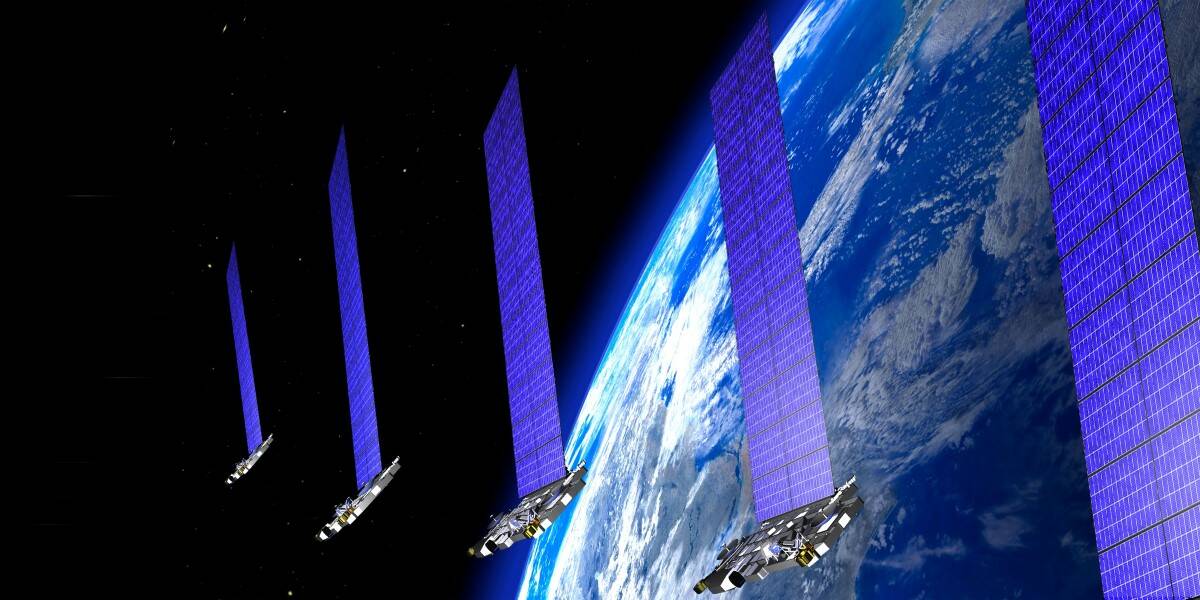

Asia In Brief A SpaceX executive has claimed that a Chinese satellite launch came within 200 meters of hitting a Starlink satellite.

“A few days ago, 9 satellites were deployed from a launch from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in…

Asia In Brief A SpaceX executive has claimed that a Chinese satellite launch came within 200 meters of hitting a Starlink satellite.

“A few days ago, 9 satellites were deployed from a launch from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in…