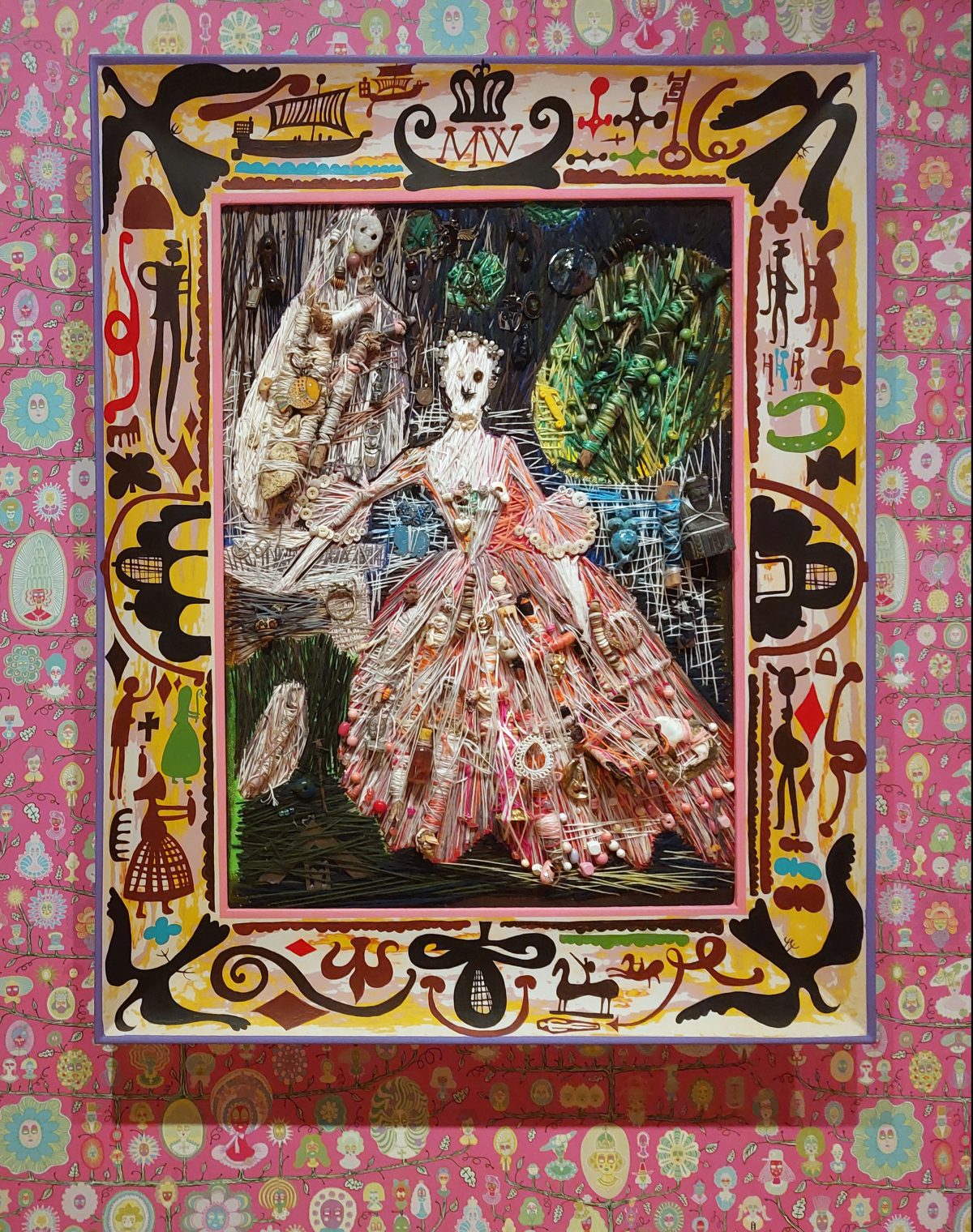

LONDON — The Wallace Collection is famous for its trove of Rococo art, such as Fragonard’s pastel depiction of indulgent flirtation “The Swing” (1767–68), in which a woman with a voluminous skirt kicks a pink slipper into the air with coquettish abandon, closely watched by two male suitors. In his solo exhibition, Grayson Perry responds to these holdings, offering a fever-dream take on Fragonard’s painting in a tapestry entitled “Fascist Swing” (2024). Here, pastels give way to psychedelically bright colors, while the woman’s smiling expression is contorted into a mask of horror. The laughing suitors are also absent — Perry’s protagonist is alone in her mental disintegration. The work depicts a delusion of excess and grandeur much like Fragonard’s, but with a much darker, more frightening tone.

“Fascist Swing” depicts Perry’s alter ego Shirley Smith, dreamed up for this exhibition as a way to explore both the Wallace Collection and his ideas around gender, class, and mental illness. Smith, Perry tells us, is a working-class Londoner whose mental illness pushed her into “delusions of grandeur,” as the exhibition’s title puts it, leading to a prolonged psychotic breakdown in which she came to believe she was a member of the aristocracy and the rightful heir to Hertford House, the home of the Collection. Smith is based in part on real-life so-called outsider artists who suffered from mental health challenges and delusions, such as Aloïse Corbaz (1886–1964) and Madge Gill (1882–61) — some of whose fascinating works are included at the beginning of the exhibition.

Visitors unprepared for Perry’s gesamtkunstwerk approach to this exhibition may be puzzled by this opening room, where the boundary between truth and fiction is bafflingly but effectively blurred. Fictionalized “archival” photographs of and letters by Smith sit beside real documentation of Gill’s activities at the Wallace Collection in the 1940s, with false dates attributed to the former but not the latter, for instance. Unusually, the audio guide is key to entering Perry/Smith’s world; tracks are alternately narrated by Perry and Smith, making for an immersive experience — although it is a shame that Smith is given a caricatured Cockney accent, which creates a lazily stereotyped image of working-class identity.

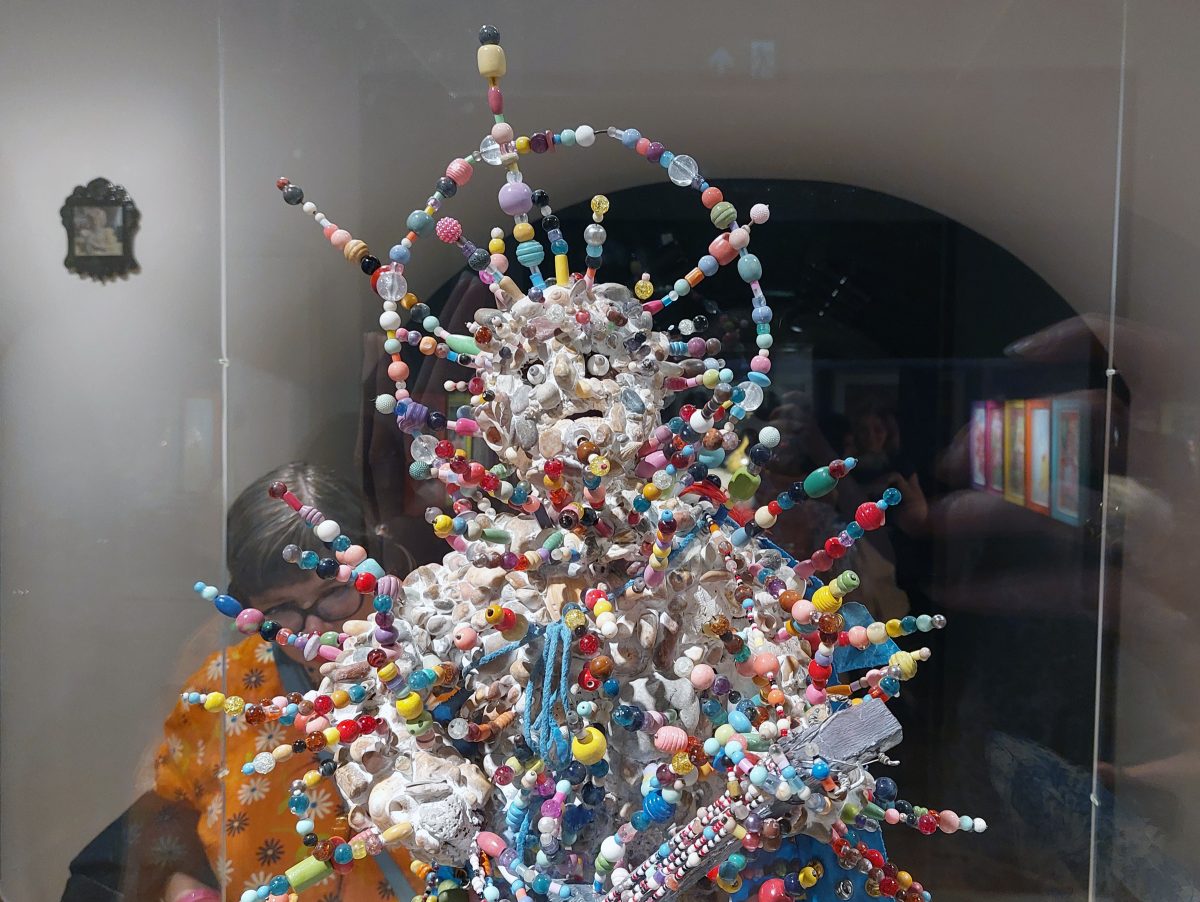

The exhibition loosely follows Smith’s life, ending in a quasi-recreation of the bedroom in which she spent her final days. There are some beautiful objects in here, including a cabinet decorated with portraits of women from the Wallace Collection. There is also a piece called “Hospital Queen” (2024), a hand-beaded self-portrait Smith supposedly made during a stay in a mental hospital. This perhaps alludes to our somewhat morbid fascination with such objects. But even though Perry has struggled with issues around mental health, his treatment feels a bit flippant.

Similarly, in “A Tree in a Landscape” (2024), Perry creates a family tree using portrait miniatures from the museum’s collection, labeling each one with a different mental health diagnosis. The caption notes, “We all exhibit some traits that could be pathologized.” Do we? Perry’s analysis feels glib; here, as in his treatment of Smith’s psychosis, he fails to engage with the realities of serious mental illness.

This is but one instance of a recurring lack of nuance in some of Perry’s engagements with complex issues. It is evident that he thinks deeply — but not always about the right things in the right places. For instance, “Man of Stories” (2024), a central piece in the exhibition, is a truly (and deliberately) hideous beaded sculpture of a bard-like figure, inspired by “the expert storytellers of the Luba people in central Africa,” according to Perry’s caption. It is not explained why Perry was inspired by this particular culture, or whether the Luba people have any connection to objects held in the Wallace Collection. The caption continues: “One of my ongoing concerns is over-intellectualism in Western culture, so I was fascinated by the idea of a travelling bard.” Is the implication that he is ascribing a desirable non-intellectualism to central African culture? This speaks to me, at best, of a failure to allow viewers to engage with the figure at an intellectual level, and at worst, of exoticism.

In general, Perry is interesting because instead of asking vague questions about what it means to be a human in a universal sense, he queries what it means to be a human specifically living within the intersections of class and gender in British society. When I visited on a Saturday afternoon, the exhibition was packed with people; Perry is undoubtedly popular. His colorful, down-to-earth approach evidently holds a widespread appeal, and that in itself is valuable, drawing visitors into a new engagement with conceptions of gender and class, as well as questions of how we respond to historic collections. However, it is a damaging falsity to assume the public can’t be engaged by a more nuanced approach to these issues. This is where this exhibition — in its ugliness, brashness, and occasional moments of insensitivity — falls short.

Grayson Perry: Delusions of Grandeur continues at the Wallace Collection (Hertford House, Manchester Square, London) through October 26. The exhibition was curated by the artist.