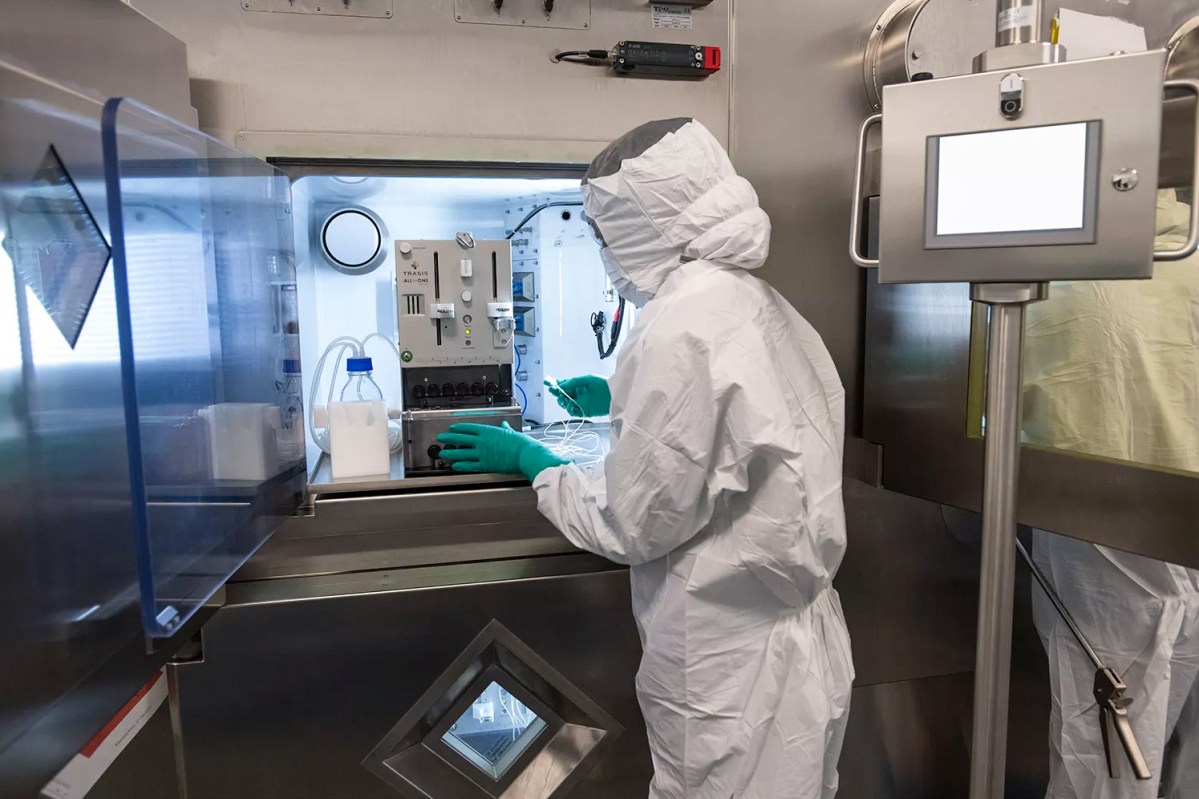

Novartis’s main radioligand lab had to be reinforced so 40 tonnes of lead could be installed to prevent radiation seeping into the rest of the building.

Novartis

Doctors and drug developers who first saw scans from a new targeted form of radiotherapy were amazed. For some patients in the clinical trial, Novartis’ radioligand therapy had – in just six months – completely cleared cancer that had spread around their bodies.

Michael Morris, an oncologist at New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, said it was “incredible” and “never seen before”. In the first trial he worked on, the scans were clear of cancer for about 9% of the participants. In the second trial, it was 21%.

External Content

“We can’t cure metastatic disease, but in most cases, treatment [also] really doesn’t impact how the disease appears on a scan,” he said. “We have something very different here.”

Novartis has been involved in developing cancer drugs for decades, but it became a pioneer in radioligand therapy after acquiring the technology in two deals. In 2017, it bought Advanced Accelerator Applications, which was founded by scientists from CERN, the European organisation for nuclear research. The following year it announced a $2.1 billion (CHF1.7 billion) deal for US biotech Endocyte.

Radiotherapy, which is used to treat about half of all cancer patients, is usually delivered from outside the body to kill cancerous cells, but healthy tissues are damaged in the process. Radioligand therapy is given intravenously as an infusion containing radioactive isotopes attached to a ligand. These are molecules that bind to receptors on cancer cells and allow a much more targeted dose of radiation to be delivered.

Logistical challenges

Lutathera, a radioligand therapy that Novartis acquired in the AAA deal, was first approved in 2017 as a treatment for some gastrointestinal cancers. The Swiss drugmaker received its first US approval for its prostate cancer drug Pluvicto in 2022 and has since expanded into treating patients with earlier stage disease.

More

More

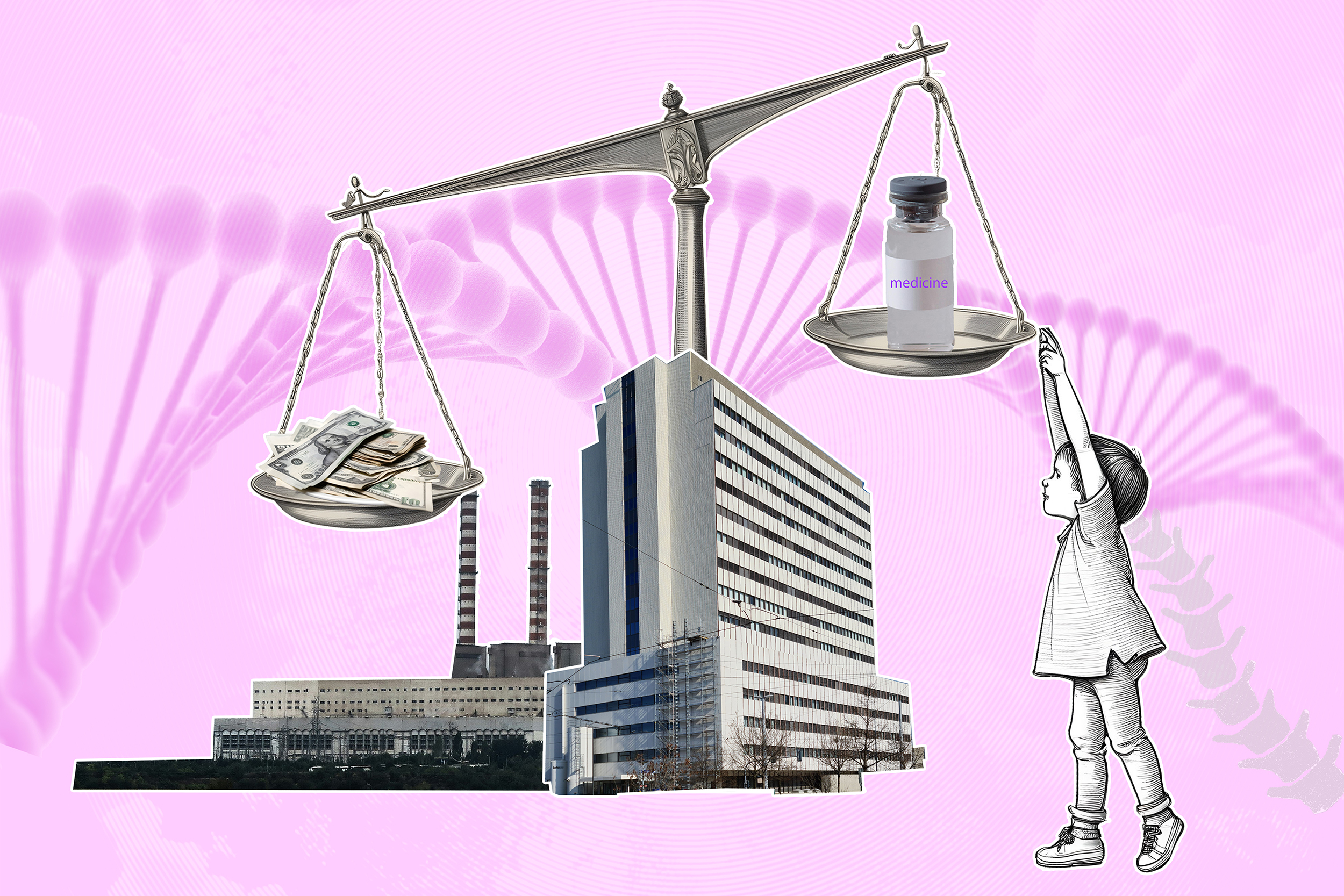

Why Switzerland pays more for cancer care than Sweden

In 2021, chief executive Vas Narasimhan estimated the market could be worth about $10 billion. Earlier this year, he told the Financial Times that if the therapy lives up to its promise, it could be a $25 billion to $30 billion market.

“We think there’s a whole set of targets that are unique that we think could only be targeted with radioligand therapy,” he said.

But the promising therapy comes with major logistical challenges. The radioisotopes must be made in a nuclear reactor, then the radioactive drug has to be safely manufactured, transported and delivered to patients.

Novartis has spent years working to overcome these hurdles. Yet other companies see the opportunities in the therapy and are racing to catch up. In 2023 and 2024, US drugmaker Lilly, UK pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, and French company Sanofi all bought start-ups developing radioligand therapies.

Philipp Holzer, executive director of radioligand therapy chemistry at Novartis, said companies were now popping up like “mushrooms”, and so were the suppliers of the isotopes. “There’s a market being created now,” he said.

Novartis has seven potential radioligand therapies in 15 clinical trials, with more in pre-clinical testing. It is exploring different isotopes, and therapies in combination, and expanding into other cancers including lung, breast, pancreatic and colon.

On the Novartis campus in Basel, the main radioligand lab had to be reinforced so 40 tonnes of lead could be installed to prevent radiation seeping into the rest of the building. All the scientists that work in it wear two dosimeters, including a mini one on their finger, to measure their radioactive exposure.

They are trying to find ways to make the therapy work for a wider range of cancers. This includes finding drugs that will bind to genetic mutations that are very common in tumours, but not elsewhere, to avoid irradiating healthy tissues.

“For every cancer type, it’ll be a unique solution,” said Narasimhan. “Very little in the human body is just like plug and play. You have to solve the challenges.”

More

More

Whatever happened to the world’s most expensive drug?

‘Future for cancer treatment’

Once new radioligand therapies are approved, the challenge is making them at scale. Novartis has purchased much of the supply of the radioactive isotope lutetium, so other companies are looking at alternatives such as actinium. Much of this isotope is sourced from Russia, so they are also looking for supplies elsewhere.

Once the radioactive material has been made, the company has only three to five days to create the drug and deliver it to the patient before the decay process starts to make it less effective. Each vial is made for an individual patient, tailored to their planned treatment date. Novartis has previously struggled to keep up with demand for Pluvicto, but 99.5% of injections are now administered on the planned day, it said.

Steffen Lang, president of operations at Novartis, said the isotope must be bound to the molecule that targets the cancer in the right concentration, and then checked for quality. “It’s not only quick, it needs to be right the first time.”

Then, a team works 24/7 to track GPS-tagged vials. Novartis is starting to use generative AI to help it anticipate logistical problems and select routes to hospitals. To get closer to hospitals and patients, it is expanding manufacturing plants from its current six in the US and Europe, adding more in China, Japan, and the US.

“Air traffic problems, severe weather conditions – we’ve seen it all,” Lang said.

There are further challenges when the radioligand therapy is given to patients: unlike with external radiotherapy, the radioactive material remains in the body, continuing to work after the dose is delivered. In some countries, including Germany and Japan, patients must remain isolated overnight in a radiation-proof hospital room. At the moment, there are few companies that can build this type of specialist facility.

Clinicians also need to be trained in how to care for these patients. In some countries, patients’ urine must be collected and stored for 70 days until the radioactive material in it has decayed.

Carla Bänziger, portfolio manager at asset manager Vontobel, a Novartis shareholder, said that despite the hurdles, targeted therapies like this are the “future for cancer treatment”.

She said this year is important for Novartis, partly because it received expanded approval for Pluvicto, doubling the potential patient population. Yet she believes it will still take ten to 15 years to build the ecosystem required for radioligand therapy to be mainstream.

Novartis has surmounted many of the problems, especially scaling production, creating a “high barrier to entry for other competitors”, she said.

Narasimhan agrees Novartis has an advantage. “When you enter this field by acquiring a biotech, which some of our peers have done, it gives you a start. But it’s a lot of work and investment to figure this out,” he said. “We have a five-year head start.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2025