Mikaela Strauss, the songwriter and producer who records as King Princess, describes her new album Girl Violence as “almost like a ‘ha ha’ to toxic masculinity”, although not in the way you may initially think. Informed by the drama and infighting that she suggests is inherent in many lesbian communities, Girl Violence touches on the idea that “in a world full of physical violence and anger and war and hypermasculinity, this is the really crazy violence that’s under the surface, that’s subliminal and emotional and thoughtful”, she says. She smirks a little, over Zoom from her home in Brooklyn: “You think that you’re the proprietor of the violence. [But] it’s the girls.”

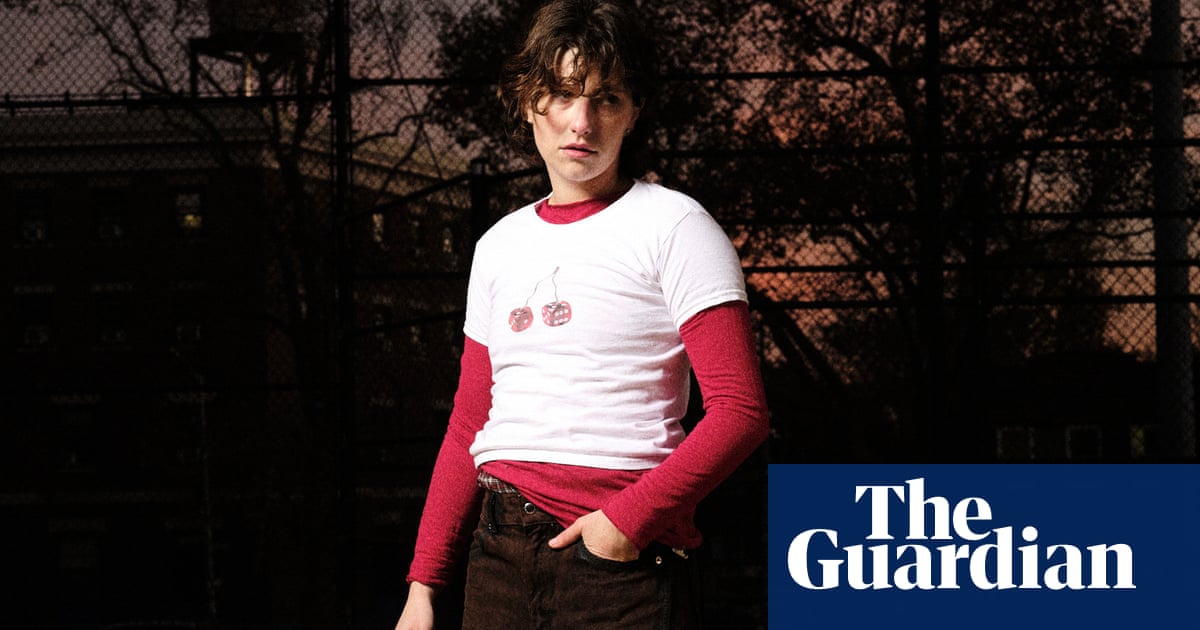

Girl Violence is the third King Princess album, and the most fully formed. It represents something of a clean break for 26-year-old Strauss, who went viral aged 19 with her debut single 1950, a plush but covertly bitter anthem about a complex queer romance. That single, released on Mark Ronson’s Sony imprint Zelig, broke through to the US charts and established Strauss as a pop sensation in waiting.

But the music she released after 1950 – her gorgeous, unburdened 2019 debut album Cheap Queen and its knottier, more rock-inspired 2022 follow-up Hold On Baby – suggested that, perhaps, Strauss was a more interesting and ambitious artist than that “next big thing” tag allowed for. Girl Violence is her first album on the independent Section1; signing with the label, she says, made her realise that the ideas she had about indies were far from the truth. “Artists are told indie labels have no money … that they’re not going to be able to market you, all these things,” she says. “The reality is, that’s complete bullshit. Indie labels are innovative: they can be even more generous with their spending than majors because they are interested in making the best art possible.”

Although she cherishes her new creative freedom, Strauss doesn’t hide the fact that it was hard to experience such huge success very early in her career, only for it to lessen somewhat. “I’m a simple girl – I want to be famous, you know? It was a bit of a punch to the tit, but I don’t regret my decisions or my music at all,” she says. “I refuse to pity myself or feel disappointed for what does commercially well and what doesn’t. Fuck that: this isn’t a race, it’s a marathon, and I want to have a career for the rest of my life. I am a tortoise. You can’t kill me.”

She says that it’s a common fault of the industry that artists carry so much expectation so early in their careers. “For anyone who’s experienced a career high with their first song, that is not a place you want to be. It is tough,” she says. “People then hold you to the standard of something you wrote in your dorm room when you were 18, you know? It’s not realistic. That song blew up completely arbitrarily.”

Strauss has spent the past few years reckoning with the huge upheaval of her early success. Two years ago, she moved back to her home city of New York after a stint in Los Angeles; she enjoyed parts of the west coast, but missed “the diversity of New York; there’s just cool, constant events and happenings. In LA, I was just really excited that people were paying attention to me, so I kind of partied my way through and luckily found some incredible friendships. But [it was] a lot of transience, a lot of me out raging. I don’t know, LA is good for that, if that’s your scene: just going to parties and meeting people and talking and doing coke. I did that for four years, and then I was like: I need daytime friends.”

There was a moment, after moving back to New York, when Strauss felt as if she had fallen out of love with making music, in part because she “stopped thinking about what I actually liked and enjoyed”, and was instead “focused on what was gonna appease the label”. Salvation came in the form of her first acting role: a part in the second season of mystery series Nine Perfect Strangers, which stars Nicole Kidman as a sinister Russian therapist. Filming in Germany for six months, the musician slowly began to feel more energised about art. “I took so much from the acting experience and brought it back into making my record; it taught me to be silly and less precious,” she says. “You have to relinquish so much control when you’re acting: you do your takes, some are shit, some are not. But at the end of the day, you’re not constructing the show, you don’t have the control. And I think a lot of my issues around music were about feeling this sense of control over myself.”

When she got back to New York, Strauss holed up in a Brooklyn studio owned by her recording engineer father, and began to shape Girl Violence without any outside influence from a label. “The only people who were sharing their opinion in the studio was me, and producers Jake [Portrait] and Joe [Pincus], and maybe my dad if he walked in and heard something he didn’t like – but it was mostly the three of us.” She embraced the idea that “all that matters is what I think and what these two guys think. It forced me to make decisions for myself musically.”

Strauss describes the resulting record as a “guidebook” for people trying to understand “different iterations of girl violence”, which may be a side of the lesbian community that many don’t see. “I am baffled by the level of chaos – it’s inspiring. And I’m someone who loves reality TV and drama and The L Word,” she says. Strauss tentatively describes herself as a “reformed” member of the “girl violence community”. “I have been a chaotic lesbian since I was 14 years old. My worst moments? There’s too many to count.”

That reform has been another big part of the past few years for Strauss. “I’ve spent my entire life dating women and having it be hectic and chaotic and painful; I thought love is pain, that’s what I’ve always believed,” she says. She began to feel that she was “horny for being sad”, then began to ask herself: “Why? Can I be horny for being happy? Can I be horny for being safe? For being respected? Can I be horny for being comfortable, instead of equating my horniness to damage and chaos and danger?”

In the end, she found out that “you can be horny for all the good stuff, but it is like an unworking; you have to unwork that in your brain and break down why. That was part of making this record: why do we want what we want as lesbians? Why are we obsessed with being sad?

“I had to really think about how I was presenting myself emotionally. If I was walking through the world needing the validation of a partner to tell me that I’m good, that’s issue number one,” she continues. “And I had to sit down with myself and be like: who am I alone, without anybody? So that was a lot of therapy. And then I guess it was also just looking at myself in the mirror and realising I’ve been dating the same type of girl since I was 14 years old. Never again.”

That self-reflection is borne out in Girl Violence, which adds new depth and complexity to Strauss’s punchy, sneakily virtuosic pop sensibility. Strauss suggests that this new zone, unburdened by commercial expectation, is exactly where she should have been all along. “Commercial success being the standard of success is tough, and I think that it’s really easy to fall into that trap of comparison. I just don’t want to be there: I want to be me, and I want to make the music I make,” she says. “I’m not at a label where they show me pie charts about how well or not well I’m doing: they love the record and we’re having a lot of fun.

“That’s what I wanted. I shouldn’t be emo and weird and comparing myself,” she says. “I’m 26 – I should be having fun.”