Invisible plastic fragments from common tableware are turning up in semen; now, researchers reveal how nanoscale particles may quietly sabotage male reproductive biology through cellular stress and self-destruction pathways.

Study:…

Invisible plastic fragments from common tableware are turning up in semen; now, researchers reveal how nanoscale particles may quietly sabotage male reproductive biology through cellular stress and self-destruction pathways.

Study:…

South Korea is nearing a decision on whether to allow Google and Apple to export high-resolution geographic map data to servers outside the country. The detailed maps, which use a 1:5,000 scale, would show streets, buildings, and alleyways in…

A groundbreaking international study changes the view that exposure to the toxic metal lead is largely a post-industrial phenomenon. The research reveals that our human ancestors were periodically exposed to lead for over two…

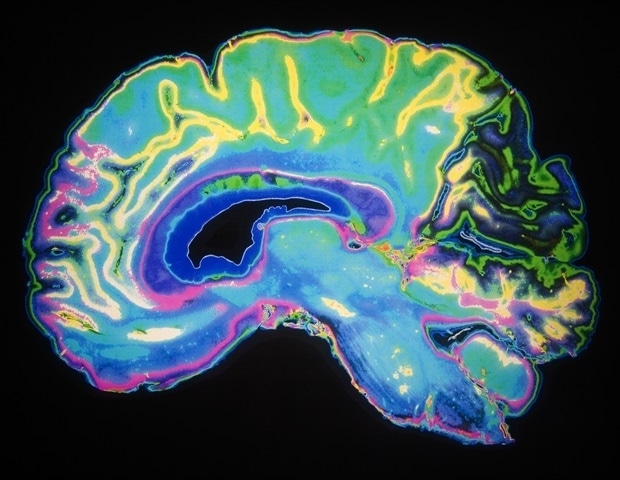

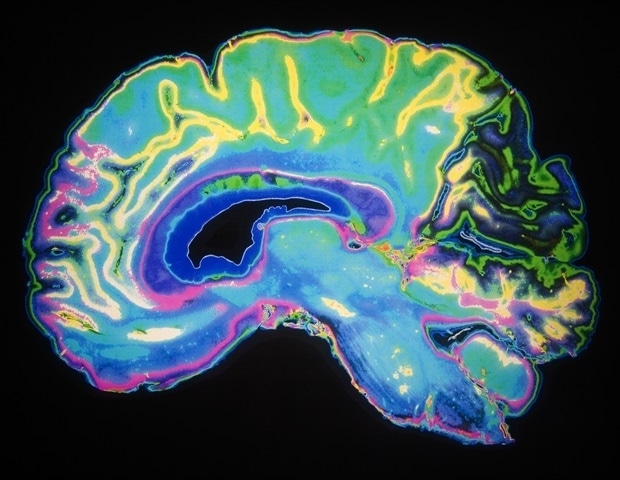

Why are we able to recall only some of our past experiences? A new study led by Jun Nagai at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Japan has an answer. Surprisingly, it turns out that the brain cells responsible for stabilizing…

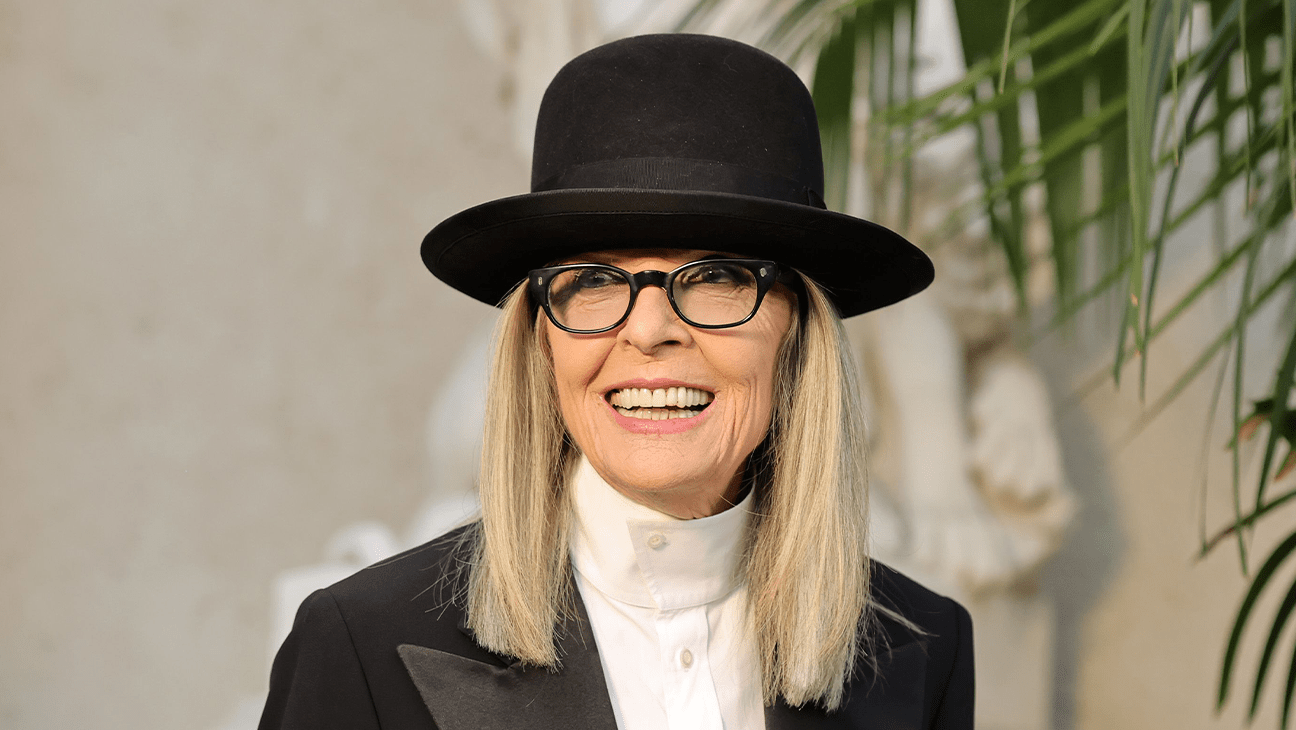

Diane Keaton‘s cause of death has been revealed days after the Hollywood icon died at age 79.

The Oscar winner’s family told People magazine that she died from pneumonia on Oct. 11. “The Keaton family are very grateful for the…

By Tomi Kilgore

Air carrier’s stock falls as revenue extends its streak of misses, to offset another profit beat

United Airlines expects strong travel demand leading to record revenue in the holiday quarter, but the stock fell after third-quarter revenue missed expectations, again.

Shares of United Airlines Holdings Inc. fell in after-hours trading Wednesday, after the air carrier reported revenue that missed expectations for a third straight quarter, which took the shine off an upbeat travel outlook over the holidays.

The revenue miss comes even after profits continued to beat Wall Street’s projections, and after the company said it was “thriving” despite uncertainties about the economy, thanks to strong demand from flyers seeking premium services and from members of its frequent-flyer programs.

United’s stock (UAL) declined 1.9% in Wednesday’s after-hours session, after closing the regular session up 0.9% at a four-week high.

Net income for the quarter to Sept. 30 slipped 1.7% to $949 million, while adjusted earnings per share, which excludes nonrecurring items, of $2.78 beat the FactSet consensus of $2.65. That marked the 13th straight quarter United had beat bottom-line expectations.

Meanwhile, total revenue rose 2.6% from the same period a year ago to $15.23 billion, but that was below the average analyst revenue estimate compiled by FactSet of $15.33 billion.

Revenue from premium seats increased 6% and revenue from its loyalty program members grew 9%, to outpace revenue growth from basic economy seating of 4%.

Passenger revenue, which excludes cargo and other revenue, rose 1.9% to $13.82 billion, with domestic revenue increasing 3.1%.

The company said the growth momentum, particularly in premium and loyalty flyers, has continued into the current fourth quarter. As a result, United now expects the fourth quarter to have “the highest total operating revenue for a single quarter in company history.”

United’s positive outlook comes a week after rival Delta Air Lines Inc. (DAL) made similar comments about its outlook for the rest of the year, with sales trends accelerating, particularly among premium flyers.

United’s stock has gained 7.2% in 2025 through Wednesday, while the U.S. Global Jets ETF JETS has edged up 0.7% and the S&P 500 index SPX has advanced 13.4%.

-Tomi Kilgore

This content was created by MarketWatch, which is operated by Dow Jones & Co. MarketWatch is published independently from Dow Jones Newswires and The Wall Street Journal.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

10-15-25 2017ET

Copyright (c) 2025 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

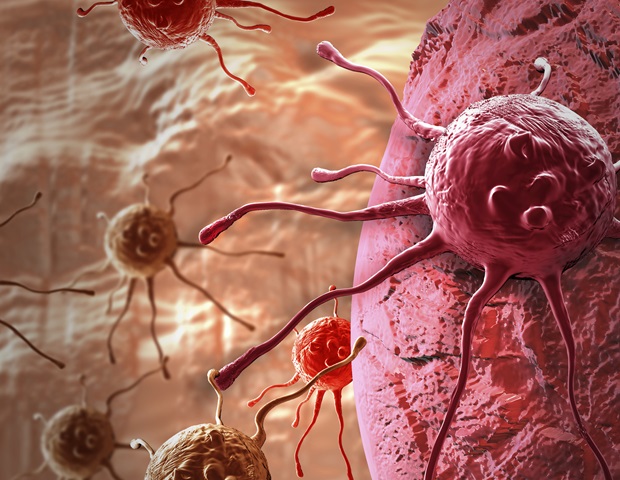

Lung cancer screening might be the best-kept secret in health care today. Only about 16 percent of those who are eligible in the U.S. get screened for lung cancer, but a study coming out in NEJM Catalyst on Wednesday provides a…

Appointment opens a new chapter in Apollo’s next phase of growth: expanding capital, wealth and retirement solutions across the region

TOKYO and NEW YORK, Oct. 15, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) — Apollo (NYSE: APO) today announced Mr. Eiji Ueda has been named a Partner and Head of Asia Pacific, succeeding Matt Michelini. Michelini, who has spearheaded Apollo’s rapid expansion across the region since his appointment in 2022, will remain in region to oversee Ueda’s transition before assuming broader leadership responsibilities with the firm next year.

Ueda joins Apollo with demonstrated investment expertise and a nuanced understanding of Asia’s evolving needs. He most recently served as Chief Investment Officer of Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), one of the largest institutional investors globally, where he led a strategic portfolio restructuring to deliver positive results through unprecedented market volatility. Previously, he spent nearly three decades with Goldman Sachs holding positions across major financial centres, including Head of Fixed Income Trading and Head of Fixed Income, Currency and Commodities (FICC) in Tokyo as well as Co-Head of Securities, Asia, based in Hong Kong. He also served as a member of Goldman’s Asia Pacific Management Committee, Firmwide Risk Committee and Chair of the Asia Pacific Risk Committee.

“Asia Pacific is key to Apollo’s next chapter of growth,” said Jim Zelter, President of Apollo. “Fundamental shifts in the region’s economies are creating a surge in demand for not just capital, but for more integrated financial solutions across capital, wealth and retirement. We believe Apollo’s full platform, including our origination ecosystem, is well-positioned to meet these needs. Ueda’s track record of innovation, disciplined risk oversight and cross-asset management will enable us to continue scaling with conviction and understanding of local markets.”

“Apollo is bringing something new to Asia: beyond global investment expertise underpinned by local sensitivity, the firm goes further to deliver wealth and retirement solutions others may find hard to build,” said Ueda. “Asia’s demographics, savings base and capital gaps present one of the most compelling growth arcs in the world. I am excited to join the team and help position Apollo as the partner of choice across that entire continuum.”

“It has been a privilege to lead Apollo’s Asia growth over the past several years,” said Matt Michelini. “Together, we have assembled an incredibly talented team, built out our core capabilities in credit, hybrid capital, wealth and retirement solutions and established strategic partnerships that are unlocking new opportunities the region needs. Ueda’s appointment signals both continuity and evolution, and I look forward to partnering with him as we enter Apollo’s next stage of growth.”

Since 2022, Apollo’s Asia Pacific business has grown from 80 to over 150 professionals, spanning the region to deliver the firm’s leading capabilities across private investment grade credit, hybrid capital, wealth, retirement and insurance. Apollo’s approach in Asia reflects its broader strategy: long-term focused, structurally flexible and built on partnership and alignment. The firm has originated over $11 billion over the past twelve months — more than ten times the amount originated in 2020. Apollo’s retirement services business Athene has grown rapidly, reinsuring close to $19 billion in policy value to date. With strategic partnerships in Australia, Japan, Greater China and Korea, the firm has matched global scale to regional opportunities in support of growing demand for private market access and reliable income solutions.

About Apollo

Apollo is a high-growth, global alternative asset manager. In our asset management business, we seek to provide our clients excess return at every point along the risk-reward spectrum from investment grade credit to private equity. For more than three decades, our investing expertise across our fully integrated platform has served the financial return needs of our clients and provided businesses with innovative capital solutions for growth. Through Athene, our retirement services business, we specialize in helping clients achieve financial security by providing a suite of retirement savings products and acting as a solutions provider to institutions. Our patient, creative, and knowledgeable approach to investing aligns our clients, businesses we invest in, our employees, and the communities we impact, to expand opportunity and achieve positive outcomes. As of June 30, 2025, Apollo had approximately $840 billion of assets under management. To learn more, please visit www.apollo.com.

Forward-Looking Statements

In this press release, references to “Apollo,” “we,” “us,” “our” and the “Company” refer collectively to Apollo Global Management, Inc. and its subsidiaries, or as the context may otherwise require. This press release may contain forward-looking statements that are within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. These statements include, but are not limited to, discussions related to Apollo’s expectations regarding the performance of its business, its liquidity and capital resources and other non-historical statements. These forward-looking statements are based on management’s beliefs, as well as assumptions made by, and information currently available to, management. When used in this press release, the words “believe,” “anticipate,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Although management believes that the expectations reflected in these forward-looking statements are reasonable, it can give no assurance that these expectations will prove to have been correct. These statements are subject to certain risks, uncertainties and assumptions. We believe these factors include but are not limited to those described under the section entitled “Risk Factors” in our annual report on Form 10-K filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) on February 24, 2025, as such factors may be updated from time to time in our periodic filings with the SEC, which are accessible on the SEC’s website at www.sec.gov. We undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future developments or otherwise, except as required by applicable law. This press release does not constitute an offer of any Apollo fund.

Contacts

Noah Gunn

Global Head of Investor Relations

Apollo Global Management, Inc.

(212) 822-0540

IR@apollo.com

Joanna Rose

Global Head of Corporate Communications

Apollo Global Management, Inc.

(212) 822-0491

Communications@apollo.com

Australia’s Ariarne Titmus will not return to the pool following a year-long hiatus from competitive swimming.

The 25-year-old Tasmanian middle distance specialist announced her retirement on Wednesday (15 October), penning a heartfelt social…

Drug Topics A study shows young adults with 3 or more COVID-19 vaccine doses experience fewer symptoms, emphasizing vaccination’s critical role in public health.

Link to study here

Young…