The job hopper and the job hugger: Two distinct species, with one going into hibernation as the other emerges. Bank of America’s latest research shows that the era of the job hopper—once the defining labor market species during the pandemic’s “Great Resignation”—is quickly vanishing. The job hopper’s day was 2022, BofA finds, and even though it doesn’t use the phrase, the report constitutes additional evidence that 2025 is the heyday of the “job hugger.”

Consulting firm Korn Ferry found earlier this month that the careers climate of 2025 has workers holding onto their jobs “for dear life.” This analysis followed a shocking jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for July, which massively revised downward earlier estimates of jobs growth in May and June. Beyond President Trump immediately firing the head of the bureau, it confirmed an economy with minuscule jobs growth.

“Given just all the activity that happened post-COVID and then some of these constant layoffs, people are waiting and sitting in seats and hoping that they have more stability,” Korn Ferry managing consultant Stacy DeCesaro previously told Fortune about the rise of the job huggers. “No one is wanting to leave unless they’re very unhappy or miserable in their job or just feel so unsettled by the company.”

BofA says job hopers are hard to measure but are an important part of the overall labor market picture, and their data shows a clear drop from the peak of the Great Resignation. They find job hopping is still above its prepandemic levels, but that was a very different economy, with just 3.5% unemployment (the lowest since 1969) and an extraordinarily tight labor market. In retrospect, that was the end of a long period of economic expansion, with elevated job stability and reduced urgency for changing jobs, before the pandemic changed the picture dramatically.

A big helping of ‘meh’

BofA Research used aggregated and anonymized deposit account data across millions of customers to track job-to-job, or “J2J” moves, identifying the rate by identifying changes in payroll within deposit accounts. It aligns with federal data from the JOLTS survey, which tracks the “quits rate” every month, showing that July’s quits rate was the lowest level since December. Posting on Bluesky, Glassdoor chief economist Daniel Zhao wrote that the report “shows softer figures with hires and quits rates still sluggish. Not dire, not amazing, more meh.”

Speaking to Fortune about the general state of the labor market in a new interview, Zhao said Glassdoor’s data shows that “more and more workers are sitting tight in their roles and feeling stuck as a result.”

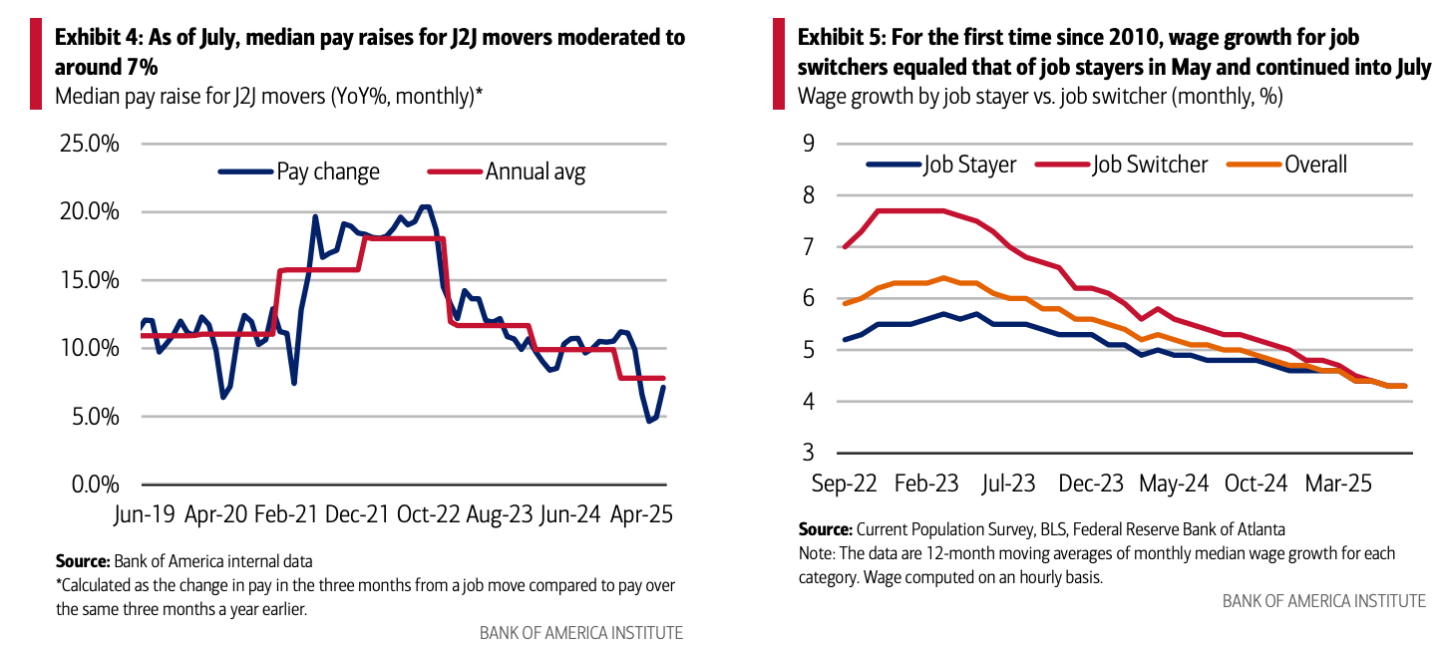

BofA’s latest report finds the J2J move rate fell sharply from its 2022 peak and now sits just 2% higher than pre-pandemic levels—having trended downward most of the past year. Wage increases for job hoppers have collapsed, too, with median pay raises for switchers dropping from 20% in 2022 to just 7% as of July 2025, even dipping below 2019 averages. BofA cites data from the Atlanta Fed showing that from May through July, wage growth for job switchers equalled that of job stayers—the last time this happened was in 2010, during the tepid recovery of the Great Recession.

White-collar chill

BofA’s granular payroll analysis reveals that job changing has cooled dramatically in industries such as finance, information, and business services, where monthly pay periods are prevalent and job moves are rare. Meanwhile, job changing remains a bit stronger in industries including manufacturing and construction, where weekly pay periods and ongoing labor supply issues keep turnover modestly higher. But overall, with the rate of job changers receiving monthly pay dropping and weekly pay outpacing other types, the “white-collar job hopper” is disappearing fastest.

This doesn’t mean workers are satisfied. A November 2024 report from Glassdoor found that 65% of employees reported feeling “stuck” in their jobs, implying that they wanted to job-hop but just couldn’t. Quiet quitting and disengagement are rising, with Gallup estimating that disengagement cost the global economy $438 billion in 2024. Executive turnover adds to the uncertainty—with CEO departures hitting record highs and employees reporting a revolving door at the top. For many, “job hugging” is survival, not loyalty.

The kids are not alright

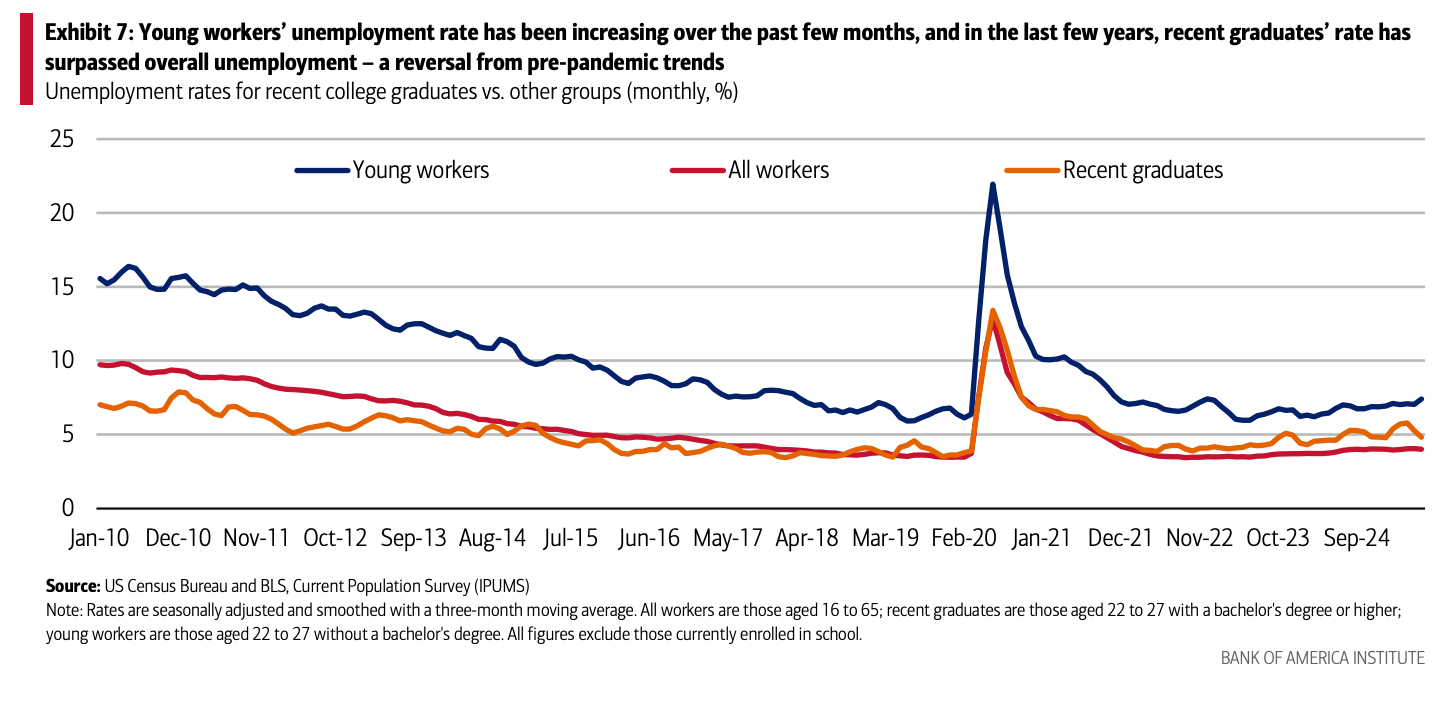

To finish its report, BofA zoomed out to look at younger workers and the plight of Gen Z, noting that over 13% of unemployed Americans in July were new entrants or those looking for jobs with no prior work experience, which skews towards Gen Z. That is the highest since 1988, according to the Richmond Fed. Worryingly, the unemployment rate for young workers has continued to climb, reaching 7.4% in June.

Citing research from the International Labor Organization, BofA argues that young people have suffered higher employment losses than older workers and have quit their studies due to disruptions in education and on-the-job training. A proprietary BofA survey finds younger generations are more likely to be negatively affected by factors related to work/

employment.

Overall, the bank estimates that “some 289 million young people globally are neither gaining professional experience through a job nor developing skills by participating in an educational or vocational program, limiting economic gains.” BofA sees dim employment prospects for young workers in the medium term, given uncertainty from the new tariffs regime, the adoption of AI, and the general drag on entry-level positions.

In this economy, then, the job huggers are betting that there isn’t a better opportunity out there, and the young workers find themselves on the outside looking in. BofA doesn’t project any scenarios in the event of a recession, but with the economy stalling out for job hoppers, the workforce is in white-knuckle mode, holding on tight.