Viktor Shklovsky’s Journey to the Land of Movies, originally published in 1926, is Ostranenie for kids. The Russian literary critic’s neologism – ‘making-strange’ – with its various German and English translations and interpretations, particularly via his friend Sergei Tretyakov and his pupil Bertolt Brecht, is one of the most influential and misunderstood theoretical terms of the twentieth century. Perhaps the most common misconception is that it means ‘difficulty’, something intractable and unpleasant that must be overcome in order to reach understanding. While Shklovsky’s concept does entail some kind of spanner being thrown in the works of a novel, play or film – a disruption of the rote, the familiar, the automatic – it is, in his version, an avant-garde ‘device’ that can be perceived and understood by anyone, a technique, he argued, used by comedians and circus performers: alienation as fun.

For Shklovsky, Ostranenie was so simple that a child could understand it, and this children’s book was a test case. It tells the story of a Russian teenager named Kolya, a migrant worker who travels to Los Angeles, where he accidentally finds himself having various adventures on the menial fringes of Hollywood. Shklovsky’s style here – short, simple but frequently paradoxical paragraphs, made up of one, two or three sentences – is much the same as in his fictionalised memoirs-cum-formalist manifestos such as Sentimental Journey or Third Factory. A typical, scene-setting passage is a miniature exercise in taking something familiar – in this case the Hollywood film set, seen regularly by millions – and making it ‘strange’:

America has many cities, but Los Angeles is the most interesting . . . the most marvellous thing about Los Angeles is that there are several streets where one cannot live: houses on those streets have only one wall, with a hole in the rear.

The houses all look different: there are Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian ones – even the Moscow Kremlin.

These houses are not made for living, but for making movies.

The Shklovskian ‘laying bare of the device’ – drawing attention to the underlying construction of an artwork, rather than its surface – here extends to an account of how cinema works. There is a detailed explanation of why black and white are reversed in a negative, and of editing, using Lev Kuleshov’s ‘Eccentrist’ caper film The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) as exemplar: ‘the film is gathered from different units, like a coin collection’, Shklovsky tells his imagined young reader, before adding the unexpected detail: ‘the strips are glued together with a special glue that has a pear flavour’.

Early in his career, Shklovsky – an activist of the peasant-populist Socialist Revolutionary party – was keen to deny any necessary connection between art and politics. Of course, when his ideas were picked up by Tretyakov and, subsequently, Brecht, this apoliticism was dropped, with the claim now being that defamiliarization could have a clarifying, awakening effect that could politicise the reader, rather than merely making them more attentive to the outside world and to literary interpretation of it. Shklovsky’s children’s book suggests that by the mid-1920s, he was moving in this direction himself. Journey to the Land of Movies showcases the dialectic of ‘Americanism’ so typical of Soviet art of that era: reverent depiction of the USA’s advanced technologies and its popular art, combined with curt descriptions of homelessness, racism and poor working conditions on the Hollywood studio lots. Charlie Chaplin – about whom Shklovsky published a short book a year earlier – appears, in a little sketch on class and fame: ‘on the screen we can see him fooling the rich and the powerful, hitting them and making fun of them – and we all love him’, writes Shklovsky: ‘but today he’s worlds apart from a workman. He earns millions per year’. The only character in the tale described at length other than our hero is Sam, a black stunt actor, who reveals to Kolya the secret tricks of the Hollywood ‘special effect’, as in a delightful scene where he demonstrates how to ‘walk on the ceiling’.

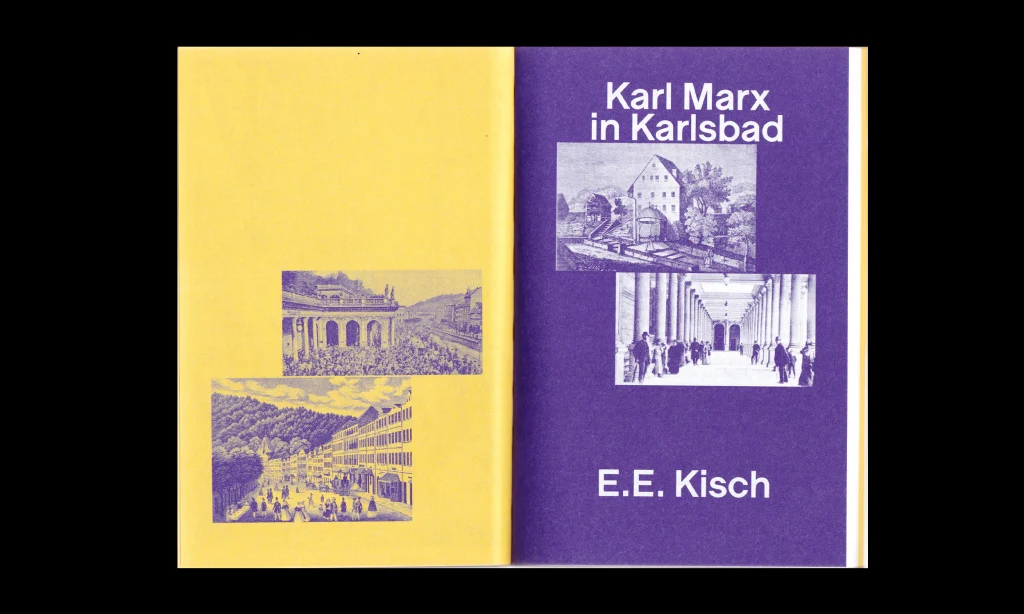

This little rediscovery is the latest from Rab-Rab Press, one of the most consistently unusual English-language leftist publishers over the last decade or so. Translated by Adam Ranđelović and Mikko Viljanen in 2017, as one of Rab-Rab’s first books, this new edition of Journey to the Land of Movies is paired with an afterword by Dahlia El Broul, and features the original, faintly Dadaist line drawings by Dmitry Mitrokhin. Among Rab-Rab’s other recent books are the veteran Marxist historian Jairus Banaji’s Wanting Something Completely Different, a series of short sketches on socialism, anti-imperialism, history-writing and culture, ranging from the Soviet avant-garde to 1960s Lebanon and India, and including some acute and occasionally eccentric judgements; Optically Suspicious, a pocketbook that showcases the avant-garde designs of workers in the typographers’ union of pre-war Yugoslavia; and an edition of Egon Erwin Kisch’s Karl Marx in Karlsbad, a gently ironic account of Marx’s holidays to Karlovy Vary, accompanied by an essay from Hannah Proctor and Sam Dolbear. There is a logic – an emergent political aesthetic – to this apparently eclectic assemblage, if you look closely. All are attractively, sometimes puzzlingly designed; all are ostensibly somewhat esoteric in subject but feature economical, accessible, often goofily amusing writing; and all take an oblique approach to revolutionary history and the various attempts at creating a socialist culture, resurrecting it in select fragments, together forming what Banaji has elsewhere called a ‘Marxist Mosaic’, a coherent picture made up of shards.

The historical avant-garde, Eastern European socialist experiments and Third World revolutions are recurring subjects of Rab-Rab’s books, without any apparent sectarian allegiances. There’s a clear interest in safeguarding the leftist avant-garde from museumification: a translation of the Czech Constructivist, critic and Marxist Karel Teige’s 1936 diatribe The Marketplace of Art is accompanied by a contextualising volume on its applicability to today’s art market. The cross-currents rather than the divides of the Cold War are emphasised, and tourists of the revolution appear at various points; a cast ranging from E. P. Thompson to Cornelius Cardew are taken rather more seriously for their engagements with ‘real socialism’ than they have tended to be by liberal received opinion. A reprint of the Thompson-edited The Railway – An Adventure in Construction, collectively written by the British volunteers who helped rebuild rail connections in post-1945 Bosnia, sits alongside From Scratch – Albanian Summer Picaresque, a collection of materials about the British Maoist musicians who apparently brought free improvisation to Hoxha’s Albania in the mid-1980s. The Soviet avant-garde is a frequent point of reference, but approached from the formalist fringe, as in the remarkable Coiled Verbal Spring, an anthology of writings about Lenin’s prose by formalists including Shklovsky, Eikhenbaum and Tynyanov; or Bie-Bao, a multi-part series on the Georgian futurist and enthusiast for ‘trans-sense’ Zaum poetry, Ilya Zdanevich – one of the strangest figures of that movement, revealed in these small volumes to be a revolutionary among émigrés.

The geography of Rab-Rab stretches from Finland – in Aleksandra Kollontai’s My Heart Belongs to the Finnish Poor, or Hjalmar Linder’s Bourgeois with a Heart, a book that broaches the still-taboo subject of the ‘White Terror’ that followed the suppression of the Finnish Revolution of 1918 – to Beijing, in The Conclusive Scene, a hair-raising account of Mao’s final meeting with the Red Guards in 1968, the notorious event in which Mao, upon hearing a student tell of the ‘black hand’ who had sent the city’s workers into battle against the guards, asserted that ‘the black hand is nobody else but me!’ Rab-Rab’s distinctive internationalism perhaps reflects the background of its publisher, Sezgin Boynik: now based in Helsinki, he studied in Istanbul and was born in Kosovo in 1977, raised in the dying years of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Rab-Rab books are obviously not introductory – it is hard to imagine what anyone not already broadly familiar with the contours of the socialist movements of the twentieth century would make of these volumes – but they are never academic, never arcane for the sake of it. Most, like Journey to the Land of Movies, are tiny, ready to be shoved in the pocket. Others – like Banaji’s anthology, or the volume on Mao and the Red Guards – are printed in A4, and look like corporate reports from a parallel universe; Kollontai’s My Heart Belongs to the Finnish Poor folds out into a poster. Often, texts are distributed for free, as PDFs, as with the translation earlier this year of Berta Lask’s 1925 play Thomas Müntzer: Dramatic Depiction of the German Peasants’ War of 1525; intended for performance, it has already been staged in Glasgow.

Rab-Rab’s designs embody a distinct ethic of their own. The covers and layouts, by the Estonian graphic designer Ott Kagovere, evoke zine culture and post-punk design, without any ostentatious, kitsch tributes to the original sources – no David King-style neo-Constructivism here. Colours are limited, printing techniques are simple, and the publishers are always keen to let you know what the typeface is (in Journey to the Land of Movies, we’re told it’s Niina by Patrick Zavadskis, and Turist by Tüpokompanii). The books have a rough physicality, a smell and a texture to them, palpably having been printed on an actual printing press. This has its own politics, given the extraordinarily poor quality – in simple terms of paper and binding – of so many printed books today. In this respect, the little volume on the Yugoslav typographers’ union seems particularly significant: a reach back into the past, from one group of workers with print to another a century ago, equally proud of their craft. There’s an emphasis on the deliberate, in an era when automatism – the learned, unthought-out response, the treatment of the radically, disturbingly strange and novel as something familiar and eternal – has reached levels Shklovsky could never have imagined in his worst nightmares.

Read on: JW McCormack, ‘Where to Begin?’, Sidecar.