In August 2025, a consortium led by Mitsubishi Corporation announced its withdrawal from three offshore wind projects in Japan. The decision raised concerns about the viability of the country’s offshore wind sector, long viewed as a cornerstone of its renewable energy expansion. The stated cause — surging construction costs linked to inflation — is not unique to Mitsubishi; developers across Europe and elsewhere face the same challenge.

Yet it would be premature to conclude that offshore wind development in Japan has reached a dead end. Although developers are grappling with structural barriers, the government has begun reassessing its auction framework and implementing reforms that could make the next bidding round more attractive.

Japan’s wind energy plans

Japan’s 7th Strategic Energy Plan aims to increase the share of renewable energy in power generation from approximately 20% to 40%–50% by fiscal year (FY) 2040. Within this target, wind power is expected to rise from approximately 1% to between 4% and 8%, with offshore wind positioned as the centerpiece of this expansion. Japan added more offshore wind capacity in 2024 than ever before, albeit from a modest base, reaching 253.4 megawatts (MW) of operational offshore wind capacity. Meanwhile, onshore wind capacity stood at 5,330MW at the end of that year.

In 2020, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) published its “Vision for Offshore Wind Power Industry,” aiming for 10 gigawatts (GW) of total wind capacity by 2030. METI began drafting a second version of the plan in March 2025. Meanwhile, the Japan Wind Power Association has outlined a longer-term vision to build 140GW of wind capacity by 2050, comprising 40GW onshore, 40GW fixed offshore, and 60GW floating offshore capacity.

Recent political developments in Japan are likely to affect the trajectory of its energy policy. The newly elected prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, has been a strong advocate for nuclear energy and has highlighted the risks of relying on foreign suppliers for conventional solar panels. While she has shown less resistance to offshore wind, she has emphasized a goal of achieving 100% energy self-sufficiency. Under her administration, Japan’s decarbonization strategy is expected to place greater emphasis on energy security and industrial competitiveness.

Mitsubishi’s winning bids and subsequent withdrawal

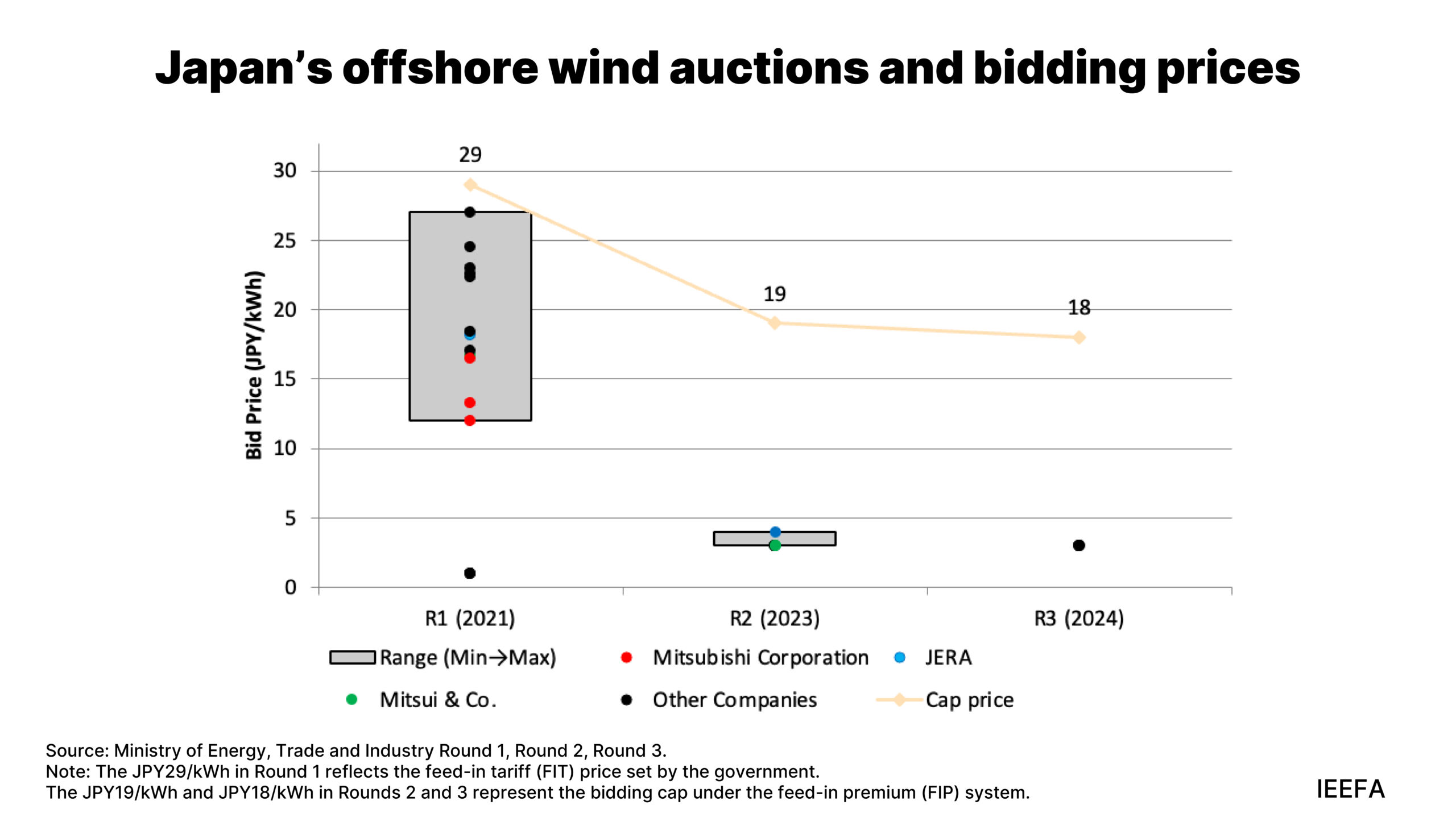

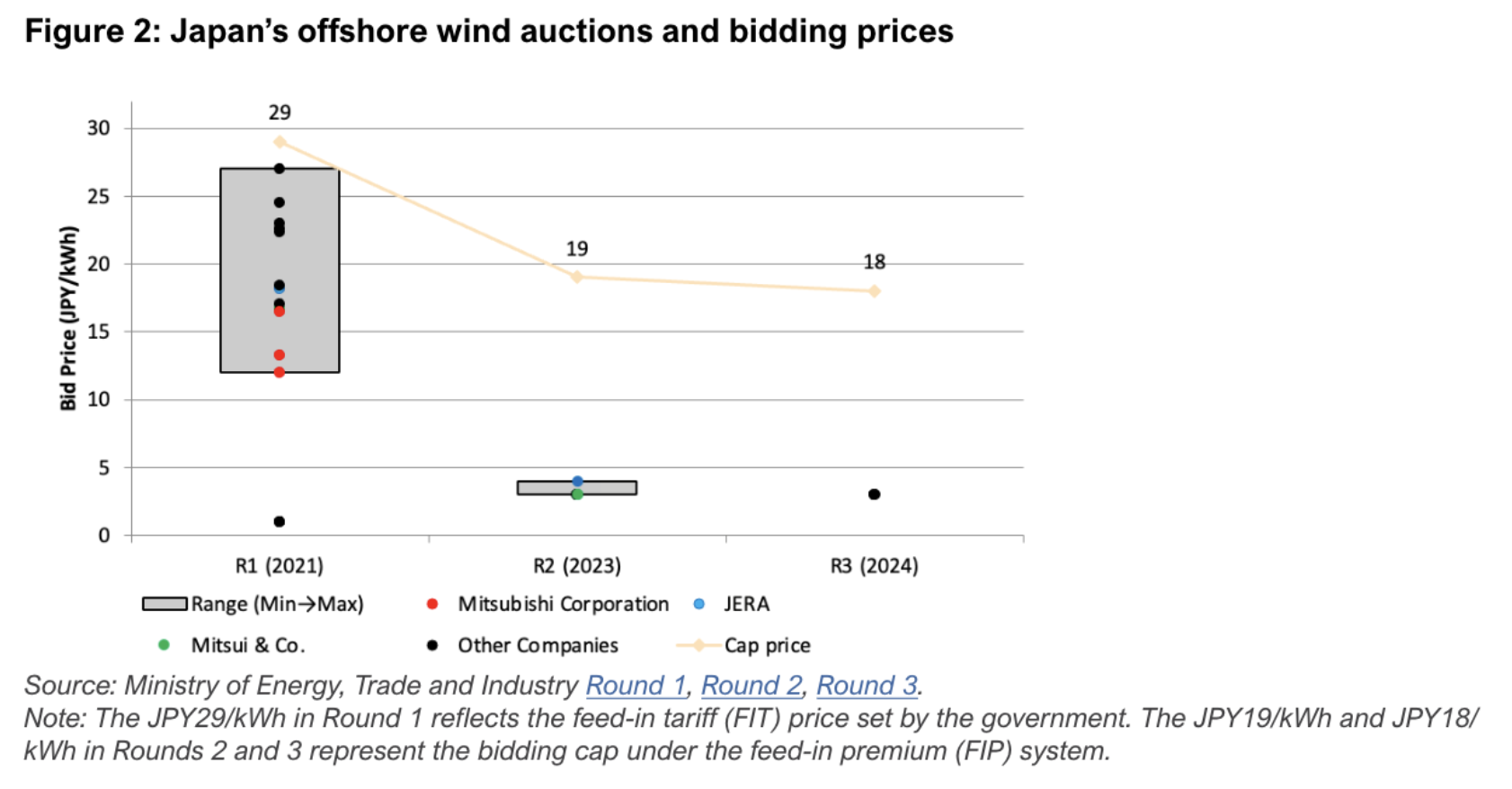

Mitsubishi’s withdrawal from three offshore wind projects reflects both company-specific missteps and broader structural issues in Japan’s offshore wind market. In 2021, Japan held its first offshore wind auction for three projects with a combined capacity of 1.7GW. Under the feed-in tariff (FIT) scheme, companies would compete for projects by submitting low-cost bids but would ultimately win contracts set at higher, predetermined fixed rates. The process enabled price discovery while also enhancing financial security for project backers.

In the first round, a Mitsubishi-led consortium won all three projects with a bidding price between JPY11.99 and JPY16.49 per kilowatt-hour (kWh), or USD10.85 cents per kilowatt-hour (¢/kWh) and USD14.8¢/kWh. This was far lower than the JPY29/kWh (USD26.1¢/kWh) ceiling price set by the government and the JPY17–JPY24.5/kWh (USD15.3¢/kWh to USD22.0¢/kWh) range from other bidders. Mitsubishi’s bid range was closer to that seen in more mature, established European markets than in an inaugural auction. These bids appeared competitive but left little buffer for cost inflation.

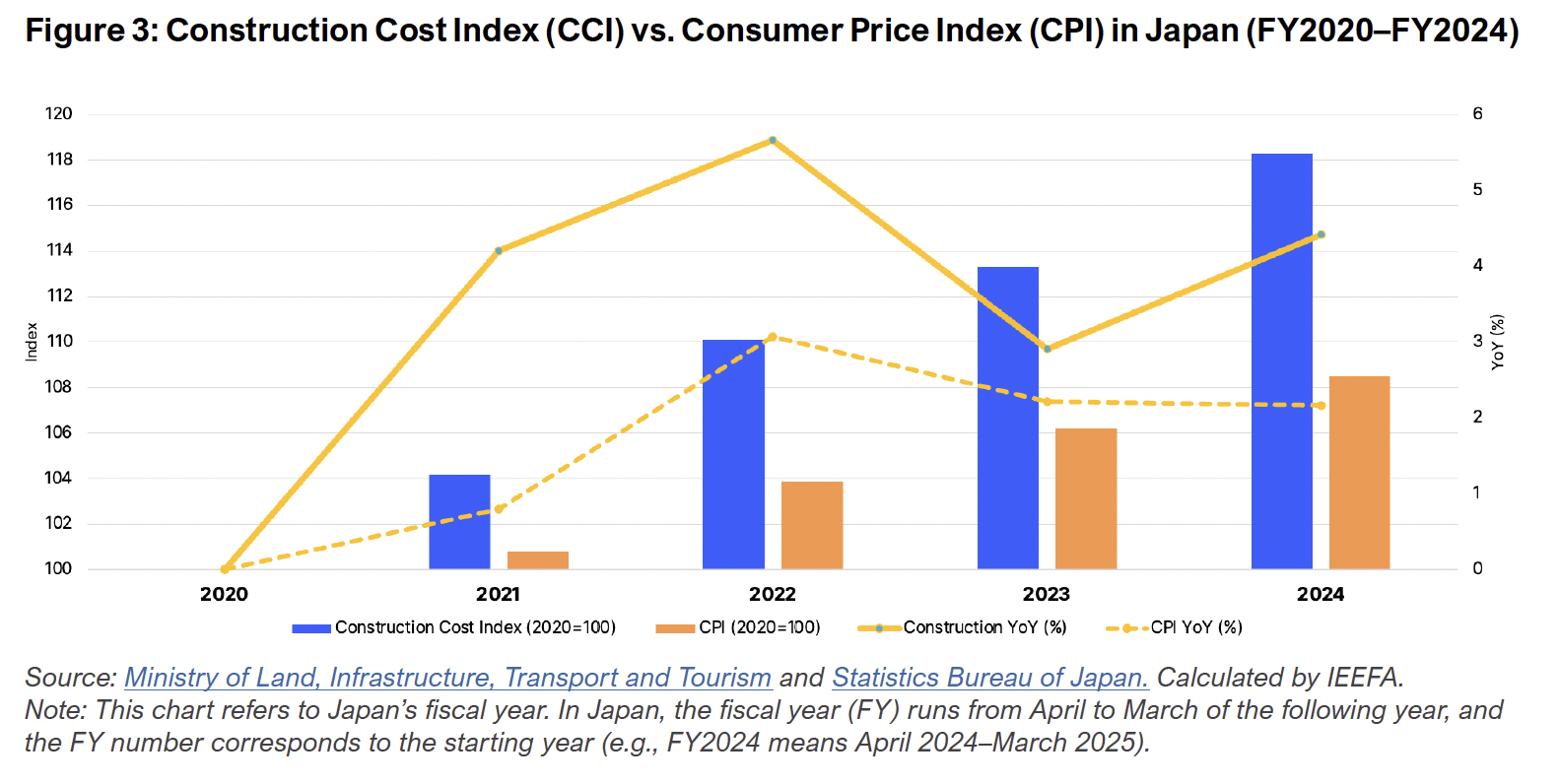

In the years following the auction, Mitsubishi’s project costs more than doubled, with total investment ballooning above JPY1 trillion (USD6.4 billion). The company announced a JPY52.2 billion (USD0.3 billion) impairment on the three offshore wind projects, exacerbated by inflation, global supply chain disruptions, yen depreciation, and rising turbine costs. In Japan, average construction costs for offshore wind projects were 20% higher in FY2024 than in FY2020, compared to an 8.5% increase in the cost of consumer goods. This is broadly consistent with trends in Europe, where capital costs increased by 18% between 2019 and 2024.

Factors constraining Japan’s offshore wind sector

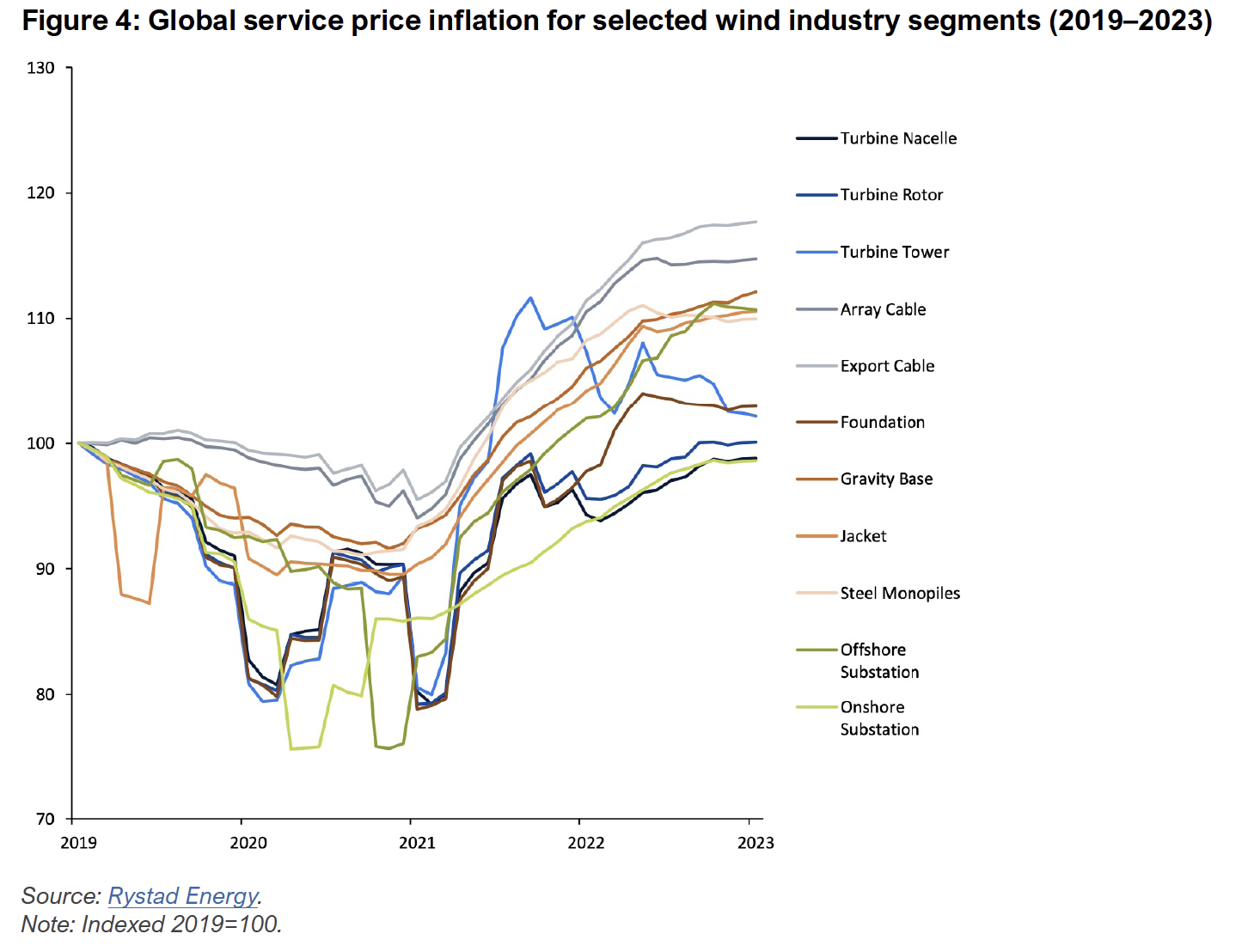

Across the wind energy industry, all major segments — turbines, cables, foundations, and substations — have been affected by inflation, driven by rising raw material and energy prices, as well as persistently high shipping rates. Global equipment and materials prices have surged since 2022, particularly for turbines, subsea cables, monopiles, and substations, driving engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) costs higher. For example, wind turbines have typically accounted for 30% of the capital expenditure (capex) required for Japanese fixed offshore wind projects in FY2025. However, turbine costs reportedly increased by 10%–15% between 2021 and 2023.

Monopile foundation costs, which typically account for approximately 8% of capex for Japanese wind projects, have been almost entirely sourced from Europe. European steel prices, the main cost driver for turbines and monopiles, surged by around 200% between late 2020 and mid-2022. Although global steel prices have since fallen to near-2019 levels, the decline in turbine costs has been slow. Shipping and installation expenses have also increased due to post-COVID supply chain bottlenecks. Transporting monopiles from Europe can cost around JPY300 million (USD1.9 million), underscoring Japan’s reliance on imports — a challenge that extends across its offshore wind supply chain.

By 2040, Japan aims to achieve over 65% local content across its entire offshore wind supply chain. Currently, however, the country lacks a domestic supplier for offshore wind turbines. Toshiba plans to establish a nacelle assembly line at its Yokohama plant in partnership with General Electric (GE), but production has not started yet. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Hitachi also previously pursued wind turbine manufacturing, but were unable to establish a sustained, large-scale domestic supply foundation. As a result, Japan’s offshore wind projects continue to rely heavily on imported turbines. Nevertheless, there are opportunities to substantially increase the proportion of wind farm costs sourced domestically, even in the absence of a full turbine manufacturing base.

Importantly, turbines now account for less than 30% of total offshore wind capex in Japan. The remaining 70% consists of balance-of-plant components — foundations, towers, cables, transmission systems, installation vessels, port upgrades, and operations — many of which align closely with Japan’s existing industrial strengths. The country already hosts globally competitive firms in specialty steel production, heavy fabrication, electrical equipment, shipbuilding, and marine logistics.

Therefore, what is lacking is not industrial capability but the effective mobilization of that capability. Irregular auction schedules and an unpredictable long-term project pipeline have prevented domestic industries from scaling or repositioning to meet offshore wind demand, reinforcing reliance on imported equipment, even when domestic alternatives exist.

Japan already forges the specialty steels used in offshore wind foundations and turbine towers. Despite this, developers continue to import these components from Europe. Hitachi, Toshiba, and Mitsubishi manufacture a large proportion of the transmission system components needed for both offshore and onshore portions of wind farm interconnections. The country also has a world-class shipbuilding industry, capable of fabricating vessels of all sizes and specialties, which is a critical requirement for offshore wind farms. These ships need crews, port facilities, and maintenance services, reinforcing the potential for domestic economic spillovers if offshore wind supply chains are localized.

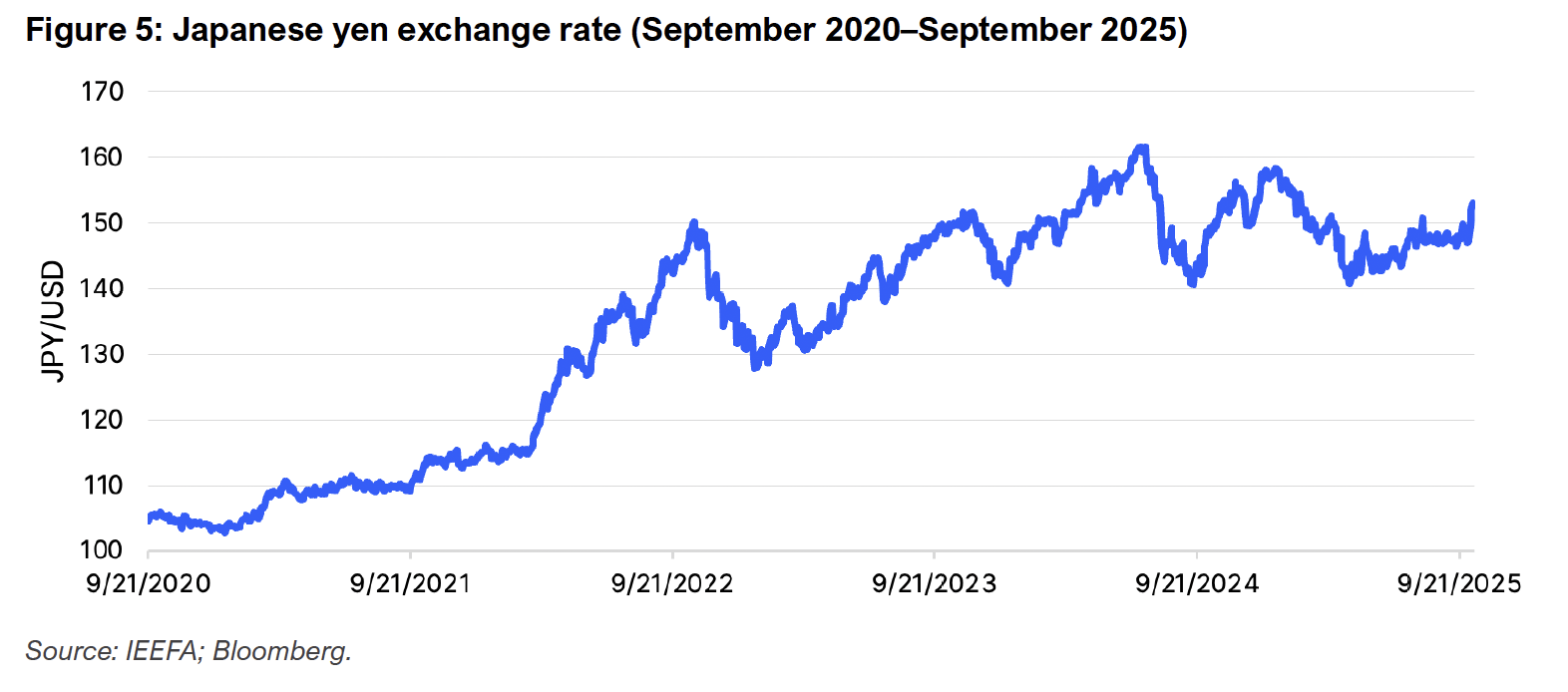

Along with higher component costs, the weak yen and rising interest rates have increased import and capital financing costs. Since 2021, the yen has significantly weakened. On an annual-average basis, the exchange rate increased from 109.78 JPY/USD in 2021 to 151.50 in 2024 — a 38% depreciation. These currency fluctuations have inflated dollar-denominated equipment prices and amplified project financing costs. Moreover, Japanese short-term policy rates are at their highest level since 2008, with future hikes anticipated in 2026. Although lower financing costs, compared to those in the United States (US) and Europe, have been cited as an advantage for Japanese wind projects, recent increases in debt costs have eroded that benefit.

Additionally, regulatory and permitting barriers further increase overall project expenses. In Japan, it takes 6–8 years from the start of permitting to the commercial operation date for fixed-bottom offshore wind projects. By contrast, the European Union (EU) caps the permit-granting process at two years for offshore projects. Japan’s lengthy baseline lead time increases exposure to component price volatility, rising financing costs, and delays, making projects more costly and risk-prone by global standards.

Like Mitsubishi, other bidders in the third offshore wind auction would likely have faced the same inflationary challenges. However, this case highlights more than just the risks of aggressive bidding. To realize its offshore wind ambitions, Japan should address its high domestic costs and unfavorable auction rules that incentivize low bids.

Auction price comparisons: Japan vs. international benchmarks

Japan’s first offshore wind auction in 2021 highlighted the stark disparity between domestic and international prices. Bidding prices in Japan’s first round were between JPY11.99/kWh and JPY24.5/kWh. This was two or three times higher than international benchmarks, such as the United Kingdom’s (UK) 2021 Round 4 bid at GBP37.35 per megawatt-hour (MWhGBP37.35 per megawatt-hour (MWh) (around JPY7–8/kWh) or Germany and Taiwan’s Round 3.2 with zero-premium bids. A zero-premium bid refers to an auction scheme in which developers bid with a premium — defined in the support scheme as a subsidy — set at zero, and proceed with the project solely based on revenues linked to wholesale electricity market prices.

At first glance, Japan’s results appear uncompetitive. However, the higher ceiling prices set by the government reflected the country’s unique conditions rather than an intentional distortion. Japanese developers must pay for grid connections and seabed reinforcement, which are often covered by governments in Europe. Long permitting timelines and coordination with fisheries extend project risks, raising financing costs. The absence of inflation indexation forces bidders to price in uncertainty, while dependence on imported turbines exposes them to exchange-rate and shipping risks.

Japan’s high auction prices are the product of systemic design and cost burdens, not technological inefficiency. Recognizing these differences is essential to understanding why the country’s offshore wind auctions are more expensive compared to its global peers. It also underscores why recent government reforms aimed at correcting low-price competition and easing structural burdens will be critical for unlocking Japan’s true offshore wind potential.

Evolution of Japan’s offshore wind policy framework

The Japanese government has started amending its offshore wind policy framework in response to the issues revealed in Round 1 bidding. In January 2025, it revised core auction guidelines to address excessively low-price bidding and project delays. The new rules allow developers to reflect up to 40% of cost inflation in the electricity price between the auction and the start of construction. For projects allocated from Round 4 onwards, bid bonds for operational delays increase from JPY13,000 per kilowatt (kW) to JPY24,000/kW — double that of projects assigned from Rounds 1 to 3 — and are structured as phased penalties to discourage speculative bidding and ensure project completion. Scoring criteria have also shifted from a price-only evaluation to factor in feasibility and local contributions.

Moreover, in November 2025, the government announced seven measures to enhance the bankability and completion prospects of offshore wind projects. These include a provision that zero-premium projects in Rounds 2 and 3 will be allowed to participate in the Long-Term Decarbonization Power Source Auction, securing 20 years of capacity revenue. The price-adjustment mechanism will continue to reflect only future inflation. Developers may also revise key equipment, including turbines, in cases of supplier withdrawal or significant cost escalation. Additional measures include more flexible base port rules, “renewal in principle” for occupation permit extensions, improved valuation of renewable attributes, and integrated grid, port, and financial support for low-carbon investments.

Strengthening domestic supply chains

METI also aims to reinforce domestic supply chains through initiatives, such as the July 2025 memorandum of understanding with Vestas and Nippon Steel, to localize turbine component production. The government has also pledged to reauction the sites abandoned by Mitsubishi under these new rules.

The initial bidding rounds highlighted the cost risks associated with weak domestic supply chains. Japan could address both exchange rate impacts on wind farm costs and the need to localize the offshore wind supply chain by domestically sourcing steel, foundation and tower fabrication, and other key components in the balance of systems and services. Beyond the turbines themselves, these inputs and services account for 60% to 70% of total project expenses. Japan’s advanced steel production, fabrication, integration, project management, and logistics systems are well-suited to meet offshore wind demands. The country’s shipbuilding sector could also benefit from producing specialized vessels needed for offshore wind farm installation and maintenance. Additionally, Japan is home to leading global suppliers of key components for cabling and transmission system elements, especially high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission components. As the offshore wind auction market matures and scales, the advantages of onshoring or localizing a greater share of wind turbine manufacturing and assembly become increasingly clear.

Expanding the scope for offshore wind projects

In June 2025, the Japanese parliament passed a law allowing the installation of offshore wind farms in the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This is a significant development as it effectively expands the geographical scope for future auctions beyond Japan’s territorial waters, opening vast new areas for large-scale offshore wind development. With one of the world’s sixth-largest EEZs, Japan could now access deeper and windier sites with higher capacity factors and lower seasonal variability, giving new momentum to its long-term offshore wind ambitions.

The government is considering reauctioning the three sites in Akita and Chiba that were awarded in Round 1, following Mitsubishi’s withdrawal from the projects.

Simultaneously, attention is turning to the upcoming Round 4 auction. Two new offshore areas near Matsumae and Hiyama in Hokkaido have been designated as promotion zones, and a public tender is expected for these sites. However, the government postponed the launch of Round 4, initially scheduled for 14 October 2025. The delay is intended to provide time to assess the reasons behind developers’ withdrawal from the three Round 1 sites and to establish conditions to ensure offshore wind investments can reach completion. Therefore, the postponement is not a setback, but a constructive step toward refining the auction framework and fostering a more sustainable market environment.

Optimistic outlook for the sector

Despite these headwinds, other renewable energy developers remain optimistic about the long-term outlook for the sector. At a recent industry event, Masato Yamada, Senior Vice President at JERA Nex bp Japan Ltd., remarked, “There’s a perception that offshore wind power is dead, but the initiative hasn’t even truly begun.” Regarding the company’s Round 2 project off the coast of Akita, he further noted that withdrawing would result in greater losses, making continued development the rational choice. His comments underscore that, despite recent setbacks, developers still have strong incentives to move projects forward.

In fact, not all projects are stalled. Round 2 developments are progressing despite cost headwinds: Mitsui & Co. has selected its EPC contractor and plans to begin onshore construction in October 2025, Tohoku Electric is moving ahead with its 615MW Aomori project, and the Oga–Katagami–Akita consortium led by JERA Nex bp Japan has established a local headquarters with operations targeted for June 2028.

Round 3 developments are also progressing in line with planned construction and operation timelines. The consortium led by JERA is preparing fisheries impact assessments for its project off the southern coast of Aomori in the Sea of Japan, while Marubeni’s project off Yuza, Yamagata Prefecture, is moving forward on a similar schedule. Both projects target commercial operation in June 2030 and plan to use Siemens turbines. In June 2025, METI and Siemens Gamesa established a cooperation framework to discuss and promote the development of a wind turbine supply chain for the Japanese market and overseas expansion. Together, these efforts signal growing momentum toward strengthening Japan’s offshore wind industry through international collaboration and supply chain development.

These examples demonstrate that, alongside policy reform, tangible progress continues, highlighting that Japan’s offshore wind sector may be down — but is far from out.

Yet limitations remain

Despite the visible progress in Round 2 and the reforms introduced, Japan’s offshore wind developers still face structural headwinds. The latest measures — including the provision of 20 years of capacity revenues for zero-premium projects in Rounds 2 and 3, the allowance of turbine substitutions in the event of supplier withdrawal, and the shift toward “renewal in principle” for occupation permit extensions — are crucial mechanisms to reduce cancellation risks and improve financial visibility. However, these relief measures apply only to Rounds 2 and 3; from Round 4 onward, developers will return to a highly competitive environment.

At the same time, many of the fundamental bottlenecks identified by industry and in the Global Wind Energy Council’s (GWEC) recent white paper remain unresolved. These include:

(1) Insufficient inflation protection that does not compensate for past cost escalation, in stark contrast to the UK’s fully Consumer Price Index (CPI)-adjusted Contract for Difference (CfD)

(2) An underdeveloped corporate power purchase agreement (PPA) market and the absence of credit-guarantee schemes that constrain access to higher-priced offtake

(3) A lack of compensation mechanisms for curtailment risk

(4) The absence of a strategic offshore transmission plan and persistently high grid-connection costs

(5) Shortages of domestic ports and installation vessels, which continue to force developers to rely on costly foreign charters

(6) Regulatory inconsistencies — such as the implicit application of building standards — that prolong certification and permitting timelines, delaying revenue generation

Unless these structural issues are resolved, development costs will remain elevated, permitting will remain protracted, offtake options will stay limited, and incentives for meaningful domestic supply chain investment will continue to be weak. Addressing these challenges would establish a solid foundation for the long-term growth and stability of the offshore wind market and send a strong signal to domestic manufacturers to invest in localizing supply chains. Mitsubishi’s withdrawal showed that the difficulty was not only aggressive bidding but also weaknesses in the auction framework. With further institutional improvements, Japan can still realize its offshore wind potential. Accelerating climate policy and innovation in this sector will be essential to sustaining the country’s future competitiveness.