- Researchers recently analyzed an ancient Arabic poem praising Saladin that contains a reference to a new star, now identified as a supernova seen in 1181.

- The poem is from sometime between December 1181 and May 1182, aligning with Chinese and Japanese observations of the supernova.

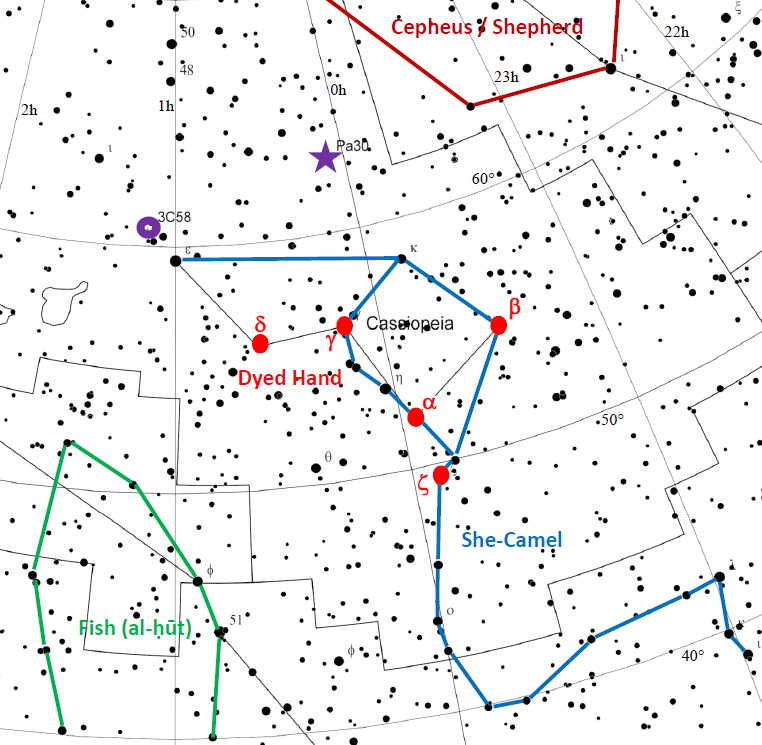

- This discovery helps confirm the timing, brightness and location of the supernova, likely linked to the nebula Pa 30 in Cassiopeia.

Researchers find Supernova 1181 reference in an old poem

Supernovas look like stars that suddenly appear in the sky. But they’re actually explosions of massive stars at the ends of their lives, shining brilliantly then gradually fading over time. If a supernova occurs within several thousand light-years of us, it could be bright enough to view with the unaided eye. Supernovas are rare, but historical writings have documented a few of them. One was Supernova 1181, which Chinese and Japanese observers recorded. It first appeared in early August 1181, and by February 1182 it had faded from view. On September 4, 2025, scientists said they’ve discovered new written evidence of Supernova 1181, in the work of an Arabic poet, providing more clues about this enigmatic object.

Ibn Sana’ al-Mulk, a well-respected secretary in the Saladin Empire, wrote the poem featuring the supernova. The author penned it in a style called praise poetry, where the poem lavished generous accolades on Saladin, a powerful military leader and politician. Saladin dominated the Middle East during the 12th century, founding the Ayyubid Dynasty and becoming the first sultan of Egypt and Syria.

The researchers published their findings as a preprint in arXiv on September 4, 2025.

Excerpt of a poem by Ibn Sana’ al-Mulk, in praise of Saladin

Below is the section of the poem by Ibn Sana’ al-Mulk referencing the supernova. J. G. Fischer, at the University of Münster’s Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies in Germany, translated it to English.

The verses below are numbered as they appeared in the preprint, as are comments in brackets.

1. I see how everything on the surface of the Earth has increased in number thanks to your justice; now even the stars [anjum] in the sky have increased in number.

2. [The sky] adorned itself with a star [najm]; nay, it smiled through it, because whoever is delighted by a delightful thing smiles.

3. The Dyed Hand [Cassiopeia] used to be unadorned, but when time became adorned because of you, it put on a (signet) ring.

4. Let not the sky’s hand boast of its star, since so many of your noble deeds shine bright like stars.

5. Your stars have never perplexed any astronomer, while this star has perplexed astronomers and astrologers alike.

6. They are in disagreement over it and stammering; but never have we seen anyone stammer when it came to your high station.

7. We can see how you buried a spear on the horizon, leaving its butt behind and throwing its sharp head.

8. But this is just an error due to my fantasy, and a mistake due to my illusions.

9. [In reality] the star is your father, who left his abode out of longing for you and in order to greet you.

10. The stars’ spheres come to your aid and their meteors are an army with which you destroy mighty armies.

11. How often did Arcturus brandish its spear to strike your enemy until it was almost shattered to pieces!

12. Those who rule on the surface of the earth cannot be compared to one destined to rule the lights of the sky.

13. You rose until it was impossible to rise any further; you progressed until it was impossible to progress any further.

14. Fate does not allow what you refuse to happen, and neither does it refuse what you allow.

15. May the stars sacrifice themselves for the son of Ayyub [Saladin], for they are his servants and thereby sacrifice themselves for the master,

16. who forever stands above them in eminence and forever is a better guide than they are.

17. So do not put him on the same level as other princes, for he is the greatest of them on earth and the most elevated of them in the sky.

The poem was initially not dated correctly

The poem itself does not have a date. Previously, some scholars thought the new star was a planetary conjunction in 1186, which ancient astrologers described. That event is one in which planets may have appeared close enough to look like a bright new object. It’s also possible that introductory remarks in the manuscript, not written by Ibn Sana’ al-Mulk, confused the object for a comet.

In this new study, the researchers analyzed the entire poem to better constrain the timeframe for when it was first recited.

In the last three verses, the poem also praised Saladin’s brother, Saphadin. Therefore, the researchers think the poem was meant to be recited when Saladin and Saphadin were present at an event together. In addition, other verses mention Egypt. According to historical records, Saladin and Saphadin were in Egypt at the same time between January 1181 and May 1182.

Moreover, another section of the poem mentions how Saladin’s soldiers protected Islam’s holy sites from destruction. The researchers think this refers to a Crusader attack on Tabuk in Saudi Arabia, which Saladin repelled in December 1181.

Therefore, the poem was recited sometime between December 1181 and May 1182.

What they learned about Supernova 1181 from the poem

Historical accounts of supernovas are important. Ancient records of a supernova establish its exact age. The duration of its visibility helps astronomers characterize the supernova. Furthermore, a reliable estimate of its peak brightness may help determine its distance. And it enables modern-day astronomers to do detailed follow-ups with telescopes.

Was the object in the poem a supernova? In the poem, the word najm appears several times. It was a term that other Arabic writings used for sightings of transient, stationary, starlike objects, such as supernovas in 1006, 1572 and 1604.

Furthermore, Chinese stargazers observed Supernova 1181 from August 6, 1181, to February 6, 1182, a total of 185 days. The poem about Saladin was recited sometime between December 1181 and May 1182, which overlaps with Chinese and Japanese observations.

The poem also confirmed the supernova’s location. It appeared in the Arabic constellation of the Henna-dyed Hand, a pattern that includes the five brightest stars in Cassiopeia. The signet ring in the poem suggests that the new star was brighter than those stars, including Alpha Cassiopeia, which has a visual magnitude of 2.25. When it faded from view, it was about 5th or 6th magnitude, the limit of what the human eye can see.

Where in Cassiopeia was the supernova?

There are different types of supernovas, defined by their spectral signature. Some are caused by runaway nuclear fusion in a white dwarf (called type Ia). Others explode due to the collapse of a massive star’s core (Types Ib and Ic, Type II).

Telescope observations have revealed two supernova remnants in Cassiopeia.

Astronomers once thought that 3C 58 was the remnant of Supernova 1181. It was a core collapse supernova that now has a central pulsar. However, recent studies have determined it is between 3,000 to 5,000 years old, much older than Supernova 1181, seen 844 years ago.

There’s also a nebula called Pa 30, about 10,100 light-years away. It’s the remnant of a Type 1ax supernova, a rare subtype of Ia. Moreover, astronomers said it exploded about 1,000 years ago. That places it much closer in age to Supernova 1181, and it appears to be the most likely remnant of it.

A star map of the area mentioned in the poem

Bottom line: Researchers discovered new evidence of Supernova 1181 in an ancient Arabic poem praising the 12th century Middle East military leader and politician Saladin.

Source: New Arabic records from Cairo on supernovae 1181 and 1006

Read more: New type of supernova, as a black hole triggers a star explosion