Note: This article was written by University of Illinois Agricultural and Consumer Economics M.S. student Yu-Chi Wang and edited by Joe Janzen. It is one of several excellent articles written by graduate students in Prof. Janzen’s ACE 527 class in advanced agricultural price analysis this fall.

Soybean oil and palm oil are the two most widely available vegetable oils in the world and are substitutes in many products, including as feedstocks in the production of biofuels. For many years, soybean oil and palm oil prices moved together, but since 2020, the close co-movement between soybean oil and palm oil prices has weakened. Prices now diverge more often and for longer periods. This change suggests that the types of supply and demand shocks hitting these markets has shifted. We suggest these shocks are becoming less global and more regional or national; aggregate vegetable oil supply and demand still matter, but these now interact with region-specific disruptions, particularly those related to biofuels policy, that affect one oil more than the other.

The goal of this article is to document how the price relationship between soybean oil and palm oil has changed and what this change means for future price dynamics. We first describe the global roles of soybean and palm oils and the different production systems behind them. We use monthly and daily prices to show how their historical co-movement has broken down since 2020. We then draw on several recent market episodes to explain soybean-palm price divergences and end with implications for U.S. soybean oil and future biofuel policy.

Overview of Global Vegetable Oil Production

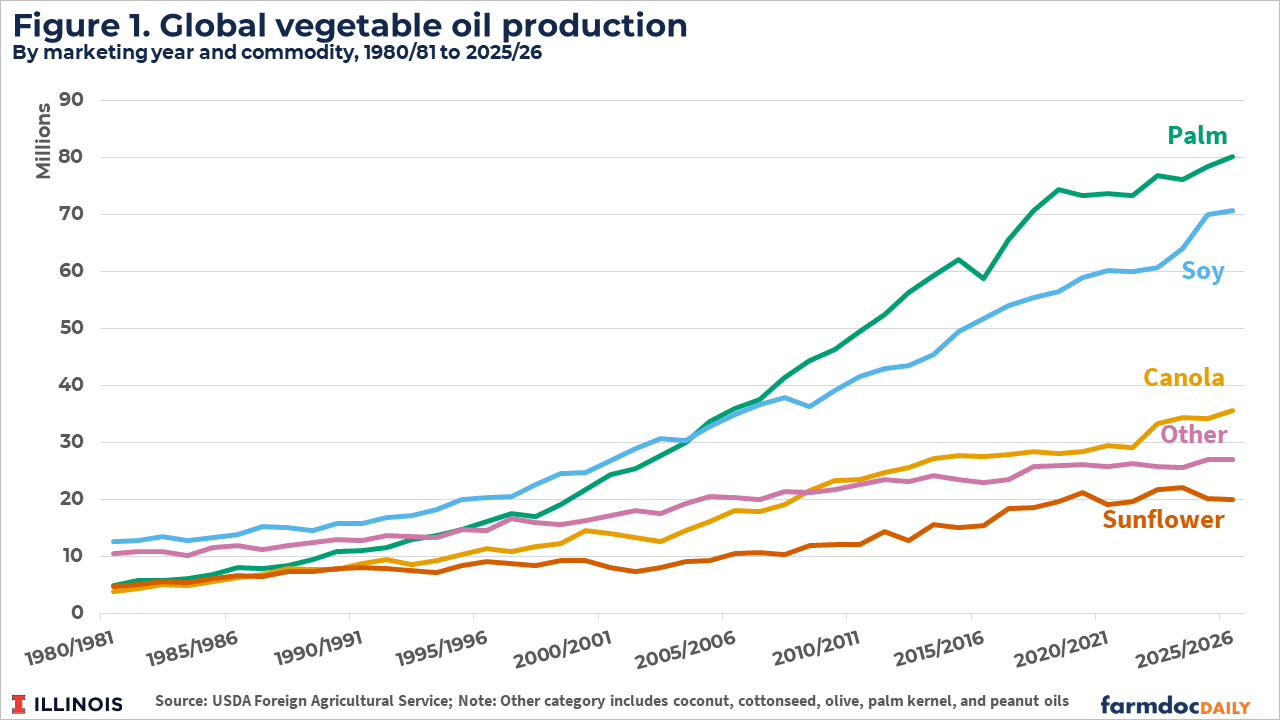

Soybean oil and palm oil are the two leading vegetable oils in the world, a position they have held since the 1980s when palm oil surpassed production of canola and sunflower oils. Figure 1 plots changes in the production of leading vegetable oils over time. Soybean oil was long the world’s largest vegetable oil, but global production of palm oil began to exceed soybean oil beginning in the 2004/2005 marketing year. Together, they account for more than 60s% of global edible oil supply. Other vegetable oils such as canola, sunflower, and others play an important but mainly supporting role in meeting global demand.

The location of soybean and palm production and the process for extracting oil are important differences between the two commodities. Palm oil production is heavily concentrated in Indonesia and Malaysia, where output expanded rapidly in the 2000s. Palm oil refining, logistics, and trade are strongly geographically clustered. Soybean oil production is less concentrated than palm oil but focused in large agricultural exporting countries such as the United States, Brazil, and Argentina and major soybean importers, principally China. Major exporting nations typically have varying forms of biofuels mandates that incentivize domestic demand for soybean or palm oil as a feedstock and these mandates typically target domestically produced feedstock. Structural differences in location and policy may help explain why the two oil markets may not always respond in the same way to changes in demand.

Historical Price Relationships

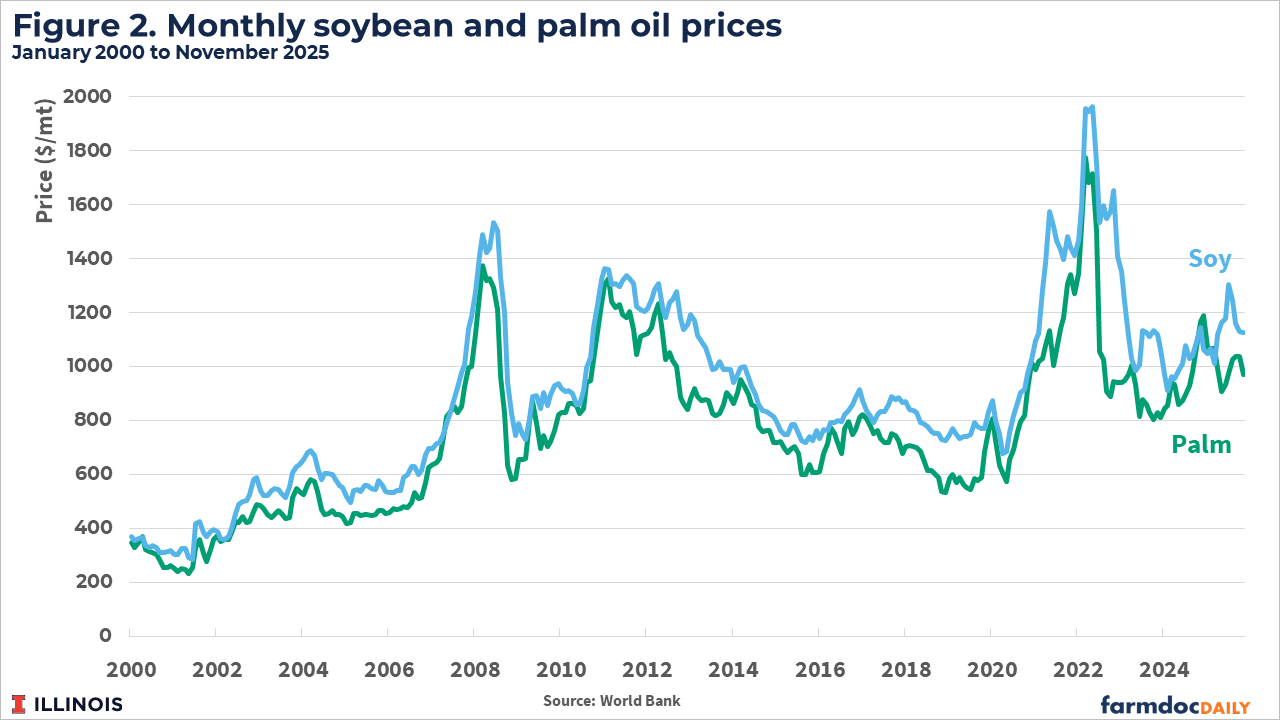

To the extent that vegetable oils are substitutable and trade costs like transportation, tariffs, and others are low, soybean and palm prices should move closely together. To document this connection over a long time period, we analyze monthly benchmark prices tracked by the World Bank’s so-called ‘Pink Sheets’. These prices represent vegetable oils delivered to ports in Northwest Europe so they account for location differences. Figure 2 shows historic prices for both soybean and palm oil since 2000. While soybean oil has typically been valued at a slight premium to palm oil, prices have typically moved closely together over this period. Increases in prices correspond to increases in the other. Episodes like the 2008 price spike that affected many agricultural and energy prices are common to both series and the gap between prices has remained fairly stable over time. Despite substantial changes in price levels, the difference or ratio between soybean and palm oil prices was generally stable, at least until about the year 2020.

After 2020, soybean and palm oil prices begin to diverge more often and for longer periods. Before and after the 2022 price spike that coincides with another broad increase in agricultural and energy prices, prices for soybean oil surged well above palm oil prices. In other cases, soybean and palm oil prices appear to move in opposite directions. In late 2024, palm oil futures prices actually exceeded soybean prices for the first time since the 1990s. While some common dynamics remain part of price behavior after 2020, Figure 2 suggests more volatility in the underlying economic forces driving vegetable oil supply and demand. These patterns indicate that the close and predictable price relationship seen before 2020 has fundamentally changed.

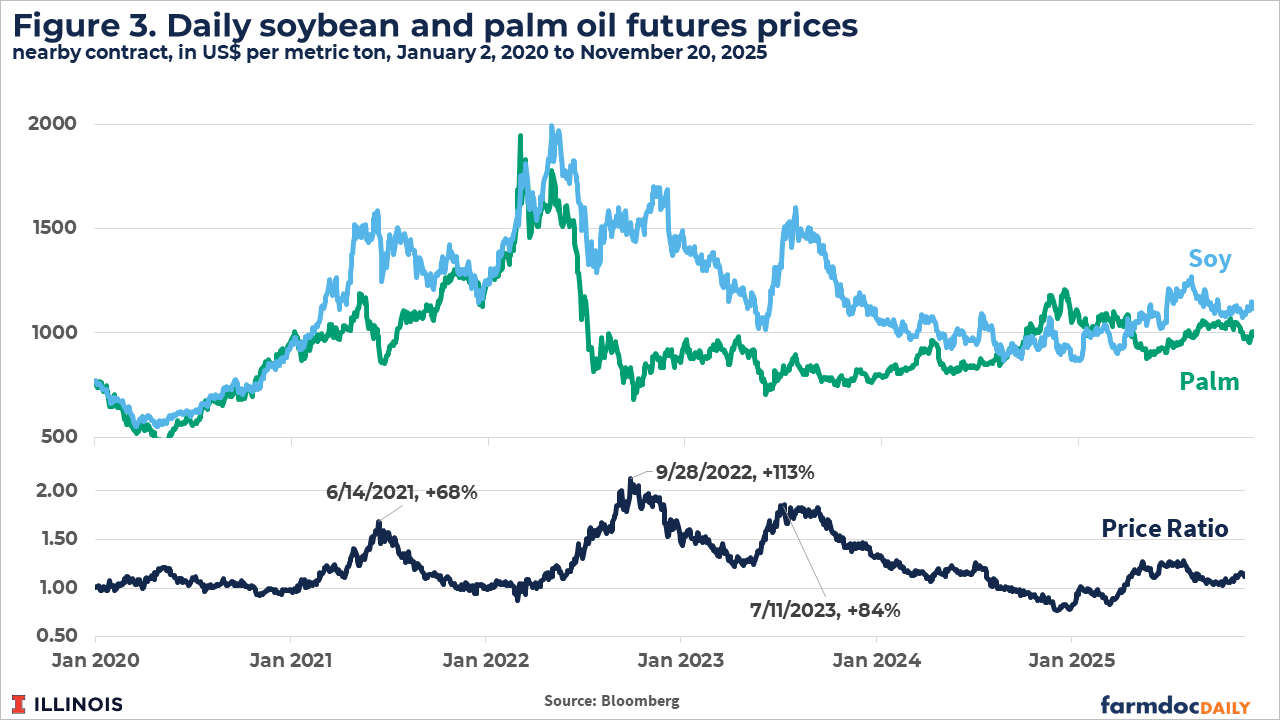

To assess soybean and palm oil price dynamics since 2020 in greater detail, we look at daily futures price data. Daily data provide a more granular look at the timing of particular price movements. To make prices comparable across markets, soybean oil and palm oil prices must be adjusted, as they trade on different exchanges and are quoted in different units and currencies. Soybean oil prices are taken from Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) front-month futures and are quoted in U.S. cents per pound. Crude palm oil prices are taken from Bursa Malaysia Derivatives (BMD) front-month futures and are quoted in Malaysian ringgit per metric ton. To place both series on a common basis, soybean oil prices are expressed per ton, while palm oil prices are converted from Malaysian ringgit to U.S. dollars using the daily MYR–USD exchange rate from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Figure 3 shows daily nearby soybean oil and palm oil futures prices from January 2020 to November 2025, both in levels and in terms of the price ratio of soybean to palm oil. Prices diverge beginning in early 2021. The price ratio returns to near parity during the early 2022 commodity price spike, but there is a second sharp divergence as prices for both commodities fell off of early 2022 highs. In mid 2023, prices diverge again with soybean oil prices jumping sharply. The price ratio reaches parity in mid-2024, after which palm oil prices exceed soybean oil prices for a time. Soybean oil prices have been slightly above palm oil prices for much of the past year. Overall, this period features more volatility in the price ratio and longer and sharper divergences in price than seen in past periods.

Why did the Soybean Oil-Palm Oil Price Relationship Break Down?

To understand price divergences shown in Figure 3, we consider narrative explanations coincidental to observed price movement. We highlight three episodes where soybean prices diverged from palm oil prices.

The first occurs over calendar year 2021. Both soybean oil and palm oil prices rise sharply during this period, reflecting tight global vegetable oil supplies. However, soybean oil prices increase more than palm oil prices; at the peak of this divergence indicated in Figure 3, the soybean oil price was 68% higher than the palm oil price. This coincides with a surge in US renewable diesel capacity and production (USDA-FAS, 2024), leading to a stronger increase in demand for soybean oil as a feedstock. Although programs such as the Renewable Fuel Standard and California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard had been in place for years, renewable diesel production rapidly increased during this period which may have helped push soybean oil prices higher.

By late 2021, this divergence begins to narrow. Palm oil prices move higher as Malaysia experiences La Niña-related adverse weather and a shortage of migrant harvest workers following COVID-19 border restrictions (McKeany-Flavell, 2022). Malaysian palm oil production, exports, and year-end stocks fall to multi-year lows, which coincides with palm oil prices reaching record or near-record levels. As palm oil prices rise more quickly, the soybean-oil premium narrows, and by late 2021 the two prices move back together, ending the first divergence episode.

The second divergence begins after both prices reach record highs in early 2022. These peaks in Figure 3 occur during a period of very tight global supplies associated with the Russia-Ukraine war and Indonesia’s temporary ban on palm oil exports. Indonesia lifted the export ban in late May 2022 and exports resumed, leading palm oil prices to fall sharply. Soybean oil, as a close substitute, also moves lower but declines more gradually. As palm oil falls more quickly, the soy-to-palm price ratio increases, peaking with soybean oil prices 113% percent (i.e. more than double) palm oil in September 2022.

Toward the end of 2022, this divergence starts to narrow. In December 2022, EPA releases proposed biofuel mandates for 2023 to 2025 that are lower than the market had anticipated. This announcement may have reduced projected renewable diesel demand for soybean oil and is followed by a sharp decline in soybean oil prices (Sterk, 2022). As soybean oil prices fall more quickly and begin to move back toward palm oil’s earlier decline, the two price series return to a more stable relationship. This marks the end of the second divergence.

The third divergence begins in mid-2023, when markets appear to become more concerned about U.S. weather and the possibility of drought reducing soybean yields. As of mid-June 2023, about half of the U.S. soybean crop is classified in drought categories and crop condition ratings are declining across much of the Corn Belt (Purdue Center for Commercial Agriculture, 2023). At the same time, short-term weather forecasts point to a continuation of dry conditions, and soybean futures move sharply higher in a way that is consistent with this combination of poor current conditions and ongoing drought risk.

Beginning around September 2023, soybean oil prices in Figure 3 start to fall sharply and continue to decline into early 2024. Clean Fuels Alliance America (2024) reports that generation of biomass-based diesel Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) in 2023 substantially exceeded the biomass-based diesel mandate and that RIN values declined sharply as this oversupply became apparent. RINs are tradable compliance credits that fuel suppliers use to show they have met U.S. renewable fuel blending requirements. Because soybean oil is an important feedstock for biomass-based diesel, this combination of abundant credits and lower RIN values is consistent with a reduced willingness to pay high prices for soybean oil in fuel uses and may have contributed to the downward pressure on soybean oil prices during this period. As soybean oil prices fall more than palm oil prices and the relative price in Figure 3 moves back to a more normal range in mid-2024 marking the end of the third divergence.

Discussion

We show the long-standing tight connection between soybean oil and palm oil prices has changed in recent years. Since 2020, leading vegetable oil price benchmarks have diverged more often and for longer periods. Co-movement has weakened and the two markets now follow separate paths more frequently than in the past. Evidence from recent market episodes suggests that this shift reflects a new mix of shocks. Broad global demand and cost shocks still move both markets, but they now interact with more frequent policy shocks and region-specific disruptions. In this environment, even close substitutes like soybean oil and palm oil can depart from their historical pattern of co-movement.

Our analysis suggests the US soybean industry may be more insulated from global vegetable oil shocks: palm oil may not play the same role it once did in shaping soybean oil prices. Palm oil production growth has slowed as Southeast Asia’s plantations hit land limits and a larger share of trees move into older age. Expansion has largely given way to replanting, so future output gains are likely to be small even if prices stay high (Bloomberg Intelligence, 2024). A larger share of palm oil production now stays in Southeast Asia to meet domestic biodiesel and food demand. This means palm oil has less effect on global vegetable oil prices than in the past, although major changes in palm oil supply and demand may still be transmitted to global vegetable oil markets. At the same time, the US soybean industry is now more exposed to domestic biofuels policy shocks. The rising importance of soybean oil as a biofuels feedstock in US has increased the importance of domestic policy decisions, such as blending incentives and volume obligations, in driving U.S. soybean oil use and price.

Our central conclusion is that there is no longer a single global vegetable oil market signal. To an increasing degree, farmers, crushers, renewable fuels producers, and policymakers need to watch both broad global shocks and more local, product-specific shocks. That means tracking not only world demand and overall stocks, but also U.S. biofuel policy decisions, biodiesel and export rules in Indonesia and Malaysia, and weather and crop developments in South America and Southeast Asia. Managing soybean oil price risk in this new environment requires paying attention to all these moving parts, not just a single commodity price.