Since the turn of the century, the growing impact of Climate Change has inspired plans for space settlement. For many, establishing habitats in space and on other celestial bodies is a matter of survival, of creating “backup locations” for humanity so no single cataclysmic fate could lead to our extinction. This presents many challenges since spaceflight presents numerous hazards, including radiation exposure and the physiological and psychological effects of time spent in microgravity. Ongoing research aboard the International Space Station (ISS) has shown that these effects include muscle atrophy, bone density loss, and genetic changes.

There are also many unanswered questions about how time spent in space could affect our ability to produce healthy offspring. How this will affect egg and sperm precursor cells (“germ cells”) is particularly important since any irreversible damage they experience will be passed on to offspring. Using stem cells from mice, researchers from Kyoto University tested the potential damage spaceflight has on germ cells and offspring produced by them. Fortunately, their experiment resulted in a healthy litter of mice, which is good news for future generations of humans and animals that may be born in space.

The research, which was published in Stem Cell Reports, was led by Mito Kanatsu-Shinohara, an Assistant Professor of Molecular Genetics at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Medicine and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). He was joined by fellow researchers from Kyoto University, including the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application, and the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Biology (WPI-ASHIBi), and researchers from the RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project (AIP), the Japan Space Forum, and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

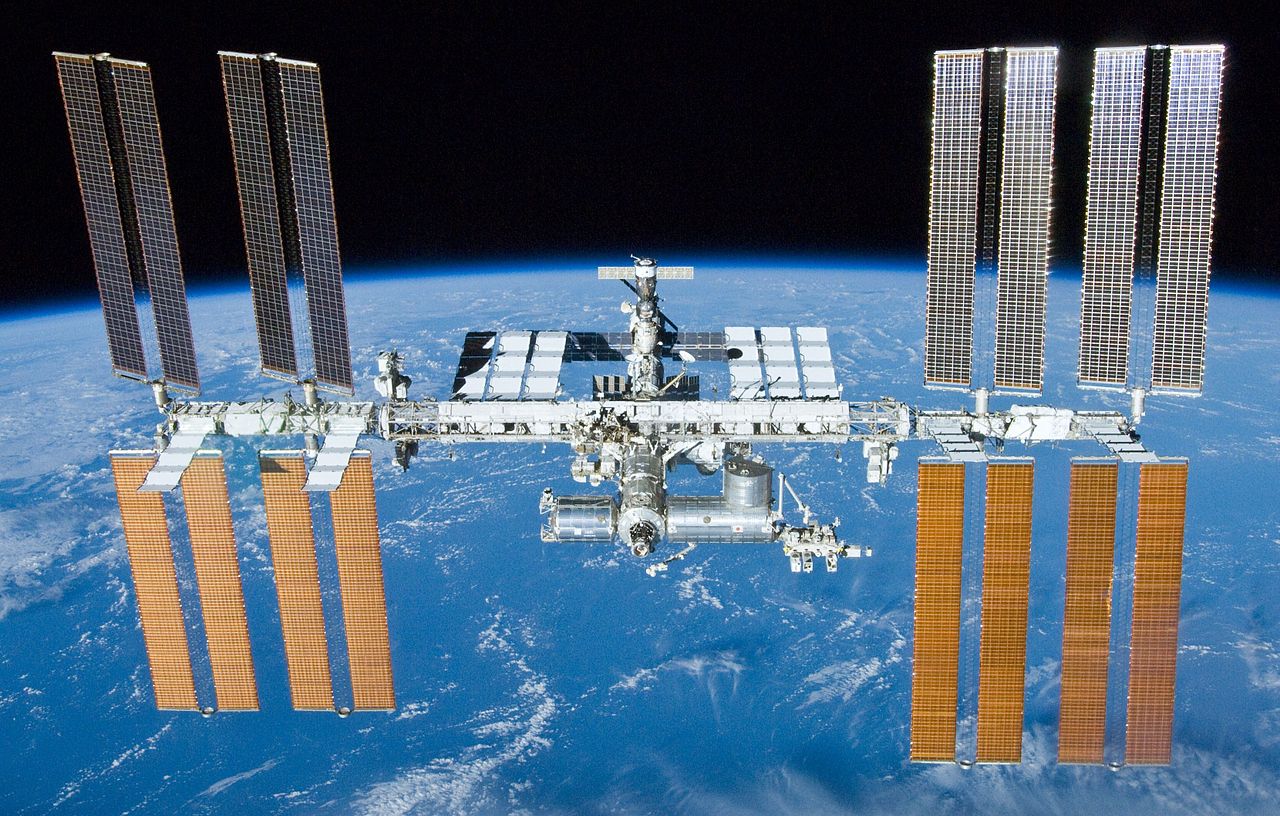

Stem cells from mice cryopreserved on the International Space Station for six months have produced healthy offspring. Credit: KyotoU/Shinohara lab

Previous studies involving embryonic stem cells showed that spaceflight resulted in abnormalities, but the exact cause has remained unknown. This inspired Prof. Kanatsu-Shinohara and his colleagues to conduct their study, which consisted of sending cryogenic samples of stem cells to the ISS, where they were stored for six months. Mice spermatozoa stem cells were specifically selected because they have a shorter reproductive life span than humans. These cells were then returned to Kyoto University and examined, which revealed no apparent abnormalities.

Three to four months later, the samples were thawed and injected into the testicles of male mice that were mated with females to produce offspring. When the team examined these “space mice” babies, they were found to be healthy and exhibited normal gene expression. The team originally predicted that spaceflight would be more harmful than cryopreservation due to the stem cells’ sensitivity to radiation. However, the results indicated that while the hydrogen peroxide used in the cryopreservation process killed off some of the cells, the effects of spaceflight proved minimal.

Moreover, the team found that cryopreserved germ cells maintain fertility for at least six months. Said Professor Kanatsu-Shinohara:

It is important to examine how long we can store germ cells in the ISS to better understand the limits of storage for future human spaceflight. We still have some spermatogonial stem cells frozen on the ISS, so we will continue to conduct further analysis.

These findings affirm previous research showing that stem cells from many species can be cryopreserved for extended periods and still produce sperm. As a result, these findings are helping to lay the groundwork for stem cell preservation during long-duration space missions. However, additional research is needed to address possible long-term health issues, which cannot be ruled out until the lifespan and fertility of these mice (as well as their progeny) are analyzed. Similarly, the research is a long way from testing the effects of spaceflight on human fertility and reproduction.

Further Reading: University of Tokyo, Stem Cell Reports