Since the early 2000s, scientists have been puzzled by a gleaming turquoise spot in the middle of the Antarctic Ocean showing up in satellite images.

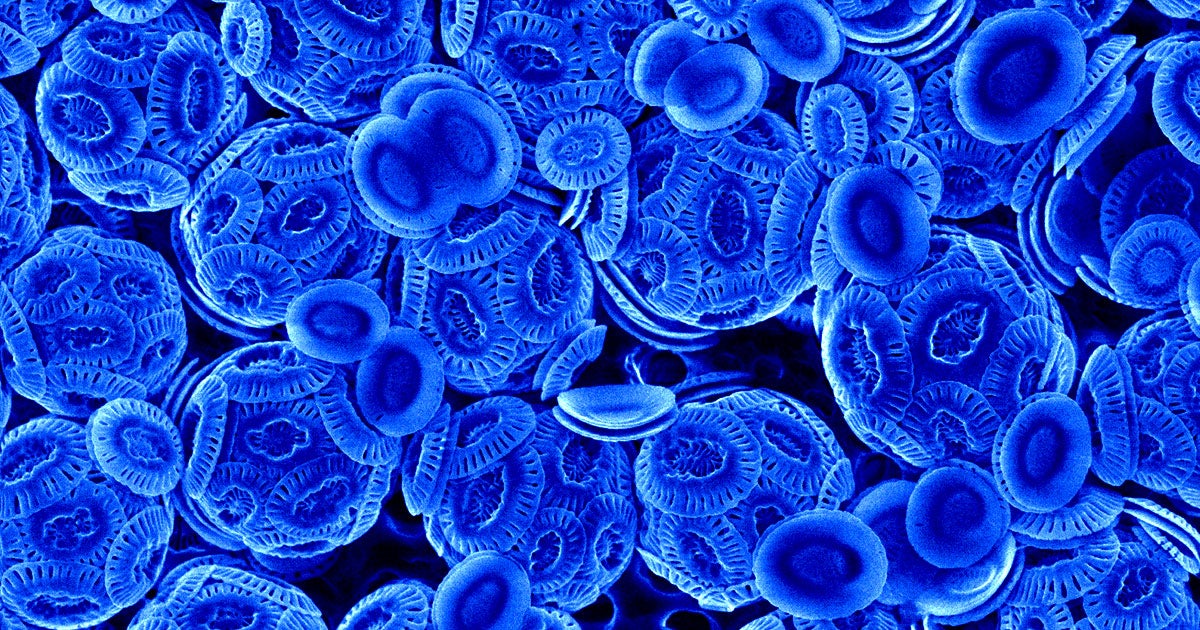

The patch is located just south of the great calcite belt, a region that’s rich in the mineral form of calcium carbonate, and teeming with coccolithophores, tiny marine organisms that grow reflective calcite shells out of the mineral.

The patch itself, however, has been considered far too frigid to support these tiny plankton, causing a longstanding marine mystery.

Now, as detailed in a paper published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles, scientists say they’ve finally nailed down a possible reason for the existence of the otherworldly iridescence.

The team ventured into the rough ocean waters on board a research vessel, taking detailed measurements at various depths to collect data that satellite images can’t provide.

“Satellites only see the top several meters of the ocean, but we were able to drill down with multiple measurements at multiple depths,” said Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences senior research scientist Barney Balch in a statement about the research.

To their surprise, they found that coccolithophores did, in fact, live in the frigid waters where no one thought they could survive — albeit in much smaller concentrations than in the great calcite belt. In the process, they got an unprecedented peek at how the ocean’s carbon cycles function.

Coccolithophores are caught in a massive war with another type of plankton, called diatoms, which turn organic carbon into energy, a vital source of food for marine life.

The border between the great calcite belt and the mysterious turquoise region was previously seen as a kind of no man’s land between these two factions of plankton.

But the researchers’ findings suggest that “moderate concentrations of plated coccolithophores and detached coccoliths were observed south of the great calcite belt all the way to 60°S,” the paper reads.

However, the majority of the reflectiveness is the result of the shiny outer layers of diatom plankton scattering the light, the researchers posit.

The findings could have considerable implications for our planet. Coccolithophores are so widespread, they’re considered a critical sink for atmospheric carbon.

“We’re expanding our view of where coccolithophores live and finally beginning to understand the patterns we see in satellite images of this part of the ocean we rarely get to go to,” Balch explained in the statement.

“There’s nothing like measuring something multiple ways to tell a more complete story,” he added.

More on plankton: Scientists May Be Able to Fight Global Warming by Supercharging Plankton