It was approaching midday and the first-team players at FC Pacos de Ferreira were being put through their paces. They ran and ran under a scolding sun. At the top of the hour, their work done, they walked off, in ones and twos, to seek refreshment and shade.

It looked a lot like a normal day of pre-season training. Just around the corner, though, on Rua do Estadio, the club’s flag flew at half mast. Visible above the west stand of Pacos’ stadium was an electronic billboard bearing a message and a photo.

“Forever,” it read. The photo was of Diogo Jota.

Flag at half-mast outside the Pacos ground

Inside the main stand is the old first-team changing room. The floor is green and white checkerboard, the wooden lockers starting to show their age. It was here, in October 2014, that Jota pulled on the yellow Pacos jersey ahead of his first match in senior football. When he left to join Atletico Madrid two years later, the windfall allowed the club to build new a new eastern stand with more modern facilities.

“We call that the Diogo Jota stand,” explained Paulo Goncalves, the club’s long-serving technical secretary.

The old first-team changing room at Pacos

Outside, Goncalves pointed to the far end of the pitch. “That was where he scored his first goal,” he said. He pointed towards the tribune. “He ran and hugged his mum over there.”

Jota only played 45 times for Pacos. When his career clicked into gear, taking him from this modest club to stardom, he might easily have moved on, cut ties. But his gratitude to Pacos — for launching his career, for taking a chance on him when the country’s big hitters would not — forged a strong connection.

He acted as a ‘godfather’ to youth players during a summer tournament last year, lending advice and support from afar. He would drop in when he was in the area. “He was always in touch, always sending us messages,” said Goncalves, the emotion audible on his voice. “Especially in difficult moments.”

A wreath laid by Scottish Liverpool fans at Pacos de Ferreira’s stadium

One thing that has become apparent since the death of Jota and his brother, Andre Silva, is that everyone has a story about him — little examples of his decency, his humanity, his heart. The tales come from Liverpool, from Wolverhampton, from a hundred other places.

Travelling through the north of Portugal, though, what really struck home was the regionality of this tragedy.

Jota was born in Porto. He spent his childhood in Gondomar, a sleepy satellite city, played for the local team. His grandfather still lives there, down a bumpy path off Rua da Minhoteira. Jota’s parents were in the house next door; the kids learnt to play football in the connecting yard. When Jota left SC Gondomar, it was only for Pacos, 30 minutes away. He later returned to the region with FC Porto. His brother played for Penafiel, another local team. Their father, Joaquim, spent his youth in Foz de Sousa, just to the south. Jota’s widow, Rute Cardoso, grew up in Jovim.

The entire region is in mourning for the loss of two of its sons. For huge numbers of locals, the loss is all the more acute for being personal.

Take Vitor Borges, a taxi driver who worked for years with Jota’s mother, Isabel, at the Ficosa car factory in Porto. “Her and her husband overcame a lot to raise those boys,” he said, shaking his head. “And all of it gone, just like that. No one deserves this, but least of all her.”

Or Miguel Pereira, a former neighbour of Jota and Silva, slightly older but young enough to remember kick-arounds at the red asphalt court at the top of their road. He brought up a photo on his phone: his son Vasco with Jota, taken in May 2024. “It was a year ago but it feels like yesterday,” he said.

Pereira had come to the headquarters of Gondomar SC to pay his respects. Vasco and his cousin Goncalo play for the club’s under-eight team. They recently won their local league title and had brought a replica of the trophy with them to lay down in tribute. They wound a Gondomar scarf around it before setting it down.

Goncalo and Vasco Pereira prepared their tribute

Gondomar’s academy is named after Jota. His face adorns the side of the main stand. On the clubhouse there are images of him as a boy, in Gondomar’s shirt, and as an adult, playing for the Portugal national team. On Friday afternoon the site had been transformed into a temporary shrine. There were flowers, candles and scarves, photos and drawings. There were football jerseys bearing messages written in marker pen. “You will always be our hero,” read one. “Diogo and Andre, forever sons of this land,” read another.

At the back of the main stand is a training pitch, the astroturf degraded, and an old club minibus. Jota played here between 2005 and 2013; there’s a good chance that minibus took him and his brother to games in nearby towns, their paths criss-crossing the foothills.

Tributes outside the academy at SC Gondomar’s stadium

On the main pitch, the sprinklers were on. Six starlings perched behind the goal. Through the main gate, more people came: two teenage girls in Liverpool shirts, three young men on their lunch breaks.

Pedro Figueiredo, a Porto fan, had felt an urge to pay his respects. “He played for my club and I admired him a lot,” he said. “He came from nothing and worked immensely hard.”

Eugenia Dias had brought her granddaughter, Bernadita. They laid a hortencia down together. “Diogo was an idol to the people of Gondomar,” she said. “My son played with him when they were small, maybe five or six. We’re all in mourning. We felt he was ours, in a way.”

A tribute from a child at SC Gondomar

A sign just off the main route into Gondomar informs you that this is Portugal’s goldsmith capital. There are around 450 businesses producing jewellery in the city. Their products are sold around the globe.

There is an obvious resonance here. Not just because Jota was a gem but because he needed working; we are not talking here about a sure thing, one of those kids who was only ever going to be a superstar. He was still playing for Gondomar at 17. Porto did not want him, hence the move to Pacos. His was a grinding, blue-collar path to the top. It made it all the more meaningful to those who followed it.

“He was a humble man, someone who fought for everything he had in his life,” said Gondomar resident Maria Nogueira. “He was a symbol of the region.”

She was stood outside the Matriz de Gondomar church. It was Friday afternoon, just before 4pm. The public wake for Jota and Silva was yet to start but already a large crowd had gathered. Some people strained for a view of the chapel, for a sight of the family. Others took shelter under trees.

The scene outside the chapel in Gondomar

When the doors opened, people formed a line. They waited in the afternoon heat: men in polo shirts, men with walking sticks, women with flowers, families. They kissed their neighbours and friends, shared pallid smiles. They came to leave wreaths, to say prayers, to say nothing at all, to be silenced by the senselessness of it all.

“I just thought it was important to pay tribute,” said Fernando Eusebio, who wore a Porto shirt and admitted he did not know how he would react to seeing the coffins inside. Another man clutched a large bouquet to his chest. He said he was a childhood friend of Cardoso, Jota’s widow. The sentence got caught in his throat; he struggled to get the last words of it out at all.

As the public entered, friends and relatives of the family began to depart. There was a girl, wrapped in a Portugal flag, crying. The Porto president Andre Villas-Boas was ashen-faced, as was Diogo Dalot, Jota’s Portugal team-mate. At the chapel’s exit, an elderly woman wiped away tears. Her husband stared into space.

Their devastation was comprehensible. The scene inside — Jota’s parents sobbing, Cardoso stricken by grief — was one of almost unbearable sadness.

When the church bells rang at 5pm, the queue was still growing, people arriving at the end of their work days, wearing suits and supermarket uniforms, exhausted but present. They kept coming, too, the line eventually winding around the side of the cemetery, the flow only slowing when the sun had finally begun to tire of its own vigil.

Flowers and tributes outside the chapel in Gondomar

The following day, the funeral would bring further emotion. New faces, too: the Liverpool delegation, more of Jota’s Portugal team-mates, flown in from the four corners of the globe. Ruben Neves and Joao Cancelo played in Florida on Friday night at the Club World Cup and were here at 10am on Saturday morning. It would be a world event — testament, in its way, to football’s reach, as well as to the breadth of lives touched by Jota.

Being here, though, among the queuing locals, it was impossible not to think about roots: those that ground us, that keep us connected to where we come from, if we allow them to. It is obvious that Jota nourished his. Cherished them, too. That, far more than his ability as a footballer, made these people love him.

For the family, there is only pain, as raw as it is unjust, a wound they cannot even yet fully comprehend, let alone cauterise. But later, you hope, that will soften into gratitude — for the 28 years they had with him, for the memories, for the beauty he gave not just to their lives but those of so many others.

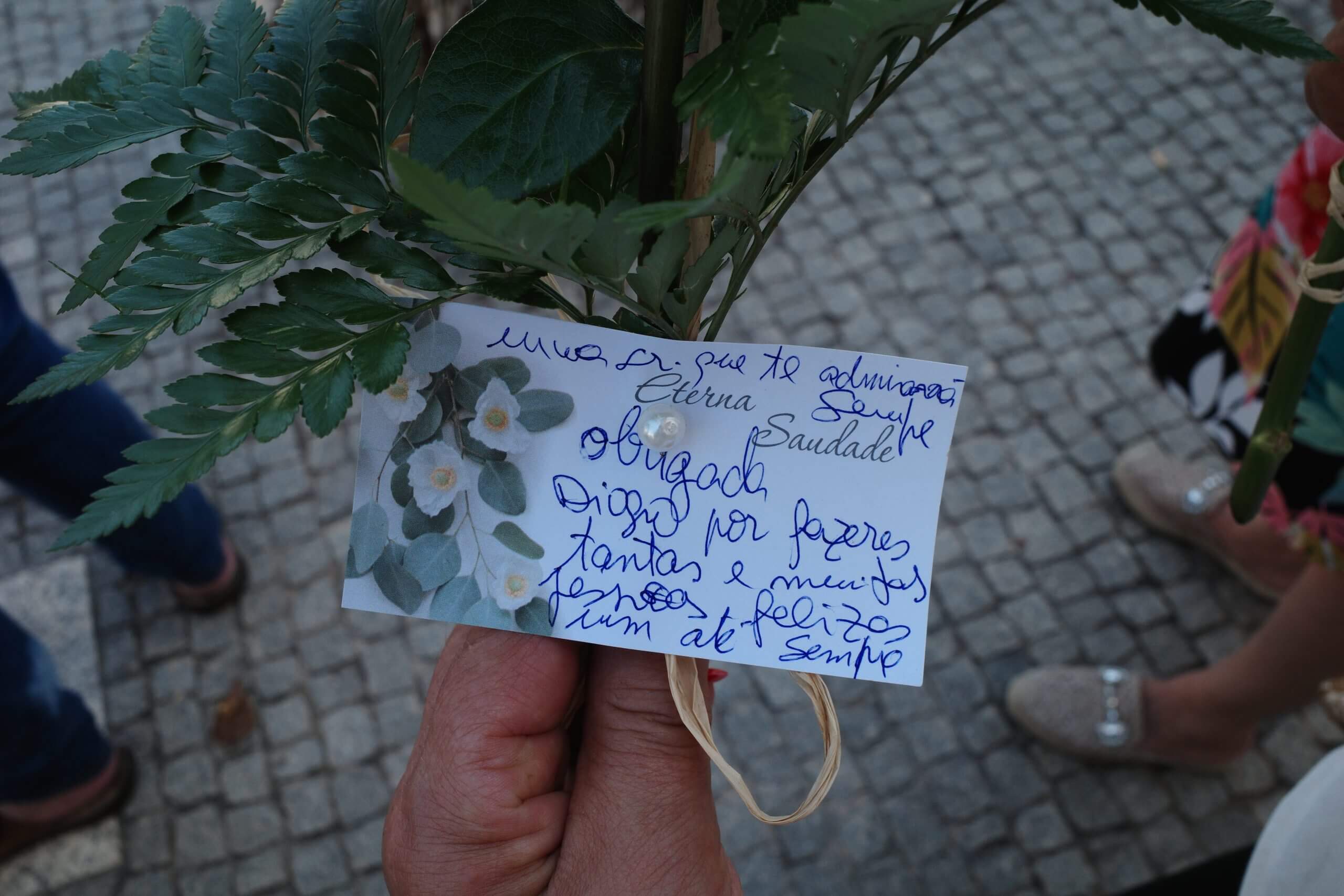

Waiting to enter the chapel and say a prayer for Jota, Maria Nogueira held a bunch of flowers with a note attached.

Maria Nogueira’s flowers and message

“Thank you, Diogo,” it read, “for making so many people happy.”

(All photos: Jack Lang/The Athletic; Illustration: Demetrius Robinson / The Athletic; Top Photos: Rene Nijhuis/MB Media, Octavio Passos/Getty Images, Jack Lang/The Athletic)