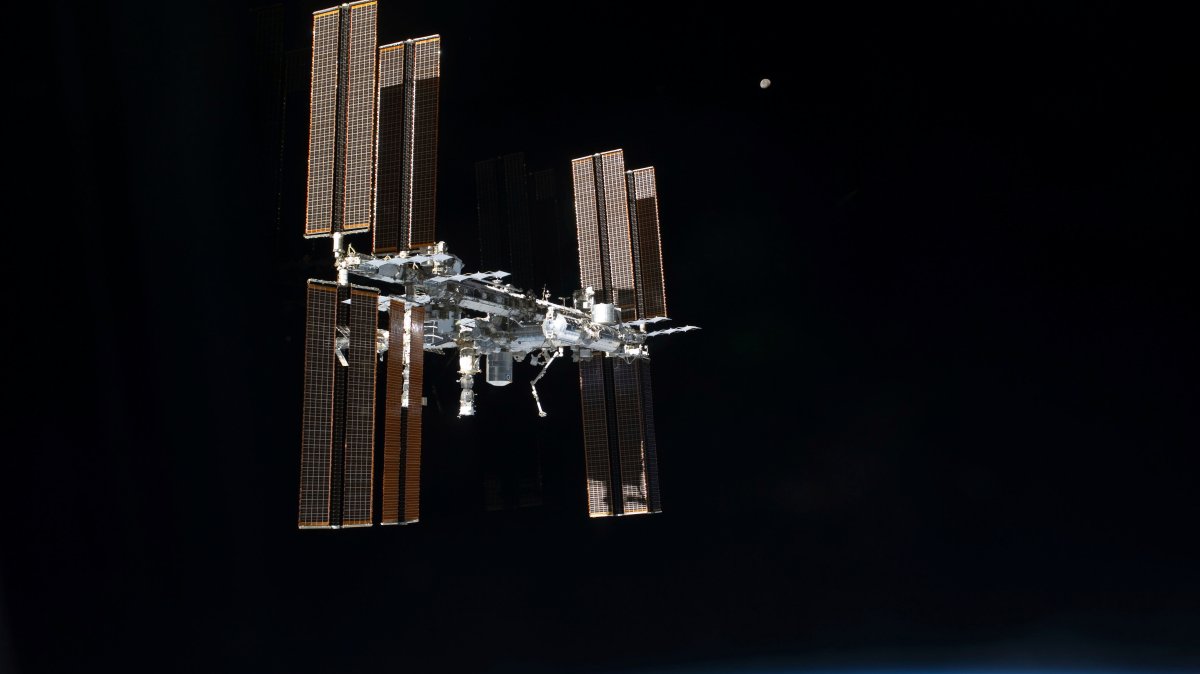

In a rare move, NASA is cutting a mission aboard the International Space Station (ISS) short after an astronaut had a medical issue.

The space agency said Thursday the U.S.-Japanese-Russian crew of four will return to Earth…

In a rare move, NASA is cutting a mission aboard the International Space Station (ISS) short after an astronaut had a medical issue.

The space agency said Thursday the U.S.-Japanese-Russian crew of four will return to Earth…