BBC News in San Diego, California

BBC

BBCAs a journalist in Afghanistan, Abdul says he helped promote American values like democracy and freedom. That work, he said, resulted in him being tortured by the Taliban after the US withdrew from the country in 2021.

Now he’s in California applying for political asylum, amid the looming threat of deportation.

“We trusted those values,” he said. “We came here for safety, and we don’t have it, unfortunately.”

But when Abdul walked into a San Diego court to plead his case, he wasn’t alone.

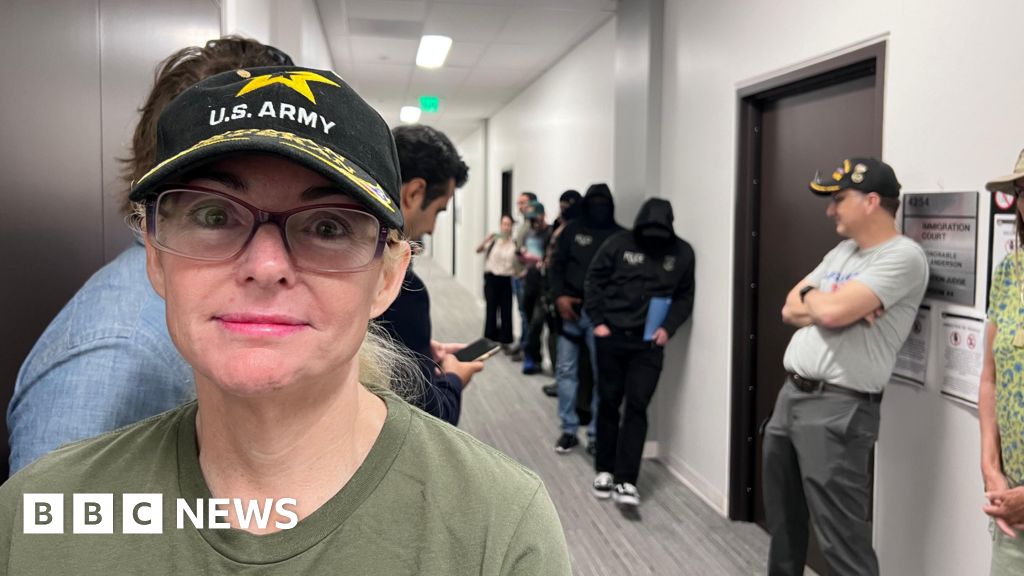

Ten veterans showed up for his hearing – unarmed, but dressed in hats and shirts to signify their military credentials as a “show of force”, said Shawn VanDiver, a US Navy vet who founded ‘Battle Buddies’ to support Afghan refugees facing deportation.

“Masked agents of the federal government are snatching up our friends, people who took life in our name and have done nothing wrong,” he said.

Approximately 200,000 Afghans relocated to the US after Kabul fell to the Taliban in August 2021, as the US left the country in chaos after two decades fighting the war on terror.

Many say they quickly felt embraced by Americans, who recognised the sacrifices they had made to help the US military and fight for human rights.

But since the Trump administration has terminated many of the programmes which protected them from deportation, Afghans now fear they will be deported and returned to their home country, which is now controlled by the Taliban.

Mr VanDiver, who also founded #AfghanEvac in 2021 to help allies escape the Taliban when the US withdrew, said US military veterans owe it to their wartime allies to try and protect them from being swept up in President Trump’s immigration raids.

“This is wrong.”

The Battle Buddies say they have a moral and legal obligation to stand and support Afghans. They now have more than 900 veteran volunteers across the country.

Many of the federal agents working for ICE and the Department of Homeland Security are veterans themselves, he said, and the Battle Buddies think their presence alone might help deter agents from detaining a wartime ally.

“Remember, don’t fight ICE,” Mr VanDiver told his fellow Battle Buddies outside court before Abdul’s hearing, referring to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known as ICE.

“If somebody does fight ICE, capture it on video. Those are the two rules.”

As Abdul and his lawyer went into court, the veterans stood in the corridor outside in a quiet and tense faceoff with half a dozen masked federal agents. It was the same hallway where an Afghan man, Sayed Naser, a translator who says he worked for the US military, was detained 12 June.

“This individual was an important part of our Company commitment to provide the best possible service for our clients, who were the United States Military in Afghanistan,” says one employment document submitted as part of Naser’s asylum application and reviewed by the BBC’s news partner in the US, CBS News.

“I have all the documents,” Mr Naser told the agents as he was handcuffed and taken away, which a bystander captured on video. “I worked with the US military. Just tell them.”

Mr Naser has been in detention since that day, fighting for political asylum from behind bars.

Department of Homeland Security Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin told the BBC that there is nothing in his immigration records “indicating that he assisted the US government in any capacity”.

Whichever way Mr Naser’s case is decided, his detention is what inspired veterans to form the Battle Buddies. They say abandoning their wartime allies will hurt US national security because the US will struggle to recruit allies in the future.

“It’s short sighted to think we can do this and not lose our credibility,” said Monique Labarre, a US Army veteran who showed up for Abdul’s hearing. “These people are vetted. They put themselves at substantial risk by supporting the US government.”

EPA

EPAPresident Trump has repeatedly blamed President Biden for a “disgraceful” and “humiliating” retreat from the country.

But the US’s withdrawal from Afghanistan was initially brokered by President Trump during his first term.

In their wake, American troops left behind a power vacuum that was swiftly and easily filled by the Taliban, who took control of the capital city, Kabul, in August 2021. Afghans, many who worked with the US military and NGOs, frantically swarmed the airport, desperate to get on flights along with thousands of US citizens.

Over the ensuing years, almost 200,000 Afghans would relocate to the US – some under special programmes designed for those most at risk of Taliban retribution.

The Trump administration has since ended this programme, called Operation Enduring Welcome. It also ended the temporary protections which shielded some Afghans, as well as asylum seekers from several other countries, from deportation because of security concerns back home.

“Afghanistan has had an improved security situation, and its stabilising economy no longer prevent them from returning to their home country,” Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said in a statement about terminating Temporary Protected Status for Afghans.

She added that some Afghans brought in under these programmes “have been under investigation for fraud and threatening our public safety and national security”.

Afghans in the United States scoff at the suggestion that they’d be safe going back, saying their lives would be in danger.

“I couldn’t work,” said Sofia, an Afghan woman living in Virginia. “My daughters couldn’t go to school.”

With the removal of temporary protected status, the Trump administration could deport people back to Afghanistan. Although that is so far rare, some Afghans have already begun to be deported to third countries, including Panama and Costa Rica.

Sofia and other members of her family were among the thousands of Afghans who received emails in April from the Department of Homeland Security saying: “It is time for you to leave the United States.”

The email, which was sent to people with a variety of different kinds of visas, said their parole would expire in 7 days.

Sofia panicked. Where would she go? She did not leave the United States, and her asylum case is still pending. But the letter sent shockwaves of fear throughout the Afghan community.

When asked about protecting Afghan wartime allies on 30 July, President Trump said: “We know the good ones and we know the ones that maybe aren’t so good, you know some came over that aren’t so good. And we’re going to take care of those people – the ones that did a job.”

Advocates have urged the Trump administration to restore temporary protected status for Afghans, saying women and children could face particular harm under the Taliban-led government.

Advocates are hopeful that Naser will soon be released. They say he passed a “credible fear” screening while in detention, which can allow him to pursue political asylum because he fears persecution or torture if returned to Afghanistan.

The Battle Buddies say they plan to keep showing up for wartime allies at court. It’s not clear if their presence made a difference at Abdul’s hearing – but he wasn’t detained and is now a step closer to the political asylum he says he was promised.

“It’s a relief,” he said outside court while thanking the US veterans for standing with him. But he said he still fears being detained by ICE, and he worries that the US values he believed in, and was tortured for, might be eroded.

“In Afghanistan, we were scared of the Taliban,” he said. “We have the same feeling here from ICE detention.”