Unprecedented adaptation intentions among Canadian private forest owners

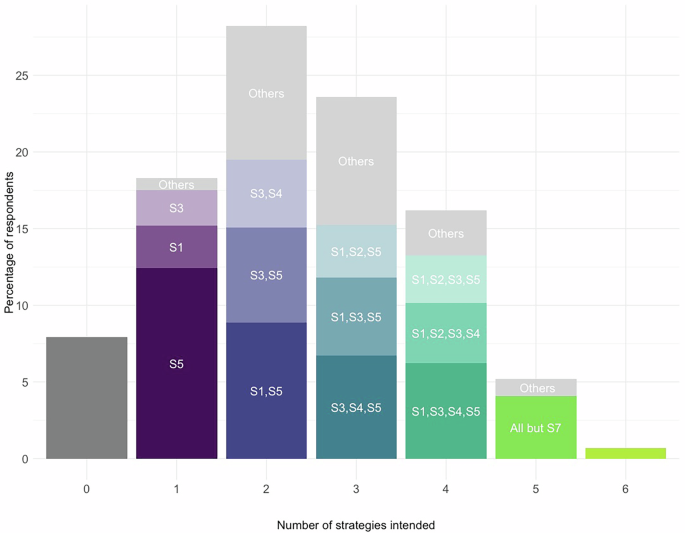

We found that our sample of Canadian forest owners and practitioners exhibit a strong intention to adapt, with 92.1% of the 611 participants willing to adopt at least one adaptation strategy (Fig. 1). Even when excluding ‘laissez-faire’, which could be seen as a passive strategy that requires minimal intervention or resource investment, the adaptation intention rate remains high at 79.6%. For comparison, adaptation intentions among foresters in similar studies worldwide are notably lower, with rates of only 18% in France32 and eastern Oregon10 and 25% to 40% in Sweden28,33. Although adaptation intentions can vary depending on the timeframe for taking action or the wording of the survey questions, these findings represent an unprecedented level of commitment.

Bars represent the percentage of respondents for each strategy (S) they intend to implement (0–6). Each color within the bars indicates a specific combination of strategies (S1–S6), with ‘Others’ representing less common combinations. Total number of respondents: 611. Adaptation strategies: S1, decrease stand density; S2, more frequent logging; S3, species diversification; S4, species replacement; S5, laissez-faire; S6, prescribed burning and fuel load reduction.

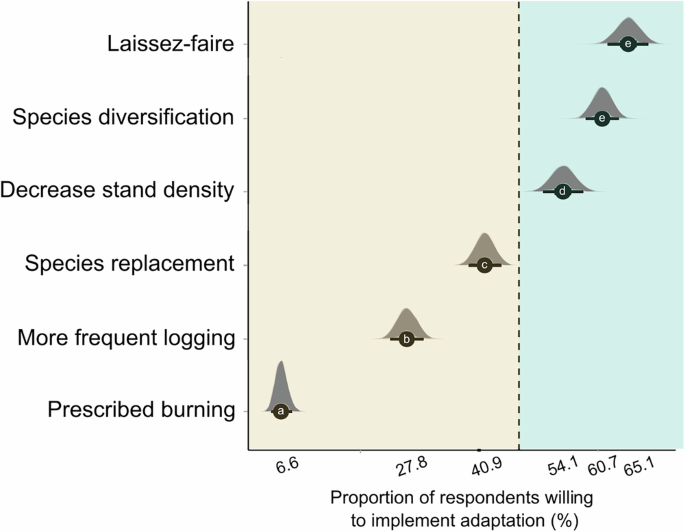

While our sample of private forest owners shows a preference for certain adaptation strategies (Fig. 2), such as decreasing stand density (54.1%), a key finding of this study is the tendency to adopt multiple adaptation strategies, with 73.8% of respondents expressing intentions to implement two or more adaptations simultaneously (Fig. 1).

Most respondents intend to implement multiple strategies, hence strategies are not exclusive. Different letters indicate a posterior probability of ≥0.99 that mean-willingness differs between strategies. Scores to the left of the dashed line indicate a reluctance to adapt, while those to the right indicate a willingness to do so. Black lines denote a 95% equal-tailed credible interval for the mean willingness scores.

At the lower end of the preference spectrum, ‘prescribed burning and fuel reduction’ is the least favored strategy, which aligns with respondents’ motivations related to timber production and the aesthetic value of landscapes, two major forest ecosystem services potentially impacted by this approach (Supplementary Fig. 1). Fire-resilient forestry also requires advanced technical skills and the highest level of coordination among forest owners, but private forest owners are completely—and notably—absent from Canada’s forest fire prevention strategies34.

The most favored strategy, ‘laissez-faire’ (Fig. 2), requires the least effort and reflects a lower level of personal engagement in adaptive management. Yet, laissez-faire should not be confused with management cessation, as 95.5% of respondents intending to implement it are actively managing their forests.

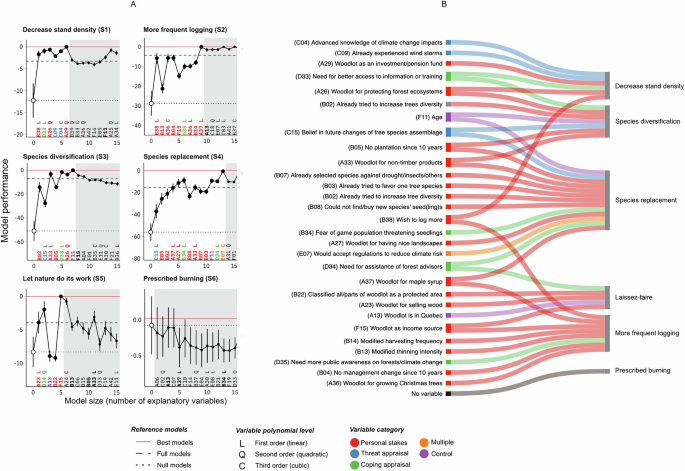

To identify the most influential covariates underlying the intention to adapt, we employed Bayesian predictive projection for variable selection35. This recent method employs cross-validation and takes into account the uncertainty in the posterior predictive distribution to identify a subset of explanatory variables that can sufficiently explain the outcome while avoiding overfitting. For this study, we set up predictive projection such that no other set of explanatory variables (including the full set of all variables) achieves better predictive performance than the subset that was selected (Fig. 3). Out of the 29 covariates selected based on their predictive performance (Fig. 3B), two belong to the category of demographic control variables, specifically private forest owners’ age and location in the province of Quebec (Fig. 4). The remaining covariates relate to personal stakes, threat appraisal, and coping appraisal, aligning directly with the protection motivation theory framework and revealing complex patterns in private forest owners’ willingness to adopt adaptation strategies (Fig. 3). However, the relevance of these covariates strongly differs between adaptation strategies (Fig. 3A): While sufficient predictive performance of the willingness to adopt the species replacement strategy requires 13 different covariates, no covariate contributes substantially to the adoption of prescribed burning. When comparing across multiple strategies, we found that 17 covariates are associated with only one strategy (Fig. 3B), further highlighting the need to distinguish between specific adaptation strategies. This shows that comprehensive adaptation measures (i.e. measures that focus on multiple strategies) are required to focus on a diverse set of underlying motivations and concerns. As foresters’ intention to adapt does not systematically translate into actual adaptive management change36, it is crucial to both understand how key variables can act as levers to increase their willingness to adapt, and identify where current understanding concerning the adaptation willingness and motivation remains limited.

A Model performance is the difference in expected log pointwise predictive density (ELPD) of the best model and the model considered. Vertical lines: standard errors of ELPD estimates. White background highlights covariate contrasts contained in the smallest model that is indistinguishable from the best model, i.e. for which performance is less than one standard error away from the best model. The performance of the best model is indicated by a solid red line. A description of the most influential non-selected variables is provided in Supplementary Tab. 2. B Explanatory variables can be selected for multiple strategies. Among the 29 variables selected based on their predictive performance, 17 of them relate to one strategy only, which underlines the importance of discriminating between adaptations, compared to approaches combining different adaptation actions. ‘Species replacement’ displays the highest complexity, with 13 unique variables selected.

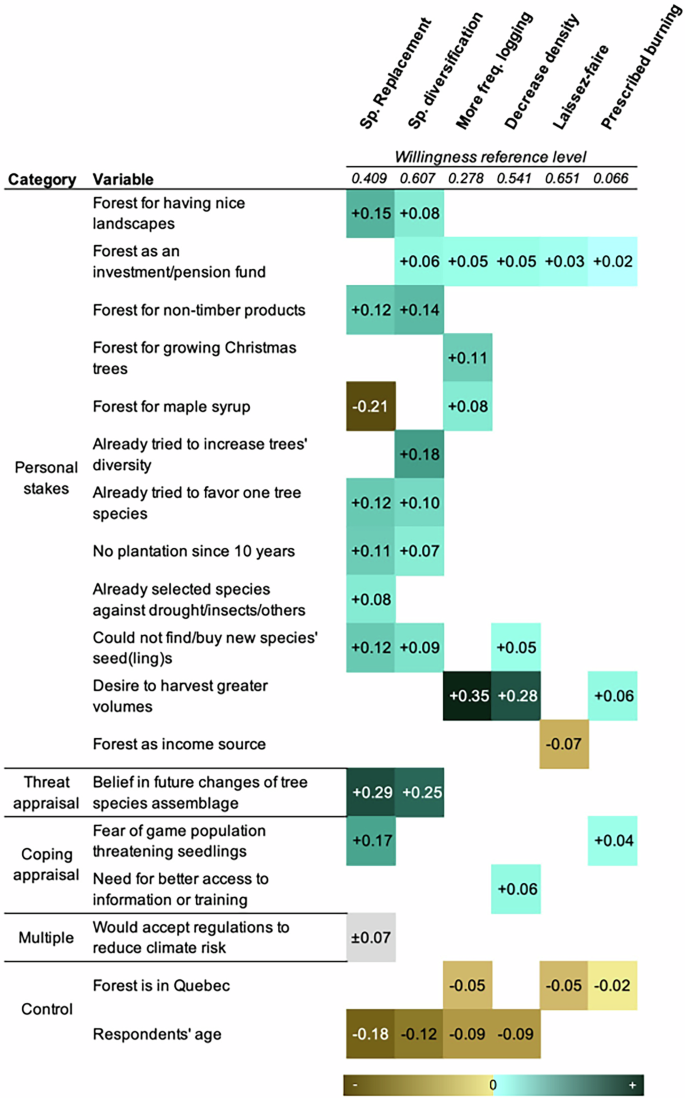

Each cell shows the maximal marginal effect of the corresponding variable on the willingness to adopt an adaptation strategy in the future, with positive effects in shades of green and negative effects in shades of brown. Darker shades indicate stronger positive or negative effects. For categorical covariates, numerical values correspond to the largest difference between factor levels (see Supplementary Table 1 for compared categories and corresponding credible intervals). For instance, NIPF owners for whom producing maple syrup is extremely important show a willingness to replace species that is 21% lower than respondents for whom it is not at all important. Due to correlations between covariates, marginal effects are not additive. Overall effect size decreases from left to right. Effects are shown only if the 0.1 posterior quantile is situated above zero, or the 0.9 quantile is situated below zero.

How well threat appraisal, coping appraisal, and personal stakes may generally contribute towards the explanation of adaptation willingness is expressed by comparing, for each adaptation strategy, the intercept-only null model (which does not include any effects of survey items) to the model that includes the relevant subset of covariates (Fig. 3A). Including survey items based on protection motivation theory substantially increases predictive performance for five adaptation strategies (S1-S5), with performance increasing most strongly for the strategies of species replacement, species diversification, and more frequent logging. Conversely, the willingness to perform prescribed burning is not predicted by any survey items, suggesting that our analytical framework (at least for our sample and as implemented in our survey) does not provide an explanation for this adaptation behavior.

Varying influence of ownership motivations and risk perception on adaptation intention

Designing effective support policies requires a clear understanding of the motivations driving private forest owners to adapt. To that end, we quantified the effects of the entire set of influential covariates (as selected via predictive projection in the previous stage) across all six adaptation strategies simultaneously (Fig. 4). For this purpose, we use a multi-level item-response model37, which accounts for correlations between adaptation actions and covariates38. From this model we calculate marginal effects that express how adaptation willingness changes according to responses given to the survey items (i.e. explanatory variables), conditional on the demographic composition of the sample.

Among all strategies, species replacement represents the most important change in forest operations and can be viewed as a cautious, but proactive approach to adaptive management, with benefits anticipated only in the distant future. The variables influencing species replacement support this perspective, indicating a focus on non-commercial forest ecosystem services (e.g., aesthetic value) and a disinterest in or rejection of commercial services (e.g., Christmas tree production). The active engagement in experimental changes, coupled with the negative impact of private forest owners’ age on species replacement, suggests a commitment to ongoing experimentation in adaptive forest management. A similar set of variables is associated with the ‘species diversification’ strategy, which is clearly oriented toward close-to-nature forestry aimed at preserving forests and enhancing resilience to climate risks5,6.

Strategies such as ‘decreased stand density’ and ‘more frequent logging’ align with traditional forestry practices focused on the production of timber and maple syrup, two lucrative forest ecosystem services. ‘More frequent logging’ may also reflect increased salvage logging following climate disturbances (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, the ‘laissez-faire’ and ‘prescribed burning’ strategies, which are respectively the most and least favored strategies (Fig. 2), are also the least versatile, with the fewest influencing variables and the smallest effect sizes. Laissez-faire is mainly adopted by owners who do not derive income from their forests, while prescribed burning is more strongly rejected in Quebec, possibly due to the lower perceived wildfire risk compared to provinces with a longer history of wildfires15.

Two key variables stand out in our analysis of covariates influencing adaptation intentions: the diversity of ownership motivations and the belief in future changes in tree species composition. First, ownership motivations strongly influence adaptation decisions28,39, which suggests that programs and policies aimed at encouraging private forest owners to adapt to climate change should emphasize the co-benefits of adaptation for a wide range of forest ecosystem services rather than focusing on climate issues alone. No variables related to carbon sequestration are contained in the set of influential variables, which further supports that these aspects do not play an important role in influencing adaptation intentions among private forest owners.

Second, the belief in future changes in tree species composition exerts a major positive influence on proactive adaptation strategies, such as ‘species diversification’ and ‘species replacement’. Consistent with studies in Sweden and Belgium33,40, our findings—representing the first analysis of this kind in North America—suggest that adaptation willingness among private forest owners is more strongly shaped by their subjective perceptions of climate risks than by objective measures of climate vulnerability. This is further supported by the results of the Bayesian variable selection, which found that variables tied to vulnerability, such as property size or proximity to harvest date provided little additional information (Supplementary Tab. 2). This might indicate sensitivity to climate-related disturbances such as wildfires and windstorms.

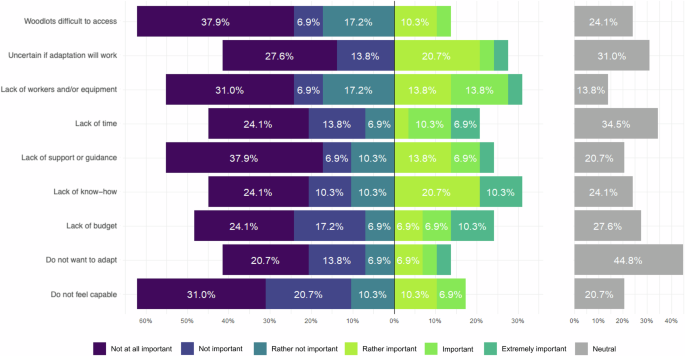

For respondents with no intention to implement adaptive strategies, key barriers include limited know-how, uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of adaptation measures, and insufficient manpower (Fig. 5). Conversely, factors such as enhanced self-efficacy or improved woodlot accessibility do not appear to serve as effective levers for increasing adaptation intentions.

Bars represent the percentage of respondents who rated each reason on a scale from ‘Not at all important’ (dark blue) to ‘Extremely important’ (dark green). The right side of the figure shows the proportion of respondents who rated each reason as ‘Neutral’ (gray). Number of respondents: 30.

Overall, these results indicate that policies aimed at supporting private forest adaptation to climate change should appeal to forest owners’ common but differentiated motivations for owning forests and fully account for threat appraisal as a useful leverage point. Another important insight for policy formulation is that most of the highly influential explanatory variables show constant direction of effects across all adaptation strategies (although at varying degrees of impact) (Fig. 4). This suggests that the design of highly effective policies is indeed possible, targeting multiple strategies simultaneously with little trade-offs between competing options.

Less than one in ten forest regulations or climate programs support private forest adaptation

An important question remains, do current forest policies in Canada encourage private forest owners to implement adaptive management? To evaluate the extent of support provided to private forest owners in their efforts to adapt to climate change, we examined three primary levers of adaptive management in forestry: public regulations, voluntary programs, and sustainable certification systems. In Canada, public authorities have traditionally favored assistance and support programs over imposing laws and regulations, particularly in the context of public forests14. However, regulations do apply to private forests, primarily through provincial legislation41. We identified 100 acts, strategies, voluntary programs, and certification systems relevant to privately owned forests42, but only nine specifically addressed climate change mitigation or adaptation. This variation in public authority involvement, both across and within federal and provincial governments, affects the consistency and effectiveness of climate adaptation policies available to private forest owners.

At the federal level, the Canadian government prioritizes partnerships with the private sector and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) over regulatory approaches43. For example, the ‘2030 Emissions Reduction Plan’ mobilizes funding for climate initiatives across Canada, including specific support for forest owners in Prince Edward Island, where over 85% of forests are privately owned, a marked contrast to the predominantly public forest ownership in the rest of Canada. The Prince Edward Island Woodlot Owners Association, supported by this federal funding, promotes forest biodiversity through a participatory conservation planning tool offering forest tours, information sessions, and the ‘Woodlot Owner of the Year’ award44. This initiative aligns well with one of the key motivations for climate change adaptation identified in our study: an emphasis on non-productive forest ecosystem services (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that such voluntary, incentive-based programs are most effective when combined with regulatory frameworks45, yet none of the eight forestry-related federal acts explicitly addresses climate change adaptation in privately owned forests (Fig. 6). The closest approach to regulation comes through certification systems, such as the Forest Stewardship Council and the Sustainable Forestry Initiative. However, since these certifications primarily apply to private forest owners engaged in commercial logging, they predominantly encourage practices centered on timber production, such as ‘decreased stand density’ and ‘more frequent logging,’ while neglecting other adaptation strategies that respondents in our study favored, such as ‘species diversification’.

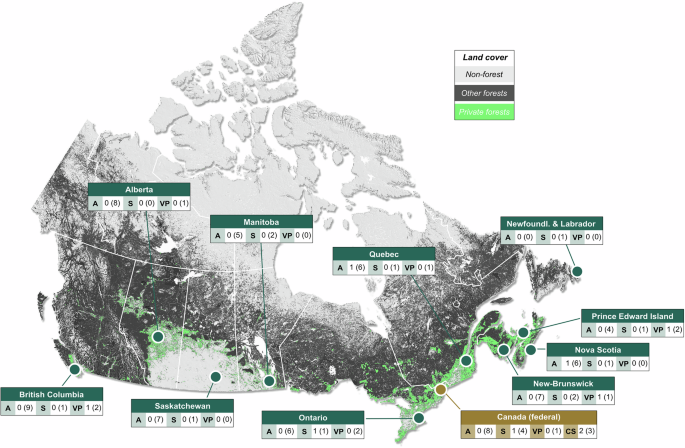

The letters (A, S, V, F) represent different types of policy instruments or support mechanisms – A: Acts regulating forest management, including private forests. S: Strategies initiated by public authorities related to (private) forest management and/or climate change. V: Public voluntary programs supporting private forestry or climate change mitigation or adaptation. F (federal scale): Forestry certification systems. The numbers indicate the count of documents explicitly mentioning the role of private forests in mitigation or adaptation, with the total number of documents shown in parentheses (full dataset available online33). Spatial data on private forest locations is sourced from Stinson (2019)86 under a CC BY 4.0 license. ‘Other forests’ encompass treaty/settlement and Crown forests, Indian and federal reserves, and restricted or protected forested areas.

At the provincial level, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador offer no assistance for private forest owners’ climate change adaptation (Fig. 6). While this may be unsurprising in Newfoundland and Labrador, where private forest ownership is rare, it leaves nearly 3 million hectares of private forests in the Western provinces vulnerable to a wide range of climate change-related risks, from wildfires to pest outbreaks46. In contrast, British Columbia and Quebec have integrated adaptive practices into the management guidelines of their funding programs for timber-oriented private forest operations42, taking the lead in mainstreaming climate change adaptation in private timber production. However, we found no specific funding for private owners interested in non-timber forest ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration or biodiversity conservation.

Most regulations, strategies, and voluntary programs primarily allocate budgets to tax reductions or refunds for forest operations. However, our findings suggest that these funds could be utilized more effectively. Financial incentives alone do not appear to be important drivers of adaptation among private forest owners, as our analysis did not identify them as major motivators (variable ‘Forest as income source’, Fig. 4). For instance, increasing direct funding would likely have only a marginal impact on the small fraction of private forest owners currently unwilling to adapt (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

Instead, technical assistance emerged as a more effective driver of adaptation, consistent with findings from studies in Europe and other regions29,39,47. Redirecting funds toward providing appropriate forest reproductive material (e.g., seeds and seedlings for assisted migration) and protection against browsing damage could better support ‘species replacement’ strategies (Fig. 4). Technical assistance in the form of expert-led field tours could help build private forest owners’ confidence in changing tree species composition and strengthen their capacities to adapt their forests.

While payments for ecosystem services remain popular among public authorities39, public support still predominantly targets timber-oriented adaptation strategies, overlooking opportunities to implement a wider array of strategies on private forests. Encouraging a more diversified approach to adaptation could better equip private forests to meet the challenges posed by climate change, even if such strategies are currently less favored by owners.

Implications for policy formulations

Extreme events, such as the unprecedented wildfire season in Canada in 202348, the extreme drought in central Europe in 201849 or the expected increase in climatic risk to the world forests particularly in southern boreal, dry tropics and central Europe50 underscore the urgent need for climate change adaptation strategies. As most countries have substantial private forest ownership, forest owners constitute an important lever to implement these strategies and ensure the provision of critical ecosystem services, particularly in proximity to more densely populated areas. Yet, our findings reveal a concerning paradox. On the one hand, we found one of the highest recorded intentions to adapt among private forest owners compared to the existing literature on forest management, along with a strong preference for implementing multiple adaptation strategies concurrently. On the other hand, we observed a mismatch in government efforts, as federal and provincial authorities often prioritize adaptation goals focused on productivity at the expense of other essential ecosystem services provided by private forests. This suggests an urgent and crucial need to reevaluate traditional policy approaches, such as tax reductions and forest operation reimbursements, which, while necessary, are insufficient to decidedly increase adaptation intentions. Our results indicate that the most effective support for private forest owners lies in providing detailed information on local climate change impacts and emphasizing the positive outcomes of adaptation for environmental and personal values rather than solely focusing on climate risk reduction. Despite limitations in the representativeness of our sample, these findings align with several articles in different national contexts emphasizing the importance of promoting voluntary adoption of adaptive forestry practices, e.g. ref. 51, alongside appropriately balanced regulatory approaches14,52. This international perspective offers a complementary framework for considering how supporting the adaptation of non-industrial private forests (NIPFs) to climate change benefits national objectives. Empirical insights from African53 and European54 contexts demonstrate that public support for private forests can simultaneously advance social and environmental objectives (e.g., poverty reduction, climate mitigation). This dynamic is of clear relevance to Canada’s efforts to achieve the targets of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Offering technical assistance and capacity-building support on key aspects of adaptive practices implementation could complement this approach, supporting multiple adaptation strategies simultaneously, as outlined in European contexts32,55,56. Had it been feasible, a fully representative sample of NIPF owners could also have brought feedback on this point from voluntary programs led in British Columbia and New-Brunswick. Our study was also somewhat limited by the small number of private forest owners unwilling to adapt, which prevented a robust statistical analysis of their socio-economic profiles—insights that could help refine public policies and programs targeting this specific audience. In this regard, we must acknowledge the pioneering training provided by the University of British Columbia to forest experts aimed at enhancing climate change readiness among private sector consultants13.

Our findings should also be assessed in light of adaptive forest management approaches that aim to reconcile biodiversity and climate goals. The strategies most favored by private forest owners align with the climate-smart forestry and functional network approaches5,6. For instance, the ‘laissez-faire’ strategy can lead to the successional development of old-growth forests, which exhibit unique structural attributes that enhance species diversification and support multiple ecosystem services57,58. This strategy reflects the motivations of these managers to allow forests to develop on their own, often driven by high uncertainty about the effectiveness of the strategies and a preference for less costly and time-consuming options20. Nevertheless, there are concerns regarding the ecological adaptive capacity of these forests, which may be outpaced by the rapidity of climate change59. While increasing species diversity could mitigate risks and enhance ecosystem stability, it may also entail economic costs for the forestry sector and pose risks of habitat losses for certain species60.

Despite our best efforts, the study’s conclusions should be interpreted in light of its methodological limitations. In particular, representativeness biases are inherently difficult to avoid, especially in Canada, where data on non-industrial private forest owners remain fragmented and incomplete. This situation could be addressed through the development of comprehensive lists of forest landowners in the country, for instance by the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers. Although socio-economic comparisons were constrained by limited reference data, the sample appeared reasonably representative on key variables, with higher education levels and larger landholdings aligning with established patterns in voluntary survey participation. Nevertheless, the study makes a novel contribution by drawing on the protection motivation theory to connect individual-level determinants with broader institutional dynamics. It reinforces the idea that adaptation should not rest solely on landowners, but must also involve governments and institutions61.

The lack of adequate institutional support for private forest owners, despite their willingness to adapt, represents a major opportunity not only for Canada but also for forest management globally. Effective governance and coordination among forest managers are critical to successfully implementing adaptation strategies, such as those emphasized in climate-smart forestry and functional diversity approaches. Involving private forest owners in participatory policy-making could shed light on practical barriers to implementation, such as access to diversified tree seeds, including setting up nurseries for seed production and supply. Private forest owners account for a substantial share of forested land in many countries8, are majorly found close to where people live, and we expect that, similarly to Canada, their high levels of motivation to pursue adaptive practices could create the potential for a rapidly implementable forest network that could serve as a long-term social-ecological adaptation observatory and testing ground for possible implementation in public forests worldwide. This presents a unique opportunity for a global body like the United Nations Forum on Forests Council of Forest Ministers to recommend and pilot programs offering local climate impact information, along with technical assistance and expert guidance.