- Scientists have proposed using anchored seabed curtains to block warm ocean water from accelerating ice loss at Antarctica’s rapidly melting Thwaites Glacier — a possible climate fix that falls into the realm of geoengineering.

- Thwaites is losing 50 billion metric tons of ice annually and could raise sea levels by more than 60 cm (2 ft) if it collapses.

- Critics warn that a handful of proposed geoengineering projects in the world’s polar regions distract from decarbonization efforts, while supporters argue some geoengineering may be a necessary last-resort measure as governments fail to address rising greenhouse gas emissions.

- The curtain project could cost up to $80 billion, scientists estimate, but may prevent trillions in climate-related damages.

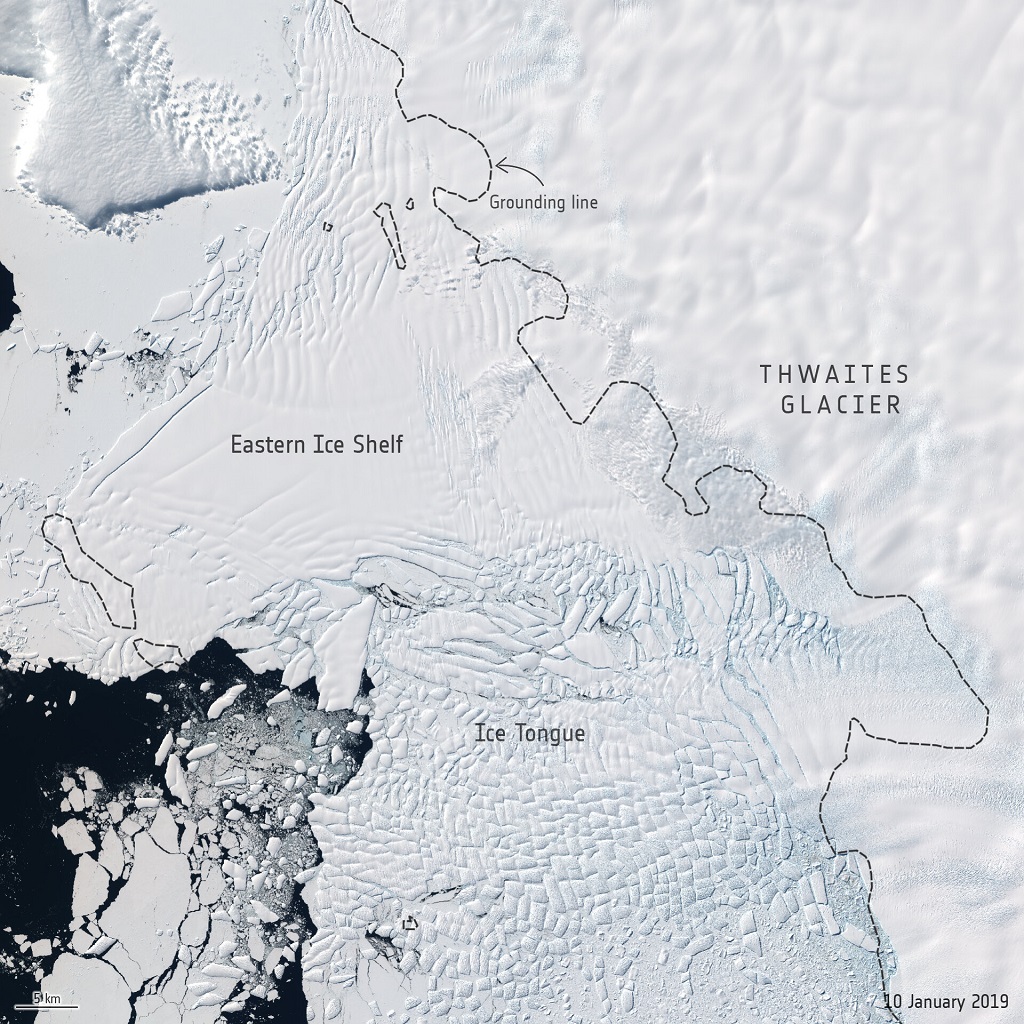

Thwaites Glacier rises above the Amundsen Sea in the Antarctic, a towering white cliff abutting cerulean waters. Roughly the size of Great Britain and spanning 120 kilometers (80 miles) across, Thwaites — part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet — may seem all but invincible. But among scientists, it’s known as the “Doomsday Glacier” for its potential to raise global sea levels.

Now, as greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, some polar researchers are investigating a radical geoengineering plan to install seabed curtains that could protect Thwaites from melting down.

Thwaites Glacier is rapidly shedding ice as the world warms from climate change, driven by the burning of fossil fuels. Thwaites is losing about 50 billion metric tons of ice every year, contributing to about 4% of present-day sea-level rise worldwide. But if Thwaites were to melt down entirely, it could raise the average global sea level by more than 0.6 meters (2 feet) over the next few centuries. This would inundate coastal cities around the world and force hundreds of millions of people to migrate.

Some scientists think it could be even worse. Thwaites may act as a natural dam for the rest of ice contained within West Antarctica. If it collapses, it could destabilize other glaciers, potentially pushing global sea level rise to as high as 3 m (10 ft).

In a 2024 briefing, the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a group of polar scientists closely studying the glacier’s fate, said a worst-case meltdown scenario can’t be ruled out, given that global greenhouse gas emissions are continuing to rise. Their findings suggest that Thwaites and much of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could be lost by the 23rd century.

The risks would be catastrophically high for humanity.

‘Not empty hope’

That’s why this January a group of scientists will travel to Thwaites to conduct field research on an idea once dismissed as outlandish: Building a giant sea curtain to shield Thwaites from the intrusion of warm water that threatens to be its undoing.

“To give people some potential solutions that might preserve the most vital parts of the [Earth] system, is proving real hope,” says John Moore, a glaciologist with the University of Lapland in Finland, who first proposed the idea. “And it’s not empty hope. We know that some of these things work in nature — if you keep away the warm water, ice sheets are stable.”

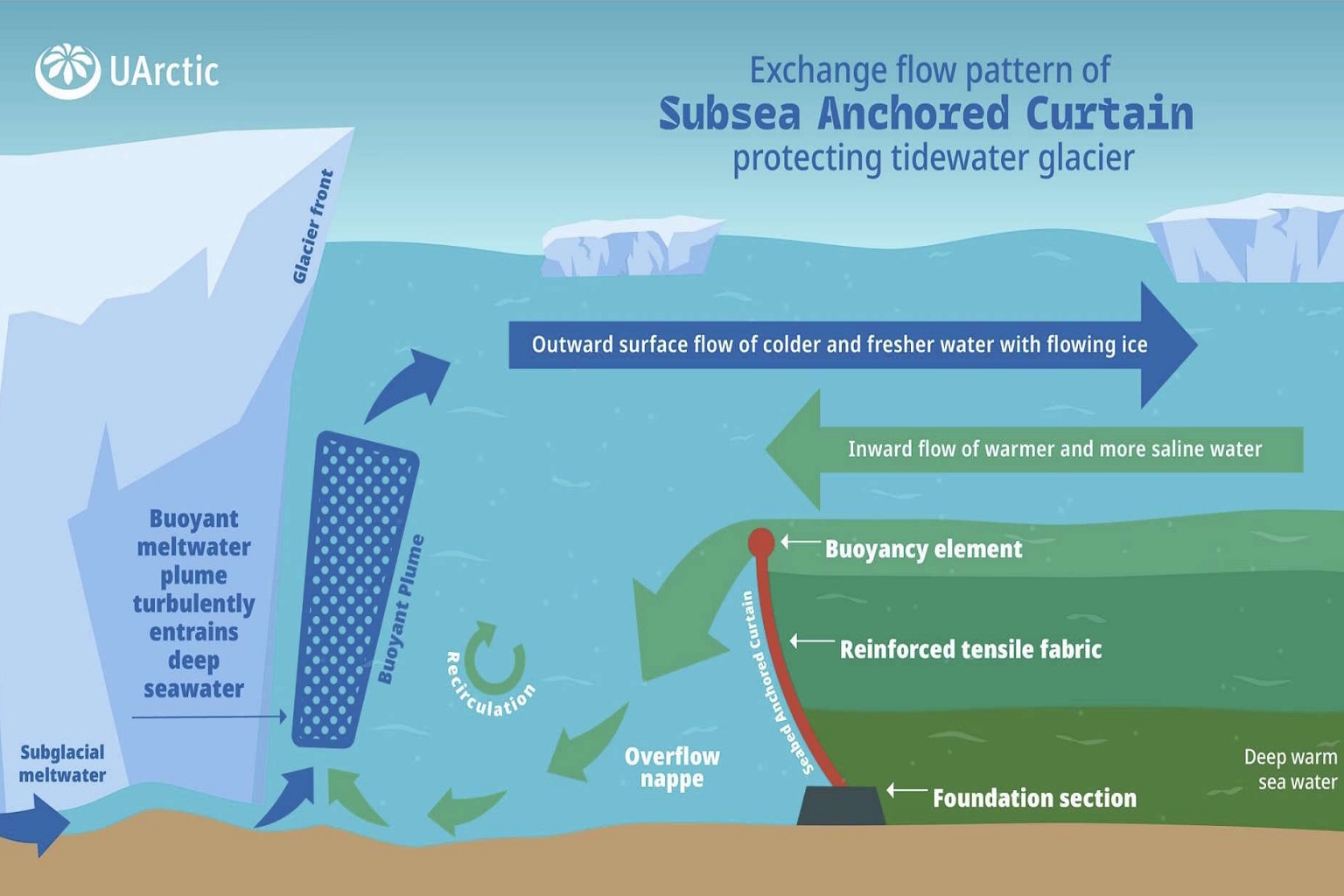

Warmer ocean water flowing underneath Thwaites is thought to be the driver of its massive ice loss, vigorously speeding up melting. In 2018, Moore and Michael Wolovick, a glaciologist with the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, put forward the idea of blocking the underwater pathways that deliver the warm water to the glacier. The mechanism they now propose would be a flexible, buoyant curtain anchored to the seabed.

With the world setting back-to-back warmest year records in 2023 and 2024, and global climate diplomacy talks falling apart, that idea has gained traction as Antarctica warms at twice the rate of the global average.

On the upcoming visit to Thwaites, scientists will deploy two underwater robots in the Pine Island Trough, the possible location for a sea curtain, to gather data to help them understand whether a curtain could be installed — and if it could be done fast enough to make a difference for Thwaites and the world.

“The robots will travel up and down wires and they will check on the water speed, water temperature, water salt,” says climate scientist David Holland with New York University, who is also working on the project.

The assignment will last two years, after which point, “we can then say to an engineer, this is the amount of force — this is how fast this thing is going,” Holland says.

The Seabed Curtain Project is supported by the University of the Arctic, a cooperative network of nearly 200 universities and research institutions. The project has obtained funding from the Tom Wilhelmsen Foundation, the charitable arm of Norwegian shipping giant Wilhelmsen, and Outlier Projects, a philanthropic organization created by former Meta chief technology officer, Mike Schroepefer, which gives grants to research groups working on climate tech interventions.

The project is among a handful of proposals that scientists have put forward in a last-ditch effort to preserve the rapidly melting polar regions. These include drilling holes to the glacier bed to drain the water that lubricates the glacier’s outward flow, and refreezing Arctic sea ice by pumping up water from below onto the ice. One study also found solar geoengineering, known as stratospheric aerosol injection, might be able to save the West Antarctic Sheet.

However, these projects, which fall into the realm of geoengineering, have received fierce pushback from some polar scientists. This month, 42 polar scientists — from institutions such as the British Antarctic Survey, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and International Cryosphere Climate Initiative — published an assessment of five polar geoengineering projects currently in development in the journal Frontiers in Science, titled “Safeguarding the polar regions from dangerous geoengineering.”

The scientists concluded that the proposed geoengineering projects would cost billions of dollars in setup and maintenance, and argued they would reduce pressure on policymakers and industries to slash greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, the assessment looked at the ecological, legal and political obstacles in advancing these ideas.

Those in favor of considering such interventions argue that the world desperately needs a Plan B. Global carbon emissions from fossil fuels continue to hit record highs, despite promises from world leaders to address climate change. Moreover, scientists say a certain amount of sea level rise from Thwaites is already locked in, even if the world were to stop all emissions tomorrow. And some studies suggest at least a partial loss is now unstoppable.

Holland, too, says his views have changed in recent years. He’s made eight trips to Thwaites and once thought the seabed curtain was a crazy idea. “Can you put in a curtain and save the coastline of the world? I would have said, ‘No way,’ two years ago.”

But now, he says it’s doable — at least from a scientific perspective.

“At some point, you just have to ask, ‘Is it plausible?’ Because if you’re against it, then what are you against? Some unforeseen consequence that’s going to destroy the Earth? Well, maybe that’s what’s happening right now.”

How an Antarctic curtain could work

One of the reasons scientists think an Antarctic curtain could work is because the warm, dense bottom waters melting Thwaites are first funneled through narrow channels in the continental shelf. That pathway, they theorize, could be plugged. Moore and Wolovick’s initial design focused on installing an artificial sill up to 100 m (330 ft) high to block the warm water reaching Thwaites.

“You take advantage of nature’s chokepoints to increase that with a barrier,” Moore says.

Over the past seven years, their blueprint has evolved. “Originally, we had very naive concepts as scientists and not engineers that you would essentially build some kind of gravel dam to block this,” Moore says.

In a 2023 paper in the journal PNAS Nexus, the glaciologists instead proposed installing flexible curtains across 80 km (50 mi) at depths of 600 m (2,000 ft) on alluvial sediment. Curtains, they realized, would be cheaper, withstand iceberg collisions, and be easier to repair or remove in the face of unintended consequences, unlike a permanent fixture. Such an intervention, they calculated, would cost between $40 billion and $80 billion to install, and an additional $1 billion to $2 billion in annual maintenance.

While that might sound steep, it’s nothing compared to the economic damages wrought by sea level rise, which scientists estimate could reach into the trillions of dollars per year by the end of this century.

“It’s a no-brainer to think, ‘Do we spend $10 million finding out if this works? Or do we lose $10 trillion for doing nothing?’” Moore says.

In temperate waters, existing offshore and deep ocean construction techniques would make installing such a curtain possible. Polar waters, however, present a greater challenge, given the harsh environment and brief working seasons. But Moore and Wolovick say this could be overcome with present-day technology.

But other scientists disagree.

Dangerous territory

In the new paper published in Frontiers in Science, the authors closely examine the proposed seabed curtain.

“We were seeing some of these geoengineering ideas being presented at prominent meetings like the United Nations climate COP meetings or the World Economic Forum, and being done in such a way that minimizes the environmental challenges and maximizes the advantages,” says lead author Martin Siegert, a glaciologist at the University of Exeter in the U.K.

That, he says, compelled other polar scientists to critically examine the projects being discussed.

“If there is a sense of a solution other than decarbonizing, for some people, that will be appealing,” Siegert says. “We think that’s a really dangerous message to be sending at this moment, when we absolutely need to nail down decarbonizing and do it really quickly.”

First, their scientific assessment considers whether it would be feasible to install curtains that could withstand the force and hazards of the Antarctic region.

The proposed deployment site is considered “one of the harshest environments on Earth, with a transit time of over one week from the nearest port and access likely to be possible only for a few months each year owing to polar darkness and extreme ice and climate conditions,” the researchers write, adding the Inner Bay site has only been accessed once in the last 40 years.

The study also notes that even if successful, such an intervention could have unintended consequences of rerouting warm water to other ice shelf systems, as well as creating a barrier to marine life in the Amundsen Sea.

The politics are also tricky, as the approval and governance of a sea curtain would fall under the Antarctic Treaty System, a network of 57 nations that work to ensure Antarctica is only used for peaceful, scientific purposes and preserved as a global common.

“Obtaining international consensus to intervene in Antarctic processes at such a huge scale has never been attempted before, and those advocating sea curtains have given this necessary item scant consideration thus far,” the study reads.

Scientists also took issue with the proposed costs, arguing $80 billion was a dramatic undercount of the money it would take to complete such an intervention, considering the costs of other engineering megaprojects, such as China’s Three Gorges Dam.

“If we’re going to spend hundreds of millions or maybe even billions of dollars on some of these ideas, it’s better spent on decarbonizing,” Siegert says.

Next steps

So far, governments and industry have failed to make the deep cuts necessary to tamp down planet-warming emissions, giving scientists little choice but to explore alternative methods to preserve the world’s polar regions, Moore says.

Looking at history, he says, he feels undeterred. “In the First World War, Britain built anti-submarine nets — curtains, if you like — around most of its coast, spanning thousands of kilometers,” he says. “That was a massive investment at the time, but it was an existential threat, so it had to be done.”

Moore and his colleagues say they hope to spend the next couple of years collecting data in the Amundsen Sea. This would serve as the scientific basis for the curtain’s design and potential deployment.

In 2027, they say they hope to test a curtain at Ramfjorden near Tromsø, Norway. But first they need to raise the funds — a key goal of the project at New York Climate Week this month, Moore says.

“We are very much in the research program,” he says. “Of course, we have the longer-term hope that eventually, if everything works out, we would be able to deploy this before it’s too late in Antarctica.”

That, he adds, is the big question. It’s possible that a deployment in 20 years’ time could already be past the point of no return for the glacier. But scientists won’t know until they do the work.

Arguments for rapid decarbonization, Moore says, ignore the fact that the human race has so far chosen not to do the “good option” of dramatically slashing carbon emissions.

“So what else is on the table? You’ve got bad, and you’ve got worse. We don’t know which is bad and which is worse between geoengineering, and, in a way, sitting on our asses and doing nothing — which is what we have done for the last 30 years.”

Banner image: Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica. Image by NASA via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Citations:

Goddard, P. B., Kravitz, B., MacMartin, D. G., Visioni, D., Bednarz, E. M., & Lee, W. R. (2023). Stratospheric aerosol injection can reduce risks to Antarctic ice loss depending on injection location and amount. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 128, e2023JD039434. doi:10.1029/2023JD039434

Jevrejeva, S., Jackson, L. P., Grinsted, A., Lincke, D., & Marzeion, B. (2018). Flood damage costs under sea‑level rise with warming of 1.5°C and 2°C. Environmental Research Letters, 13(7), 074014. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aacc76

Keefer, B., Wolovick, M., & Moore, J. C. (2023). Feasibility of ice sheet conservation using seabed anchored curtains. PNAS Nexus, 2(3). doi:10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad053

Moore, J. C., Macias-Fauria, M., & Wolovick, M. (2025). A new paradigm from the Arctic. Frontiers in Science, 3, 1657323. doi:10.3389/fsci.2025.1657323

Rignot, E., Ciracì, E., Scheuchl, B., & Dow, C. (2024). Widespread seawater intrusions beneath the grounded ice of Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(22), e2404766121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2404766121

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J., Morlighem, M., Seroussi, H., & Scheuchl, B. (2014). Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(10), 3502-3509. doi:10.1002/2014GL060140

Siegert, M., Sevestre, H., Bentley, M. J., Brigham-Grette, J., Burgess, H., Buzzard, S., … Truffer, M. (2025). Safeguarding the polar regions from dangerous geoengineering: A critical assessment of proposed concepts and future prospects. Frontiers in Science, 3, 1527393. doi:10.3389/fsci.2025.1527393

Van den Akker, T., Lipscomb, W. H., Leguy, G. R., Bernales, J., Berends, C. J., Van de Berg, W. J., & Van de Wal, R. S. W. (2025). Present‑day mass loss rates are a precursor for West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse. The Cryosphere, 19(1), 283-301. doi:10.5194/tc-19-283-2025

Wolovick, M. J., & Moore, J. C. (2018). Stopping the flood: Could we use targeted geoengineering to mitigate sea level rise? The Cryosphere, 12(9), 2955-2967. doi:10.5194/tc-12-2955-2018