Subscribe now for full access and no adverts

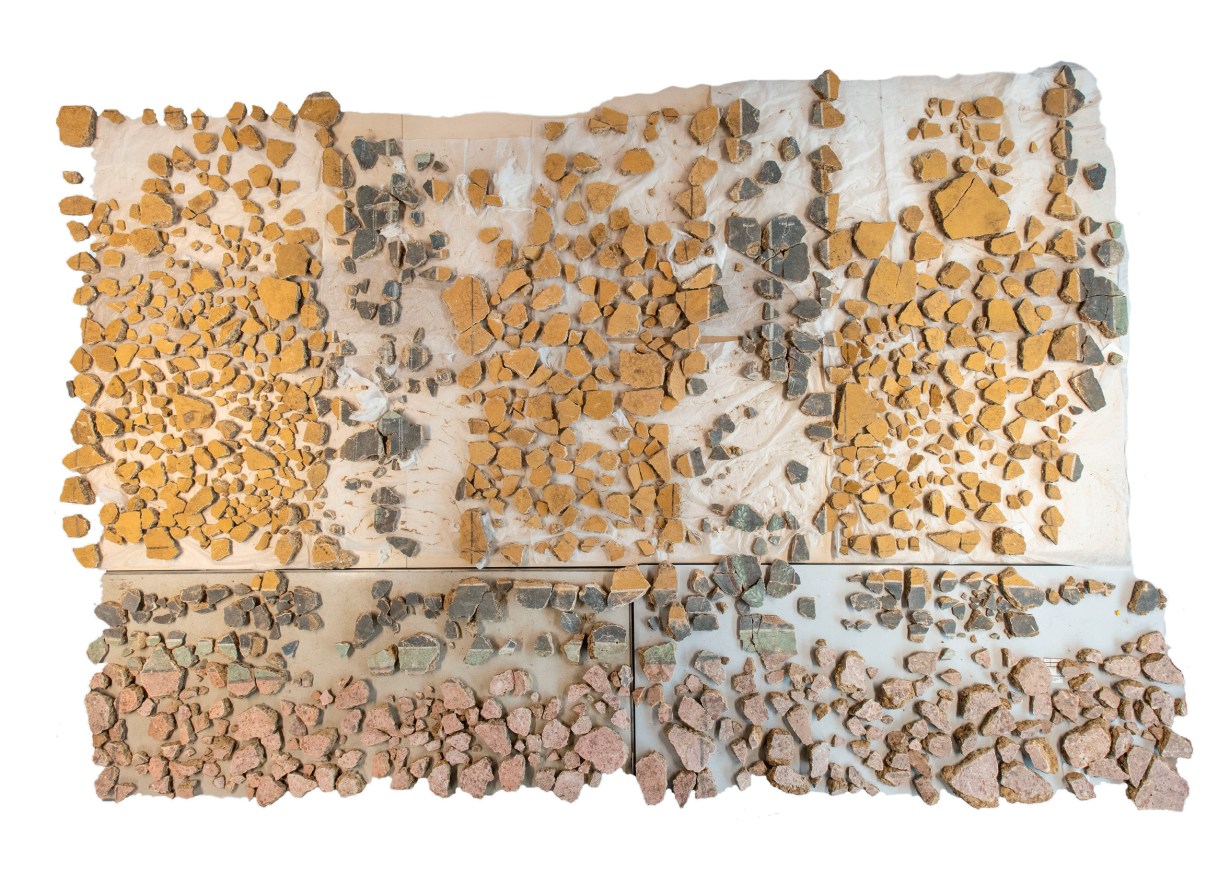

The table before me was awash with colour: a shattered sea of pink, yellow, green, and black formed from large chunks and smaller fragments of plaster that had been painstakingly pieced back together to create a coherent whole. Two thousand years ago, these still-vibrant remains would have formed part of a fresco adorning one of the walls of a high-status building in Roman Southwark, clearly signalling the wealth and taste of its owner to anyone who ventured inside. They also represent just a portion of a major archaeological discovery that was unveiled earlier this year: one of the largest assemblages of painted wall plaster that has ever been found from Roman London.

This colourful collection, comprising thousands of individual fragments, was discovered during excavations by MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) on the site of The Liberty, near London Bridge in Southwark. Between 2021 and 2024, these investigations (undertaken on behalf of Landsec, Transport for London, and Southwark Council ahead of the creation of a new cultural quarter) uncovered illuminating insights into the lives and livelihoods of people who lived south of the Thames during the Roman period, including elaborate mosaics and a grand mausoleum that formed part of a large later cemetery (see CA 386 and 402).

Located across the river from the bustle of Londinium, this was a wealthy suburb whose residents built opulent houses along the waterfront. Excavations in the 1980s and in 2005 had already revealed the remains of some of these structures, including the northern part of a large building complex that was interpreted as a possible mansio (a residence for important travellers on official business) or a particularly luxurious private dwelling. It was constructed early in Roman London’s history, before AD 120, and although its owners had evidently lavished money on its design, commissioning mosaic floors and elaborately painted walls, MOLA’s more recent work on the site has revealed that the building was relatively short-lived. It was demolished sometime before AD 200, during which time the crumbled remains of its fine frescos were consigned to a large pit, where they would remain until their rediscovery almost 2,000 years later.

Colourful clues

Over 120 boxes of plaster fragments – enough to cover an estimated 20 internal walls – were recovered from the site, and the challenge of piecing them back together has been taken up by Han Li, MOLA’s Senior Building Material Specialist. Drawing on parallels from across Europe and insights from other experts – including colleagues at the MOLA finds team, his predecessor Dr Ian Betts, and other scholars including those at the British School at Rome – for months Han has been painstakingly matching edges, images, and even common patterns of dirt or residue on some of the pieces’ surfaces in order to reconstruct long-vanished decorative schemes and tease out what they can tell us about the tastes and cultural connections of some of Roman London’s wealthier inhabitants.

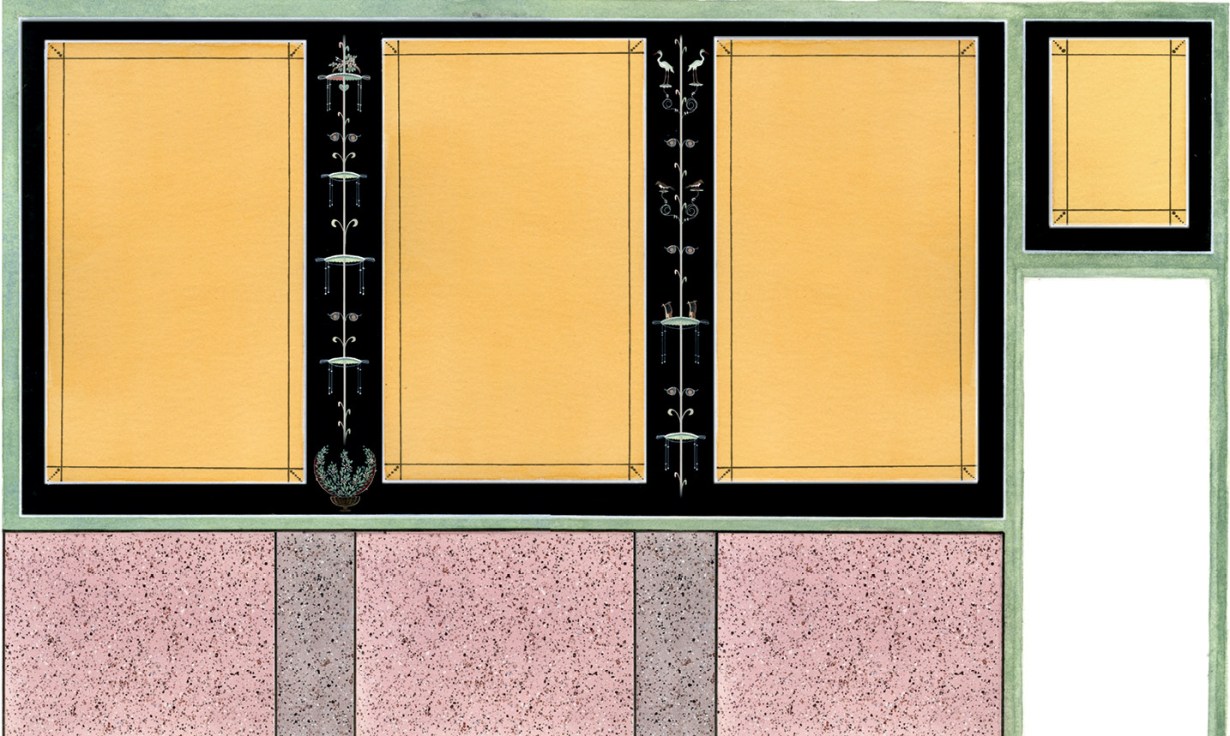

It was Han who was my guide as I gazed at the colourful fragments that had been carefully arranged on a table at MOLA’s headquarters in Hackney. Reconstructing a single, brightly painted wall, they formed a fairly typical design known from sites across the Roman Empire, with repeating panels in a block colour set above a dado painted to look like expensive imported stone. There would have also been a decorative frieze along the top, Han added, but these rarely survive well enough to be reconstructed – as this section of the plasterwork falls from the greatest height when its underlying wall is demolished, it tends to shatter into very tiny pieces, while lower elements generally form larger chunks that are more easily interpreted and reunited.

In this example, the wall had been painted a bright sunflower yellow – a shade that is not in itself unusual in Roman frescos, Han said, though it does not appear to have been a common choice for the main repeating panels. Red seems to have been the more popular colour, though examples of yellow panels are known from other sites including Fishbourne Palace in West Sussex, Silver Street in Lincoln, and Xanten in Germany – and, Han added, there may be others boxed up in archives that are still waiting to be reconstructed. Like those at Xanten, the Southwark structure’s panels were divided with black intervals edged in green and, by closely examining areas where the pigment has flaked away, we can tell that the whole wall was initially painted yellow before the bands were added, rather than setting these out first and then trying to ‘colour inside the lines’.

The black intervals themselves offered even more intricate details, providing the background for delicate images of fruit, flowers, and foliage; lyres; and white birds with long necks and red beaks, possibly some kind of wader, crane, or stork. Many of these had been found in multiple fragments, which Han had carefully fitted back together, and another recurring motif showed a tall candelabrum growing variously out of a slender stem or a bushy vertical spray of leaves and flowers. Thought to have originated in Pompeii, candelabrum imagery was evidently a popular theme as it is found in localised styles across the Roman Empire including at Xanten and Cologne in Germany, Lyon in France, and sites in Britain including Boxmoor in Hertfordshire and Leicester – demonstrating how far artistic ideas and interior design fashions can spread.

Artful designs

To modern eyes, these decorative schemes might appear rather ‘busy’, even gaudy – but to the people who commissioned them they would have represented the epitome of taste and style, and a highly visible statement of their status within Roman society. Some of the individual pigments would have also been chosen to impress; contemporary visitors would not have missed the use of Egyptian blue, a vivid synthetic shade that was much more costly than natural earth colours. Perhaps because of this expense it had been used only sparingly on the frescos that Han showed me (picking out details of the lyres and candelabra, as well as a face with a wig, probably representing a theatrical mask, from another wall) but its presence, however small, would have surely been a source of great pride.

There were also more budget-friendly methods at work; beneath the yellow panel, the same wall’s dado had been skilfully painted to look like speckled pink marble, fooling the eye into imagining exotic (and expensive) stone veneers. On an adjacent table, a group of fragments painted in the same way but using a slightly different shade of pink suggested that at least one other room had been decorated in a similar way, while a third set spoke of something rather more high-end. These last fragments were painted with a darker pigment imitating red Egyptian porphyry, a highly prized crystal-flecked volcanic stone. Adding to this prestigious picture, Han noted, the white speckles of this ‘stone’ had been hand-painted and carefully splashed (in contrast to those of the pink marbles which appear to have been achieved more casually). Still more pieces came from a pale band with hand-painted veins, representing giallo antico, a kind of yellow marble from North Africa.

While these schemes may not have all been in place at the same time, the building’s interiors had clearly been designed to impress. Perhaps there was an element of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ at work, as Roman Southwark seems to have boasted a number of elegantly appointed residences. One of the most impressive examples was excavated by MOLA (then MoLAS) at Winchester Palace, a short distance from The Liberty, in 1983-1990. There, beneath the 12th-century bishop’s residence that gives the site its name, archaeologists found part of a high-status Roman building – and within one of its rooms was a large section of painted plaster that had peeled away from its wall and collapsed face-down onto the floor (CA 124). Two superimposed skins of plaster had survived intact; the earlier of the pair, dating to the mid-2nd century, was the most ornate, combining architectural imagery depicting a colonnaded building, sweeping swathes of garlands, and the figure of a cupid. These Classical details led some to suggest that a Mediterranean artist had been brought in to execute the work – certainly, it appears that no expense had been spared, as the fresco also featured expensive materials like imported red cinnabar and gold leaf. Then, probably in the 3rd century, the entire scene had been plastered over and repainted with a much plainer geometric design.

These changes echo evidence from The Liberty’s building, which was in use for around a century, and would have seen numerous reworkings and redecorations over this period – the plasterwork that we see today would not have been the work of one artist, or even one team, but of successive groups of artisans serving the changing tastes and budgets of different inhabitants. While examining the fragments of imitation stone and a white wall with vivid red and black bands and lines, Han highlighted examples where the surface had been pecked, creating keying to support a new layer of plaster that could be painted afresh. In other cases, successive layers were still in place, speaking of repeated replasterings, and, as at Winchester Palace, some of these later surfaces carried much plainer decorative schemes. This might reflect a room switching function from a public space to something more utilitarian, Han said, perhaps changing from client-facing to a storeroom. There is also a wider pattern of Roman frescos becoming simpler and less well-executed over time, he added; possibly because of a wider economic decline that placed fancy frescos beyond the reach of many (and, with no work on offer, the best artists may not have been motivated to train successors, essentially de-skilling the next generation), or perhaps representing a shift in fashion towards a more minimalist approach.

Secrets from the City

Elaborately decorated dwellings were not limited to the south side of the river, however; significant discoveries have also been made within the walls of Londinium itself. Over the last 40 years, successive excavations along Fenchurch Street (by MOLA’s forerunner, the Department of Urban Archaeology; Wessex Archaeology; and Pre-Construct Archaeology) have revealed quantities of painted plaster, including floral and foliage motifs, from numerous houses. Another major collection of plaster fragments was recovered by the DUA at 25-51 St Mary Axe in 1989-1990; like those from The Liberty, these had been dumped en masse, and their decorations speak of extensive areas of imitation marble (as well as hints of yellow panels).

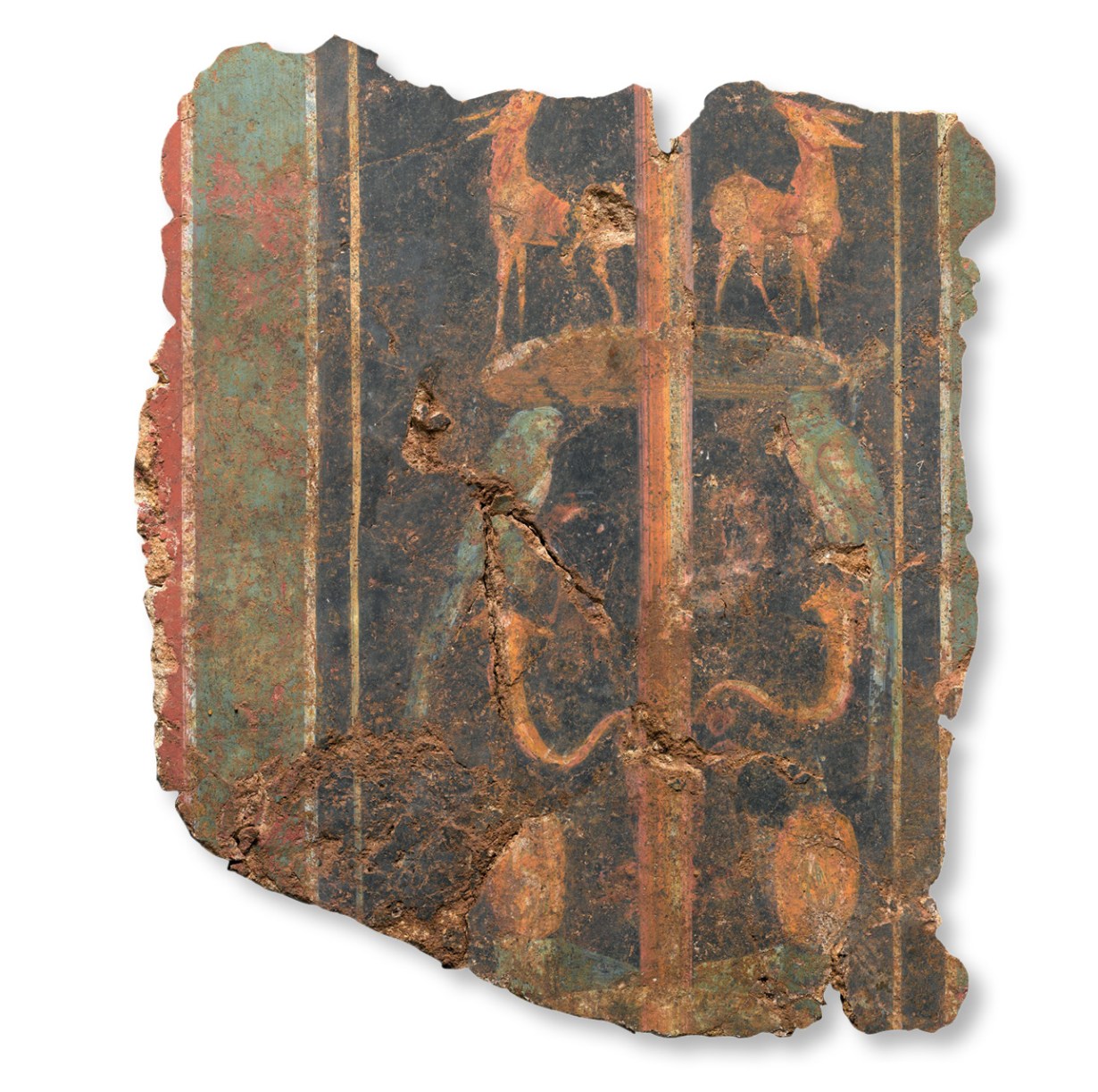

Elsewhere in the City, at 21 Lime Street, MOLA excavated the remains of a wealthy residence which had once stood close to London’s first forum (and was demolished when this public facility was expanded in the 2nd century). A collapsed wall preserved a large section of fresco measuring 2.5m by 1.5m (8.2ft by 4.9ft), revealing that one of its rooms had been painted with red panels interspersed with narrow green bands, as well as wider vertical stripes of black that were decorated with vines, theatrical masks, candelabra, deer, and parakeets (CA 320). This was not the first such find in the area; back in 2007, another MOLA dig at 8-13 Lime Street had uncovered another house with a collapsed plastered wall, this time boasting a yellow dado, red panels, and a green border that included images of flowers, birds, bunches of grapes, and candelabra (CA 226).

Timber and clay were the main building materials of early Roman London; their relatively humble nature holds the key to the survival of so many early frescos.

This list is not exhaustive, but the examples given above testify to the popularity of frescos within Roman London, as well as of certain ‘stock’ motifs, with foliage, birds, masks, and candelabra appearing at multiple locations. In his report on the St Mary Axe finds, published in the Transactions of the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society (volume 70, 2019), Ian M Betts wonders whether there might have been a school of specialist wall painters operating in London, in the same way that (based on stylistic comparisons) it is speculated that schools of mosaicists were working in different parts of Britain. We cannot know for sure, but the common design elements seen in different frescos of this period do at least offer illuminating insights into fashions of the time.

Another key characteristic shared by the houses mentioned above is that, despite the evident wealth of their inhabitants, their walls were constructed not from stone but from timber and clay. These were the main building materials of early Roman London, and their relatively humble nature holds the key to the survival of so many early frescos, Han said. Clay walls, sundried bricks, and wattle and daub held little reuse value, meaning that when buildings were demolished their materials were not robbed out and recycled elsewhere. For the same reason, plaster finds from stone buildings are much scarcer, and our understanding of how high-status buildings from the later Roman period – when London had many more masonry structures – were decorated is rather patchier.

Encountering the artists

As well as showcasing the skills of the artists who painted them, the fragmentary frescos from The Liberty also offer interesting insights into how such surfaces were created. Han showed me the outline of a flower that was never coloured in but was later painted over in white – perhaps it had been deemed surplus to requirements, or had been quickly sketched to instruct an apprentice tasked with creating more of the same – which reveals how such images were drawn using a compass. Just as illuminating, however, are hints of the process going wrong. Frescos are created by applying paint when the plaster is still wet, and the artists would have worked from the top down to prevent leaks from spoiling already completed sections. On one of the fragments of imitation stone, Han pointed out flecks of red that had spattered onto an area of black, suggesting somewhat rushed work. Perhaps the artist had been racing to finish the work because the plaster was drying too quickly – certainly, there are spots where the bonding had failed and the colour had flaked away, indicating that the surface had not been wet enough when the pigment was added. Elsewhere, a scar left by the clumsy movement of a trowel hints at someone else working with more haste than care – humanising details that bring the anonymous artisans back into focus.

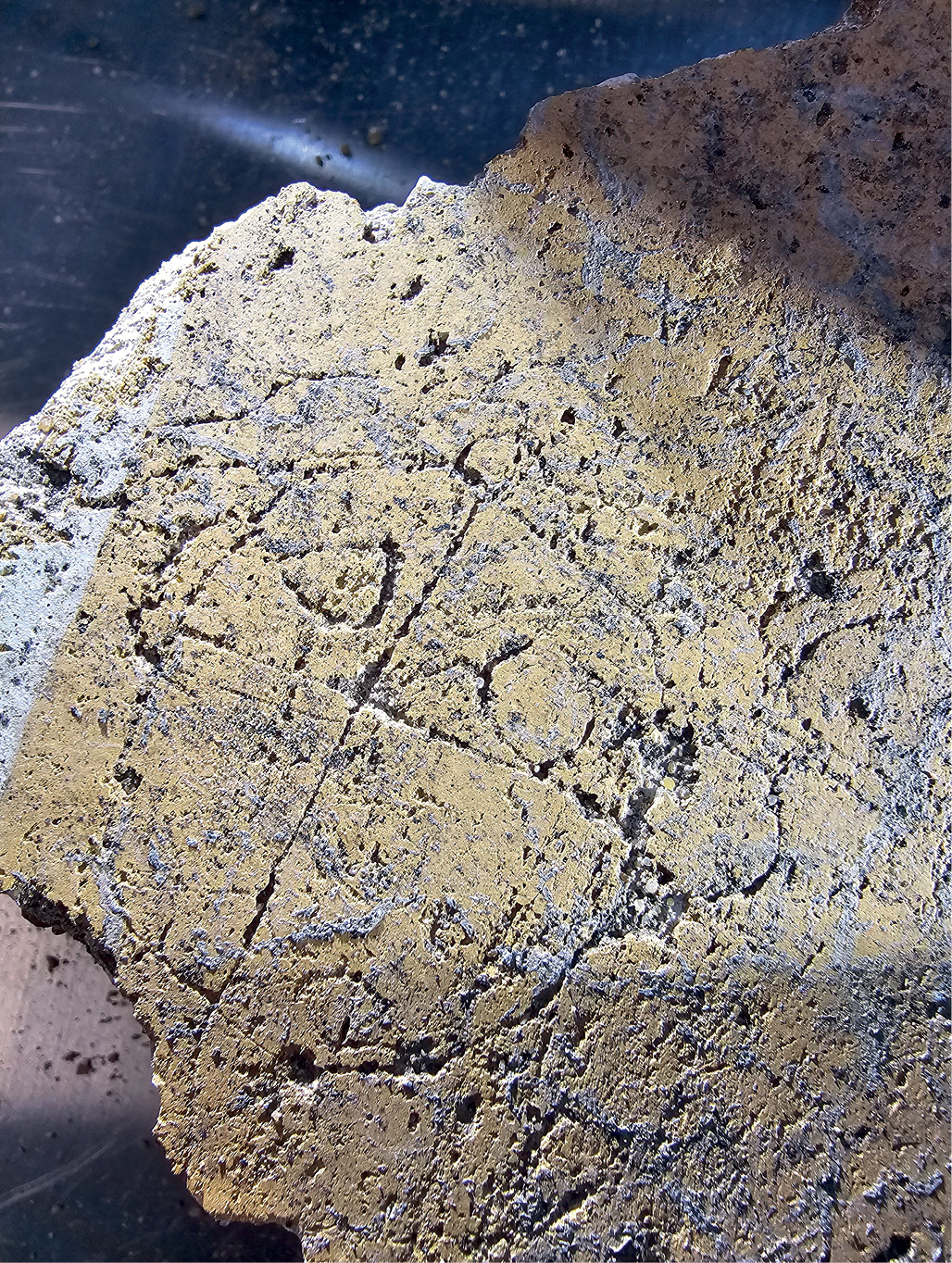

One of the artists had not intended to remain nameless, however. On one of the fragments, Han has identified part of a tabula ansata, an image of a decorative tablet which was used to sign artworks in the Roman world. Tantalisingly, the word ‘FECIT’ (‘made this’) has survived, but the name of the individual in question has broken away and has not yet been found. The crucial piece may yet emerge from the plaster still undergoing examination, but while its current absence is disappointing, the survival of the corresponding verb is more important, Han said. If it had been the other way around, with the name present and ‘FECIT’ lost, we would not know for certain that it represented one of the artists rather than captioning one of the images or representing another individual in some way. The text of the signature is skilfully executed (‘The “T” of “FECIT” goes from thin to thick, it is really beautiful penmanship,’ Han commented), and as the edges of the lettering have not flaked, it was very likely added while the plaster was still soft.

Elsewhere, similarly skilled writing is represented by a near-complete Greek alphabet, which was discovered across two pieces that have now been placed back together. It is the first example of its kind known from Roman Britain, though parallels are known from Italy (at Rome, Ostia, Pompeii, and Herculaneum), where they are thought to have served as some kind of tally or reference. The Southwark example does not look like casual writing practice either, Han commented – the letters are too well-executed (and too small to be a useful teaching aid) – rather, they suggest that someone in Southwark was able to use the Greek alphabet 2,000 years ago. Unlike the text of the tabula ansata, however, these letters had been scratched into the plaster when it was already dry – this was graffiti, not an integral part of the design. Nor was it the only example of a more casual addition to the plasterwork; another large fragment bears a drawing of a weeping woman with a distinctive hairstyle that was fashionable during the Flavian period (AD 69-96).

Analysis of the fragments is still ongoing, and the Southwark frescos may yet have many more secrets to reveal. The full results of this work will be published in due course, and the plaster pieces themselves will be preserved for future study, and the possibility of future display.

All images: © MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology)