This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

Why are coalmines closing in Queensland?

Recent Queensland mine closures due to economic circumstances include QCoal’s Cook Colliery and BMA’s Saraji South. Burton mine owner Bowen Coking Coal remains in administration. Other recent closures (from FY2023-24) include the Bluff, Millenium and Wilkie Creek mines.

“These mines share one thing in common: they are all previously mothballed mines that were shut on the grounds of being uneconomic. So, it’s no surprise that after coal prices have declined to historical levels that they are uneconomic again. There are various factors that play into the economics equation, but the owning companies have deemed them uneconomic – now for the second time.” – Andrew Gorringe, IEEFA

Sold on to other mining, these companies mothballed mines were restarted in the hope of windfall profits when coal prices spiked. Now that coal prices have returned to historical levels, these mines have become uneconomic again.

Table: Mothballed mines now closed again

Sources: Qld government production data, GEM. Note: V/A = voluntary administration.

There are always exceptions, and Stanmore Resources is one such example. It purchased the mothballed Isaac Plains metallurgical coalmine in July 2015 for a nominal consideration of $1 (plus the rehabilitation liability), after the mine ceased operations in 2014. Stanmore has gone on from strength to strength, growing its portfolio of coalmines and returning solid profits. The success of this deal may have contributed to the optimism of acquisitive miners.

Cost Pressures

For some time, the coal industry has faced rising costs that remain stubbornly high, squeezing profit margins. A comparison of unit costs for metallurgical (met) coal producers operating in Queensland found that while prices have returned to historical levels, unit costs remain elevated. Company reports from 2018 to 2025 show unit costs rose by up to 50% for met coalminers. There are many contributing factors, including Queensland’s higher royalty rates, but these have risen by a lesser amount than other costs.

Cost inflation has been reported by miners for several years. During this time, miners have continually revised up unit cost outlooks, explaining away variances as temporary pressures. There is a symphony of factors affecting miners’ costs, from labour and fuel to higher distribution costs and coal royalties.

Many of these cost increases are far from temporary, and there is an increasing risk they will remain higher for longer.

“They’ve got a cost problem – and royalties are one of those elements – but they’re certainly not the main element. They’ve also been focused on getting volume at any cost. When the prices were good and they wanted to sell as much coal as they could, they expanded with little thought to costs.”

Is Queensland a good investment?

“It’s not that Queensland is not investible. It’s just that coalmines are not a good prospect right now. The major driver of the future viability of coalmines in Queensland is the price for the coal. It’s not sufficiently covering the cost to produce it.”

Queensland is home to Australia’s premium hard coking coal – the highest value coal used in steelmaking. The Bowen Basin stretches across 650km of central Queensland. It hosts 85% of the state’s coalmines, and produced 195 million tonnes of export met coal to global markets in FY2024-25.

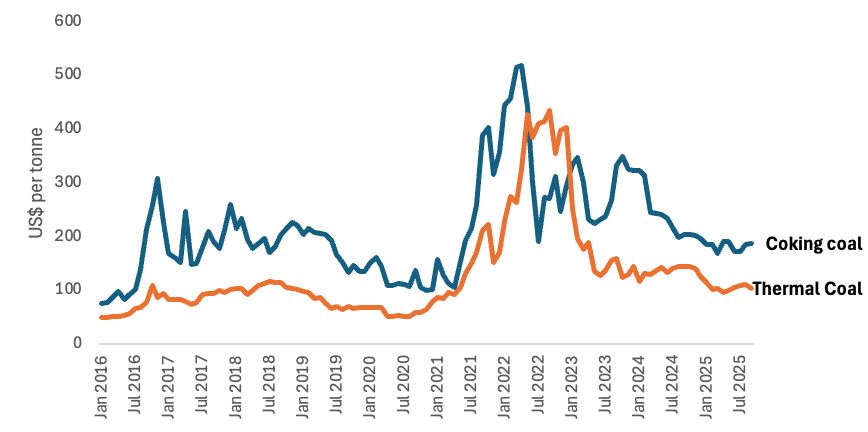

As such it is the epicentre for Australia’s met coal exports. The premium low-volatility hard coking coal (PLV HVV) coal price is the benchmark index. It tracked at US$182 per tonne for the first nine months of 2025, according to S&P Global. They project long-term forecasts for the coal price are that will be no greater in 2035, achieving US$181 per tonne.

Figure: Australian export coal price trend

Sources: S&P Global, IEEFA, Coking Coal: TSI Premium Hard Coking Coal Australia Export FOB East Coast Port, Thermal Coal: Coal ICE gC Newc.

The federal government forecasts Australia’s met coal export volumes. It has continually revised down its forecasts as steelmakers shift away from coal, and some Asian importers diversify coal supplies away from Australia.

What about the impact on regional jobs?

According to the Bowen Basin resource industry workforce, the local resources industry employed 44,000 workers in 2023; of these, 41,600 (95%) were in coalmining. They were split between contractors and coalmine employees.

Why are Queensland mines allowed to stay idle?

The Queensland government allows shuttered mines to remain dormant – in care and maintenance mode – indefinitely. Some other jurisdictions require mining companies to show cause why a mine should sit idle. In Queensland, a financial assurance scheme provides for final rehabilitation. It also enables mining to restart if market conditions improve.

“Governments might view opening new mines or restarting mothballed mines as a hope of preserving jobs for regional communities and royalties for the state budget. But, as the world transitions away from coal, coal companies are lining up to be the last man standing – in a race to the bottom.”

In a world with fewer coal producers, some miners may be positioning themselves to outlast competitors in a declining market. This can provide a competitive advantage, particularly for those who have secured long-term coalmining approvals.

Are royalties sending coalminers broke?

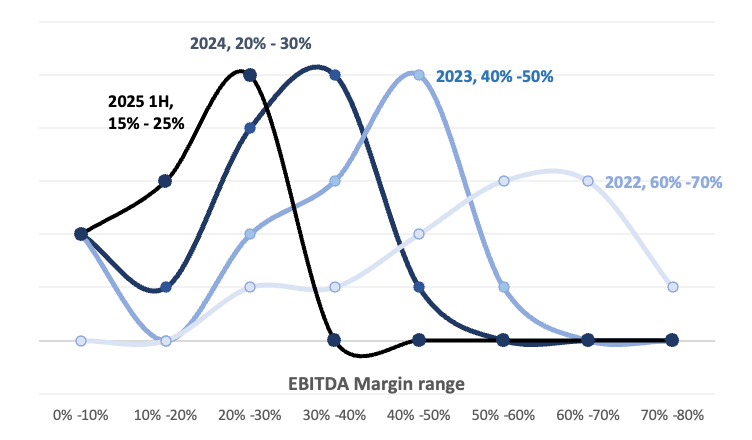

Underlying earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) is a measure of cashflow generated by coalminers – a proxy for asset profitability. EBITDA margins (EBITDA: sales revenue ratio) for coalminers have declined significantly over the past few years.

Sources: Company financial reports, IEEFA. Note: 2025 1H = the half-year reporting period to June 2025.

The margins of major coal companies remain strong by historical standards. In the June 2025 half-year, major coalminers reported margins of 15%-25%: BMA (11%), Stanmore (17%), Glencore’s steelmaking division (25%) and Whitehaven’s Queensland met coal assets 25%.

Private royalties – not government royalties – are sometimes used in the sale of coalmines. To negotiate a reduced price on a mine, a buyer may offer to pay the seller a trailing royalty on the value of coal sold from the mine. Miners are quite comfortable with paying additional royalties to reduce the upfront cost of buying a coalmine.

Recent Queensland mines sales that included private royalty provisions include:

- Bowen Coking Coal (BCC)’s acquisition of 10% of the Broadmeadow East Mine in 2023 and purchase of Bluff mine in 2021.

- Stanmore Resources’ sale of its Wards Well tenement in 2023, and 50% acquisition of the Eagle Downs project in 2024. The latter included a potential contingent private royalty payment depending on the coal price achieved.

- QCOAL’s acquisition of Cook Colliery in 2019 involved settling prior contingent private royalty payments – a carryover from the previous owner.

- Anglo American’s failed sale of its coalmine portfolio earlier this year contained a number of contingent payments – one from the Grosvenor mine’s restart, and a capped 35% revenue-sharing arrangement with the purchaser.

What are the threats to coalmines in Queensland?

Downward pressure on coal prices means the most marginal producers face increasing challenges to stay open. With some cost factors now embedded, as discussed earlier, additional factors are beginning to show their impact, including:

- Contractor labour costs, with results of the “same job, same pay” negotiations flowing through to reported results.

- Climate change impacts (such as continued and intensifying extreme weather events, floods and heatwaves).

- Rising mine deposit strip ratios as existing mining areas are depleted.

- Costs incurred for coalmine emissions under the federal government’s Safeguard Mechanism.

What are the balance sheet repercussions of mine closures?

Miners are required to assess the carrying value of their coalmines annually, and to adjust the reserves and potentially the carrying value of these assets if mining circumstances change considerably.

For example, after a fire suspended production at the Grosvenor mine in 2024, Anglo flagged in its 2024 interim results: “At Grosvenor, which has a book value of $1.3 billion, we will monitor the carrying value closely through the second half as we understand more about the impact of the fire on assets and overall planning for Moranbah-Grosvenor as well as the sales process.” After the Moranbah North mine experienced a similar incident, the sale process was derailed and up to 200 employees were retrenched.

Despite declining profitability and mine closures, Australian coalminers have not declared any recent impairments due to economic factors affecting the prospect of economic extraction.

BHP makes some curious assumptions in its coal reserves statements in its 2025 Annual Report. It uses price assumptions based on the historical three-year average (e.g., hard coking coal US$321.16 per tonne) whether or not there is a strong likelihood of these prices recurring.

While these assessments rely on a significant amount of management judgement, perhaps the closure of its Saraji South mine is sufficient evidence that BHP should update the carrying value of its coal assets.

“Now is probably a good time for Anglo and BHP to consider the carrying value of their coal assets.”

Miners hoping to start, restart or on-sell mothballed mines will find it more convenient to blame high government royalties than to declare them uneconomic.