The world dedicates a Poland-sized area of land to liquid biofuels. Is there a more efficient way to generate energy?

Electric vehicles might be promoted as the key technological solution for low-carbon transport today, but they weren’t always the obvious option. Back in the early 2000s, it was biofuels.1 Rather than extracting and burning oil, we could grow crops like cereals and sugarcane, and turn them into viable fuels.

While we might expect biofuels to be a solution of the past due to the cost-competitiveness and rise of electric cars, the world produces more biofuels than ever. And this rise is expected to continue.

In this article, we give a sense of perspective on how much land is used to produce biofuels, and what the potential of that land could be if we used it for other forms of energy. We’ll focus on what would happen if we used that land for solar panels, and then how many electric vehicles could be powered as a result.

We’ll mostly focus on road transport, as that is where 99% of biofuels are currently used. The world generates small amounts of “biojet fuel” — used in aviation — but this accounts for only 1% of the total.2 While aviation biofuels will increase in the coming years, in the near-to-medium-term, they’ll still be small compared to fuel for cars and trucks. By 2028, the IEA projects that aviation might consume around 2% of global biofuels.

To be clear: we’re not proposing that we should replace all biofuel land with solar panels. There are many ways we could utilise this land, whether for food production, some biofuel production, or rewilding. Maybe some combination of all of the above. But to make informed decisions about how to use our land effectively, we need to get a perspective on the potential of each option. That’s what we aim to do here for solar power and electrified transport.

For this analysis, we draw on a range of sources and, at times, produce our own estimates. We’ve written a full methodological document that explains our assumptions and guides you through each calculation.

Before we get into the calculations, it’s worth a quick overview of where biofuels are produced today, and what their impacts are.

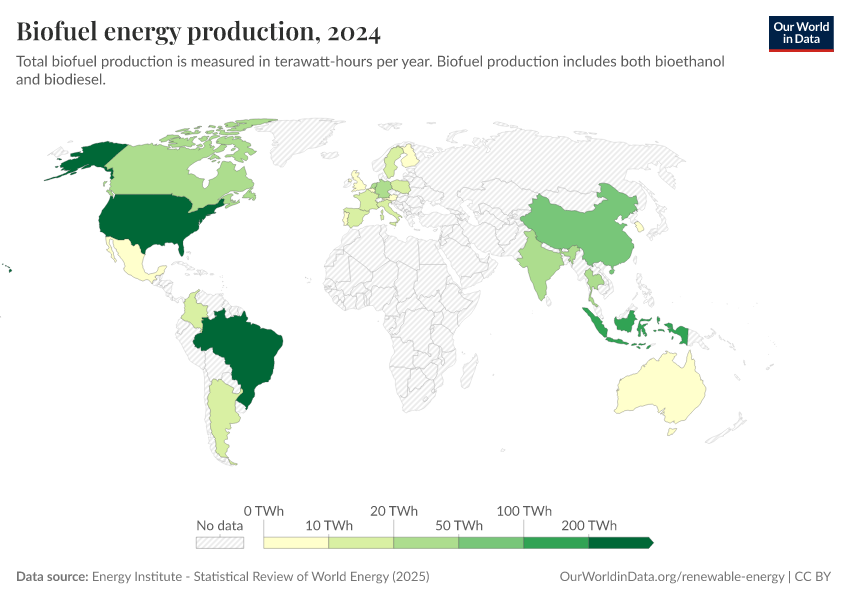

Some might imagine that biofuels have lost their relevance. But historical policies supporting them are still in place. As shown in the chart below, the world produces more biofuels than ever, and this trend is expected to continue. Global production is focused in a relatively small number of markets, with the United States, Brazil, and the European Union dominating. Since there are no signs of policies changing in these regions, we would not expect the rise of biofuels to end.

Most of the world’s biofuels come from sugarcane (mostly grown in Brazil), cereal crops such as corn (mostly grown in the United States and the European Union), and oil crops such as soybean and palm oil (which are grown in the US, Brazil, and Indonesia).

In the map below, you can get a view of where the world’s biofuels are grown.

Collectively, these biofuels produce around 4% of the world’s energy demand for transport. While that does push some oil from the energy mix, the climate benefits of biofuels are not always as clear as people might assume.

Once we consider the climate impact of growing the food and manufacturing the fuel, the carbon savings relative to petrol can be small for some crops.3 But more importantly, when the opportunity costs of the land used to grow those crops are taken into account, they might be worse for the climate.4 That’s because agricultural land use is not “free”. If we chose not to use it for agriculture, then it could be rewilded and reforested, which would sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

From a climate perspective, freeing up that cropland from biofuels would be one alternative. However, another option is to utilise it for another form of energy, which could offer a much greater climate benefit.

This should be easy to estimate. If you know how much land in the United States (or any other country) is used for corn, and what fraction of corn is for biofuels, you can calculate the amount of land used for biofuels.

What makes things complicated is that biofuels often produce co-products that are allocated to other uses, such as animal feed. Not all of the corn or soybeans turn into liquid that can be put in a car; some residues can then be fed to pigs and chickens. How you adjust this land used for biofuels and their co-products can lead to quite different results.

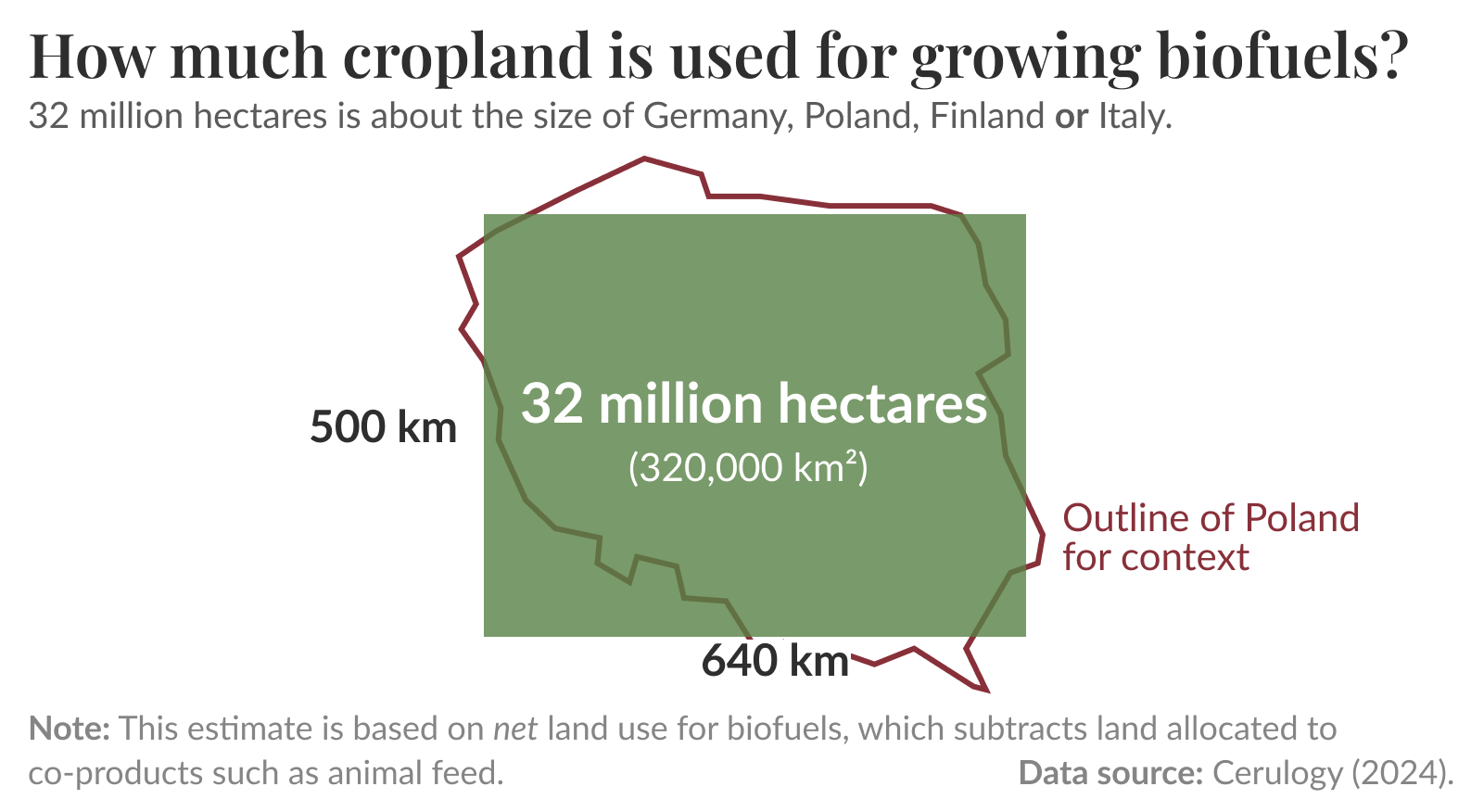

A recent analysis from researchers at Cerulogy estimated that biofuels are grown on 61 million hectares of land.5 But when they split this allocation between land for biofuels and land for animal feed, the land use for biofuels alone was 32 million hectares. The other 29 million hectares would be allocated for land use for animal feed.

There are much higher published figures. The Union for the Promotion of Oil and Protein Plants estimates that as much as 112 million hectares are “used to supply feedstock for biofuels”.6 By this definition, there is no adjustment for dual use of that land or the land use of co-products. That’s one of the reasons why the figures are much higher. Even taking this into account, the numbers are still higher, and the honest answer is that we don’t know why.

For this article, we’re going to assume a net land use of 32 million hectares. This is conservative, and that is deliberate. As we’ll soon see, the amount of solar power we could generate, or the number of electric vehicles we could power on this land, is extremely large. And that’s with us being fairly ungenerous about the amount of land available. Larger land use figures could also be credible; in that case, the potential would be even higher.

How large is 32 million hectares? Imagine an area like the one in the box below: 640 kilometers across, and 500 kilometers high. For context, that’s about the size of Germany, Poland, the Philippines, Finland, or Italy.

Could we use those 32 million hectares of land differently to produce even more energy than we currently get from biofuels?

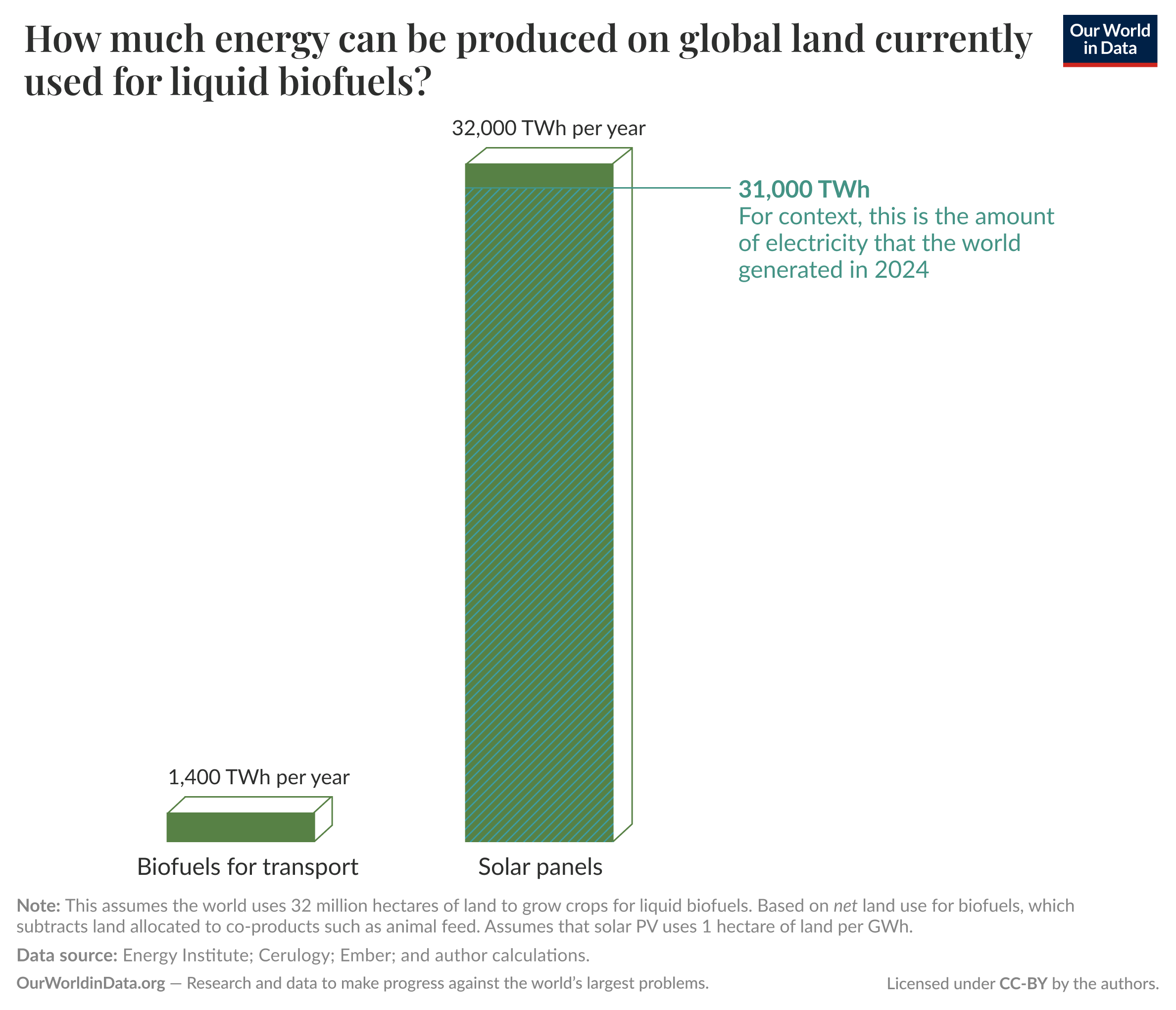

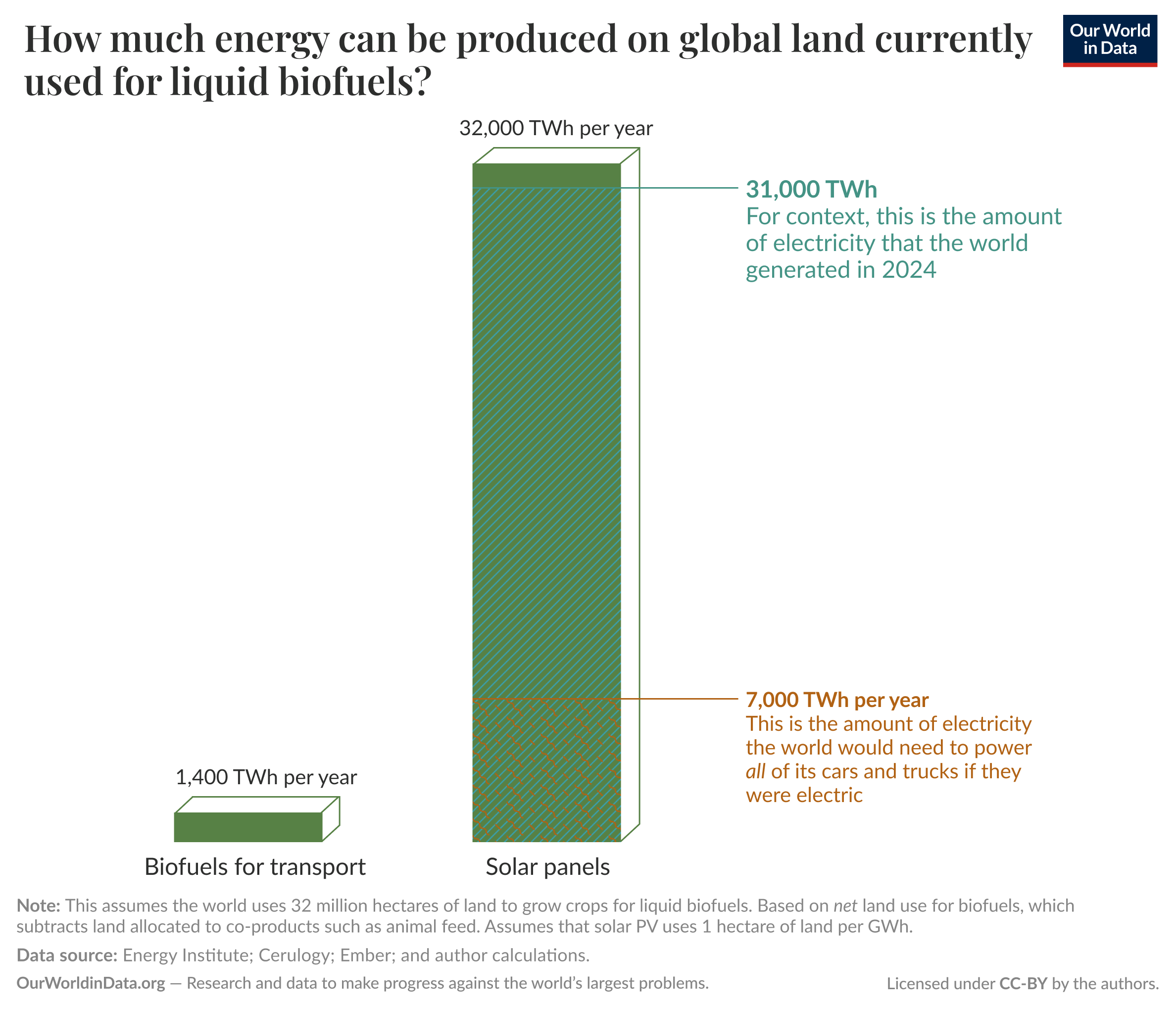

The answer is yes. If we put solar panels on that land, we could produce roughly 32,000 terawatt-hours of electricity each year.7 That’s 23 times more than the energy that is currently produced in the form of all liquid biofuels.8 You can see this comparison in the chart.

32,000 terawatt-hours is a big number. The world generated 31,000 TWh of electricity in 2024. So, these new solar panels would produce enough to meet the world’s current electricity demand.

Again, our proposal isn’t that we should cover all of this land in solar panels, or that it could easily power the world on its own. We don’t account for the fact that we’d need energy storage and other options to make sure that power is available where and when it’s needed (not just when the sun is shining). We’re just trying to get a sense of perspective for how much electricity could be produced by using that land in more efficient ways.

If we put solar panels on that land, we could produce roughly 32,000 terawatt-hours of electricity each year.

These comparisons might seem surprising at first. But they can be explained by the fact that growing crops is a very inefficient process. Plants convert less than 1% of sunlight into biomass through photosynthesis.9 Even more energy is then lost when we turn those plants into liquid fuels. Crops such as sugarcane tend to perform better than others, like maize or soybeans, but even they are still inefficient.

By comparison, solar panels convert 15% to 20% of sunlight into electricity, with some recent designs achieving as much as 25%.10 That means replacing crops with solar panels will generate a lot more energy.

Now, you might think that we’re comparing very different things here: energy from liquid biofuels meant to decarbonize transport, and solar, which could decarbonize electricity. But with the rise of affordable and high-quality electric vehicles, solar power can be a way to decarbonize transport, too.

Run the numbers, and we find that you could power all of the world’s cars and trucks on this solar energy if transport were electrified.

Of course, these vehicles would need to be electrified in the first place. This is happening — electric car sales are rising, and electric trucks are now starting to get some attention — but it will take time for most vehicles on the road to be electric. For now, we’ll imagine that they are.

We estimate that the total electricity needed to power all cars and trucks is around 7,000 TWh per year, comprising 3,500 TWh for cars and a similar amount for trucks. We’ve added this comparison to the chart.

You could power all of the world’s cars and trucks on this solar energy if transport were electrified.

That’s less than one-quarter of the 32,000 TWh that solar panels could produce on biofuel land. Consider those options. The world could meet 3% or 4% of transport demand with biofuels. Or it could meet all road transport demand on just one-quarter of that land. The other three-quarters could be used for other things, such as food production, biofuels for aviation, or it could be left alone to rewild.

It’s worth noting that in this scenario — unlike using solar for bulk electricity needs — we would need much less additional energy storage solutions, because every car and truck is essentially a big battery in itself.

The reason these comparisons are even more stark than biofuels versus solar is that most of the energy consumed in a petrol car is wasted; either as heat (if you put your hand over the bonnet, you will often notice that it’s extremely warm after driving) or from friction when braking. An electric car is much more efficient without a combustion engine, and thanks to regenerative braking (which uses braking energy to recharge the battery). That means that driving one mile in an electric car uses just one-third of the energy of driving one mile in a combustion engine car.

Put these two efficiencies together, and we find that you could drive 70 times as many miles in a solar-powered electric car as you could in one running on biofuels from the same amount of land.

Our point here is not that we should cover all of our biofuel land in solar panels. There are reasons why the comparisons above are simpler than the real world, and why dedicating all of that land to solar power would not be ideal.11

The world could meet 3% or 4% of transport demand with biofuels. Or it could meet all road transport demand on just one-quarter of that land.

What we do want to challenge is how we think and talk about land use. People rightly question the impact of solar or wind farms on landscapes, but rarely consider the land use of existing biofuel crops, which do very little to decarbonize our energy supplies. Whether we’ll run out of land for solar or wind is a common concern, but when we run the numbers, it’s clear that there is more than enough; we’re just using it for other things. Stacking up the comparative benefits of those other things allows us to make better choices, if they’re available.

In this article, we wanted to run the numbers and get some perspective on how we could use that Germany- or Poland-sized area of land in the most efficient way. What’s clear is that we could produce a huge amount of electricity from solar on just a fraction of that land. We could power an entire global electric car and truck fleet on just one-quarter of it.

Land use comes at a cost: for the climate, ecosystems, and other species we share the planet with. That means we should think carefully about how to use it well. That might mean a mix of biofuels for aviation, and solar power for road transport and electricity grids. It might mean going all-in on solar. Or it could mean using some of it for solar power, and leaving the rest alone. Sometimes, the most thoughtful option is not using land at all and letting it return to nature.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Max Roser and Edouard Mathieu for editorial feedback and comments on this article. We also thank Marwa Boukarim for help and support with the visualizations.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie and Pablo Rosado (2026) - “Putting solar panels on land used for biofuels would produce enough electricity for all cars and trucks to go electric” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260112-091056/biofuel-land-solar-electric-vehicles.html' [Online Resource] (archived on January 12, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-biofuel-land-solar-electric-vehicles,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Pablo Rosado},

title = {Putting solar panels on land used for biofuels would produce enough electricity for all cars and trucks to go electric},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2026},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260112-091056/biofuel-land-solar-electric-vehicles.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.