Black is white means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this. But it means also the ability to believe that black is white, and more to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary: George Orwell. This is how the members of the fascist MQM were trained to say, believe, and know that black is white after its creation at the behest of dictator Zia-ul-Haq, sowing the seeds of ethnic hatred in Sindh to weaken Bhutto’s support base, and handing over Karachi to it. It played havoc with the peace and tranquillity of Karachi in 1988, 1991, 2002 to 2008, indulging in bloodshed, extortion, target killings, arson and torture.

It was this party which paraded the narrative of a second province in Sindh to accommodate the sons of the so-called makers of Pakistan. The party continues singing this hymn uninterrupted. Their forefathers made Pakistan in the lands of Bengalis, Sindhis, Pathans, Baloch and Punjabis instead of UP, CP and Delhi. They are in the minority in Karachi. Katchhi Memons, Baloch, Brohis, Punjabis, Pathans – put together – outnumber them. They have now come down to creating a new province in the ‘abandoned or evacuee Sindh’. Could there be any more absurd argument? Is Sindh – with its history of thousands of years – an abandoned territory? They took all the evacuee properties from 1948-1969.

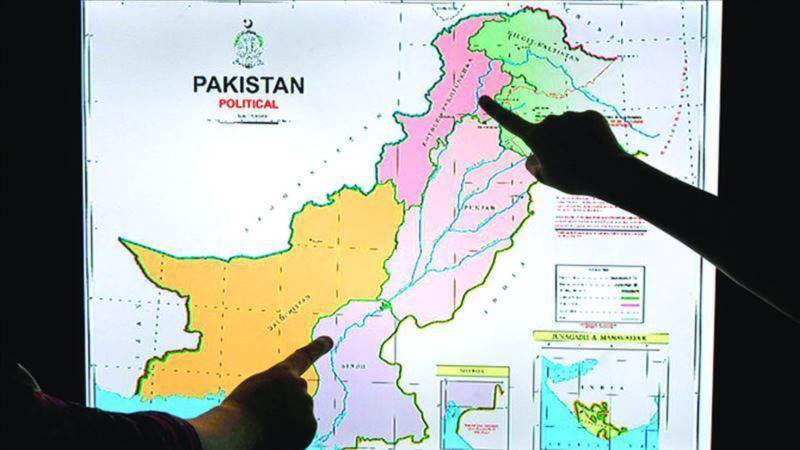

We cannot figure out a Sindh without Karachi and Hyderabad and half of Mirpurkhas divisions – a torso with its upper part chopped off, a land dispossessed of its historical heritage, of its centuries-old links with the Arabian Sea and Sindh Delta, of its coastal area of 350 kilometres and seaports, of its economic, financial and industrial hub, of its health, educational, literary and intellectual centres. What would remain with the lower Sindh – divisions of Sukkur, Larkana and Nawabshah?

Sindhis would not accept this, nor would they want to relive the bloodshed of past decades. We must keep in mind their successful struggles against the annexation of Sindh to the Bombay Presidency; the federalisation of Karachi; the territorial amalgamation of Sindh in the One-Unit; the restoration of democracy in 1984; the Kalabagh Dam and the recent protests over the construction of unauthorised canals. Sindhis are federal-minded but unwilling to make any compromises about their political and economic autonomy, as well as the territorial integrity of Sindh. The proposition of dividing Sindh would reignite the ethnic tension and bloodshed of the past decades, shaking the federal foundations of the country.

This balkanisation of Balochistan will engender ethnic conflicts of greater enormity, leading to decades of strife, chaos and anarchy

The modern Balochistan or Khanate of Kalat was established in 1666. The Khanate lost considerable territories to invading armies from the west and north. The Indian British forces also compelled the Khanate in 1838-1839 to allow the Empire a corridor from Khangarh (Present Jacobabad) to Quetta with a cantonment to monitor the Great Game. The Khanate accepted this in exchange for regular financial assistance, defence from the west and east, and full internal autonomy. The Khan of Kalat was in favour of Pakistan and extended financial assistance to AIML by weighing the Quaid in gold and silver. A tripartite Standby agreement was signed between the representatives of AIML (Quaid-e-Azam and others), Khanate of Kalat (Prime Minister and the Chief Secretary of Khanate) and British India on 3rd June 1947. It was agreed that Balochistan being out of the Indian possessions of the Empire, would maintain its independence as it stood in 1838 with special relations with Pakistan (Inside Balochistan – Memoirs of Mir Ahmed Yar Khan).

Mir Ahmed Yar Khan, Khan of Kalat, visited Pakistan in October 1947. He was accorded the protocol of a Head of State. The Khan was apprehensive about Pakistan’s direct contacts with the semi-autonomous regions of the Khanate – Las Bella and Kharan – to join it. These differences intensified and resulted in the siege of Kalat in March 1948 and the surrender by the Khan of Kalat in April 1948.

The Khan writes in his memoirs that he overstepped his authority to surrender, in violation of the Resolution passed by the Balochistan Legislative Assembly for Independence. He says he did so to avoid mayhem. This triggered the first insurgency in Balochistan, spearheaded by Prince Abdul Karim. When the province was amalgamated into One-Unit in 1955, the Baloch again took up arms in the second rebellion led by Nawab Nauroz Khan Zehri. The third rebellion in this volatile province was triggered by the dismissal of the elected government of Attaullah Mengal in July 1973. The violent death of Sardar Akbar Khan Bugti sparked the fourth insurgency, which remains aglow to this day. Baloch have never accepted the mistreatment of their land.

The proposition of dividing their land into four provinces on an ethnic basis is tantamount to stirring the hornet’s nest. Would it be advisable to balkanise such a volatile province on ethnic basis – to favour pro-establishment dynasties in Sahili Balochistan (Jams), Shumali Balochistan (Pathans) and East Balochistan (Jamali, Magsi, Rind, Domki tribes) and restrain and restrict the perceived anti-establishment tribes in the Wasti Balochistan (Brohi)? This balkanisation of Balochistan will engender ethnic conflicts of greater enormity, leading to decades of strife, chaos and anarchy.

After the secession of East Pakistan, the centrifugal forces had become too assertive. Therefore, the framers of the 1973 Constitution laid down a tough process for the establishment of new provinces requiring two-thirds majority votes from the Provincial Assemblies and the Parliament. The Constitutional barricade of a two-thirds majority may be surmounted as we witnessed in the case of the 26th Constitutional Amendment.

However, the economic, financial and administrative issues provoked by the creation of new provinces including, as elaborated by Dr Ishrat Hussain, division of assets and liabilities, additional costs on offices, secretariats and Ministers, handling legal disputes, restructuring administration, reassigning civil servants, delimiting constituencies, and redrawing boundaries would be administratively, economically and politically unsustainable for Pakistan with chronically weak federal bonds, broken institutional systems of governance, and a corrupt economy.