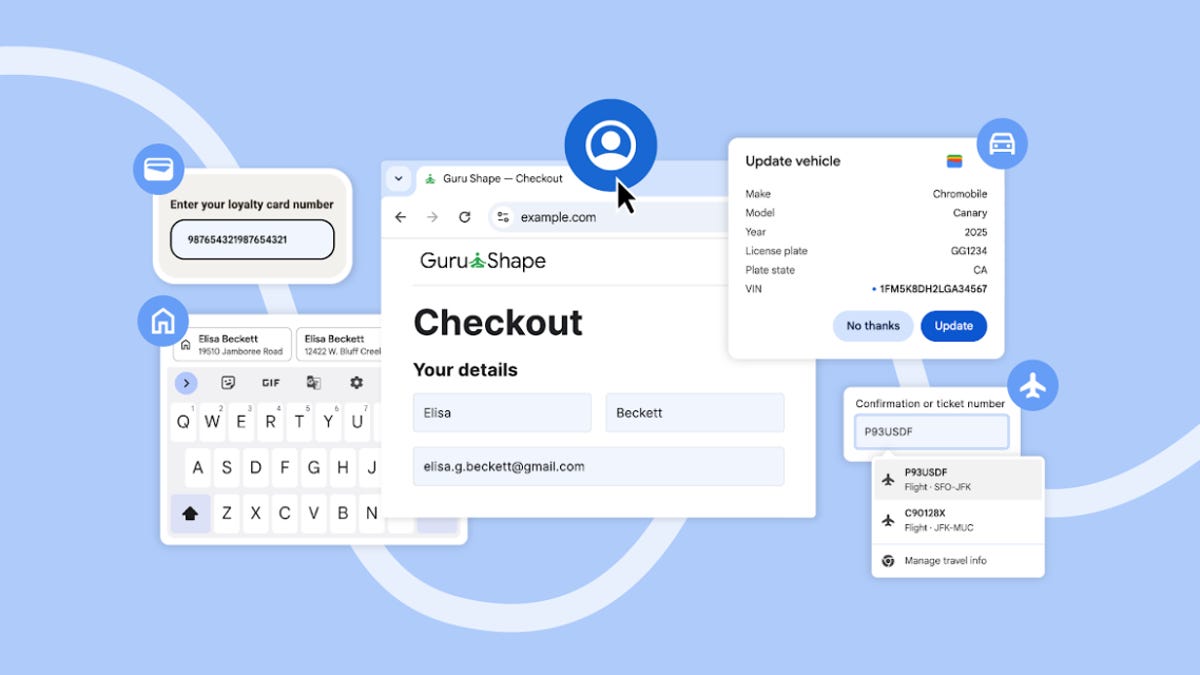

Google is expanding its autofill features for Chrome browsers to include more details such as loyalty card numbers from your Google Wallet, travel details and your work address.

Don’t miss any of our unbiased tech content and lab-based reviews.

Google is expanding its autofill features for Chrome browsers to include more details such as loyalty card numbers from your Google Wallet, travel details and your work address.

Don’t miss any of our unbiased tech content and lab-based reviews.