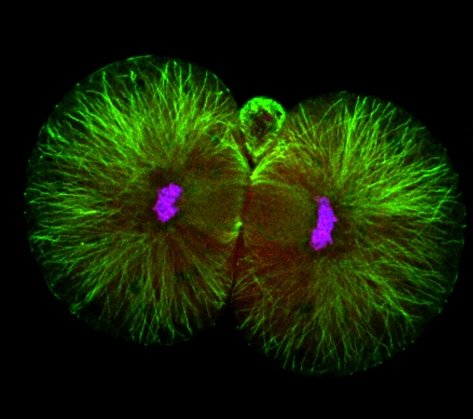

A new study from Caltech examines mouse embryos when they are composed of just two cells, right after undergoing their very first cellular division. This research is the first to show that these two cells differ significantly—with each having distinct levels of certain proteins. Importantly, the research reveals that the cell that retains the site of sperm entry after division will ultimately make up the majority of the developing body, while the other largely contributes to the placenta. While the studies were done in mouse models, they provide critical direction for understanding how human embryos develop. Indeed, the researchers also assessed human embryos immediately after their first cellular division and found that these two cells are likewise profoundly different.

The research was conducted primarily in the laboratory of Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, Bren Professor of Biology and Biological Engineering, and is described in a study appearing in the journal Cell on December 3.

After a sperm cell fertilizes an egg cell, the newly formed embryo begins to divide and multiply, ultimately becoming the trillions of cells that make up an adult human body over its lifetime. Every cell has a specialized job: immune cells patrol for and destroy invaders, neurons send electrical signals, and skin cells protect from the elements, just to name a few.

It was previously assumed that all of the cells of a developing embryo are identical, at least prior to the stage when the embryo consists of 16 or more cells. But the new study shows that differences, or asymmetries, exist even in both cells of a two-cell-stage embryo. These differences enable the specialization of the cells—in this case, leading to the formation of the body and the placenta. At this stage, the cells of the embryo are called blastomeres.

The team found around 300 proteins that are distributed differently between the two blastomeres: some overproduced in one and deficient in another, and vice versa. All of these proteins are important for orchestrating the processes that build and degrade other proteins, as the complement of proteins supplied by the mother declines and is replaced by those produced by the embryo.

The location of sperm entry into the cell seems to be a key factor determining which blastomere will play each role. Developmental biologists have long believed that mammalian sperm simply provides genetic material, but this new study indicates that the sperm’s entry point sends important signals to the dividing embryo. The mechanism through which this happens is still unclear; for example, the sperm could be contributing particular cellular structures (organelles), or regulatory RNA, or have a mechanical input. Future studies will focus on understanding this mechanism.

To make these discoveries, the Zernicka-Goetz lab collaborated with two laboratories with expertise in proteomics (the study of protein populations): the Caltech lab of Tsui-Fen Chou, Research Professor of Biology and Biological Engineering; and of Nicolai Slavov at Northeastern University.

A paper describing the study is titled “Fertilization triggers early proteomic symmetry breaking in mammalian embryos.” The lead authors are Lisa K. Iwamoto-Stohl of the University of Cambridge and Caltech, and Aleksandra A. Petelski of Northeastern University and the Parallel Squared Technology Institute in Massachussetts. In addition to Zernicka-Goetz and Chou, other Caltech co-authors are staff scientist Baiyi Quan; Shoma Nakagawa, director of the Stem Cell and Embryo Engineering Center; graduate students Breanna McMahon and Ting-Yu Wang; and postdoctoral scholar Sergi Junyent. Additional co-authors are Maciej Meglicki, Audrey Fu, Bailey A. T. Weatherbee, Antonia Weberling, and Carlos W. Gantner of the University of Cambridge; Saad Khan, Harrison Specht, Gray Huffman, and Jason Derks of Northeastern University; and Rachel S. Mandelbaum, Richard J. Paulson, and Lisa Lam of USC. Funding was provided by the Wellcome Trust, the Open Philanthropy Grant, a Distinguished Scientist NOMIS award, the National Institutes of Health, the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group, and the Beckman Institute at Caltech. Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz is an affiliated faculty member with the Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute for Neuroscience at Caltech.