On September 14, 2015, a signal arrived on Earth, carrying information about a pair of remote black holes that had spiraled together and merged. The signal had traveled about 1.3 billion years to reach us at the speed of light—but it was not made of light. It was a different kind of signal: a quivering of space-time called gravitational waves first predicted by Albert Einstein 100 years prior. On that day 10 years ago, the twin detectors of the US National Science Foundation Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (NSF LIGO) made the first-ever direct detection of gravitational waves, whispers in the cosmos that had gone unheard until that moment.

The historic discovery meant that researchers could now sense the universe through three different means. Light waves, such as X-rays, optical, radio, and other wavelengths of light, as well as high-energy particles called cosmic rays and neutrinos, had been captured before, but this was the first time anyone had witnessed a cosmic event through the gravitational warping of space-time. For this achievement, first dreamed up more than 40 years prior, three of the team’s founders won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics: MIT’s Rainer Weiss, professor of physics, emeritus (who recently passed away at age 92); Caltech’s Barry Barish, the Ronald and Maxine Linde Professor of Physics, Emeritus; and Caltech’s Kip Thorne, the Richard P. Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics, Emeritus.

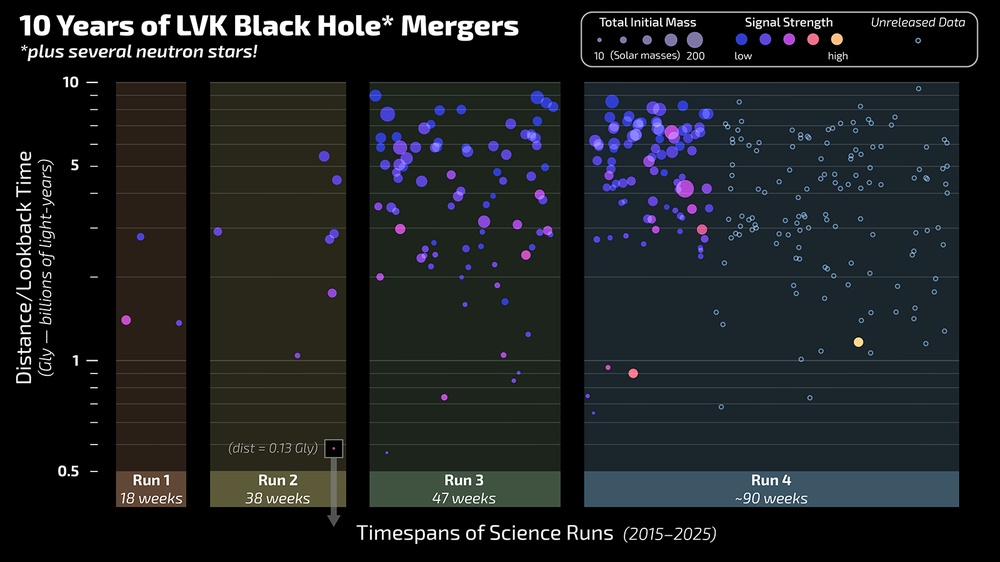

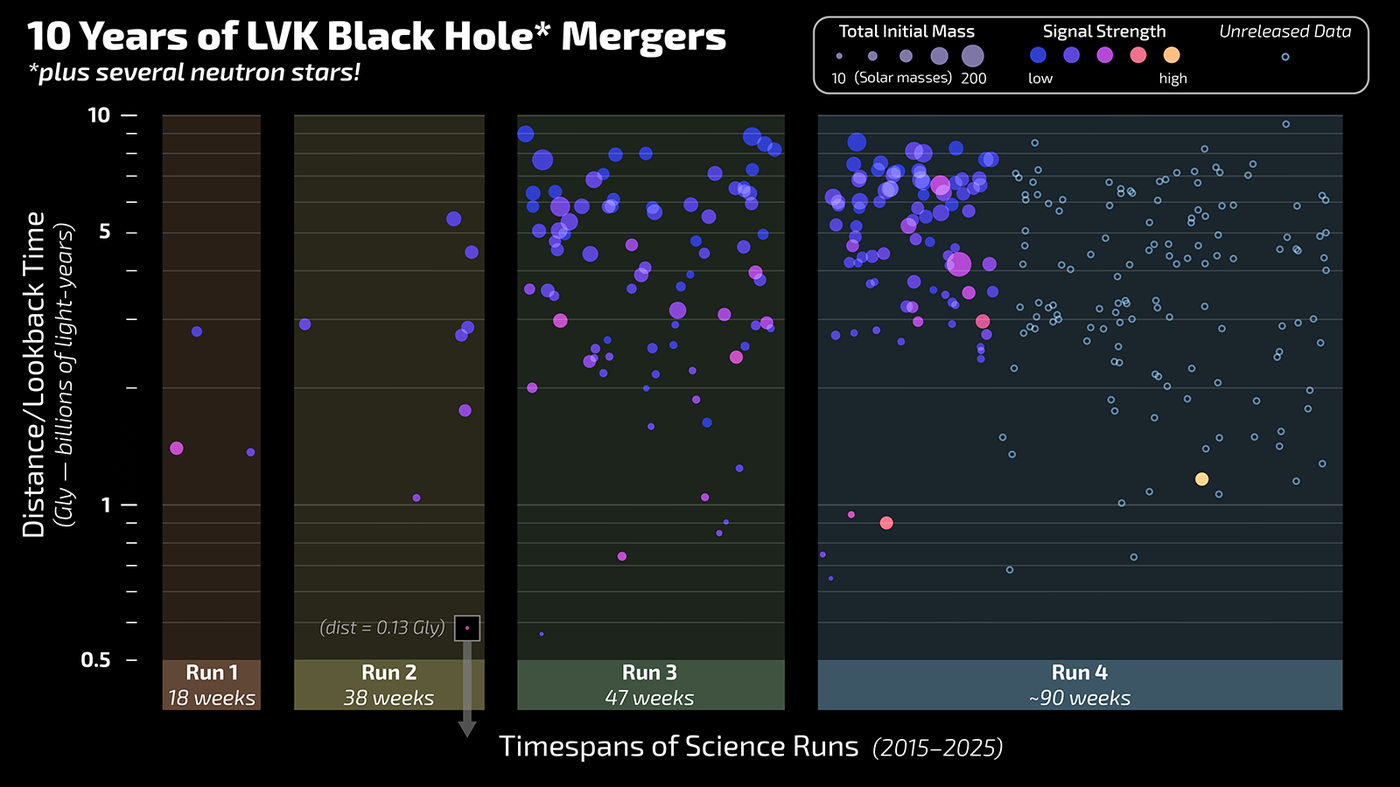

Today, LIGO, which consists of detectors in both Hanford, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana, routinely observes roughly one black hole merger every three days. LIGO now operates in coordination with two international partners, the Virgo gravitational-wave detector in Italy and KAGRA in Japan. Together, the gravitational-wave-hunting network, known as the LVK (LIGO, Virgo, KAGRA), has captured a total of about 300 black hole mergers, some of which are confirmed while others await further analysis. During the network’s current science run, the fourth since the first run in 2015, the LVK has discovered more than 200 candidate black hole mergers, more than double the number caught in the first three runs.

The dramatic rise in the number of LVK discoveries over the past decade is owed to several improvements to their detectors—some of which involve cutting-edge quantum precision engineering. The LVK detectors remain by far the most precise rulers for making measurements ever created by humans. The space-time distortions induced by gravitational waves are incredibly miniscule. For instance, LIGO detects changes in space-time smaller than 1/10,000 the width of a proton. That’s 700 trillion times smaller than the width of a human hair.

“Rai Weiss proposed the concept of LIGO in 1972, and I thought, ‘This doesn’t have much chance at all of working,’” recalls Thorne, an expert on the theory of black holes. “It took me three years of thinking about it on and off and discussing ideas with Rai and Vladimir Braginsky [a Russian physicist], to be convinced this had a significant possibility of success. The technical difficulty of reducing the unwanted noise that interferes with the desired signal was enormous. We had to invent a whole new technology. NSF was just superb at shepherding this project through technical reviews and hurdles.”

MIT’s Nergis Mavalvala, the Curtis and Kathleen Marble Professor of Astrophysics and dean of the School of Science, says that the challenges the team overcame to make the first discovery are still very much at play. “From the exquisite precision of the LIGO detectors to the astrophysical theories of gravitational-wave sources, to the complex data analyses, all these hurdles had to be overcome, and we continue to improve in all of these areas,” Mavalvala says. As the detectors get better, we hunger for farther, fainter sources. LIGO continues to be a technological marvel.”

The Clearest Signal Yet

LIGO’s improved sensitivity is exemplified in a recent discovery of a black hole merger referred to as GW250114 (the numbers denote the date the gravitational-wave signal arrived at Earth: January 14, 2025). The event was not that different from LIGO’s first-ever detection (called GW150914)—both involve colliding black holes about 1.3 billion light-years away with masses between 30 to 40 times that of our Sun. But thanks to 10 years of technological advances reducing instrumental noise, the GW250114 signal is dramatically clearer.

“We can hear it loud and clear, and that lets us test the fundamental laws of physics,” says LIGO team member Katerina Chatziioannou, Caltech assistant professor of physics and William H. Hurt Scholar, and one of the authors of a new study on GW250114 published in the Physical Review Letters.

By analyzing the frequencies of gravitational waves emitted by the merger, the LVK team provided the best observational evidence captured to date for what is known as the black hole area theorem, an idea put forth by Stephen Hawking in 1971 that says the total surface areas of black holes cannot decrease. When black holes merge, their masses combine, increasing the surface area. But they also lose energy in the form of gravitational waves. Additionally, the merger can cause the combined black hole to increase its spin, which leads to it having a smaller area. The black hole area theorem states that despite these competing factors, the total surface area must grow in size.

Later, Hawking and physicist Jacob Bekenstein concluded that a black hole’s area is proportional to its entropy, or degree of disorder. The findings paved the way for later groundbreaking work in the field of quantum gravity, which attempts to unite two pillars of modern physics: general relativity and quantum physics.

In essence, the LIGO detection allowed the team to “hear” two black holes growing as they merged into one, verifying Hawking’s theorem. (Virgo and KAGRA were offline during this particular observation.) The initial black holes had a total surface area of 240,000 square kilometers (roughly the size of Oregon), while the final area was about 400,000 square kilometers (roughly the size of California)—a clear increase. This is the second test of the black hole area theorem; an initial test was performed in 2021 using data from the first GW150914 signal, but because that data was not as clean, the results had a confidence level of 95 percent compared to 99.999 percent for the new data.

Thorne recalls Hawking phoning him to ask whether LIGO might be able to test his theorem immediately after he learned of the 2015 gravitational-wave detection. Hawking died in 2018 and sadly did not live to see his theory observationally verified. “If Hawking were alive, he would have reveled in seeing the area of the merged black holes increase,” Thorne says.

The trickiest part of this type of analysis had to do with determining the final surface area of the merged black hole. The surface areas of pre-merger black holes can be more readily gleaned as the pair spiral together, roiling space-time and producing gravitational waves. But after the black holes coalesce, the signal is not as clear-cut. During this so-called ringdown phase, the final black hole vibrates like a struck bell.

In the new study, the researchers precisely measured the details of the ringdown phase, which allowed them to calculate the mass and spin of the black hole and, subsequently, determine its surface area. More specifically, they were able, for the first time, to confidently pick out two distinct gravitational-wave modes in the ringdown phase. The modes are like characteristic sounds a bell would make when struck; they have somewhat similar frequencies but die out at different rates, which makes them hard to identify. The improved data for GW250114 meant that the team could extract the modes, demonstrating that the black hole’s ringdown occurred exactly as predicted by math models based on the Teukolsky formalism—devised in 1972 by Saul Teukolsky, now a professor at Caltech and Cornell.

Another study from the LVK, submitted to Physical Review Letters today, places limits on a predicted third, higher-pitched tone in the GW250114 signal, and performs some of the most stringent tests yet of general relativity’s accuracy in describing merging black holes.