Our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and esophageal-gastric variceal bleeding (EGVB) in cirrhotic patients, revealing shared risk factors and a potential causal link. Key findings indicate that an enlarged portal vein diameter and low hemoglobin levels are independent risk factors for both conditions. Notably, EGVB not only has a higher incidence but also tends to occur earlier than PVT. Importantly, in patients with both complications, PVT often precedes EGVB. Our IPTW analysis further confirms that patients with PVT have a significantly higher incidence of EGVB, establishing PVT as a significant risk factor for EGVB.

In line with prior studies, our findings confirmed that EGVB is more common and occurs earlier than PVT in cirrhotic patients [12, 13]. This is likely due to the progressive increase in portal hypertension during liver cirrhosis, which was central to EGVB development. PVT may further elevate portal vein pressure, thereby promoting EGVB. A predictive model by Zhong et al. identified mesenteric vein thrombosis as a risk factor for gastrointestinal bleeding, aligning with our results and underscoring PVT as a key EGVB predictor [14].

Our study highlights common risk and protective factors for PVT and EGVB. For instance, an enlarged portal vein diameter and low hemoglobin levels were found to be shared risk factors. This suggests that early management of portal vein pressure, reducing portal vein diameter, and improving anemia could help prevent both PVT and EGVB. Interestingly, our study found that COPD serves as a protective factor for EGVB. This could be mediated by medications commonly used in COPD management, such as glucocorticoids, bronchodilators (e.g., theophylline), and diuretics, which may lower portal pressure through various mechanisms. Experimental data indicates that theophylline may attenuate liver fibrosis in rats, possibly by reducing cholesterol accumulation and inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation [15]. However, this finding is based on limited evidence and significant confounding factors (e.g., comorbidities and polypharmacy) cannot be excluded. Therefore, the potential protective role of COPD and its underlying mechanisms require robust validation in future, well-designed clinical studies.

When considering anticoagulation therapy for PVT, clinicians must weigh its impact on EGVB risk. Previous concerns about anticoagulation therapy potentially raising EGVB risk have been alleviated by recent studies, including ours, which suggest that anticoagulation for PVT not only fails to boost EGVB incidence but may even lower the risk of spontaneous EGVB. This underscores the importance of effective PVT management in cirrhotic patients [10, 16].

Moreover, our study explores the complex mechanisms of bleeding and thrombosis in cirrhotic patients. Cirrhotic patients exhibit a “rebalanced” coagulation state, with reductions in both procoagulant and anticoagulant factors. This includes decreased levels of coagulation factors (e.g., fibrinogen and prothrombin), reduced anticoagulant factors (e.g., protein S and protein C), lower platelet counts, and altered platelet function. These factors maintain a precarious balance, yet bleeding and thrombosis risks persist. Other factors that might disrupt this balance include severe anemia, renal failure, systemic infections, and volume overload. Systemic infections and renal failure appear to increase bleeding risk, while the impact of heart failure, a common cause of volume overload, has not been studied due to a small sample size. Recent studies indicate that systemic infections might exacerbate both hypercoagulability and hypocoagulability, highlighting the need for further research on their impact on bleeding and thrombotic events in cirrhotic patients [17,18,19,20].

Routine hemostasis and coagulation tests (e.g., platelet count, PT, and INR) have limitations in accurately assessing the actual bleeding or thrombosis risk in patients. Managing cirrhotic patients demands a comprehensive and meticulous evaluation. Our study shows that PVT and EGVB share common risks and protective factors, suggesting that early control of portal vein pressure, reducing portal vein diameter, and improving anemia might prevent PVT and EGVB. Guidelines recommend optimizing hemoglobin levels in cirrhotic patients by treating iron, folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 deficiencies [9]. Future large-scale observational studies were needed to further explore the link between anemia (alone or combined with thrombocytopenia) and bleeding or thrombotic events in cirrhotic patients.

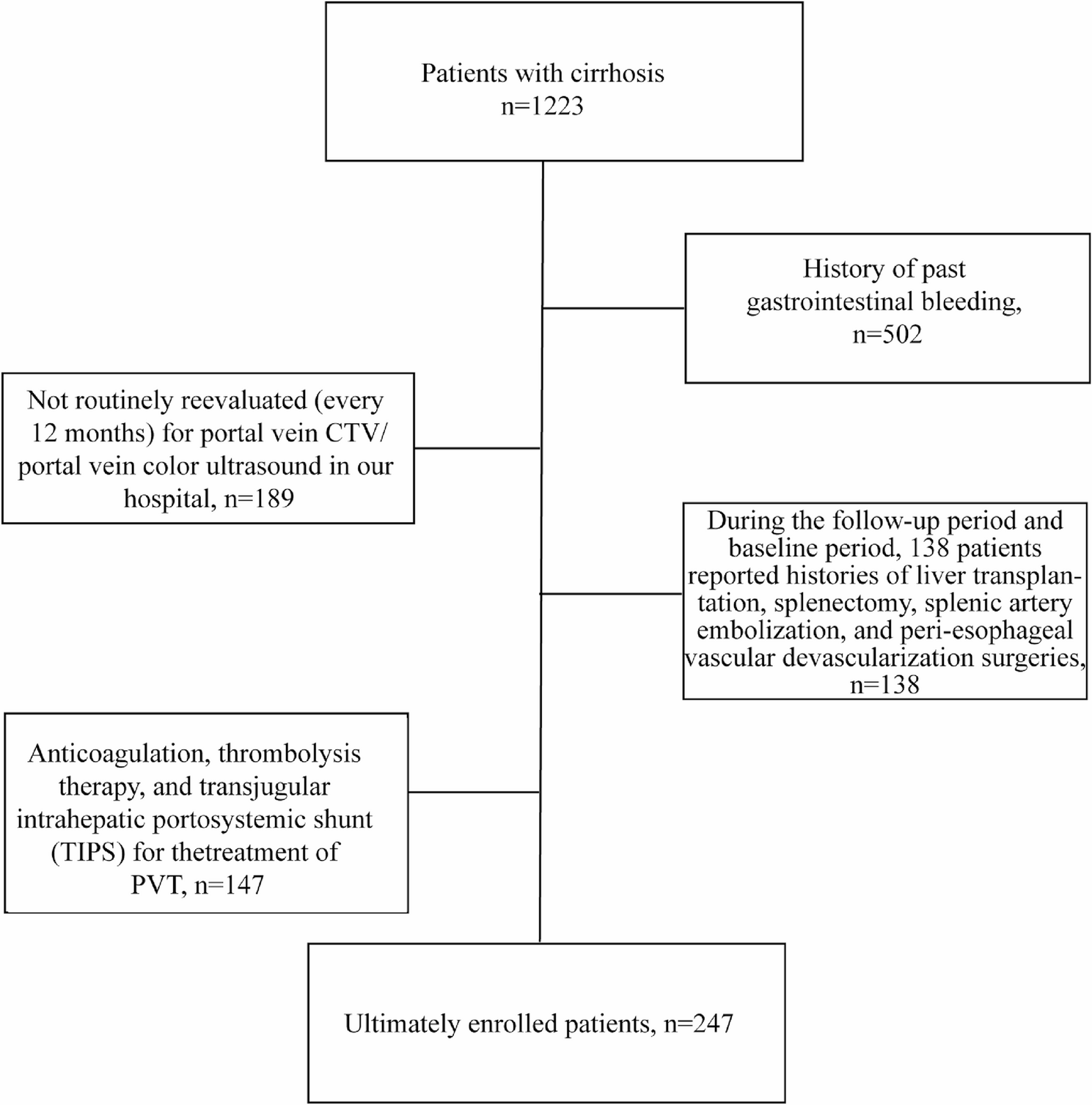

Lastly, our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The retrospective design and single-center nature may have introduced selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the relatively small sample size of 247 patients, although derived from a 10-year data collection period, could affect the power of our statistical analyses and the precision of our estimates. A further limitation relates to the strict exclusion criteria applied to control for confounding factors, such as excluding patients with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, those who had undergone relevant surgeries (e.g., liver transplantation, splenectomy, or TIPS), and including only untreated PVT patients. While these criteria enhanced the credibility of our findings on PVT promoting EGVB by minimizing confounding factors introduced by surgical interventions and focusing on the natural progression of PVT and EGVB in cirrhotic patients, they may have reduced the representativeness of our sample, particularly for advanced cirrhosis cases where such surgeries are more common. The impact of excluding these patients on the outcome is not precisely quantifiable. Residual confounding also cannot be completely ruled out due to the complexity of cirrhosis and its complications. Furthermore, our study included patients without a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, many of whom lacked baseline endoscopic examinations. As per guidelines, primary prophylaxis is initiated based on endoscopic findings. Thus, in our cohort of treatment-naive patients without prior bleeding, there was no systematic primary prophylaxis in place. This limitation restricts the extrapolation of our conclusions to scenarios involving secondary prevention. Additionally, while the portal vein diameter measurements were retrospectively obtained from routine clinical data without blinding, we acknowledge this as a methodological limitation and plan to implement a blinded, multi-observer assessment method in future prospective studies. Lastly, the long follow-up period might have led to changes in clinical practice and management strategies over time, which could have influenced the outcomes. Future research should involve multicenter studies with larger sample sizes to further validate these findings and explore the impact of surgery on the incidence and management of PVT and EGVB across different treatment scenarios.