As climate change intensifies, companies and countries are attempting to build new low-carbon supply chains. From electric vehicles to solar panels and wind turbines, these technologies require vast amounts of critical minerals.

These are commodities such as cobalt, lithium and nickel, and also include a smaller set of 17 rare earth elements like dysprosium, neodymium, praseodymium and terbium.

Canada’s federal government, and provincial officials in Ontario, have pledged some of the biggest public subsidies to private companies in a generation — more than $43 billion — to create this new supply chain.

Plans for new mines in Northern Ontario’s “Ring of Fire” to extract critical minerals parallel billions in production subsidies to EV producers and related manufacturers in the province’s southern manufacturing heartland.

The idea is to supply southern factories with northern minerals. Instead of only exporting unrefined primary commodities like oil, copper or lumber, Canadian industry would also export high-value, renewable technology-related products.

In addition to promises around jobs, innovative industries and fighting climate change, politicians, business executives and military analysts frame the country’s critical minerals strategy around countering China’s dominance.

However, our new study identified several challenges to subsidizing supply chain integration in Canada.

Based on 20 interviews with government officials and industry leaders in Ontario’s critical minerals sector, and a review of existing literature, we identified challenges including: opposition to new mining and infrastructure projects, particularly from some Indigenous communities; some policymakers lacking understanding of the complexity of supply chains; slowing global EV demand and regional trade barriers at a time of uncertainty for the sector.

Processing: The weak link

First, there is a weak link in the planned supply chain: processing. Policymakers and average Canadian can picture a mine or an EV factory, business leaders said.

Understanding how to separate terbium, a rare earth element used to make stronger alloys for EVs, from mined stock is a more difficult process conducted in unassuming industrial parks. It doesn’t necessarily excite the public imagination.

(Natural Resources Canada/Eric Leinberger), CC BY-NC

This is not merely complicated chemistry. Processing and refining critical minerals is where China dominates, controlling about 90 per cent of the industry. Under the current plan, even if mines are built in Northern Ontario, the minerals would likely be sent to China to be processed and then shipped back, leaving manufacturers dependent on the Chinese.

As one long-time chemical processing executive said: “Governments have convoluted the resource sector, the stuff in the ground, the product in the end (EVs and related technologies) and forgotten this middle section” before adding “infrastructure isn’t sexy and [processing facilities] are weirdo infrastructure nobody sees.”

Companies in Canada or the United States, the executive said, don’t want to pay a premium for rare earths processed in Canada. China can do the work more cheaply.

Investments suspended and delayed

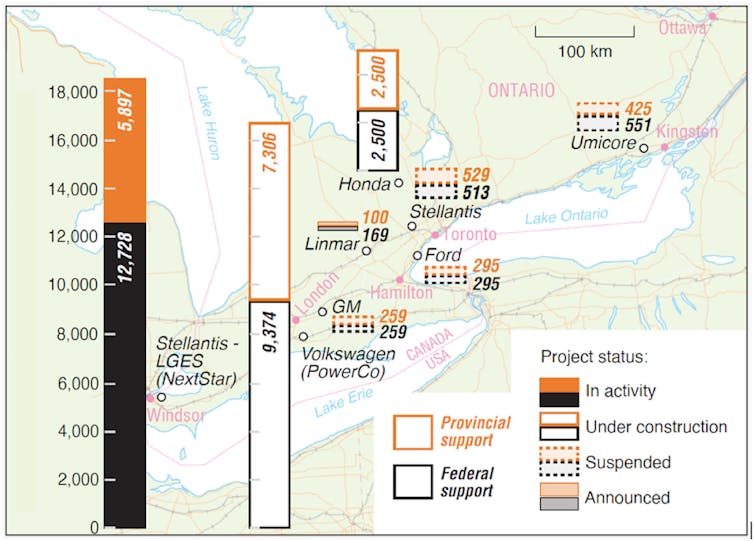

Second, many high-profile manufacturing projects have been shelved or suspended, despite billions in promised subsidies. Of eight major EV manufacturing plants in Ontario selected to receive a combined $43.6 billion in subsidies, five have suspended or delayed their activities, including the European firm Umicore’s planned $2.7 billion battery plant near Kingston, Stellantis’ EV jeep production in Brampton and GM’s EV van plant in Ingersoll, which halted then reduced production earlier this year.

Subsidies promised to these firms are far higher than what the companies themselves pledged to invest. Our analysis suggests pledged public subsidies for the eight renewable manufacturing projects, including money from the federal government and Ontario, are more than 13 per cent higher than what the companies themselves promised to spend from their own coffers.

This doesn’t seem like a good use of the public purse. Subsidies can certainly help spur growth in new industries if leveraged effectively: South Korea and Taiwan’s development from the 1960s illustrates this. But spending more public money than private companies themselves are willing to invest does not seem wise in the current trade climate, especially considering government deficits and the costs of financing them given high interest rates.

In fairness to provincial and federal officials, much of the pledged money has not left the treasury. A substantial portion of the promised funds are production subsidies for each car or battery produced.

The cancelled projects, and uncertainty over access to U.S. markets and EV sales in North America, are making companies skittish, subsidies be damned. Canada this month suspended its own planned EV mandate which would have required 20 per cent of all new vehicles sold here to be electric by next year.

(Author provided/Eric Leinberger), CC BY-NC

Subsidies and the new mercantalism

Recent problems in the EV industry notwithstanding, the broader subsidy race to build out renewable energy supply chains, and the geopolitical scramble to control critical minerals, has a distinctly 19th century, neo-mercantalist vibe.

Hearkening back to the days of the British East India Company and gunboat diplomacy, corporations are working arm-in-arm with governments to advance commercial and military objectives. U.S. President Donald Trump has demanded Ukraine give American companies preferential access to the country’s vast critical minerals deposits in exchange for continued military aid amid the war with Russia.

China currently mines roughly 70 per cent of the world’s rare Earth elements, according to Canadian government data. More importantly, it processes nearly 90 per cent of the strategic commodities and also holds near processing monopolies for graphite (95 per cent), manganese (91 per cent), and cobalt (78 per cent).

China is not afraid to weaponize its control of rare earths, limiting access for U.S. companies following Trump’s tariff threats or temporarily cutting them off to Japan following a dispute over fishing and territorial rights in 2010.

“If China embargoed rare earths right now, that would put us out of business,” said one senior Ontario government official we interviewed. “They are a critical part of the supply chain.”

Against that backdrop, and threats against Canada from the Trump government, there is value in building coherent public policy around critical minerals.

However, following billions in pledged subsidies delivering mixed results, federal and provincial governments need to focus their limited financial firepower on what’s actually achievable. Developing the means to refine and process critical minerals extracted here would be a good first step.