Duodenal papillary lesions are difficult to detect and treat because of their special anatomical structure and location. Duodenal papillary lesions with malignant potential should be resected promptly, regardless of whether they are classified as adenomatous or cancerous lesions. Now the current treatment methods include surgery and endoscopic treatment. The perioperative mortality rate for conventional Whipple’s procedure is as high as 4–15%, and the recurrence rate after local resection is as high as 32% [10]. Currently, EP is considered a viable treatment option for benign ampullary neoplastic lesions and intramucosal carcinomas that have not invaded beyond the muscularis mucosa of the duodenum or exhibited pancreatobiliary duct infiltration.

Taking Biopsies from suspected lesions is essential to determine the histological categories for guiding appropriate treatment. Duodenal papillary lesions are predominantly adenomas or carcinomas, then inflammatory polyps, hyperplastic polyps, neuroendocrine tumors, misshapen tumors, and duodenal adenomatous hyperplasia are also seen in specimens. In our cohort, the pathologic types of 58 duodenal papillary lesions included negative for neoplasia (pyloric gland ectasia) in 2 cases (3.4%), neuroendocrine tumor in 1 case (1.7%), LGIN in 29 cases (50%), HGIN in 9 cases (15.5%) and carcinoma in 17 cases (29.3%). In the study, the rate of pathological difference between biopsy and excision specimens was about 50%. Gastric heterotopia of the duodenum is a congenital developmental anomaly with potential for malignant transformation, though the actual occurrence is rare and it is generally regarded as a benign lesion [16, 17]. Intraepithelial neoplasia is considered to be a precursor of carcinogenesis, among which high-grade atypical hyperplasia is considered a risk factor for malignancy. Therefore, it is very important to distinguish between low-grade and high-grade atypical hyperplasia. In this study, lesions with histologically diagnosed as negative for neoplasia and LGIN after resection were classified as benign lesions, while HGIN and carcinoma were classified as malignant lesions(excluding patients with postoperative pathology of neuroendocrine tumors). Duodenal papillary lesions were predominantly found in middle-aged and elderly patients, with an average age of 61.26 ± 9.82 years, but no significant difference was observed in gender.

Biliary tract disease is considered to be associated with the development of ampullary cancer. Gallstones were found to be associated with a three-fold increased risk of duodenal papillary lesions in a meta-analysis [18]. Bile acids can cause DNA damage through oxidative stress and production of reactive oxygen species. Moreover, continuous flow of bile acids in the duodenum and structural changes in the intestinal flora after cholecystectomy increase the incidence of intestinal cancer [19, 20]. A retrospective analysis conducted by Piera et al. [21] included 669 patients, which was consistent with previous studies that cholecystectomy was a significant risk factor for duodenal papillary lesions. In our study, 48.3% (28/57) of patients with duodenal papillopathy had biliary tract disease including chronic cholecystitis, gallbladder stones, choledocholithiasis etc., there was no significant difference in which between benign and malignant papillary lesions (P = 0.292). The dilation of biliary and pancreatic duct on radiologic imaging (p = 0.003) was associated with the histological upgrades to HGIN or duodenal papillary carcinoma from LGIN, which was also a statistically significant difference between benign and malignant papillary lesions (P = 0.001), suggesting a risk factor for malignancy in ampullary adenomas.

ANLs involve the major papilla, originating in intestinal-type mucosa, and following the sequence from adenoma-to-carcinoma, which was similar to the development of colorectal cancer [7, 22]. It is a heterogeneous disease, implying that the occult foci of malignant tumors may not be adequately represented in endoscopic biopsy specimens. Moreover, malignant cells may exhibit horizontal spread along the level of the basement membrane. If the tissue obtained via endoscopic biopsy is insufficient, the leisons may be misdiagnosed as LGINs or HGINs. So it is difficult to distinguish between adenoma and carcinoma without complete removal of the lesion. Therefore, current literature recommends obtaining four or more biopsy specimens while avoiding the orifice region to improve diagnostic accuracy and minimize complications associated with endoscopic biopsy [23]. Although EUS-guided tissue sampling is anticipated to demonstrate superior diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity, its clinical application remains limited due to restricted equipment availability in many centers [10].It is reported that the rate of missed diagnosis of duodenal papillary adenocarcinoma is high, about 20–30% [8]. Similarly, we found that 29.8% (17/57) of patients were diagnosed with cancer after surgery. Among the 18 lesions diagnosed as HGIN by biopsy, 13 (72.2%) were upgraded to carcinoma after resection, which was associated with gender (p = 0.008) and lesion size (p = 0.035) in histological upgrade. 10 patients underwent traditional treatments due to that large lesions were more likely to develop histopathologic upgrade. 8 patients chose EP, 2 of which (2/8, 25%) had mucosal cancer, while 1 of which were submucosal invasive, treated with additional surgery. The average diameter of benign lesions was (1.29 ± 0.72) cm and that of malignant group was (1.74 ± 0.48) cm, the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.008). Logistic regression analysis indicated that lesion size(> 1.25 cm, OR 3.566) was a significant predictor of malignancy in ampullary adenomas. Furthermore, several studies revealed that large lesions (> 20 mm) might be associated with depth of tumor invasion and local recurrence after resection [24, 25]. The discrepancy of size in our study may have arisen because our malignant lesion subgroup included cases of HGIN.

It has been reported that in patients with ANLs aged over 65 years, the presence of clinical symptoms, villous components, HGIN by biopsy, enlarged duodenal papilla and duct dilatation on radiologic imaging is associated with an increased risk of histological progression [26]. Another study indicated that the older age and unclear with the surrounding mucosa were independent predictors of malignancy in ampullary adenomas [27]. According to the VS classification system, the result was an absent MV pattern plus irregular MS pattern with a demarcation line, leading to a diagnosis of cancer. However, the enlargement of duodenal papilla and clear boundary were not associated with histologic upgrade after resection in our study.

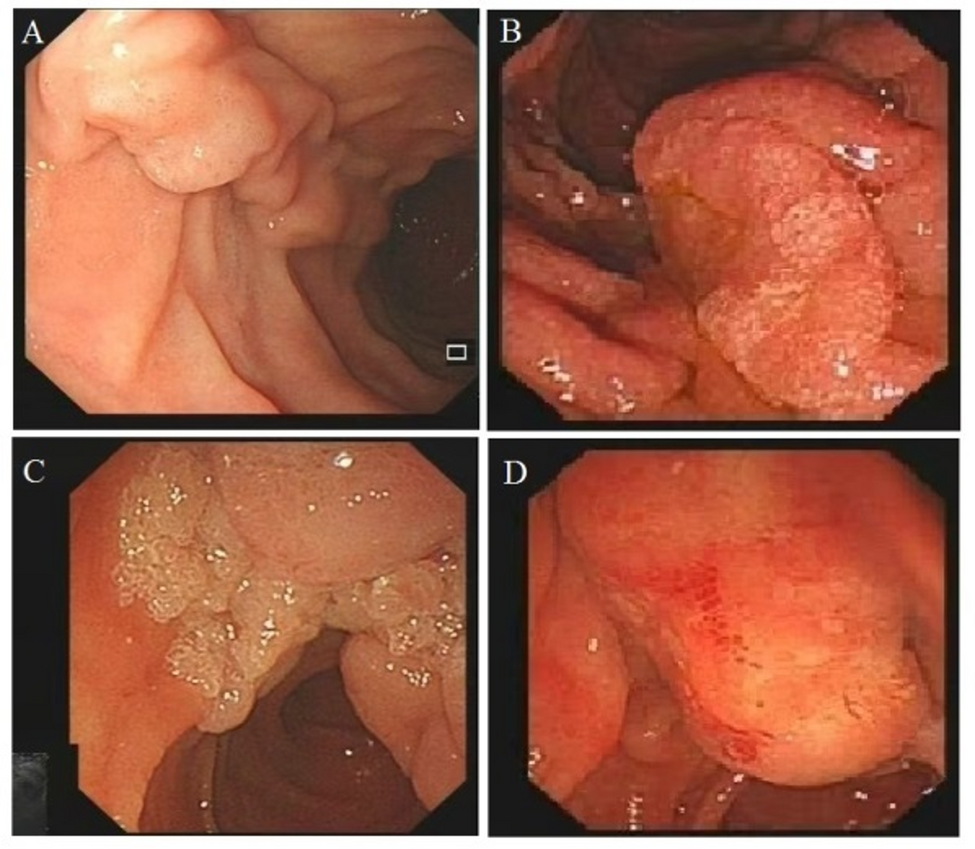

Uchiyama et al. [28] had established a classification system to distinguish benign and malignant ampullary tumors with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI) based on the vessel patterns and surface structures of the ampullary lesions. WOS has been confirmed by histopathology and immunohistochemistry to be the accumulation of lipid droplets in the mucosa by histopathology and immunohistochemistry [29,30,31,32]. Kawasaki et al. [33] reported that the distribution of lipid droplets observed in colorectal tumors may be closely related to the visibility of WOS under M-NBI colonoscopy, as well as with the histological grade and depth of tumor invasion. However, histological upgrade was not associated with villous-like changes and the presence of WOS of the surface structure.

The benign characteristics of ANLs under white-light endoscopy typically include a regular surface and edge, soft consistency, and mobility. In contrast, features such as superficial erosions, ulceration, friability, hard consistency, firmness, and spontaneous bleeding are generally associated with malignancy [1]. In our study, the lesions were mainly elevated in appearance, but it was warned that the depressed lesions was associated with an increased histologic risk of deep invasion.

A few years ago, EP had not achieved widespread adoption in municipal tertiary hospitals across China, with generally low patient acceptance of this technique. Recent advances in imaging and therapeutic techniques have established EP as a first-line treatment for non-invasive lesions, with multiple studies demonstrating its reliable safety and efficacy profile [12]. In our study, following comprehensive preoperative evaluation of risks and benefits, and after integrated consideration of complication risks, life expectancy, and postoperative follow-up capacity, among 40 lesions histologically diagnosed as indefinite for neoplasia and LGIN, or indeterminate pathology, five patients ultimately opted for surgical resection due to strong personal preference for operative intervention. the postoperative identification of LGIN in two surgically treated cases would likely be considered regrettable by current therapeutic standards. However, EP remains technically demanding, requiring substantial endoscopic expertise that limits its universal application. Strict adherence to EP indications and a comprehensive preoperative evaluation of technical feasibility can not only improve clinical and economic outcomes by reducing hospital stays and enhancing patient comfort, but also facilitate the rational utilization of interventional endoscopy resources.The final analysis included 58 cases, meeting the predetermined sample size requirement (margin of error E < 15%). The observed difference rate was 50%, with an actual 95% confidence interval (CI) of 25.8% (37.1–62.9%), confirming statistical adequacy. However, as a single-center study, the generalizability of findings may be limited due to potential selection bias and institutional-specific practices. In our study, for the categorical variables of color and ductal dilation, where certain classification levels contained extremely small sample sizes, the resultant data sparsity made the modeling statistically unreliable, which reflects an inherent limitation of data collection rather than indicating methodological flaws in statistical analysis, suggesting that future large-sample studies are warranted for validation. Prior to further validation, it is recommended to consider duct dilatation/color as exploratory features, which should be systematically assessed in conjunction with EUS and tumor markers (e.g., CA19-9).

This study has some limitations. Firstly, being a single-center retrospective study, there is a potential for selection bias and many endoscopic pictures are not standard enough. X2and student’s t-test are fundamentally univariate analyses, which are unable to account for or eliminate confounding bias. The study population consisted solely of patients, without a corresponding healthy control group for comparison. Therefore, the test indicators deviated from the normal values. Due to the limited sample accuracy, when there are very few samples at a certain classification level, it is equivalent to the absence of data, and its independent effect cannot be reliably estimated. So, when the results of a single variable suggest a strong correlation, a larger sample is even more necessary for verification. Secondly, the sample size of biopsy-diagnosed HGINs included in this study was relatively limited. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of HGIN lesions initially diagnosed by biopsy were subsequently reclassified as cancer following surgical resection. Thirdly, variations in magnification levels might have influenced the outcomes of the M-NBI study. Thourthly, this study failed to fully demonstrate the diagnostic advantages of EUS in the evaluation of duodenal lesions, highlighting the need for more comprehensive utilization of EUS in future clinical practice to optimize lesion characterization and staging accuracy. Finally, the absence of a standardized biopsy protocol, including defined criteria for sampling quantity and targeted anatomical locations, may lead to inaccurate pathological assessment and potentially affect the accuracy of diagnosis. In addition, this small-sample study may be subject to systematic biases, and its findings may not be generalizable to the broader population. Therefore, it is necessary to validate the conclusions in multiple centers with large samples.