Korea’s interconnected PF structure

In Korea, real estate project finance (PF) is a financing method used primarily for large-scale real estate development projects. Unlike traditional corporate finance, project finance is typically structured around a specific project, with repayment of debt relying on the cash flows and assets generated by the project itself, rather than the general creditworthiness of the developer. Unlike advanced economies where developers typically contribute 30–40% equity to real estate PF projects, Korean developers often inject as little as 5% or less of the total project cost, hence financing the remainder through debt.

Given the inherently high risk and uncertainty of PF projects, financial institutions are reluctant to lend without guarantees, placing greater emphasis on guarantees instead of conducting comprehensive assessments of project feasibility. These guarantees are often provided by construction companies. With the enhancement of the project’s creditworthiness, developers can better secure the necessary financing (Figure 1). Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) too extended credit to the developers but they tend to focus on riskier projects in search for higher returns.

In light of these credit guarantees, a construction company is obligated to assume the responsibility in the event where financial institutions refuse to extend the loan maturity or the developer becomes insolvent. In such cases, the construction company’s deteriorating financial condition may trigger a credit crunch across the construction sector, potentially creating ripple effects that affect the broader financial system. This was evident In late 2023 when Taeyoung Construction, Korea’s 16th largest builder, entered a debt workout which fueled concerns of a funding squeeze in the construction sector leading to financial market volatility.

PF stress across NBFIs and construction

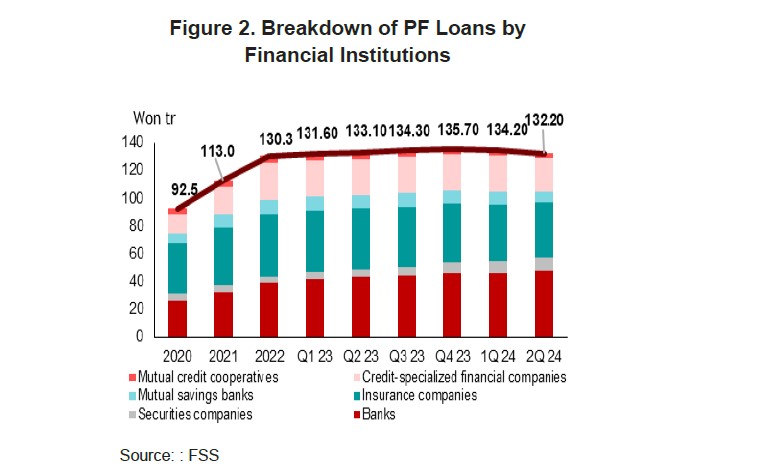

The current challenges faced by real estate PF have their roots in the mid-2010s, when a real estate boom was fueled by low rates. During this period, both banks and NBFIs aggressively expanded their PF lending. By Q2 2024, Korea’s PF loans stood at KRW 132.2 trillion, with 63.5 percent held by NBFIs and 36.5 percent by banks (Figure 2). Among NBFIs, savings banks and credit cooperatives targeted higher-risk market segments and lending to lower-credit borrowers.

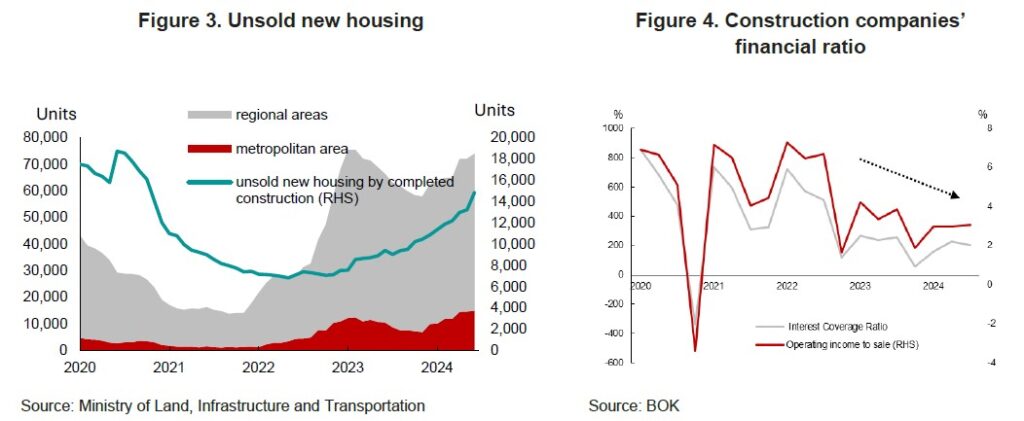

However, this landscape changed dramatically in mid-2021, as aggressive rate hikes and rising construction costs inflated presale prices and dampened real estate demand. Inventory of unsold units rose sharply, especially in non-metropolitan areas (Figure 3). As unsold units accumulated, developers and construction firms faced worsening liquidity, triggering contingent liabilities and forcing costly financing or asset sales. This placed additional strain on already weakened construction companies and eroded their profitability (Figure 4).

For example, Taeyoung Construction’s debt-to-equity ratio was 258 percent, with KRW 3.7 trillion in PF guarantees (374% of its equity) as of end-September 2023, prior to filing for a debt workout in December.

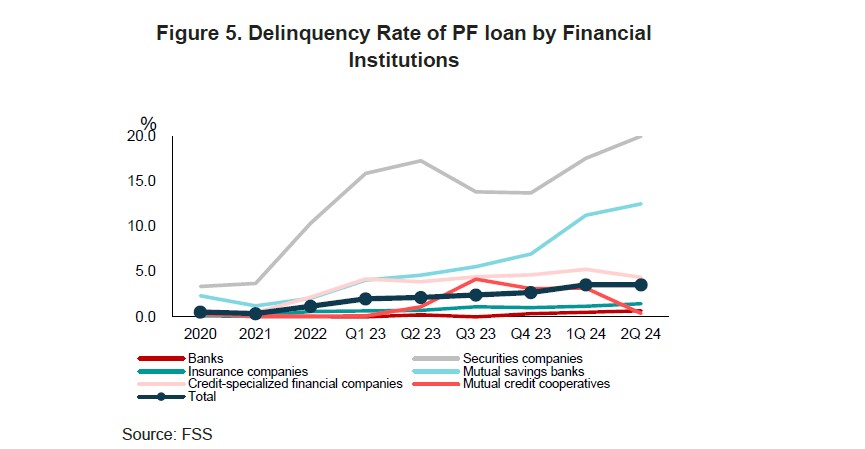

As construction companies’ repayment capacity weakened, NBFIs with large exposures to PF loans saw a sharp rise in delinquencies. Particularly hit were savings banks whose non-performing loan (NPL) ratios surged from 3.4 percent at end-2021 to 11.5 percent in June 2024. Securities firms also recorded growing PF loan delinquencies, reflecting broader vulnerabilities across the NBFI sector (Figure 5).

Policy response and challenges

The accumulation of PF-related distress has led to a sharp downturn in the property market and triggered broader stress across the construction and financial sectors. In 2024, the Korean authorities rolled out extensive policy measures to reduce market uncertainty surrounding real estate PF and to ensure its orderly soft landing.

- A “soft landing” package centered on differentiating viable and non-viable projects through enhanced feasibility reviews.

- Broader reforms to shore up the PF sector’s structural resilience, including raising efforts aimed at bringing equity ratio in line with advanced economy standards (of 20 percent) over the medium to long term.

As a result, as of December 2024, KRW 6.5 trillion—30.9 percent of the KRW 20.9 trillion in loans to development projects classified as “attention” or “insolvency risk” had been resolved or restructured.

These efforts contributed to improvements in key financial soundness indicators, including a decline in both the NPL ratio and PF delinquency rates for two consecutive quarters. However, with the real estate market still underperforming, new non-performing assets are expected to emerge.

The authorities must therefore maintain heightened vigilance and continue with the resolution and restructuring of existing NPLs, and implementation of rigorous asset quality management frameworks across all financial institutions exposed to PF risk.