AI technologies need to be safe and transparent. There are few, if any, benefits from being outside efforts to achieve this. Credit: George Chan/Getty

You don’t need to be an oracle to know that the coming year will see further advances in artificial intelligence, as updated and new models, publications and patents continue their inexorable rise. If current trends are a reliable guide, many countries will also be enacting more AI-related laws and regulations. In 2023, at least 30 such laws were passed around the world, according to the Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025, produced by researchers at Stanford University in California. The following year saw another 40.

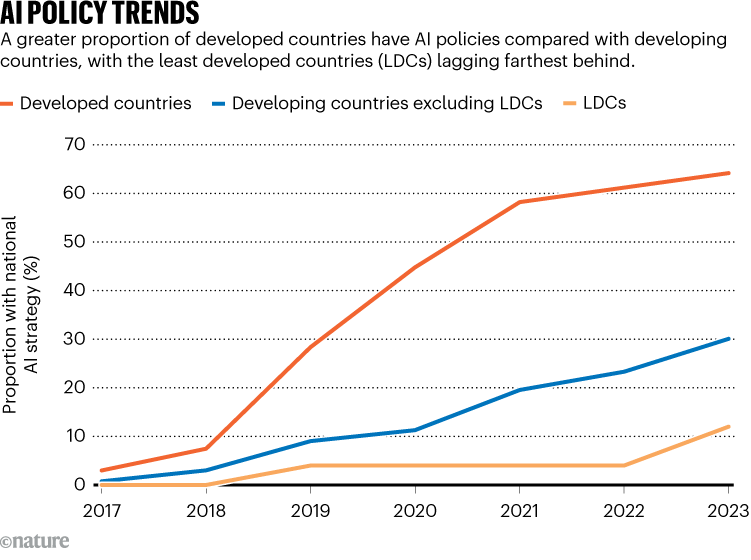

Over the past couple of years, AI lawmaking has been busiest in the East Asia and Pacific region, in Europe and in individual US states. Between them, US states passed 82 AI-related bills in 2024. But there are some notable cold spots, too: there has been relatively little activity in low and lower-middle-income countries (see ‘AI policy trends’). Meanwhile, the US federal government is bucking the trend by cancelling AI policy work and challenging state-level AI laws.

Source: UNCTAD based on data from the 2024 AI Index report.

This must be the year that more lower-income countries start regulating AI technologies, and that the United States is persuaded of the dangers of its approach. The country is one of the biggest markets for AI technologies, and people around the world are using models developed mainly by US companies. All nations need AI laws and policies, regardless of their position on the spectrum of producers and consumers. It’s impossible to imagine the technologies used in energy, food production, pharmaceuticals or communications being outside the ambit of safety regulation. The same should be true of AI.

There is a growing international consensus. The authorities in China, for example, are taking AI regulation extremely seriously, as are those of many European countries. Most of the rules of the European Union’s AI Act are expected to come into force in August. In 2024, the African Union published continent-wide guidance for AI policymaking. There are also moves to establish a global organization for cooperation on AI, possibly through the United Nations.

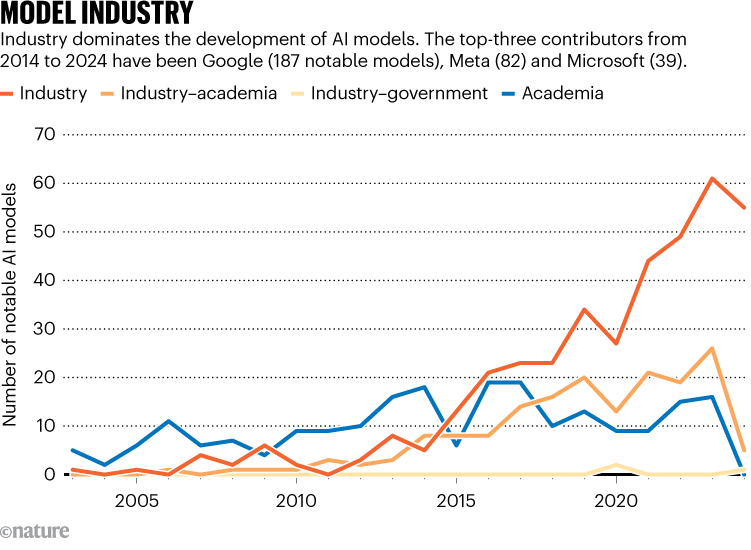

A wide spectrum of national and regional laws and regulations are in place or under development. Some countries, for example, are looking to ban ‘deepfake’ videos. This should be a universal goal. Companies should also provide details of the data used to train models, and need to ensure that copyright is respected in the training process. The overriding ambition must be to achieve regulations similar to those governing other general-purpose technologies. AI developers — most of which are companies (see ‘Model industry’) — need to transparently explain how their products work, demonstrate that their models have been produced through legal means, and show that the technology is safe and that there is accountability for risks and harm. Transparency is also needed from researchers, more of whom need to publish their models in the peer-reviewed literature.

Source: 2025 Stanford AI Index report.

According to UNCTAD, the UN trade-policy agency for low- and middle-income countries, two-thirds of high-income countries and 30% of middle-income countries had AI policies or strategies in place at the end of 2023, but little more than 10% of the lowest-income countries did. These nations need to be supported in their AI-regulatory efforts.

There is also a need to engage with the United States. On taking office, President Donald Trump cancelled a programme set up by the previous administration through which the National Institute of Standards and Technology had started to scope out AI standards with technology companies. In December, an executive order was issued forbidding state laws that conflict with White House AI policy.

The leaders of some technology companies seem to be satisfied with this direction of travel. But others know that good regulations give companies consistency in standards and allow them to plan predictably for the long term. Light-touch regulation, or no regulation at all, is in neither their nor their customers’ interests.

Civil servants working at regulatory agencies know that better regulation is needed, both to protect people, particularly children, from harm and to reassure consumers. They can see that there is considerable public anxiety about the risks of AI, fuelled, in part, by companies’ stated ambition to work towards artificial general intelligence. And they can hear the voices of those in the AI research community, including some of the field’s pioneers, who are warning of possible existential risks from uncontrollable AI.

Officials in the Trump administration have said that regulation will risk the United States losing the AI race with China. But, as Nature’s news team has reported (Nature 648, 503–505; 2025), China is exploring an alternative path to innovation. Its AI companies are creating innovative products, using technologies that are more open than those of US counterparts, and working to nationwide regulations that require more disclosure.

Technology companies know that their business models rely on public cooperation, particularly when it comes to access to data. That cooperation will evaporate if people lose confidence that their data are safe and being used responsibly, or learn that AI products are harming people.

AI is potentially a transformative technology. However, we don’t know how that will manifest, or what impact it will have. Many countries are rightly being cautious and assessing risks, but more coherence is needed in policymaking. Nations should work together to design policies that not only enable development, but also incorporate guardrails. Let 2026 be the year everyone agrees on that.