This study reports novel findings on the impact of hormonal-related symptoms on perceived work productivity across cyclical hormone fluctuations and the willingness to engage in menstrual health programs among females of reproductive age working in the U.S. The findings demonstrate that hormonal-related symptoms are experienced throughout all hormonal phases, with symptom severity varying by demographics or menstrual experiences. Despite most participants reporting menstrual pain, nearly half felt ‘very to extremely’ equipped to manage their hormonal-related symptoms. However, perceptions of work-related productivity fluctuated across hormonal phases, being significantly more negative during the bleed and pre-bleed phases and more positive during the late follicular and early luteal phases. After controlling for covariates, higher intensities of hormonal-related disturbances indicated more negative perceptions of productivity. Despite the impact, very few participants reported taking time off from work due to their menstrual cycle. Most participants expressed willingness to engage in menstrual health programming, although their employers often did not provide menstrual-related benefits. Participants preferred learning about menstrual health information from females of similar age or older.

Consistent with earlier studies, our findings showed that most participants in the overall sample reported experiencing menstrual-related pain (91% and 89.5%, respectively) [3, 4]. This was expected as dysmenorrhea is considered highly prevalent [3, 4]. The top two hormonal-related symptoms, in the overall sample, during the bleed phase were fatigue and cramps (uterine or pelvic), which aligns with the broader literature [4, 13, 26,27,28]. Our participants experienced multiple symptoms throughout each hormonal phase, consistent with the limited work evaluating menstrual symptom cluster analyses [29,30,31]. This is crucial as previous work often assessed single symptoms’ impact on productivity loss, potentially missing the real-world experience of concurrent symptoms.

Results from the sensitivity analysis conducted to account for 40% of participants being Exos employees, showed that there were a greater number of symptoms with average intensities that differed significantly across hormonal phases in the overall sample compared to the non-Exos sample. The smaller number of statistically significant results in the non-Exos group may reflect reduced statistical power due to the smaller sample size, rather than a true absence of group differences. In fact, most symptom intensities differed by only ± 0.10 between the overall and non-Exos samples, suggesting the patterns are largely consistent across groups. An additional explanation for this is that the average age of Exos employees was nearly three years younger than that of non-Exos employees. Research suggests that hormone-related symptoms may be more prevalent and severe in younger females compared to their older peers during menstruation [6, 32]. These findings were consistent with other findings from the current study that show age related differences across MDQ subscale scores in which participants 22–29 years had higher scores across all MDQ subscale scores compared to their older peers.

The understanding of menstrual-related symptoms experienced during the intermenstrual phase is limited [33,34,35,36]. In the current study, twenty-one bleed-phase related disturbances, including cramps, were reported by at least 25% of participants during the intermenstrual phase. These disturbances could be due to ovulation pain, experienced by up to 40% of females, or premenstrual syndrome (PMS), which can appear anytime during the luteal phase [36, 37]. In a study of over 3,000 working women in Japan, Ozeki et al. [36] found that utilizing a PMS education checklist led to reduced intermenstrual MDQ scores [-8.44 points (95% CI: -14.73 to -2.15 points)], by follow-up, in participants with moderate-to-severe PMS symptoms who sought medical attention. The purpose of the PMS education checklist was to inform and create awareness of PMS. The checklist included eleven common PMS symptoms and advised participants to seek medical consultation if two or more symptoms were checked from the list. The reduction in MDQ scores among participants who sought medical attention was believed to have been attributed to the fact that they sought the assistance that resulted in the alleviation of their symptoms [36]. Most participants did not seek medical attention; therefore, the authors suggested that other lifestyle programs would be helpful for those uncomfortable seeking care [36].

Grandi et al. [35] investigated the impact of pelvic pain on quality of life in 300 patients and reported that intermenstrual pain was statistically associated with reduced quality of life and depressive mood. Our findings demonstrated that anxiety was the most prevalent (51.1%) and second most prevalent (47.5%) symptom during the remainder of the current cycle, in the overall and non-Exos samples, respectively. This is consistent with studies showing heightened anxiety in the luteal phase underscoring the impact of cyclical hormone fluctuations on female mental health [33, 38]. Research shows that mental health, specifically depression and anxiety, negatively impacts work-related productivity [39]. A systematic review found moderate evidence for the value of mental health interventions on work-related outcomes with the greatest support for programs intended to improve mental and physical health [40].

In the present study, participants reported a greater degree of negative perceptions across all work-related productivity measures during the pre-bleed and bleed phases and a greater degree of positive perceptions during the late follicular and early luteal phases. Ponzo et al. revealed that participants reported moderate-to-severe negative impact of their menstrual cycle on concentration at work (77.2%), efficiency (68.3%), energy levels (89.3%), relationships with coworkers (39.0%), interest in their own work (71.6%), and mood (86.9%) [13]. In comparison, this study showed lower reports of ‘somewhat to extremely’ negative impact on concentration (53.2% and 53.8%), efficiency (48.9% and 51.1%), energy (81.4% and 80.7%), relationships with coworkers (19.9% and 24.2%), levels of interest in work (42.4% and 44.8%), and mood at work (58.8% and 61.4%) during the bleed-phase in the overall and non-Exos samples, respectively. The percent differences between studies is likely attributed to the modifications made to these measures in this study to better understand the directionality of hormonal phase impact on work-related productivity. Despite these differences, the rank order of negatively impacted work-related productivity measures across the two studies is nearly identical. Findings from the current study also showed that perceptions of relationships with coworkers were more negative in Phase 4 compared to Phase 1. These findings are consistent with a study in 186 academic females in Egypt in which half of participants reported impairments in their relationships with their coworkers as a result of their premenstrual symptoms [41]. Coworker relationships may be disturbed due to premenstrual symptoms given that individuals spend a substantial portion of their waking hours interacting with their coworkers, either in person or remotely. Collectively, these findings support previous work that suggests that the menstrual cycle has a significant effect on work-related productivity [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

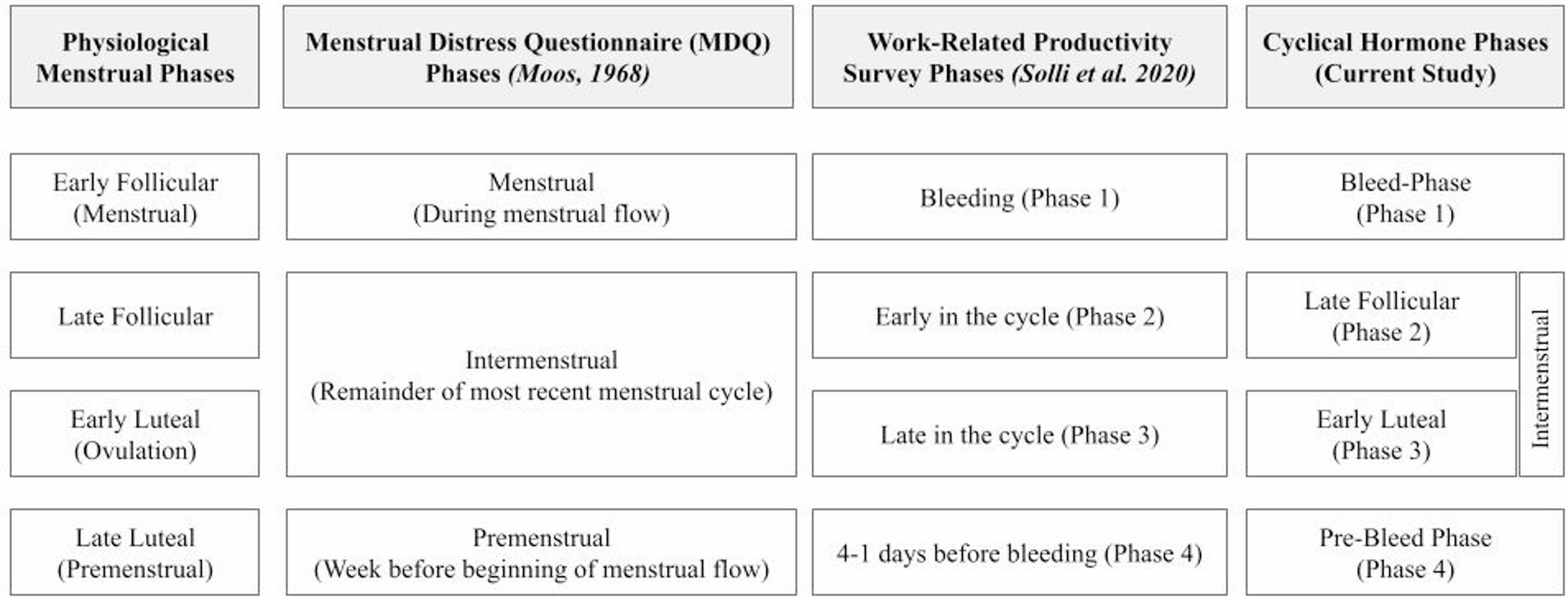

To our knowledge, this was the first study to assess the directionality of multiple work-related productivity areas across cyclical hormone phases and the relationship of self-reported hormonal-related symptoms to perceived work-related productivity. Generally, the symptom-related findings were largely consistent with theoretical expectations. For example, more intense bursts of energy were associated with greater perceptions of energy, independent of other covariates. Similarly, we found that many hormonal-related disturbances had significant inverse relationships with measures of perceived work-related productivity independent of other covariates. Participants were more likely to report more positive perceptions of work-related productivity during the late follicular and early luteal phases than the bleed-phase. However, more granularly, differences in distributions were observed in perceived efficiency, energy, and mood at work (p ≤ 0.05) between the late follicular and early luteal phases. Future work-related productivity research should include the intermenstrual phase and explore separating this phase into two independent phases (late follicular and early luteal).

Two variables, mood swings and contraceptive use, modeled with proportional odds in both the CLMM and Bayesian frameworks were significant only in the Bayesian models, likely due to the combined effects of the conservative Bonferroni adjustment and the Bayesian approach’s greater flexibility in estimating uncertainty. Other variables, including age, Exos employment, contraceptive use, and several MDQ subscale scores, modeled with non-proportional odds, were significant at one or both thresholds within the Bayesian framework but not in the CLMMs. For example, in both the relationships with coworkers and efficiency Bayesian models, Exos employment status was significantly associated with reporting higher odds of neutral perceptions relative to negative perceptions. These localized effects could be attributed to response bias such that Exos employees may have felt less comfortable reporting negatively about their ability to maintain relationships with their coworkers or perform efficiently since the study was conducted by their employer. However, given that Exos is a human performance company with an emphasis on well-being and performance, these findings may reflect contextual or cultural influences, such as a workplace environment that supports employees in ways that buffer against negative perceptions or promote more neutral evaluations of relationships and efficiency. Regardless of explanation, these findings reinforce the value of threshold-specific modeling in uncovering subtle associations that may otherwise go undetected.

Consistent with the literature, this study demonstrated that age, BMI, and heavy bleeding experience are significantly associated with hormonal-related symptom severity (p ≤ 0.05) [3, 6, 11, 32, 42–49]. However, after controlling for potential confounders, BMI and heavy bleeding experience were not significantly associated with perceptions of work-related productivity. Age had a significant inverse association across several perceptions of work-related productivity outcomes, including perceptions of concentration, relationships with coworkers, and efficiency using the frequentist CLMMs. The association between age and relationship with coworkers was maintained as a general effect in the Bayesian framework; however, the inverse relationship between age and concentration, and efficiency were significant only at the higher threshold, such that older participants had lower odds of reporting the most positive perceptions in these work-related areas of productivity. Age also showed a significant inverse relationship with energy, mood at work, and level of interest in work in the higher threshold of the Bayesian framework but was not significant in the CLMMs. To our knowledge, there are currently no studies that assess the relationship between older premenopausal females and perceptions of work-related concentration, energy, efficiency, mood, level of interest in work, or relationships with coworkers. However, many symptoms experienced during premenopause are consistent with perimenopausal symptoms; therefore, one possibility for these findings is that older females in this study may be experiencing early symptoms related to the perimenopausal transition that may be impacting their perceptions of work-related productivity in these areas [50]. For example, research has shown that as females age, specifically from midlife on, they experience hormonal shifts that impact energy, fatigue, concentration, and mood changes specifically as they approach and enter perimenopause [51–53]. Similarly, older females are more likely to practice work-family balance, experience age-related work discrimination, and intergenerational differences with their younger peers which may impact their ability to create and maintain relationships with their coworkers [54, 55].

Contraceptive use showed a significant inverse relationship with perceptions of concentration in both the frequentist cumulative link models and the Bayesian models, and efficiency and level of interest in work in the Bayesian models. Contraceptive use was only significant in the higher threshold of the Bayesian models such that participants that reported using contraceptives had higher odds of reporting more neutral perceptions of level of interest in work compared to positive perceptions. While there are individual studies that support the finding that contraceptive use is inversely associated with cognitive performance [56, 57], a recent systematic review by Gurvich et al. [58] has reported that the relationship between contraceptive use and cognitive performance is inconsistent. Also, in the present analysis, the variable contraceptive use consisted of various hormonal and non-hormonal contraceptives. As such, it is unclear which forms of contraceptives are driving these relationships. Collectively, these findings suggest that hormonal-related symptom severity may have a stronger association with perceptions of work-related productivity than demographics.

Variables such as decreased efficiency and multiple MDQ subscales including, MDQ concentration, MDQ arousal, and MDQ negative showed U-shaped patterns with perceptions of work-related productivity in Bayesian models such that higher symptom or MDQ subscale intensities were linked to both lower odds of neutral responses and higher odds of either negative or positive outcomes. This suggests that broader symptom clusters, consisting of numerous heterogeneous symptoms, may be associated with more polarized self-perceptions of work-related productivity outcomes. Alternatively, since the MDQ subscales consist of numerous individual symptoms, higher scores may be driven by varying symptoms across participants therefore it is unclear which symptoms are specifically driving these U-shaped relationships. However, consistent with the Yerkes-Dodson law that indicates a U-shaped relationship between psychological arousal and job performance, this may highlight a threshold of optimal versus excessive impact of symptom intensity on perceptions of work-related productivity [59]. This may also suggest that some symptoms may either enhance or disrupt functioning in an individual or reinforce the importance of relevant symptom clustering based on their relationship to a given work-related productivity outcome.

In general, the Bayesian models produced more conservative and stable estimates than the CLMMs, which showed signs of inflation in bootstrap resampling, likely due to sparse or imbalanced outcome categories in Phases 2 and 3. These Bayesian estimates offered a useful comparison point for understanding the strength and direction of phase effects, particularly where CLMM estimates may have overstated the association. Strong associations between Phases 2 and 3 and improved work-related productivity outcomes were consistently identified across both modeling approaches, reinforcing the robustness of this effect despite differences in model specification. Taken together, these findings highlight the value of combining frequentist and Bayesian methods in modeling ordinal data. The adjacent category structure, paired with PPO modeling, enabled detection of subtle or non-proportional effects that might otherwise remain hidden.

Similar to this study’s findings (13.2% and 13.4%) for the overall and non-Exos samples, respectively, a cohort of 32,749 Dutch women reported that 19.3% of participants reported missed days of work or school due to their menstrual cycle [18]. Despite the presence and severity of hormonal-related symptoms and the perceived impact on their productivity, most of our participants refrained from taking days off from work due to their menstrual cycle. In a study of 1,800 U.S. females, 5.4% of participants reported having access to menstrual-related benefits; the majority (75.6%) of participants who did not receive benefits expressed a desire [13]. These results are comparable to our sample, where 4.6% of all participants reported that their employer offered menstrual health benefits or wellness programs, with the majority reporting that menstrual health programming that addresses improving overall well-being would or might be something in which they would participate.

The current study uniquely sought to understand the receptivity to menstrual health programmatic content. Nearly all (95.7%; N = 369) participants showed interest in learning more about menstrual health, with 62% (N = 371) tracking their cycle ‘very often to always’. These percentages were consistent in the non-Exos sample. Despite nearly half feeling ‘very to extremely’ well equipped to manage their hormonal-related symptoms, the current sample expressed a great interest in content that would optimize their cycle and mitigate commonly reported hormonal-related symptoms like physical performance, energy management, sleep quality, and mood. Further, we sought to understand the receptivity to menstrual-programming delivery and found that participants were most comfortable receiving menstrual health programming from other females who were comparable in age or older peers.

Digital health apps and lifestyle programs, including physical activity and education-based content, have shown improvements in worker quality of life and productivity, and reduce the severity of some menstrual-related symptoms [13, 60, 61]. Established lifestyle programs can serve as a base for employer-sponsored menstrual health program development, aiming to optimize productivity during the late follicular and early luteal phases and minimize negative impacts during the pre-bleed and bleed phases. Other considerations should include stratifiers based on demographics, such as age, BMI, ethnicity, and race, or menstrual-related experiences and conditions such as heavy bleeding, PMS, or dysmenorrhea for more targeted alleviation of symptoms. However, programming against the presence and severity of specific or clusters of symptoms such as difficulty concentrating, decreased efficiency, mood swings, fatigue, and anxiety, may have a greater impact on work-related productivity.

This study’s strengths include a unique sample of U.S. working females, the evaluation of a wide range of affective and physical hormonal-related symptoms, and the inclusion of multiple work-related productivity measures assessed for bi-directional impact across four cyclical hormone fluctuation phases. Research investigating the lived menstrual cycle experience by working U.S. females is limited, as most related studies have primarily been conducted elsewhere [9, 13]. Environmental, geographical, and lifestyle exposures may have implications for menstrual cycle function and the risk of developing premenstrual disorders [62, 63]; therefore, research conducted outside of the United States may not best represent the U.S. female population [18, 22, 36, 64, 65].

Limitations of the current work include cross-sectional associations, the use of self-reported subjective data, modifications to Flo App’s Menstrual Cycle-Related Work Productivity Questionnaire [13] without pilot validation data, potential response bias, potential commercial interest, and the limited representation of racial diversity. Nearly 80% of the study participants were White. It is well established that racial disparities exist for reproductive health outcomes, menstrual care access, period poverty, and menstrual health issues [66–68]. It is also recognized that menstrual experiences differ by race and ethnicity, including the age of menarche, menstrual cycle length and variability, and in turn the risk of developing premenstrual risks during adulthood [69, 70]. Given the lack of racial diversity in this study, this limits the generalizability of these results and warrants the need for future studies to include a more diversified sample across races to more robustly evaluate these relationships. Given that 40% of participants were employees of the study funding organization this introduces the potential for response bias and therefore may limit the generalizability of the study findings. To ensure scientific integrity and minimize the potential for bias, participation in this study was completely voluntary, the study objectives were unrelated to employment positions and duties, and employment was in no way impacted based on someone’s election to participate in the study. Future research should aim to conduct large studies consisting of females across more diverse industries and organizations to confirm and expand upon these findings. Lastly, while every effort was made to ensure the objectivity and integrity of the research, it is important to acknowledge that, given the authors’ affiliation with the funding agency, either through employment or contract, this study may be subject to potential commercial influence. Readers should interpret the findings with consideration in mind.

Prospective longitudinal studies are needed to validate these findings. Future work should leverage objective work-related productivity measures and utilize cluster analyses to understand the personalized nature of hormonal-related symptoms. Due to survey tool limitations in the current study, the intermenstrual phase definition differed between the MDQ and the work-related productivity assessment. Future studies should consider parsing out the experience of MDQ symptoms by late follicular and early luteal phases. Lastly, although multiple comparison corrections were applied within each analytically distinct group, the study involved many comparisons across models and outcomes, and findings should be interpreted with an awareness of this broader multiplicity and validated in future research.