This article picked by a teacher with suggested questions is part of the Financial Times free schools access programme. Details/registration here.

Read all our psychology class picks.

Specification:

This is an opinion article written in an informal manner, but nonetheless has a serious question at its heart.

Click the link below to read the article and then answer the questions:

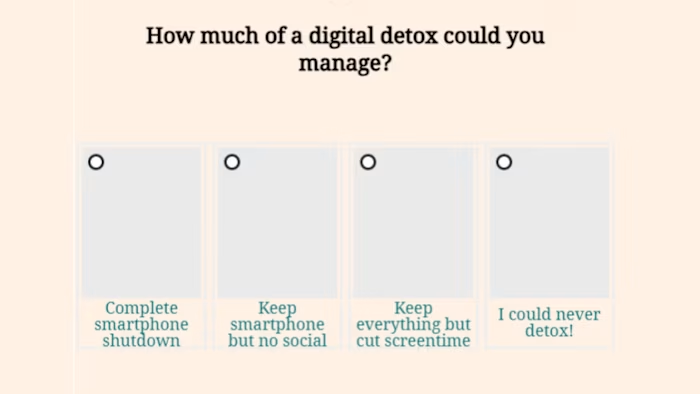

Is it time for a digital detox?

-

The author gives two reasons why a digital detox in the new year is a good idea. What are they?

-

Give one quote from the first two paragraphs that shows he is only half serious about his suggestion

-

What justification does the author give for not recommending a full digital detox?

-

He writes about the dangers of social media, especially TikTok. To what extent do his beliefs about social media provide support or undermine his argument for a digital detox?

-

In psychology, one of the relevant concepts is bias. Identify some example of bias in this article

-

Click on the following links:

Tackling social media’s ‘monster’ problem

Australian users flock to new platforms after social media ban for under-16s

Use the material from these articles and the original to construct a one paragraph argument either for or against banning social media for those under 16 years old

Laura Swash, Inthinking/thinkIB