More than four decades ago, a young electronic instrument developer at Casio programmed a preset rhythm pattern into an inexpensive keyboard. This was discovered by reggae artists half a world away, and Okuda Hiroko’s “Sleng Teng riddim” spawned countless Jamaican hits. We sat down with Okuda, who retires from Casio this year, to talk about her life with music and her future.

A Pioneering Career of Firsts

In 1980, a young woman who loved Jamaican music and graduated from music college with a thesis on reggae joined Casio Computer as a developer. The very first instrument she worked on helped usher in a digital revolution in Jamaican music. She later described the experience as “like putting a love letter in a bottle and throwing it into the sea, then having it wash up on the other side of the ocean and find its way into the hands of your beloved.” When Okuda Hiroko spoke to Nippon.com in early 2022, it was the first time she had gone on the record about the life-changing impact of this event so early in her career.

On July 20 this year, Okuda retired from Casio after nearly 45 years. She joined when Casio was branching out from calculators and digital watches to make its first electronic musical instruments. She was the first female developer in the company’s history, and the first employee to have graduated from music college. Immediately after initial training, she was put to work on product development. One of her first jobs was to work on preset rhythm patterns for the Casiotone MT-40 keyboard.

The Casiotone MT-40. (© Nippon.com)

A Casio Preset Becomes a “Monster Riddim” of Reggae

Jamaican musician Wayne Smith was among many around the world to acquire an MT-40. In 1985, he released the track Under Mi Sleng Teng, which became a huge hit. Underlying the song was the preprogrammed “rock” setting that Okuda had created soon after joining Casio.

“Riddim” patterns, generally consisting of a drum pattern and bassline, are an important foundational element of modern reggae and related styles. These riddims are often recycled, and a popular bassline may be used by other musicians to create new songs and variations on the same basic pattern. Okuda’s Casio pattern became known as the “Sleng Teng” riddim after Wayne Smith’s record. It went on to become the driving force behind hit after hit, and helped launch the digital age in reggae, at a time when making a record required live musicians. To date, more than 450 different tracks have been made using the Sleng Teng riddim, which has become known as one of the “monster riddims” of Jamaican music.

Although it was common knowledge among Jamaican music aficionados that the Sleng Teng riddim was originally a preset on the MT-40, and that it had originated with a young woman in faraway Japan, Okuda never showed her face in the press or consented to be interviewed about her work. Then, three and a half years ago, as she became aware that her time at Casio was coming to an end, she agreed to be interviewed for Nippon.com. The resulting article appeared in all eight of the website’s languages, creating a stir among music fans around the world.

Feeling Like a Celebrity

We asked what sort of response Okuda had when the article appeared.

“At first, I just watched as the story started to get picked up on social media here in Japan. Then the next thing I knew, it was the top story on Yahoo Topics. I started to get requests for interviews on radio. But the biggest surprise was when I appeared on the front page of a national newspaper. They’d done an interview, and I knew the article was due to appear, but when I popped to the convenience store to pick up a copy, there I was on the front page! I was so surprised I bought an extra copy to send to my parents.”

Okuda says the international response was also surprising. “After the article appeared in English, I was approached by various international media including the BBC and Associated Press, and I was interviewed online for Jamaican TV. Every time one of these stories was published, there was a new flood of messages into my inbox.”

Much of this took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Okuda recalls that in the isolation of those days, it was difficult to get a real sense of how well known she was becoming. “In June 2022, after your article appeared, I was invited to give a talk at the Casio booth at NAMM, a trade fair for musical instruments held every year in Anaheim, California.

“Since I was due to be interviewed for local media, I took an MT-40 along so that they could see the real thing and get photos. Well, when I left the booth holding the instrument, I was suddenly surrounded. People came up to me saying, ‘I know who you are.’ Everyone was saying how cool the instrument was and asking to take selfies. It was amazing. Partly, I’m sure, it was because there were so many people from the music industry there. But even so—it did make me feel for the first time that maybe I had become a kind of celebrity!”

For Okuda personally, she recalls, this wasn’t fame she was ready to embrace. “I shuffled out of the limelight again as quickly as possible. I didn’t want to distract from our new products by creating a fuss about an instrument that had gone on sale more than forty years ago!”

Still, she says, to this day when she attends trade fairs and similar events, people from other Japanese manufacturers have come up to say, “You’re Okuda-san, right? Let me shake your hand.” She laughs: “I would never have imagined in my life that the day would come when strangers would approach me to shake my hand or ask me to sign something.”

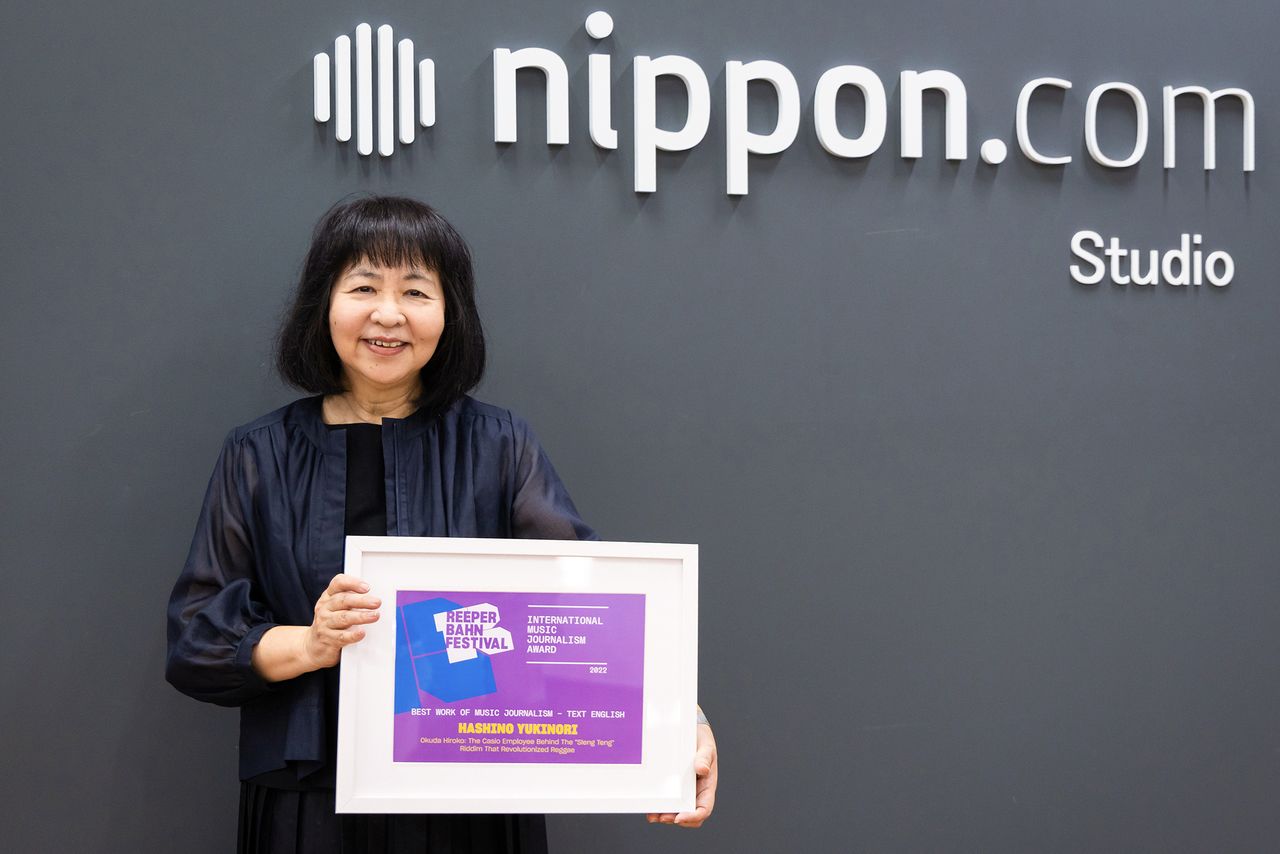

Okuda with the International Music Journalism Award 2022, awarded for the Nippon.com article about her part in the Sleng Teng phenomenon. (© Nippon.com)

Products That Tell Persuasive Stories

Looking back on her career as a developer at Casio, Okuda notes that her main memory is of being really busy, from start to finish. “I was lucky to be able to work on products that were in my own area of interest throughout my career, though,” she adds. “I was very happy. As a developer, your job is to create something new through a process of addition. I think the work suited me—in many jobs, you’re required to make things perfect, and if you make a mistake that immediately subtracts from the whole.”

Coming from a musical background, she agrees that in a sense this is something like composing music—creating something out of nothing. In the case of electronic instruments in particular, she says, “You’re bringing your own sensibility to digital technology. That’s what makes it fun and is also probably a large part of the reason why I was able to spend so long as a developer. If you’re an engineer without that sensibility, it can be a bit of a struggle if your area of specialization becomes obsolete and is no longer in demand.”

The subject turns to artificial intelligence and whether it will have an impact on the field of electronic instruments. Okuda believes that the electronic instruments of the future will primarily feature piano-style keyboards, without so many of the buttons and switches seen on today’s models. “Some modern electronic keyboards already have as many as 500 or 700 different sound settings to choose from—sounds you would never normally encounter and would never find anywhere else,” she notes. “The range of options already exceeds what a person could realistically choose from.”

If you let AI hear what you want to play, she explains, it will immediately adjust the sound settings to more or less exactly what you need. But it still requires input, and the joy of playing music never changes, so she remains confident there will always be a demand for keyboards with a good touch.

For tools used to create art, she believes, it will always be important to appeal to human sensibility. “I think part of the reason why my story resonated with people was that I worked on creating musical content as well as just the hardware. There are plenty of outstanding electronic instruments and many gifted technicians and engineers, but perhaps not so many with good musical content as well.

“People in Jamaica discovered the preset rhythm I created for the MT-40 and used it to make one great song after another. This product, which sold for just 35,000 yen, made it easier for people to make and record their own songs, and also led to digitalization, which injected new life and energy into reggae. It’s stories like this that made the MT-40 a favorite with so many, and also earned me my moment in the spotlight.”

Perhaps, thinks Okuda, it is not as easy to develop revolutionary products as it used to be, now that so much work has already been done. “Maybe really outstanding content and stories have been a bit lacking from Japanese products in recent years. Partly, of course, I just got lucky. I am really grateful to Jamaican people and thrilled that I was able to give something back to the reggae music I love so much.”

In the Nippon.com studio. (© Nippon.com)

Hopes for the Future

Is there anything Okuda regrets about her career as a developer? Her answer is a surprising one: “I was always so busy that I have still never managed to get to Jamaica! It’s been so long now, part of me feels it would make a better story if I never visited and only ever admired the country from a distance.”

Okuda has come up on retirement age at Casio and is considering her next moves. She doesn’t really know what comes next, she says, but “I still have loads of ideas as a developer. Some are for things that would be difficult to develop commercially at a company like Casio, where your products have to target a global audience, but might be easier with a small-scale team. So I’m hoping I’ll be able to find people who will help me get some of those ideas out of my head and into development.”

It seems likely that music will be a part of that future. As Okuda enthuses: “Music is such a wonderful thing. I’ve had experiences that I will always treasure thanks to so many passionate fans all around the world. It was thanks to the power of music that the article about my role in the Sleng Teng story won a music journalism prize. And music can bring us solace and comfort in difficult times.”

Even more than acoustic instruments, she says, electronic instruments can find a place in the lives of people who may not be virtuoso performers, bringing the pleasure of playing music to more people. “The Music Tapestry project, which I worked on right to the end of my time at Casio, offers another new way to enjoy music, by spinning musical sounds into artistic pictures. I definitely want to build on my experience at Casio and continue to contribute to music in one way or another in the future.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Okuda Hiroko during a visit to the Nippon.com office to announce her retirement from Casio. © Nippon.com.)